Catholics, Baptists and Methodists also set up their own Sunday schools.

Children might also be taught in Dame schools, so-called because many of their teachers were old women.

Charles Dickens introduces us to one such establishment which ‘Pip’ attends in ‘Great Expectations;

“Mr. Wopsle’s great-aunt kept an evening school in the village; that is to say, she was a ridiculous old woman of limited means and unlimited infirmity, who used to go to sleep from six to seven every evening, in the society of youth who paid twopence per week each, for the improving opportunity of seeing her do it. She rented a small cottage … (where), besides keeping this Educational Institution, (she) kept – in the same room – a little general shop. She had no idea what stock she had, or what the price of anything in it was; but there was a little greasy memorandum-book kept in a drawer, which served as a Catalogue of Prices, and by this oracle Biddy arranged all the shop transactions.

“Much of my unassisted self, and more by the help of Biddy than of Mr. Wopsle’s great-aunt, I struggled through the alphabet as if it had been a bramble-bush; getting considerably worried and scratched by every letter”.

From the Minutes of the Committee of the Council on Education 1839-1840:

“In one of these dame schools I found 31 children from 2 to 7 years of age. The room was a cellar, about 10 feet square and 7 feet high. The only window was less than 18 inches square and not made to open. Although it was a warm day … there was a fire burning; and the door, through which alone any air could be admitted, was shut. Of course, therefore, the room was close and hot; but there was no remedy. The damp subterraneous walls required, as the old dame assured us, a fire throughout the year. If she had opened the door the children would have rushed out to light and liberty, while the cold blast rushing in would torment her aged bones with rheumatism.

“…. she had crammed the children as closely as possible into a dark corner at the foot of her bed. Here they sat in the pestiferous obscurity totally destitute of books, and without light enough to enable them to read, had books been placed in their hands.

“Six children of the 30 had bought some twopenny books, but these also, having been made to circulate through 60 little hands were now well soiled and tattered. The only remaining instruments of instruction possessed by the dame … were a glass full of sugar-plums and a cane by its side … “

————————————————————————————————————————-

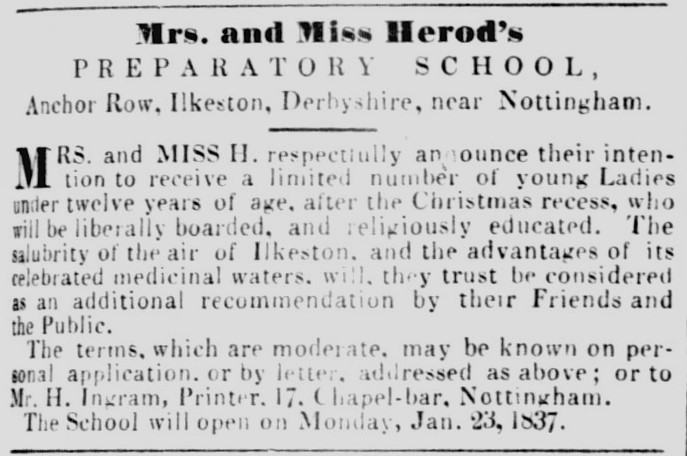

Nottingham Review (January 7th, 1837)

Ilkeston had its fair share of such schools, several of them recalled by Adeline.

— Mrs. Boys, above the British School

— and Miss Straw, of Straw’s Bridge, Derby Road. … this school was opposite the Woolliscroft Store

— At the bottom of Bath Street (a) dame school (was) held by Mrs. Straw, Stanton Road.

— Mrs. Barker, mother of the late George Barker, registrar of births and deaths (she lived in a tiny cottage in Albion Place)

— and Miss Walls, who lived in a two-roomed cottage at the top of Burr Lane.

— There was a Dame’s school in a house on Stanton Road, two doors from the Old Toll Bar, kept by Mrs. Straw.

— Mrs. Ann Wilton Wilson, of Bath Street, was ‘a dear old dame, and all her scholars loved her exceedingly’. (Bath Street) Her son Joseph, builder and joiner, was later responsible for developing Wilton Place.

— In Albion Place was Mrs. Ann Barker, wife of Thomas ‘Worcester’ Barker, another who was kindly thought of by her pupils. She continued to teach into her 60’s, and when a widow, moved from 11 Albion Place to High Holborn, Grass Lane, where she taught from a small room in her house, a ‘class’ of about 20 children, ages 2 to 8. “The older children attended to keep their younger brothers and sisters in order” Her subjects were Reading, Writing, very easy Arithmetic and Scripture, with the children using their own books and slates to learn.

— Close by were Harriet and Miriam Doxey, daughters of Thomas and Elizabeth (nee Gaskill). They had moved their school from Bath Street to Albion House in 1868 and were still there in 1875 when Miriam married book-keeper Edward Wood and moved to Bulwell. Two years later, in January 1877, sister Harriet moved into a large upstairs room in Wilton Place where she was teaching a dozen pupils and charging 12 to 18 shillings per quarter.

— Hannah Small, daughter of George, was a governess and later kept a school in a dilapidated room, next to her house at 21 Church Street, Cotmanhay. The room, with its low ceiling, was big enough for about 16 or 17 children but sometimes accommodated 60! She taught Reading, Writing, easy Arithmetic and Needlework.

And here, below, is the sort of premises found in the area of Hannah’s ‘school’ … this picture showing a cottage in Henshaw’s Nook later Henshaw’s Place, just a short distance from Hannah’s house.

— A ladies’ seminary, at times on Bath Street and then on Nottingham Road, was kept by Miss Eleanor Padman, daughter of Thomas, a Wesleyan minister; ’a lady of very quiet manners but considerable culture and refinement’. (William Strangeway). Writing of the early 1840’s Enquirer places her ladies’ seminary then below the Toll Bar on the Nottingham Road.

She kept a school for about 50 years, 30 of them in Ilkeston, teaching in a room at the house of currier John Glossop and later that of grocer Thomas Riley, both in Bath Street.

— In the late 1870’s and early 1880’s widow Emma Mackintosh kept a small school in Market Street, and then in South Street, using the vestry of the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel. She had up to 30 children , who paid 9d to 1s per week.

— Throughout the 1870’s Hannah Cumberland, wife and later widow of labourer William, lived in Rutland Street and for part of that time kept an infants school in the kitchen of her house.

————————————————————————————————————————-

These dames did have male equivalents — usually for older children (Common Day Schools)

— John Cartwright, born in 1834, recalled his early education.

“My first school in Ilkeston was in the Baptist Chapel Yard, up a flight of steps, and the man who first grounded me in what I am now doing – writing – the man who taught me pot-hooks etc., and who, in the teaching, forgot not the cane, or rather the ruler, and who could box one’s ears to perfection, was a man I always liked, and whose memory I always cherish, his name was (William) Milner……In those days we had (steel) pens for small-hand, text-hand, round-hand, and large-hand, and for years afterwards quill pens were much used in shops, warehouses, and offices. Mr. Milner was after appointed master of the British School, in Bath Street, where I accompanied him…”

— Then there was Mr. Charles Crossley, who kept school in an upper room in Pimlico, above the home of Abraham Mitchell, cordwainer, another ‘flourishing school, highly thought of’. (Bath Street)

— Another ‘famous home for learning’ was that of William ‘Billy’ Pitt in Bath Street, expert calligraphist, ardent politician and ready wit.

When his landlord suggested raising his rent, Billy replied ‘Thank you, sir, for I cannot raise it myself !’

He would chew any amount of tobacco up to about half-an-ounce. And instead of looking at children’s hands as they went into the classroom to see if they were clean, he would examine them as they came out, when some of them had dirtied them by cleaning their slates — in which case they got a dose of the cane, with an extra stroke if they flinched during their ‘punishment’.

— In Lower Granby Street, Ephraim Davis taught 160 scholars in a room measuring 27 by 20 feet, seven feet high to the eaves, and a further seven feet to the centre of the roof, and ‘with most imperfect ventilation’. (The Local Board)

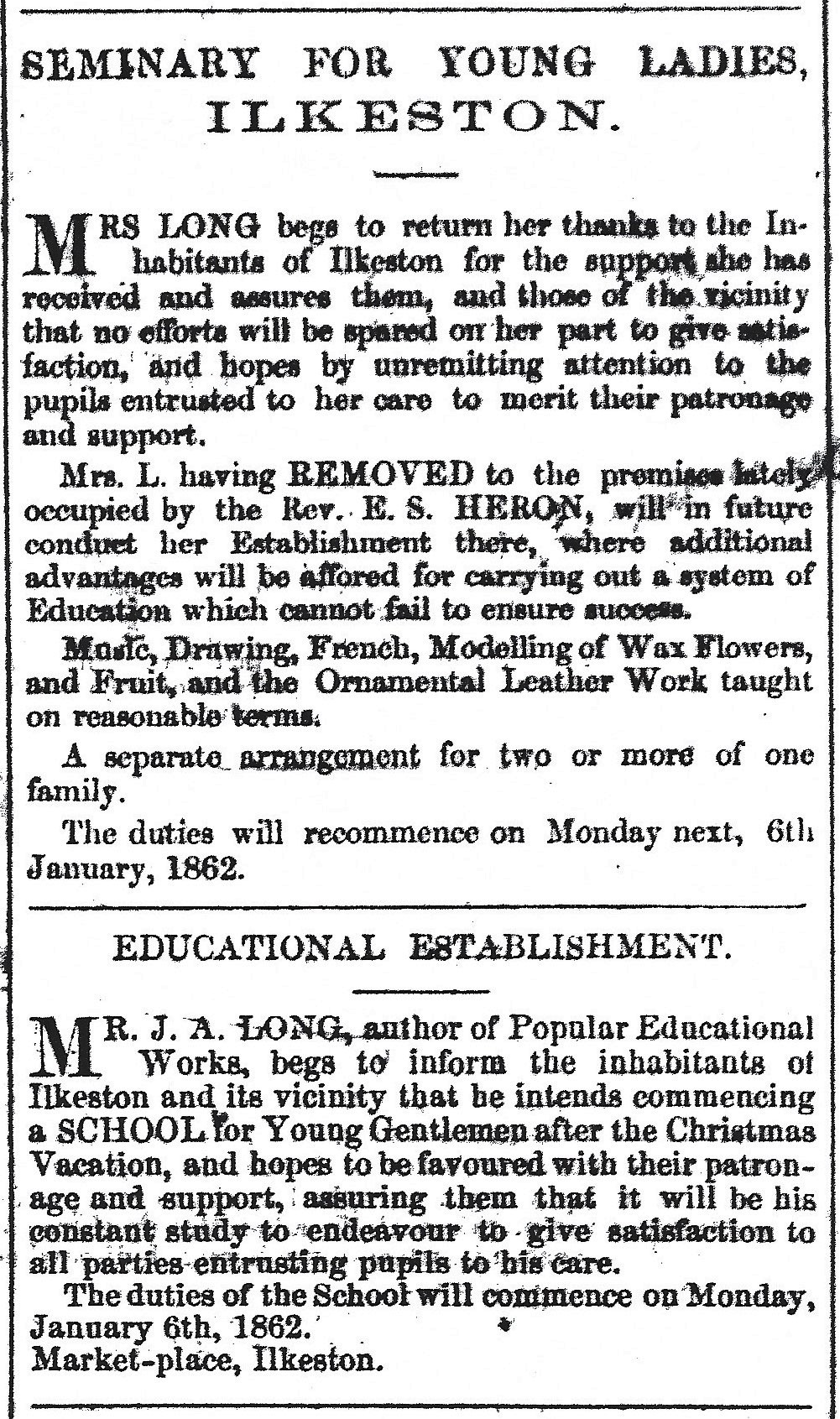

“A Mr. Long came to Ilkeston when I was a child and started an Academy for boys.

He lived in Wilton Place and had for his schoolroom the old Baptist Chapel in South Street.

I remember seeing the boys marching two by two from Wilton Place to the Schoolroom.

Mr. Long died rather suddenly”.

John Potter Atkins Long was a schoolmaster in Wakefield, Yorkshire for many years before he and his family came to Ilkeston in 1861 and established his school here in January 1862.

“Mrs. Long started a girls’ school in Wilton-place. After Mr. Long’s death the family removed to a smaller house in Wilton-place, and Mrs. Woolliscroft acquired the house they had moved from.”

John Potter Atkins Long died in Wilton Place in December 1867, aged 57, and his widow Elizabeth (nee Milsome) continued as schoolmistress at 5 Wilton Place.

Shortly after the Long family arrived in Ilkeston Elizabeth had established her ‘Seminary for Young Ladies’ in the premises previously occupied by the Rev. Ebenezer Sloane Heron in Chapel Yard, Pimlico. The latter had left Ilkeston in December 1861.

— Later on a Mr. Horsley started a school for boys. He lived in East-street nearly opposite the late Mrs. Bennett’s Wine Vaults in one of two tall houses. For schoolroom he had a large vestry in the South-street School. He had a many pupils, and I believe death was the cause of the closing of the school.

Sheddie Kyme also recalls this private school in East Street known to him as ‘Horsley’s’.

Joseph Horsley was born in Leeds in 1816 and appears on the 1841 census in the Wortley district of that city where he traded as a tailor. By 1851 he has moved south to Derby where he was now a master baker and confectioner employing two men. And by 1861 he had made his appearance in Ilkeston, at Pigsty Park, North Street, as a woollen draper and tailor.

Sometime within the next ten years he moved to No. 4 East Street where he established his ‘Preparatory, Classical and Commercial School’ on January 4th 1869. Joseph was described as ‘schoolmaster’ on the 1871 census.

Within three months, to provide more ample accommodation, he had moved his school into Spring Lane, into a room adjoining the Primitive Methodist Chapel there. Hours of attendance were 9 to 12 a.m. and 1.30 to 4 p.m.

Joseph’s wife Mary died in East Street in 1870, aged 70, and also immediately Joseph married again, to a woman almost 40 years younger than Mary.

The bride was widow Elizabeth Ann Bexon (nee Ambler). Born in Barnsley she had married her previous husband there in 1861. He was blind shopkeeper William Bexon, born in West Hallam.

Now Joseph had two step-children – Mary Eliza and George Arthur – and before the family left Ilkeston about 1872 it had grown with the birth of Elizabeth Ann Ambler Horsley in 1871.

They moved on to Heap, near Bury in Lancashire, where Joseph was now a ‘commission agent’.

By 1891, still at Heap, Joseph was styled as a ‘local preacher’ and he died there and in that year.

None of these provided free education of course but were usually cheaper than the fees of other schools; Bath Street recalled paying 8d a week for his schooling, and provided his own books.

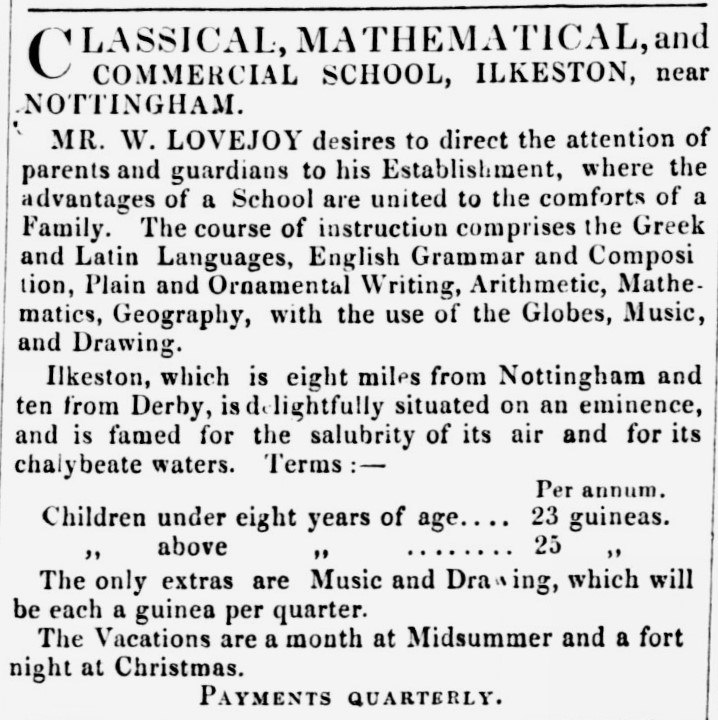

— and for those of a ‘higher order’, who could resist the charms of Ilkeston or the new School of William Lovejoy, as advertised in the Nottingham Review of July, 1850 ?

Like the academy of William Milner (above), this was located in the Baptist Chapel Yard area of South Street

————————————————————————————————————————-

Before we move on to the town’s Market Place let’s pause to look at a very interesting and unique item in Ilkeston’s Education History … the very first edition of Hallcroft Boys’ School magazine, 1925, called The Crofter, very kindly sent to me by Blidworth and District Local History and Heritage Society

————————————————————————————————————————-