Hello Mr Small !!

Adeline leads us on, up towards the corner of Bath Street and East Street where we find that “next to the ‘Pioneer’ office was Mr. George Small’s seed and vegetable shop. Thee shop had two small windows, one in Bath Street the other, a small bow window, in East Street. The door was on the corner. Mr. Small also had the nursery gardens in the Lawn.” This shop and the adjoining Pioneer offices were later to become the Borough Arms Inn. In 1871 it was numbered as 116 Bath Street and by the close of the Victorian era was number 2 Bath Street. (As there were now only even numbers on this side of the street, it had to be number 2 !!)

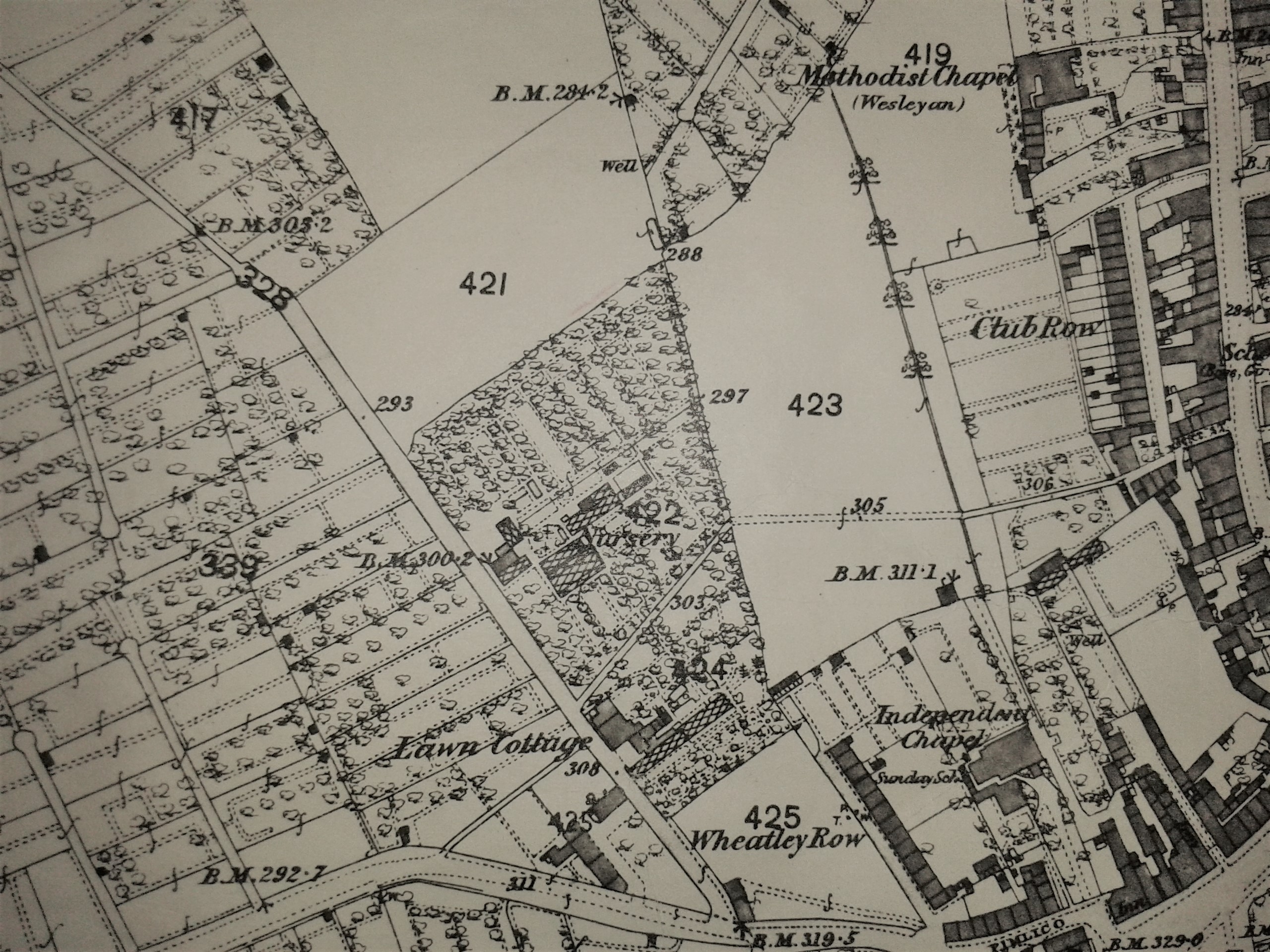

We can see Lawn Cottage, home to the Small family, on the map (below), to the west of Club Row. Note the lack of housing in this part of the town. If you look closely at George Small’s nurseries, you should see his greenhouses too.

If we were looking for the site of Lawn Cottage today we would find it almost exactly where the pedestrian in the photo (below) is walking. She is outside the Croft Yard Reservoir in Pimlico. The nursery would be at the north end of the same reservoir.

Croft Yard Reservoir c. 1975 (Jim Beardsley‘s collection)

George was involved in a civil court case in February 1843 when he was sued by Samuel Fletcher (described as a blacksmith) for the full cost of work on a drilling machine. At that time George was described as a “nurseryman, seedsman, florist, grocer, tax collector, constable, lime-burner and boatowner” — the village Caleb Quotem (a sort of ‘Jack of all trades’). However it is only some trades out of that list which we will focus on.

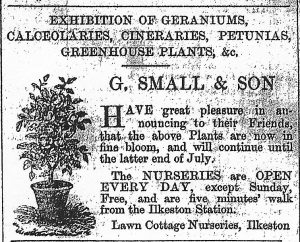

It was from these nurseries that George conducted his very successful and esteemed business for many years — not just for profit but also for prestige. His ‘produce’ was of such a high quality that it was entered in many local competitions and shows, and with great success. For example, in the summer of 1855, at the Nottingham Floral and Horticultural Sociey’s Annual Meeting at the Nottingham Exchange, George won a dozen first prizes and three second prizes, his speciality being geraniums !! And this was not an isolated event for the ‘respected townsman‘.

Born at Shepshed, Leicestershire in 1805 George Small was the son of Lambert, gardener, and Elizabeth (nee Draper) who came to live in Ilkeston where George married Frances Lane, daughter of Cotmanhay butcher Thomas and Hannah (nee Shelton) on November 29th 1825.

By 1833 George had achieved some importance within the Ilkeston community, for in that year, he was nominated to be an Overseer of the Poor at the Vestry meeting. He had already served as the Parish Constable for about three years.

Both George’s parents died in 1834, leaving him in control of the business….Small & Son of the Lawn Cottage Nurseries in Ilkeston, and others at West Hallam.

George had taken over the premises on the corner of East Street and Bath Street from butcher William Fritchley in 1843 and quickly converted them to sell his seeds, flowers and vegetables. His shop — a colour-washed structure with a roof of thatch — had one small bay window facing East Street, the other on Bath Street, and between them a corner door.

In November 1866 George’s son William — who was then landlord of the Bull’s Head Inn at Little Hallam — took over this shop to trade as a butcher.

In early 1867 the firm of George Small & Son finally moved its seed shop from the East Street premises to the warehouse at the Lawn Cottage Nurseries in Pimlico.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

The Evil-doers.

George was also one-time Parish Constable, ‘a terror to evil-doers’, and had served in that capacity ‘without fear, favour or affection’ since 1830. The origin of George’s nickname comes from the Bible — Proverbs 21:15 which states that “when justice is done, it brings joy to the righteous but terror to evil-doers” … meaning that George would always handle a case appropriately and deliver a just and correct verdict.

One of his assistants was Arnold-born framework knitter Thomas Horsley, recalled by Enquirer….

“One time a man had misbehaved himself at Mr. Hives, the Rutland Arms. Horsley was sent for to remove or apprehend him, but the man would not go with Horsley; he said he would not be taken by a deputy. Mr. Small was fetched, and the man went quietly with him”

Another ‘evil-doer’ was Mrs. Mary Ann Hill, aged about 40, who in March 1852 was housekeeper to William Rollinson (or Rowleston) at the Three Horse Shoes Inn in Derby Road — or Moors Bridge Lane as it was then called. She left this establishment ostensibly to go to her mother’s funeral near Basford but not before taking with her William’s silver watch, a quantity of silver spoons, a silver sugar bowl, a metal teapot, one bell, several items of clothing, sheets, table cloths, a banker”s draft for £70 and notes and coins not belonging to her.

Old William was infirmed and lame, had lost his wife Mary just over a year before, and had employed Mary Ann to be his housekeeper while a man called Robert Mathers was his ostler and brewer. This man left at the same time as the housekeeper.

Constable Small was quickly on the case of the ‘disappearing duo’.

After making enquiries, he hired a horse and gig, drove to Derby railway station, took the 2.15am train to Liverpool, arrived there at 7am, and within hours had apprehended the thief with her accomplice at a lodging house. They were just about to sail for America but now instead had to make a return trip to Ilkeston and a date at Derby Assizes.

At their trial in July, where they were both found guilty, the judge commented that they had wanted to travel abroad and he would not disappoint them — they were each sentenced to ten years’ transportation.

In consequence of the introduction of the new police force in the parish in 1857, George’s duties as high constable in summoning juries etc. would be terminated.

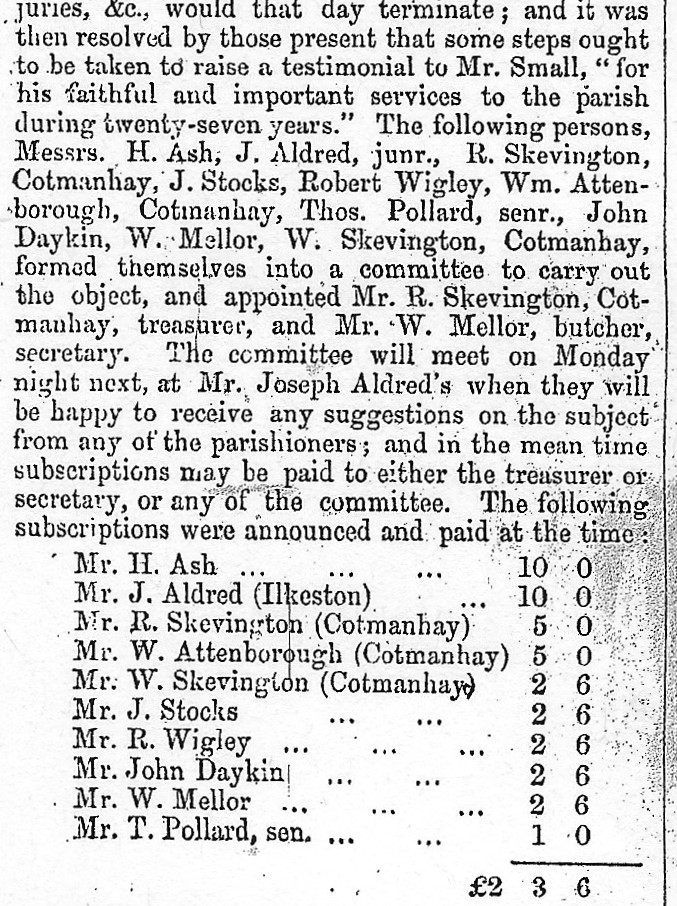

On July 30th the Pioneer reported that a committee would be set up to decide upon how to show appreciation for George’s ‘tried and trusty services to the parish of Ilkeston’,…. over 27 years.

On the right you can see the list of prominent tradesmen who wanted to show their thanks to George … many had benefitted from his services !!

And all the while George’s trade continued briskly

Acting in his parochial capacity, George was the subject of a most shocking experience in April 1857 when he was summoned to a house near the toll bar in Nottingham Road (White Lion Square).

This was the residence of framework knitter Annice Wigley, daughter of Patrick and Hannah (nee Loxley), who had arrived at Ilkeston from Bonsall via Basford and Nottingham about 1851 with two illegitimate children — and who added to that number whilst in Ilkeston.

Complaints had been made about the treatment of these children…. that they were unattended, shut up in the house and left without food.

With the assistant overseer, George went to the house, forced open the door to gain access and found several of the children huddled around a dwindling fire. The eldest was about eight years old while the youngest, Patrick Ward Wigley, was just six months. Their weights, recorded in the local newspapers, ranged from just under two stones (about 12 kilograms) down to just over a stone.

A small quantity of bread was found in the house and the eldest son was reported to have been given a piece of bread by a neighbour that morning. He didn’t have it for long — his mother had beaten him for it, taking him by the hair and banging his head against the wall (it was reported).

“The children were employed in sewing hose, and the mother’s object appears to have been to pine them to death, and while doing so, to work their fingers while life remained”.

Because of the alleged violence, a summons was taken out against Annice but she had already left the town. Consequently the children were taken into care and temporarily housed at Basford Workhouse where they soon began to put on weight and “were well sunburnt, which showed they had been in the fresh air”.

Under magistrates orders they were soon removed to Bonsall.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

The new Police Force

On May 21st 1857 the Police Force arrived in Ilkeston as a result of the County and Police Act of 1856.

Mr. Fox, chief constable, and Mr. Mousley, superintendent of the Belper District, appointed Sergeant Thomas K. Powell to serve in Ilkeston.

Almost immediately the latter took “energetic and determined measures .. for the peace, safety and comfort of the inhabitants generally”.

The Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal believed that “ere long, Ilkeston, the scene of many a drunken brawl and street disturbance, will eventually become one of the most peaceful as well as one of the most flourishing country towns in the midland counties”.

left, a Police Constable in 1857 (http://gallery.nen.gov.uk/asset90812-.html)

Within three days of his arrival the sergeant had been out on the streets, early on Sunday morning and had ‘nabbed’ Benjamin Goddard for being drunk. George Ball, county police constable, and Samuel Smith of the county police force, companions of the sergeant, had both been roaming the streets at the same time and had ‘bagged’ their own brace of drunkards. All those detained had presumably sobered up by the time they appeared at Smalley Petty Sessions two days later, to be fined.

For good measure, the police also charged Joseph Aldred, landlord of the Old Harrow Inn, with wilfully allowing drunkenness and disorderly conduct on his premises — the same constables had entered the Inn that same weekend to discover several drunk customers, one lying flat on the ground, and six prostitutes, using indecent langauge, also present. Joseph too was fined.

And the following weekend the police were again scouting around the area with the same results. It appears that a conscious policy was being adopted towards the drinking population of the town, and they certainly had a large crop of prospective ‘clients‘ to chose from.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

More evil-doers

In the late autumn of 1865 George noticed that his nurseries began to lose a lot of their stock but was unable to explain why or how. That is until two of his workmen, William Bostock, son of ‘Jonty Trot’, and Joseph Rice, caught a young man, lacemaker William Foster, acting suspiciously in one of the orchards and who calmly stated that he had come for a few apple trees. He was equally calmly taken into custody.

During the following day Inspector Brady, aided by George’s oldest son Lambert Small, made enquiries in the town and began to uncover some startling facts.

Young Foster had developed quite a ‘tree-trafficking trade’, supplying contraband apple trees to needy clients around the town, and further afield. His Bath Street customers included currier George Tooth who had been supplied with one apple tree to plant in his garden, cordwainer John Chadwick had bought four apple and one plum tree as well as a gooseberry bush, the Poplar Tavern of Marina Ebbern was supplied with a pear and a plum tree, tallow chandler Moses Mason had benefited from six apple trees, while William Jones at the Brunswick Hotel had received four plum and two apple trees.

Young William hadn’t ignored other parts of the town however. Mining contractor John Phillips in Spring Lane now had an additional five apple and two plum trees along with six gooseberry bushes, and contractor Ezekiel Phillips in Heanor Road got six ornamental shrubs.

And of course the Foster family had to be considered!! Father John Foster alias ‘Milko Jack’ was found with three standard apple trees, while William’s brother-in-law John Taylor alias Foulds of Nottingham Road had one apple tree, one pear tree and 12 blackcurrant bushes in his garden, plus two plum trees in his coal-house.

A couple of apple trees had ’escaped’ across the county border into the garden of farmer John Fritchley at Cossall Marsh.

At his subsequent trial at Smalley Petty Sessions — where he quickly pleaded guilty to theft — it emerged that William had supplied trees to order and at cut-price, and that the total value of the stolen goods was at least £3. When fined 9s for the trees with £2 18s 6d costs, William claimed poverty and was thus granted a two-month stay in prison, accompanied by hard labour.

It was often the practice at Petty Sessions to offer the accused the choice of a fine or a term of imprisonment.

And then there was Selina Sudbury, a ‘not so evil-doer’

And not forgetting George himself !!

In 1870 George and a son were convicted of careless driving, as they were leaving Derby market in their horse and cart. Not taking sufficient notice, they collided with the horse and trap of Derby contractor Joseph Tomlinson, who subsequently sued them at Derby County Court.

No points on their licence but a £31 penalty – the money went to Joseph for the sad loss of his mare, so badly injured that it had to be shot.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

The Small family of George and Fanny

Adeline remembers that “George had three sons. Lambert was with his father, Thomas at Mr. Carrier’s, and George was also in the gardens. Martha was at home, Nelly was in attendance at the shop.” In fact there were ten Small children.

Hannah (born in 1826) went to live with her grandmother Hannah Lane in Cotmanhay. She died, unmarried, in Church Street in June 1879.

Elizabeth (1828) married farmer Christopher Shepherd of Smithy Farm in Morley in January 1864. Their only surviving child was Christopher George who later became a civil engineer.

Farmer Christopher died in 1872 and ten years later Elizabeth married widower Henry Samuel Ash, (brick maker), leather goods manufacturer and surgical hosiery, bandage and brace maker of Upper Parliament Street in Nottingham.

After the death of her father in 1877 and before her second marriage Elizabeth acted as manageress to the firm of Messrs. Small and Son, nurserymen, until it was sold in July 1882 to son William.

Lambert West (1830) was an assistant to his father. He married Elizabeth Winson in February 1865.

One Monday evening in 1869 he was at the nursery in Lawn Gardens hunting rabbits which were damaging the shrubs. Gun in hand he was climbing over a fence to retrieve a wounded rabbit when the gun trigger caught in the fence, discharging the loaded weapon. Lambert was shot in the hand and had to have the thumb and first finger of his left hand amputated.

Lambert died suddenly and unexpectedly in 1872, aged 41, with a ‘liver complaint‘ (cancer of the liver).

Thomas Henry (1833) was an apprentice with Joseph Carrier, draper of Bath Street, before opening his own linen and woollen drapery store, one door below the British School, in the premises previously occupied by Messrs Whitfield Brothers (drapery, hosiery, boot and shoes) in 1866.

William West (1835) was a butcher who in September 1865 married Harriet Frances Sharp, the second daughter of Nottingham coach builder Freeman and Elizabeth (nee Strelley). After this, William went to live at Little Hallam, trading as a butcher and publican of the Bull’s Head Inn.

In 1872 and a few days before the death of his brother Lambert, William had allowed a November 5th bonfire celebration in his croft, close to the Bull’s Head. Unable to obtain fireworks and in an effort to amuse the on-looking children, a servant lad of William’s had taken along an old single-barrelled gun which he charged and tried to fire unsuccessfully. So he charged it once more and tried again, this time with fatal consequences but not for himself. The barrel exploded and a piece of metal lodged in the neck of young James Wilkinson, seven-year old son of Isaac and Elizabeth (nee Straw) of Little Hallam. Dr. Norman attended and when the child died nine days later, the doctor gave his opinion that death was the result of the bursting of a gun.

In November 1874 William was involved in an interesting legal case when he was fined at Ilkeston Petty Sessions for preventing William Bickley, the Inspector of Nuisances, from entering his premises to inspect for diseased or unwholesome meat.

The case centred on the Nuisances Removal Act of 1855 (amended 1863), which allowed the Inspector to enter premises where meat is sold, at any reasonable time without notice and without impediment or obstruction.

The suspicions of the Inspector had been aroused when he heard that William had sold a piece of meat unfit for food on Saturday night. Many unscrupulous butchers sold their bad meat at the ’poor man’s market’ late on Saturday night in the knowledge that they could escape a Sunday visit and a search from the Inspector, thus giving them extra time to get rid of any remaining incriminating evidence.

However William did receive a Sunday visit at his Bull’s Head home when the Inspector came to examine the slaughterhouse there. This inspection revealed nothing amiss. Mr. Bickley then asked to enter and search the butcher’s locked shop in Ilkeston Market Place. The butcher said he was welcome to call on Monday morning when the shop would be open but he refused an immediate inspection – he would not give up his key and would do nothing else to help the Inspector who was thus faced with the choice of either breaking down the shop’s door or leaving. He chose the latter course of action.

Later that Sunday, about seven or eight in the evening — and it was dark — lace maker William Carrier was standing in the Market Place with a few friends when he saw shadows of figures moving in the butcher’s shop. Eventually, and under cover of the darkness, William’s wife Harriet and another woman emerged from the shop, the latter carrying a bundle.

On the following Monday the Inspector visited the butcher’s Market Place shop but found no ‘dodgy’ meat. But this did not stop him from charging William for his refusal to allow inspection. At the Petty Sessions William was fined £1 and 30s costs.

In June 1875 the butcher appealed against his fine at the Court of Queen’s Bench in Westminster. His argument was that Sunday was not a ‘reasonable time’ to call as the business was not then open, and in addition he had done nothing to obstruct or prevent the inspector from entering, but merely refused to travel a mile to open up his shop. The judges decided that the second part of the butcher’s argument was the one on which they could allow his appeal, as they agreed that he had done nothing to openly obstruct the Inspector. Thus they reversed butcher William’s conviction but remarked that the law should be altered to clarify the position and powers of the Inspector, and to render parties liable to penalties in such cases.

In March 1875 William gave up his licence at the inn to John Harris, victualler of South Clifton near Nottingham, but by 1891 the inn was back into the hands of William’s family. (see The Wilkinsons)

In January 1892 William made another of his occasional appearances before the magistrates, when he was summoned by the Town Council, as the Urban Sanitary Authority, for ignoring a notice which had been served on him in the previous October. He owned property in Little Hallam and in one of his houses, occupied by Joseph Fletcher and his family, he had allowed too many people to live. There was a kitchen and two sleeping rooms, and yet nine members of the family lived there, the eldest child being 18 and the youngest just two. William had been warned that he must reduce the number of ‘inmates‘, a warning which William chose to ignore. He was issued a preliminary fine of 10s with 13/6d costs — and another warning that he must obey the previous warning without delay, or he would be fined more heavily !!

And William couldn’t immediately walk out of the court because he faced another charge !! In the Fletcher house and three neighbouring ones, all owned by William, the drains were blocked and the outhouses out of order. He had been served with a notice to rectify these defects, but this hadn’t been done. Now he must put in new 6in drain pipes, with proper joints and traps, and repair the outhouses, with doors, coverings and seats — all within 14 days and paid for by himself, or another fine of £1 was coming his way !!

And William wasn’t the only one of his family to give employment to the magistrates … it seems that his wife Harriett could let her temper lead her astray.

The Smalls had horses which often strayed into the field of their neighbour Eliza Lane and which had always been returned to its owners — except on one day in July 1883. Now Mrs. Lane asked her daughter Eleanor, wife of warp hand Emanuel Barker, to lock them into the field, an action which prompted Harriet Small to storm to the neighbours, carrying her husband’s meat cleaver for comfort. She then threatened to chop Eleanor’s head off, struck her in the mouth, causing her lips to bleed and loosening a few teeth; all these actions accompanied by some ‘ripe’ language. … and all confirmed by Eliza Lane and Eleanor Barker.

And of course, all denied by Harriet Small when she appeared at Ilkeston Petty Sessions … no assault had occurred and she was the victim of slanderous slurs, being called ‘a drunken beast’ when she had never had a drink in her life !!! Rather difficult of course when your husband has been a licensed victualler for nearly 20 years.

Harriet had to pay a 5s fine with costs.

And William’s son, William junior, contributed to the family crime sheet. For example, one night in January 1893 P.C. Burdett found the son asleep in his cart, while his attached horse waited quietly and patiently. Thus William was guilty of being ‘in charge‘ but ‘not in control’. His defence was that he had been thrown from the cart on Trowell Moor and knocked senseless; someone had kindly put him back in the cart, and he couldn’t recall anything until he arrived back home. He was not asleep and definately not drunk !!! — fined 10s and 4s costs.

In September 1894 William senior was still the landlord of the Bull’s Head, and was still managing to get himself in bother with the authorities. This time he had been selling beer and whiskey in a tent at the back of his premises which was over 100 yards away .. and there was a dispute over whether his licence allowed him to do that. The police had warned him about this but William had stubbornly continued to sell liquor on a second occasion a couple of days later. It turned out that William was in the wrong but that he could have got an occasional licence for 1s which would have covered him, to sell outdoors. He had saved a shilling on the licence but had landed himself with a fine totalling £7 with £8 6s 6d costs !!! At least William’s licence wasn’t endorsed !! It didn’t really matter however, because in December 1894 the licence was taken over by Godfrey Beardsley.

And as the Victorian era was drawing to a close, William was having to deal with miscreants sneaking into his premises and helping themselves, just as his father had had to do, earlier (see William Foster, above). On August 13th, 1899 he had caught three lads — brothers Isaac and William Sneap, and Ernest Clarke — “scrumping”, stealing 2s worth of apples from his Lawn orchard. He managed to collar them, with their bosoms and pockets full of apples, although the group of ‘receivers’ lurking outside the orchard scarpered when he arrived on the scene. He had staked out the property for several weeks and at last this had paid off, but not before a great deal of damage had been done to the trees and hedges.

Only Ernest appeared in court at the first hearing when he was fined 8/6d including costs: the Sneap brothers turned up a week later and were fined 10s including costs.

William Small died at the Lawn in October 1904. And Harriet on June 6th 1909.

Under new management … the Bull’s Head Inn. Can you spot the name over the door ?

Joseph Wheatcroft (1837) was a joiner and builder, married Emma Sears in 1865, and later moved into beer retailing. From 1866, he kept the New Inn, previously in the hands of Arnold Harrison, and on land owned by his father at the top of Bath Street. This is not to be confused with the other, later, New Inn, at the corner of Providence Place and Bath Street.

In September 1874 he was refused a licence to sell wine and spirits.

The 1881 census shows Joseph Wheatcroft as keeper of the Erewash Hotel on Mansfield Road in Langley Mill, the licence for which had been transferred to him from Thomas Milnes in November 1877. In June 1882 he purchased the Old Harrow Inn in Ilkeston Market Place and at his death in 1884 he was still the landlord there, a position which his wife Emma inherited. (The New Inn had passed into the occupation of Robert Bamford in November 1879)

Martha Hale (1839) was housekeeper in the Small household until 1876 when she married the Reverend William Popplewell, Vicar of St. Thomas’s Church in Halliwell, Bolton and went to live there, after a honeymoon at Llandudno. The venue for the wedding ceremony was the parish church at Horsley as Martha’s brothers, George and Thomas, were now the chief employers of labour in this coalmining area. The roads and houses in the nearby village of Kilburn were decorated with bunting, flowers and evergreen for the occasion.

George junior (1841), a civil engineer, married Emma Caroline Sharp, sister of Harriet, in 1864.

By 1874 he was proprietor of the Kilburn Colliery and held a mining certificate under the Mines Regulation Act of 1872 – this stipulated that all pit managers had to have state certification of their training.

Emma Caroline died at Darley Field House in Derby, December 1875, aged 33, and in 1879 George married Clementina Holbrook.

Seven months after registering the deaths of his parents at the beginning of June 1877, Henry Huntley (1844) died at the Poplars in Kilburn in 1878, his age incorrectly recorded as 30. His body was returned to Ilkeston and buried at St. Mary’s Churchyard.

Like her brother Thomas, Mary Helen (Nelly?) (1847) stayed with her parents until they died and then left Ilkeston with Thomas to live at Smalley. In 1883 she married Derby architect and surveyor Michael Robert Evans.

Thomas Henry and George Small junior were declared bankrupt in December 1885. At that time they had debts of about £20,000 and assets of nominally only one-fifth of that amount, though in ractical terms, much less. Eventually the Bankruptcy Court devised an arrangement whereby the Small bothers would be liable to pay to their creditors $4000, a sum which would be reduced in stages should the debtors meet repayment deadlines. However, a couple of months before this arrangement, the pair sold the Kilburn Colliery to William Wilde who continued operating the mine until September 1889 — when he too was declared bankrupt. What made the situation more complicated was that the Small brothers were owed money by William. After more complicated arrangements it was agreed that this money — reduced to £500 — should go straight to the parties who were owed money by the Smalls, as part of their bankruptcy agreement.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

The Broken Heart Syndrome

Fanny Small died at Lawn Cottage on May 31st 1877, and husband George just two days later, on Saturday, June 2nd 1877, aged 70 and 71 respectively.

George had been unwell for some time, suffering from a rheumatic complaint, and had not been able to walk for a year or two, such that his death was not wholly unexpected.

The following Tuesday afternoon saw their polished oak coffins — made by William Warner — carried together along Pimlico to the parish church to be buried in the churchyard extension.

“Muffled peals were rung on the church bells during Sunday and after the ceremony”.

The Nottinghamshire Guardian thought that there had been no previous instance of husband and wife being interred at Ilkeston at the same time within the memory of any resident.

George and Fanny had been together as husband and wife for over half a century.

In a newspaper article (Guardian, January 9th 2015) Dean Burnett suggested that there may be a scientific explanation why some elderly couples, who have been together for decades, die within a few days of each other .. the ‘broken heart syndrome’.

The mental anguish and grief caused by losing a loved one can create stress which can then lead to numerous physical ailments, so serious that they may affect the heart. But even without direct heart damage an aged, frail and rundown body cannot cope with the shock of losing a long-term partner .. with fatal consequences.

In March 1878 their son Thomas Henry of Kilburn Colliery offered the gift of a richly-stained Eastern window to the Parish Church at Kirk Hallam in memory of his parents. The estimated cost was £700.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

The New Inn … later was known as the Borough Arms

As noted above, George Small’s property also housed the New Inn beerhouse in the early 1860’s — and kept by Arnold Harrison from 1863 until 1866.

In November of 1878, part of the estate of George Small senior was up for auction. This was the ‘well-accustomed and old-established’ New Inn beerhouse (occupied by Thomas Burnham), a butcher’s shop and adjoining dwelling house with frontages in Bath Street and East Street, occupied by William Small, and another adjoining grocer’s shop and dwelling house in East Street, occupied by Stephen Rose.

“Enquiries to Thomas Small of Kilburn or Joseph Small of Langley Mill”. (Joseph was at that time landlord of the Erewash Hotel at Langley Mill).

According to the Pioneer the premises were sold for a total of £2175.

In September 1884 the same copyhold properties were being offered at auction by the trustees of the estate.

Since November 1879 the New Inn had been occupied by Robert Bamford and was now described as having a tap room, bar, club-house, sitting room, kitchen, excellent cellars and three good bedrooms.

Also up for auction was an adjoining butcher’s shop occupied by William Small, and round the corner, at 1 East Street, a dwelling house and grocer’s shop, occupied by Mary Rose (nee Aldred), widow of Stephen and daughter of cordwainer Samuel and Lucy (nee Scattergood). The properties were sold at that time for the reserved price of £1500 to Joseph Small of the Harrow Inn, though not at the auction where they just failed to reach the reserve.

The Ilkeston Advertiser noted that 15 years earlier the same property had been offered for sale at auction but had been withdrawn at £2000.

For a time Ilkeston was blessed with two New Inn beerhouses and in 1885 both were represented at the Petty Sessions. William Trueman, keeper of the northern New Inn, was there unsuccessfully defending a charge that he had allowed gaming on his premises viz. he had played a couple of games of skittles for beer. Meanwhile George Scattergood, keeper of the southern New Inn, was more successful. He faced a charge of allowing his premises to be open after 11 o’clock at night but when he showed that he was entertaining only friends the case was dismissed.

In April 1887 the former George Small premises were owned by Messrs. Shipstone and Son, brewers of Basford, when a fire broke out in the thatched roof of widow Rose’s shop. The fire brigade arrived and eventually got control of the blaze but not before the roof was destroyed and the building rendered uninhabitable. Fortunately Mary’s personal goods were rescued from the cottage by willing neighbours.

From September 1886, Herbert Moon had been landlord at the New Inn beerhouse but it soon led to financial difficulties for him. In August 1888, seriously in debt he was forced to give it up, and with his wife, moved to be caretaker at the town’s isolation hospital for infectious diseases at Little Hallam (at a salary of £50 per annum). The licence was then taken over by Adkin Toplis. And at he time he took over the inn, he reckoned that it had the nickname “The Cow Shed”.

By September 1890 Ilkeston Borough Council had received a letter from Adkin Toplis, now the landlord of the New Inn, who had recently changed the name of his beerhouse to the Borough Arms. He was now seeking permission to use the borough arms on a ‘Painted Sign’ for his beerhouse; the arms were the property of the Corporation and could not be used without consent of the Council. Permission was granted and hence on the 1891 census we find Adkin now at the Borough Arms. He was still there until December 1899 when the licence was transferred to George Spencer, who was there to see out the Victorian era.

The Borough Arms (on the right) in the recent past … from the collection of Jim Beardsley.

Across Bath Street is the Harrow Inn corner.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

There was another ‘New Inn‘ at the corner of Providence Place and Bath Street, which we shall visit later.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

The Horsleys

George Small’s one-time assistant Thomas Horsley had married Hannah Hutchinson in 1828; she was the daughter of Joseph and Catherine (nee Beardsley).

Like his father, their only son Joseph was a renowned cricketer of the town – “I well remember the old man bowling slow underhands in cricket matches, and doubtless he it was who taught Joseph to be such an ‘artful dodger’ in the way of getting at an opponent’s weak spot”. (John Cartwright)

Having played for Ilkeston Rutland Cricket Club, by the 1866 season he was engaged professionally at Everton, Liverpool where in the first nine weeks he scored 64 runs and took six wickets per innings.

In the 1867 season Joseph was playing cricket for Leeds Clarence Club which had engaged him as a ‘professional’. In August of that year, batting at their Kirkstall ground against Boston Spa, he scored 173 runs in over six hours. When he went in the score was 59 for 1 and by the time he was out it had risen to 379 for 6. Boston Spa never got time to bat and the match was a draw.

In a match against local rivals Gledhow Club at the same venue a month later Joseph scored another ‘ton’ — 114 runs – almost without giving a chance. Not content with that, seven wickets fell to his credit in the first innings, three being bowled by Joseph.

Man of the Match …. Ilkeston Pioneer Sep 12th 1867

Man of the Match …. Ilkeston Pioneer Sep 12th 1867

A week later at the same ground and Joseph enjoyed his ‘benefit match’ played between the ‘Gentlemen’ and the ‘Players’ of Leeds District. But he didn’t enjoy it too much. He was out for a duck..

However, during that season, Joseph took a total of 104 wickets for 630 runs – an average of 6 runs per wicket.

In 22 innings he scored 716 runs, twice not out.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

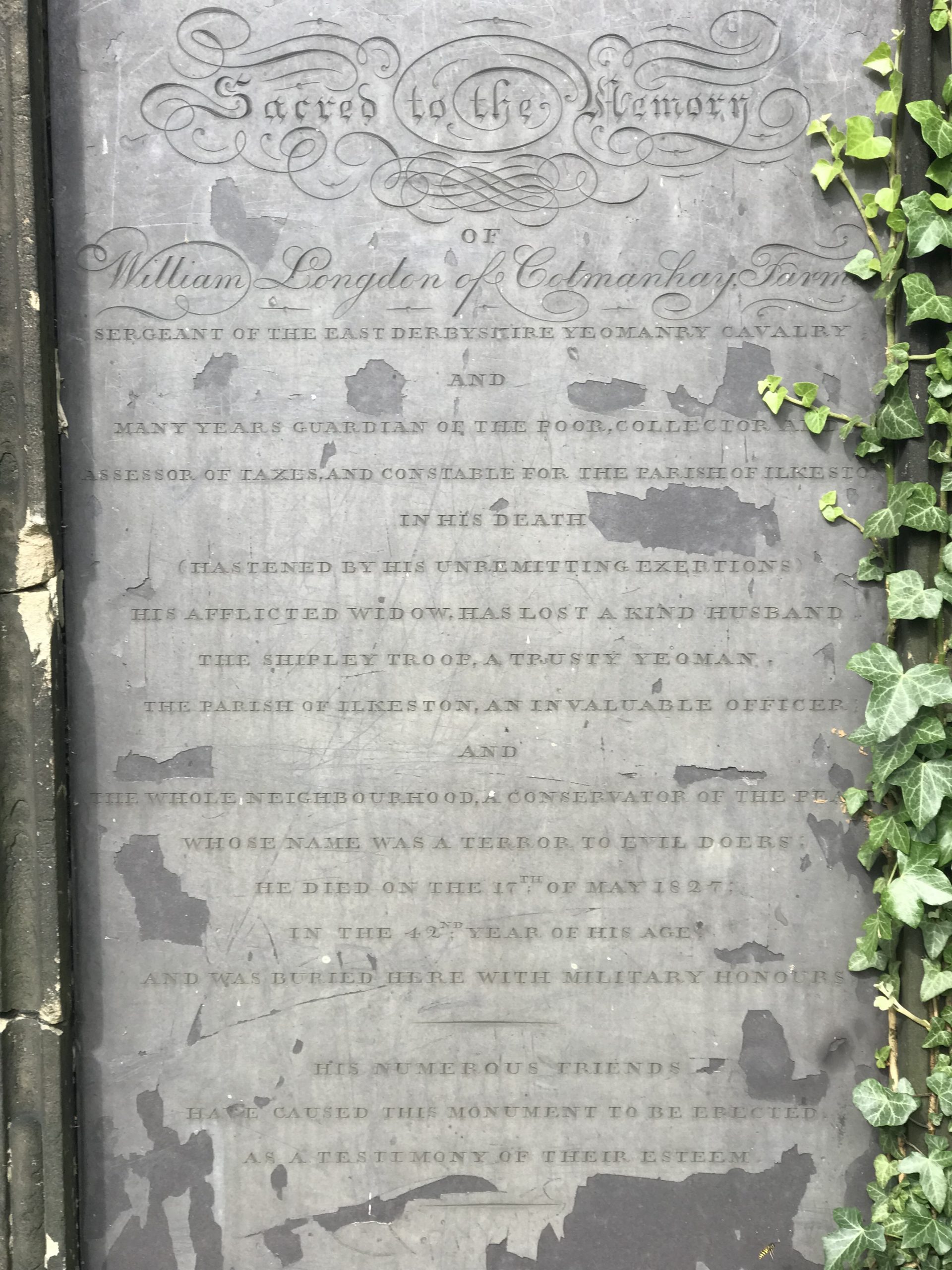

Another terror of evil-doers: William Longdon (c1786-1827)

William was a predecessor of George Small as a ‘terror of evil-doers’. Trueman and Marston (1899) write that when he died in 1827 “a troop of the East Derbyshire Yeoman Cavalry .. followed him to the grave, as also did his horse withits late master’s uniform on its back, and large crowds of his fellow townsmen. His hat and gun were placed on the coffin: and several volleys were fired over the grave“. The monument (below) is described as standing about eight feet high, consisting mainly of stone, with four slate panels. The two writers go on to point out that it was repaired by a public subscription initiated by Joseph Shorthose in 1888.

Sacred to the Memory

of

William Longdon of Cotmanhay, Farmer,

SERGEANT OF THE EAST DERBYSHIRE YEOMAN CAVALRY

AND

MANY YEARS GUARDIAN OF THE POOR, COLLECTOR AND

ASSESSOR OF TAXES AND CONSTABLE FOR THE PARISH OF ILKESTON.

IN HIS DEATH

(HASTENED BY HIS UNREMITTING EXERTIONS)

HIS AFFLICTED WIDOW HAS LOST A KIND HUSBAND

THE SHIPLEY TROOP A TRUSTY YEOMAN,

THE PARISH OF ILKESTON, AN INVALUABLE OFFICER,

AND

THE WHOLE NEIGHBOURHOOD A CONSERVATOR OF THE PEACE,

WHOSE NAME WAS A TERROR TO EVIL-DOERS:

HE DIED ON THE 17TH MAY 1827:

IN THE 42ND YEAR OF HIS AGE

AND WAS BURIED HERE WITH MILITARY HONOURS

———

HIS NUMEROUS FRIENDS

HAVE CAUSED THIS MONUMENT TO BE ERECTED

AS A TESTIMONY OF THEIR ESTEEM.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

So let’s now look at the case of Selina Sudbury, a ‘not so evil-doer’, mentioned above, before moving into East Street.