Leaving behind Ruth Veranna and the other Goddards ….. Adeline takes us back and “we return up Burr Lane until we come to High Street”.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

The tenants of High Street

A mystery Harrison.

“The first house on the East side was occupied by Mrs. Harrison. She was a widow with one child. I believe Mr. Harrison was killed on the railway”

Mystery alert! Who is Mrs Harrison?

There is mention in the local press of ‘widow of Joseph Harrison’ who was living in Severn’s Yard in 1855.

Was Adeline confusing ‘Mr. Harrison’ with ‘Mr Wheatley’ ? …. see below

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

William not Charles Sudbury.

“The second house was in the occupation of Mr. Charles Sudbury, machinist at Ball’s” … a mistake by Adeline ?

Charles Sudbury was the glove manufacturing son of Francis and Ann (nee Mather) and brother of Ilkeston’s first Mayor, Francis junior. However his family lived in South Street.

Charles’s cousin was lacemaker William Sudbury, the eldest son of lacemaker Thomas and Mary (nee Goddard).

And he was the High Street Sudbury referred to by Adeline, spending most of his life in that street.

William’s mother was the oldest child of High Street framework knitter Jonathan Goddard and Kitty (nee Daykin) and thus the sister of John Goddard of Ilkeston Brass Band fame.

William’s father Thomas Sudbury was ‘an old and respected inhabitant’ of the town who committed suicide.

He left his High Street home one Tuesday evening in March 1859, saying he was going to work in his garden but walked towards Cossall. He came to a signal box on the Erewash Valley railway line and there hanged himself.

It was reported that “his features were not in the slightest degree distorted, but bore the impression of death under the most favorable circumstances”.

The Nottinghamshire Guardian suggested a motive for “so rash an act”; “the deceased has suffered many trade misfortunes lately”.

Shortly after this, in 1860, William’s mother Mary left High Street to live in Granby Street where she was joined by her youngest child Maria and her ‘chap’, lacemaker Thomas White, whom Maria married on July 15th 1861.

Born on January 25 1818, William Sudbury (senior) had married Lydia Brown, eldest child of Burr Lane lacemaker John Rawdin Brown and Sarah (nee Beardsley) on August 17th 1841.

The children of William and Lydia Sudbury

Together William and Lydia had at least seven children, several of whom are identified by Adeline.

Adeline counts that “there were three daughters, Sally, Mary Ann and Betsy. The son William left Ilkeston when a young man.”

— Sally was a dressmaker, remained unmarried and lived out the century with her parents at 2 High Street.

She died at 8 Lawn Terrace, Pimlico, on March 1st 1929, aged 86…. exactly 70 years after her paternal grandfather’s suicide.

— William junior married Elizabeth Crampton Rowe, daughter of Nottingham printer and newsagent Joseph and Harriet, in March 1873 but she died a few months later, after the birth of their daughter Elizabeth Ada.

A year later William married Elizabeth Hazeldine, daughter of Nottingham lacemaker George and Ann (nee Kerry) while his own daughter Elizabeth Ada Sudbury came to live with her grandparents in High Street.

And it was there that Elizabeth Ada stayed, giving birth to her illegitimate son Bernard in December 1896 at 1 High Street, before marrying warp hand John Oliver Warren the following year. They made their home at number 4.

— John Thomas alias Thomas married Mary Gaffney in 1877. The latter was born in Sligo, Ireland and with her parents Edward and Margaret came to Ilkeston in the 1850’s where the father worked as an ironstone labourer.

By the time of her marriage Mary had three illegitimate sons who took the Sudbury name after their mother’s marriage.

The youngest of these was Thomas, born March 14th 1876, and who found himself in a spot of bother in December 1887.

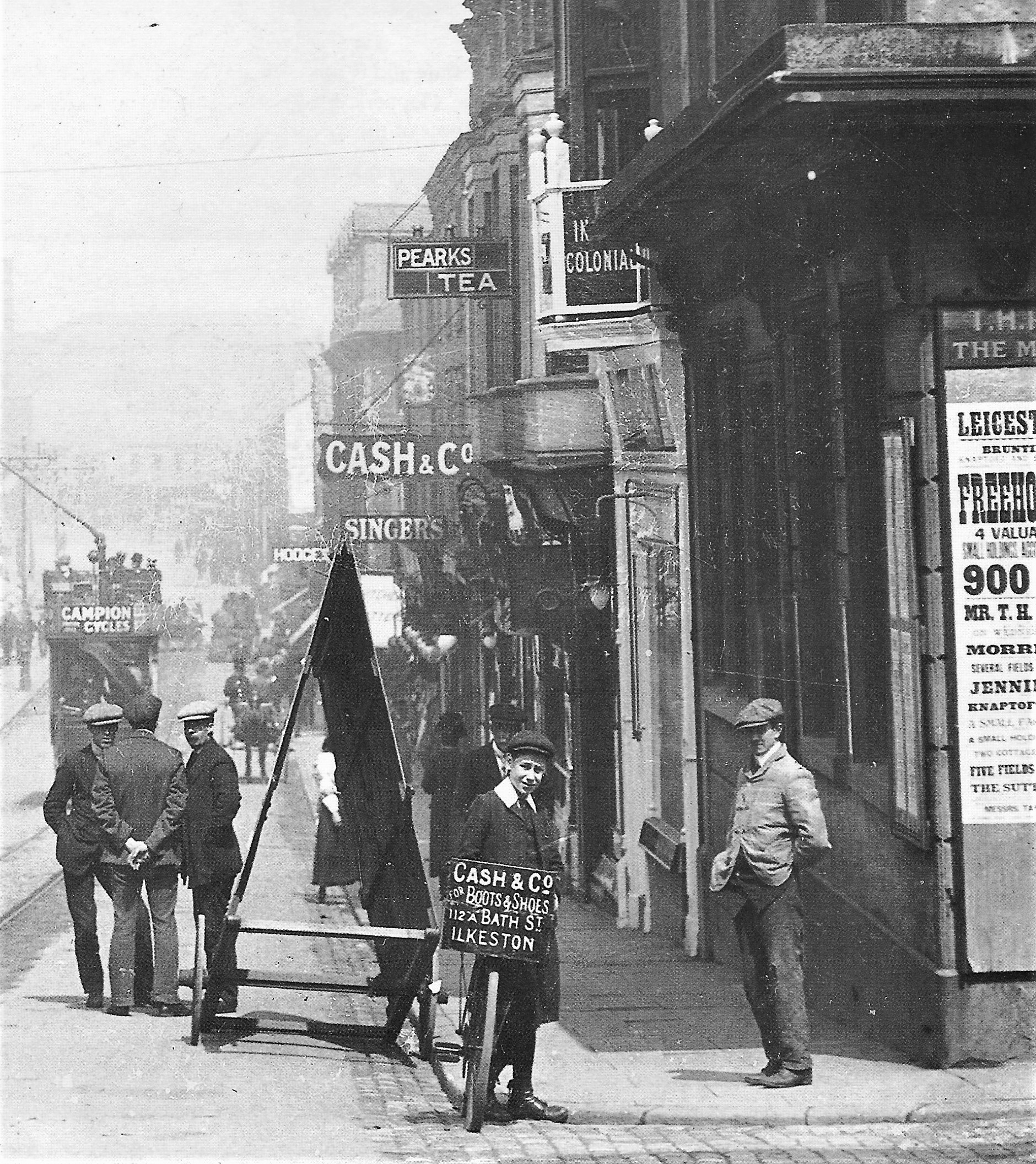

With his mate, 12-year-old George William Atkin (* see below), Thomas had been caught stealing a blue cloth waistcoat, worth 8½d, from the shop front of Cash Clothing Company in Bath Street (just below the Brunswick Hotel).

The two lads were both ordered to receive four strokes of the birch, the magistrate passing a flippant remark as he passed sentence — I dare say the two lads didn’t find it amusing. Nor did Thomas find it educational.

One year later Walter Wilkinson, a pork butcher of Nottingham Road, had sent 54 of his pork pies to the bakehouse to be finished off — only 53 returned, The missing one had been intercepted by young Thomas and thereafter ‘disappeared’. At the same time he also stole a pair of boots from a shop in Bath Street.

For both offences Thomas found himself in prison for a month and then on to a Reformatory until he was 16 years of age.

At the end of the century the family was living at 7 Tutin Street where both parents died.

— Mary Ann left her High Street home when she married John Fretwell, coalminer of Shipley, in November 1881, and moved into Burr Lane.

John Fretwell was the son of Shipley coalminer Abraham and Hannah (nee Davis)

At the end of the century Mary Ann and her husband were at number 63 Burr Lane.

— Like her oldest sister Sally, Betsy lived with her parents at 2 High Street. After their death she stayed there with Sally and brother Alfred.

At the age of 19 she gave birth to Henry Francis Sudbury who was both born and died in 1870.

Betsy remained a spinster and died at 63 Burr Lane on October 12th 1931, aged 80.

— Joseph died, aged 3, on February 26th 1856.

— Youngest child Alfred also remained unmarried, lived at 2 High Street and spent his last years with his unmarried sisters.

He died at 8 Lawn Terrace on June 2nd 1922, aged 63.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

One of William senior’s younger sisters was Mary Ann Sudbury and she ‘lost’ her husband, like her father, as he walked towards Cossall.

In December 1852 she had married Cossall-born Samuel Wheatley who in 1881 was working as a platelayer on the Midland Railway. He was also a cottager at his home in Cossall, described as in ‘comfortable circumstances’, keeping a cow or two.

One dark and foggy Saturday evening, January 1881, he left the Bridge Inn on Awsworth Road to walk the quarter of a mile to his home, necessitating a journey over the railway line and the Erewash Canal. He failed to complete the walk.

Dragging operations in the canal found his body several days later, and he was adjudged to have ‘accidentally drowned’.

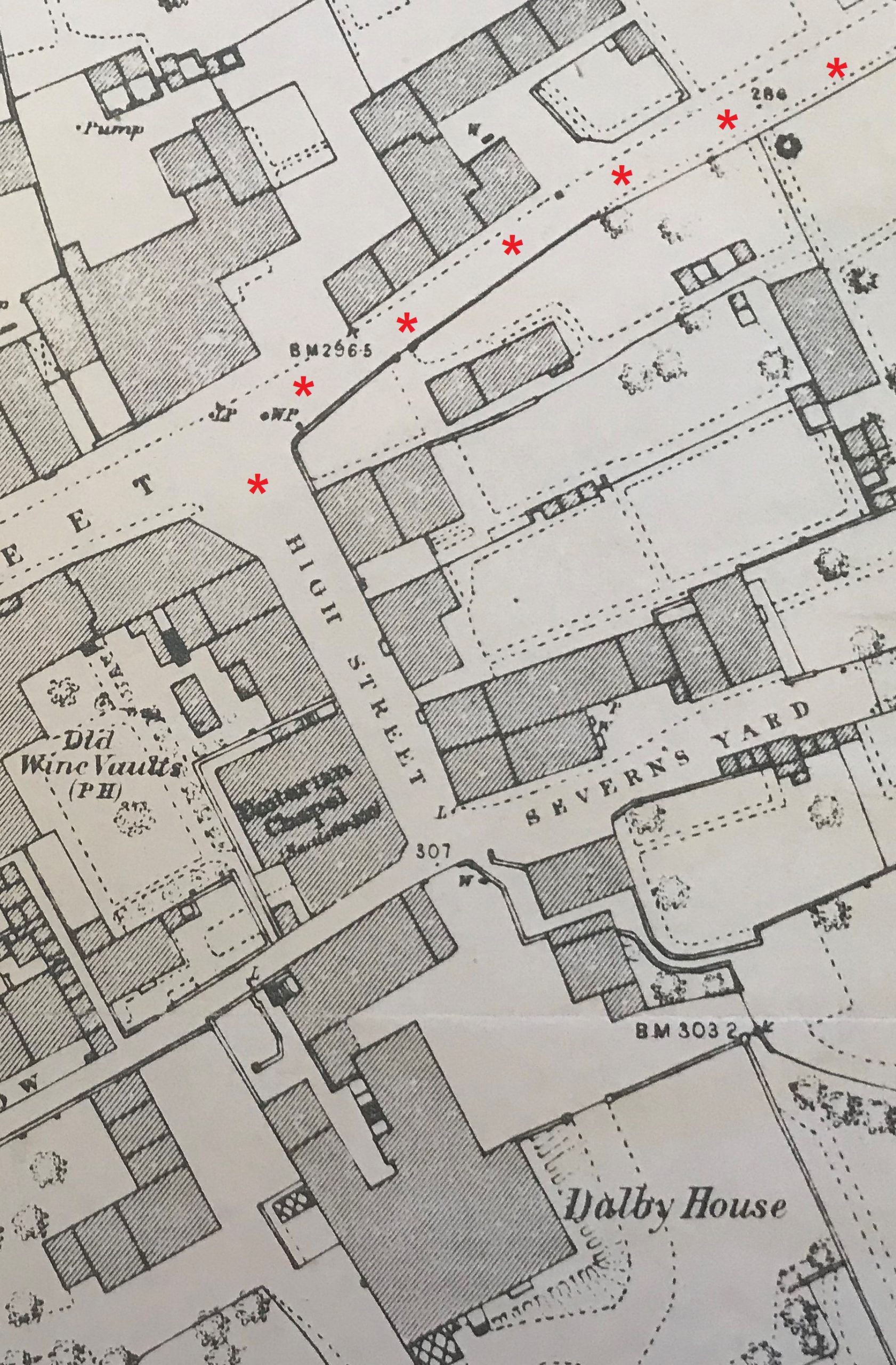

We are still in High Street, walking towards Severn’s Yard.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

We continue along High Street and in the other cottages leading to Mrs. Lee’s garden, lived ….

Anchor Carrier,

Anchor Carrier of High Street was probably the son of lacemaker William and Martha (nee Robinson, daughter of Thomas Robinson and Sarah (nee Taylor)) and thus the grandson of Anchor Carrier and Betty (nee George).

He was born in 1848 and had several siblings before his mother died in June 1851. His father then lived in High Street with a widow, Charlotte Blyth (nee Matthews), daughter of Thomas and Elizabeth (nee Harrison). Charlotte took the Carrier family name although she and William were not married and the couple had at least three children before William died in 1870 (I believe)

The children of both William’s unions then dispersed throughout Ilkeston to live with various relatives, employers or as lodgers while Charlotte went to live in North Street, reverting to her previous name.

Anchor found several lodgings in the Bath Street area before he died in December 1890 at 18 East Street.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

and also a Goddard family

Adeline’s ‘Goddards’ may have been the family of Samuel who lived at the confluence of High Street and Burr Lane. He was a framework knitter, the son of Jonathon, framework knitter, and Kitty (nee Daykin).

The 1841 census shows him living at High Street with Ann Smith by which time the couple already had had at least four children, all of them dying in infancy.

In July of that year son James Smith alias Goddard was born — he was to have a longer life which was to end tragically.

In April 1853 young James was working as an ironstone-getter for the Butterley Company at Ilkeston, and, with others, had gone down the mine to work for the night. A few hours into their work, a fire broke out down the pit, causing an explosion which blew out all the lights and dislodged two wooden planks, covering a pit of water.

Sulphur had previously been reported in the underground workings and it appeared that one of the workers was examining the mine with a lighted candle, without any guard and this was the cause of the explosion. Sfaety lamps had not been available at that time, for the workers.

James was trying to make his way out of the mine in the darkness when he fell into the water and was drowned.

A subsequent inquest a verdict of ‘Accidentally drowned’ was recorded, while the jury recommended that safety lamps should immediately be procured for the men working in the pit.

After the birth of James they had at least eight more children, most of them living beyond infancy although several of them died in adolescence. Their last child was Samuel, born in November 1858 – the day after his father’s death, on November 17th, in East Street, aged 47.

The children were initially ‘Smiths’ but later became ‘Goddards’ and the 1861 census shows ‘Ann Goddard, widow’ at Burr Lane although there is no (?) evidence — that I have yet discovered — that she ever married Samuel.

A month after Samuel’s death, Ann took the five youngest children — Maria, Elizabeth, George, Martha and Samuel — to be baptised at St. Mary’s Church. All were baptised as ‘Smith’. However Ann continued to be a ‘Goddard’ and she died in Burr Lane with that name on October 19th 1882.

She was buried at Stanton Road Cemetery as ’Ann Goddard’ on October 22nd.

Puzzle alert! Who were Ann Smith’s parents? She was born at Shipley, about 1818 and had a sister Sarah.

Why did Samuel and Ann not marry? Or did they?

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

and some Wheatleys

Born at Cossall, Nottinghamshire, in 1815, Charles Wheatley was the youngest son of framework knitter Mark and Sally (nee Wallner) and moved from Cossall after his marriage to Ann Hurst, daughter of agricultural labourer John and Mary (nee Rigley) of Kensington in November 1843.

He traded as a shoemaker in Kensington before appearing at Severn’s Yard off High Street as a coalminer in the 1871 census. There were at least eleven children born in the family and these are probably the ‘Wheatleys’ referred to by Adeline.

After the death of his wife Ann at Severn’s Yard on May18th, 1877, Charles was living with his daughter Jane, her husband, Elijah Rigley, and their ten children at several addresses in the Station Road area, until he entered the Cossall Almshouses in later life.

On Tuesday, June 19th 1892 Charles was visiting his daughter Jane at her home at 42 King Street, and left at about 8.30pm to walk back to Cossall via Ilkeston Junction, a route that he travelled regularly and knew well. He reached the railway lines at the Junction, went through a small gate and started to cross the three lines there, apparently with head down. At that moment the 8.20 passenger train from Nottingham was approaching the station. Walter Walker of 5 Taylor Street, gateman at this level crossing, saw all these events, saw that the train was about to hit Charles, whom he knew well and shouted to him to stop. Perhaps in the heat of the moment he forgot that Charles was very deaf and so took no notice of his cry. The train hit the old man and he was killed instantly.

At the inquest on the following Thursday afternoon at the Middleton Hotel in Station Road, there was talk of a installing a warning red light for passengers at the station, of locking the gates when trains were approaching and of building a footbridge over the lines. The jury returned a verdict of ‘Accidental death’, with recommendations that the public should be better protected at this crossing.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

and Spencers.

The ‘Spencers’ were lacemaker Amos, youngest child of Benjamin and Ann (nee Harrison) ; his wife Ann, formerly Ann Hives Chadwick, daughter of Charles and Mary (nee Hives), whom Amos married on August 3rd 1852 ; and ten of their 12 children — their first two children died in infancy.

Amos died at 5 Severn’s Yard (or 5 High Street) in April 1893, aged 61.

Ann died at the home of her daughter Agnes Emma, at 22 Hobson’s Drive in May 1902, aged 67.

Cottages in Severn’s Yard (now where Ilkeston Shopmobility Centre stands, 2021) ..courtesy of Jim Beardsley

—————————————————————————————————————————————

Postscript .. the ten year offending spree of George William Atkin

Let’s now return to George William Adkin or Atkin, young Thomas Sudbury’s partner in crime who was mentioned above*

By August 1893 George William Adkin was 19 years old but still less than five feet tall, had been convicted of five or six felonies and had served several terms in prison with hard labour. (He had just been released from six months in jail at Barnacre-with-Bonds, Lancashire, for housebreaking at Preston). However in this month it was his dad James who was in court, charged with assaulting his wife, and George William’s mother, Jane. The latter now had had enough and wanted a judicial separation, on the ground of cruelty. “Both went out drinking and drink was at the bottom of it ” declared a neighbour. The police were sure that their other son, Allen, would turn out ‘to be as bad as his brother’. However the parents were given a couple of months by the court to sort out their ‘differences’.

By November 1893 it was ‘the diminutive little chap‘ George William’s turn again !! In October he had stolen a pair of shoes from the shop of Samuel Smith (boot manufacturer) in Bath Street, and at Derby Winter Assizes got three months with hard labour. The judge warned him that if he continued along this path he would soon be sent away into penal servitude. (And the judge was right — although it took four more years to come true — by which time George William was 5′ 6” tall !!!)

In the meantime George William’s ‘rap sheet’ lengthened. In April 1894 he decided to set fire to a haystack belonging to Francis Sudbury, subsequently pleaded guilty and was sentenced to six months in jail, with hard labour. Then in January 1895 he was charged with stealing and then selling a tame rabbit, and with stealing a boy’s overcoat. As he pleaded guilty he was sentenced to three month’s imprisonment for each offence, but the sentences to run concurrently.

And George just couldn’t keep out of trouble. In October 1895 he thought he would try his luck on the Midland Railway. He was travelling from Sheffield to Beeston and ‘forgot’ to buy a ticket for the journey; when collared at his destination, George said that he was trying to get to Ilkeston !! Of course, this didn’t explain why he didn’t have a ticket or any money on him. He couldn’t pay his fine of one guinea and so took the alternative of a month in prison.

And then, in November 1895, another ‘lapse’ landed George William in court once more, to feature at the Derby Winter Assizes in February 1896. He was accused of taking a joint of mutton from a slab at the front of butcher William Twells’s Bath Street shop (close to Mount Street). Once more his ‘bad character’ was itemised, as were his past punishments — his flogging at the age of 12, his ‘reformatory years’ from 1889, six months in jail for housebreaking in 1893, six months for stealing boots also in 1893, six months for arson in July 1894, three months for larceny in January 1895, and in July of the same year two months for stealing boots — not to mention six occasions when he had appeared before magistrates for vagrancy !! Having only just recovered from an attack of typhoid fever George William was sentenced to only three months but with hard labour for this offence.

And then, in August 1896, George William had been caught once more with travelling without a ticket on the Midland Railway … and at Ilkeston Petty Sessions claimed that he had travelled between Nottingham and Yorkshire on seven occasions and had only been caught twice.

On being asked whether he was guilty or not guilty to this particular offence, he replied “neither” and shouted to reporters “Don’t put me in the paper — I don’t want my character spoiling!” At the conclusion of the hearing he asked for a sentence of six months; when he was awarded only a fine of 20s or a month in jail, George William fought and struggled so much that it took several constables to get him out of court.

On Sunday morning, September 19th 1897, P.Cs Robinson and Sisson were on patrol in Ilkeston Market Place when George William sauntered up to them and quietly confessed to setting fire to three stacks of hay — one at Little Hallam and two at Stanton Gate. He then took the pair of P.Cs to Little Hallam where he displayed his handiwork. A stack belonging to coal dealer brothers, John and Thomas West, was merrily burning away. Later, another stack belonging to Edward Severn was discovered, similarly destroyed, at Stanton Gate. George William was then incarcerated and on the day before his appearance at Ilkeston Police Court, he was visited in his cell by a local chaplain; their following conversation was later recounted in court, punctuated by laughter.

Chaplain: Well, George, I’m very sorry to see you in this state.

George: Are you really ?

Chaplain: I am. It’s not your fault.

George: Whose fault is it then ?

Chaplain: You ought to know who is leading you into temptation like this.

George: Who is it ?

Chaplain: It’s the devil called Satan, up above.

George: Then go and tell the bloody devil to come and serve my time.

George William was committed to take his trial at Derby Assizes; “he walked out of the court laughing loudly“.

On December 1st 1897 George William made his appearance at the Assizes, charged with arson, and promptly pleaded ‘not guilty’. All the evidence against him was set before the court and, ‘defending’ himself, the accused questioned none of the witnesses and gave no evidence in his defence. His closing remark to the court was “I would rather be dead than alive; then I would be out of the way”. And because of his previous convictions since 1887, George William was sentence to ten years penal servitude.

Was this the end of George William’s criminal career ?

Not entirely. Simply an interruption … until 1912 !!!

—————————————————————————————————————————————————-

And now we enter Penty Lee’s garden.