and not far from Ebenezer Chapel, we come to …..

Ilkeston Pottery

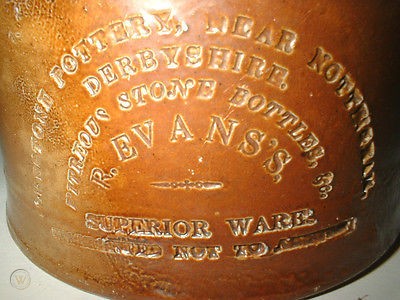

Producing mainly stoneware bottles, Ilkeston Pottery had been established in 1807 by Richard Evan’s father, George, pot-maker of Belper, though 1809 is when there is evidence of George in Ilkeston. In that year he acquired land on the east side of the Erewash Canal, just south of Coal Pit Lane (now Awsworth Road), from framework knitter Thomas Potter in 1809. On it he built a house and pottery works, living there with his wife and children.

In July 1805 George had married Mary Hives, aunt to Thomas Hives of the Rutland Hotel.

The father was aided in the business by his son, Richard, and when the former died in May 1835, Richard and his elder brother George junior continued the trade.

Later in the same year (December 7th, 1835) Richard married Elizabeth Floyd, daughter of Charles and Elizabeth (nee Sheldon) of Newhall, Derbyyshire, at St. Mary’s Church, Ilkeston. As the Nottingham and Newark Mercury described (December 12th, 1835) this was after a whirlwind courtship lasting 14 days and while Elizabeth was visiting Ilkeston Baths.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

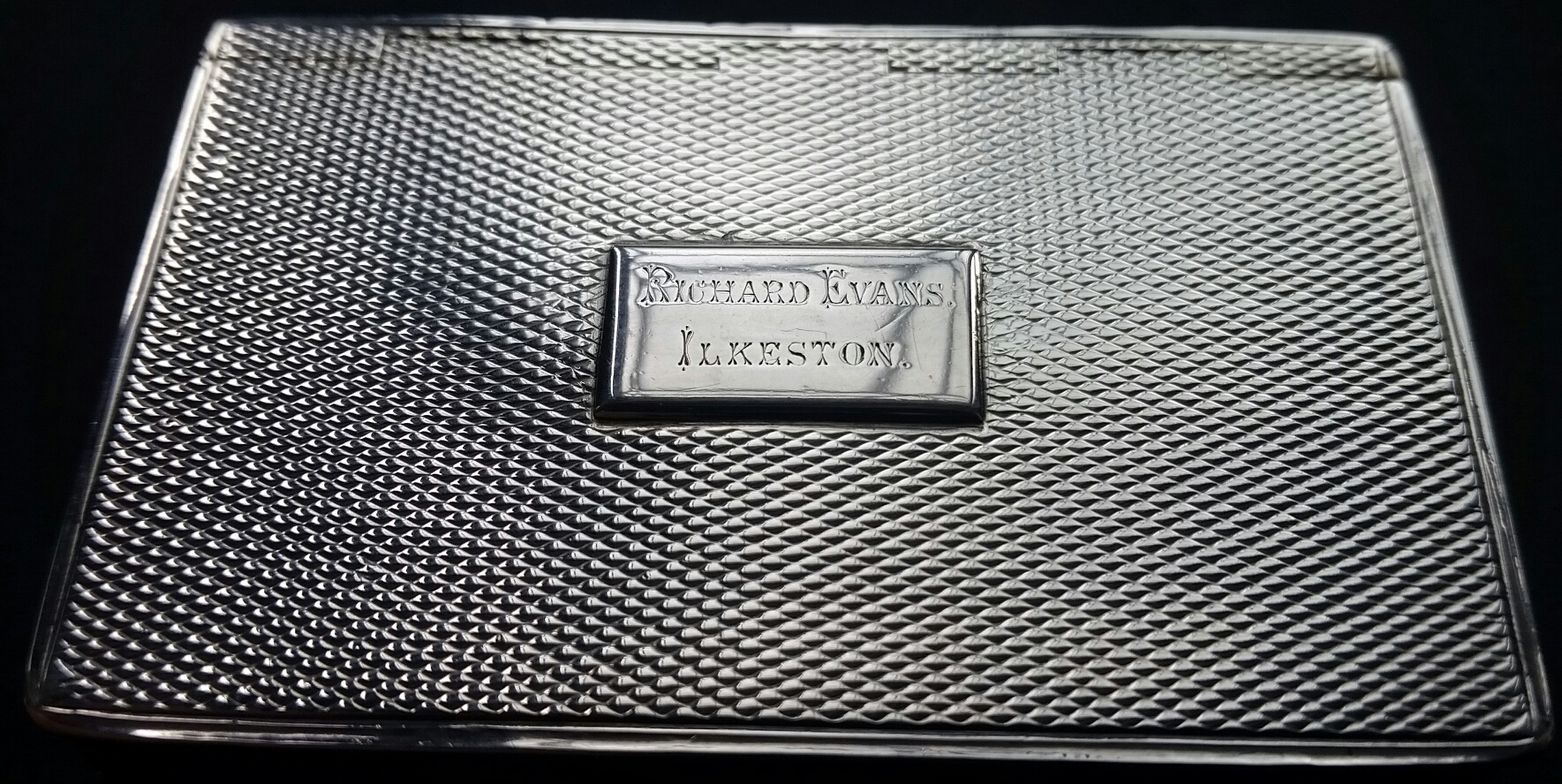

Courtesy of the Andrew Knighton collection… images of Richard Evans’ snuff box.

.Andrew adds …. I bought it at a fine art auction in Nottingham in the mid-1980s but unfortunately no provenance was given in the catalogue. However, I have no doubt the Richard Evans inscribed on the tablet is the same Richard Evans of Ilkeston Pottery. It is hallmarked 1835 and so would have been sold that year or shortly after. It’s in the form of a leather bound book and has a gilt interior (but was virtually black from old snuff when I bought it). To give an idea of size, it’s 2.75 inches in length

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

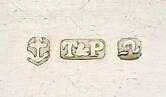

This magnified picture of the hallmark shows an anchor, the letters T&P followed by what looks like an N. From this you can discover where the snuff box was made, who made it and when. The year of manufacture followed a significant one in Richard’s life !! … was it a belated gift from a friend or relative ??

As the area developed, it was referred to as ‘Pottery’ or ‘The Potteries, or ‘Canal Side’, with its own row of ‘Evans Cottages’ — sometimes referred to as ‘Evans Row’ though not to be confused with the yard of the same name at White Lion Square — and ‘Evans Shops’ (or workshops?).

And just south of the Pottery Richard laid out his ornamental gardens with glasshouses and fish ponds, the whole of which an ‘Old Resident ‘ (1917) recalls were “one of the sights of the town”.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

Employer Richard

The same writer described Richard as “an aristocratic-looking man, with a rubicund countenance, and of good appearance, who was never known to wear any other headgear than a tall, stylish white hat, with a fairly broad black band.

He was usually referred to by those who knew him well as ‘Honest Dick’. He enjoyed the distinction of being the only man in the town to drive in his carriage, (with Mrs. Evans and a lady companion) to service at St. Mary’s Church on Sunday evenings, where he attended very regularly”.

Giving evidence to the Children’s Employment Commission of 1842, Richard Evans declared that he employed two children under 13 and four young people under 18.

The children worked from 9am to 7pm, and were allowed one hour to go home for dinner, and half an hour for tea, on the premises. The young people worked from 6am to 6pm, with half an hour for breakfast and one hour for dinner.

He had seen no effect on the children’s health caused by their work, which was either turning the potter’s wheel or forming clay balls, to be later made into bottles.

He was attentive to their morals and allowed no swearing or wickedness at the works.

Most of the children attended the Sunday-schools and some an evening school.

How effective this schooling was, might be gauged by the evidence of Esther Ann Eley, aged 8, who turned a potter’s wheel and had been to school in Cotmanhay where ‘they ne’er taught her aught’.

Certainly not to write her name — at each of her three marriages, in 1848, 1851 and 1865, she made her mark on the register entry.

William Farnsworth, aged 15, did the same type of work as Esther Ann, had been to Sunday-school for about five years and had been taught to read (indifferently) but ‘they did not teach writing at the schools’.

His brother, Frederick Farnsworth, aged 8, had been to a school for four years but now attended only a Sunday-school. His education had also enabled him to read ‘the Testament’ but not to write. Perhaps Frederick’s motivation for academic achievement was questionable…he admitted enjoying his work of making clay balls better than school.

The Farnsworths lived at Evans Row, at the north end of what is now Stanton Road, before moving to ‘Pottery’.

Prior to arriving in Ilkeston, the Farnsworths travelled from Gibraltar (where William was born) to Guernsey (the birth place of Frederick) while their father John was serving in the Royal Artillery. Born about 1798 he had enlisted at the age of 17, had served for almost 25 years and left in 1840 with three Badges of Distinction for good conduct, rheumatism and bad case of asthma.

In 1843 the Evans brothers divided their business.

Richard now made stone bottles only, while George was responsible for the earthenware manufacturing side.

In May 1847 the partnership between Richard Evans and John Lowe Smith of Ilkeston, stone-bottle and brick and tile manufacturers, was dissolved.

Brother George Evans seems to have moved premises in the 1850’s and the 1855 Post Office Directory shows George, in Chapel Street, as does the 1861 census. And around this time he is variously described as “shopkeeper, beer retailer, chimney, sea-kale and garden pot manufacturer, maker of sanitary pipes and border tiles”. (Was he at the Flower Pot beerhouse?)

Andrew Knighton has very kindly sent in images of items made at Ilkeston Pottery at this time. He writes … I have a salt glazed stoneware inkwell made by Amos Potter. Underneath you will see it has been inscribed ‘Amos Potter / Ilkeston / August 2nd 1845’.

Born in 1824, Amos Potter was the son of John and Hannah (nee Street) and by the time of the 1841 census both his parents were dead. On that census Amos is residing with Richard Evans at ‘Pottery’ as a male servant, as is his brother John. You will not find Amos on the 1851 census …. he died on December 27th 1850, when he was described as a ‘traveller for Richard Evans’.

………………………………………………………

I also have a puzzle jug (right) inscribed underneath ‘W Hibbert / maker / Ilkeston’ which is also almost certainly an Ilkeston Pottery product too.

It is dated August 2nd 1852 as part of the inscription; ironically exactly 7 years after Amos made the inkwell.

Puzzle jugs were very popular in the early Victorian era and the trick was to drink out of the jug without spilling any liquid.

Not easy until you realise that you have to cover all but one of the spouts and also cover the very tiny hole under the top part of the handle to be able to suck through the remaining spout.

…………………………………………………….

And here are a few more examples which I found online.

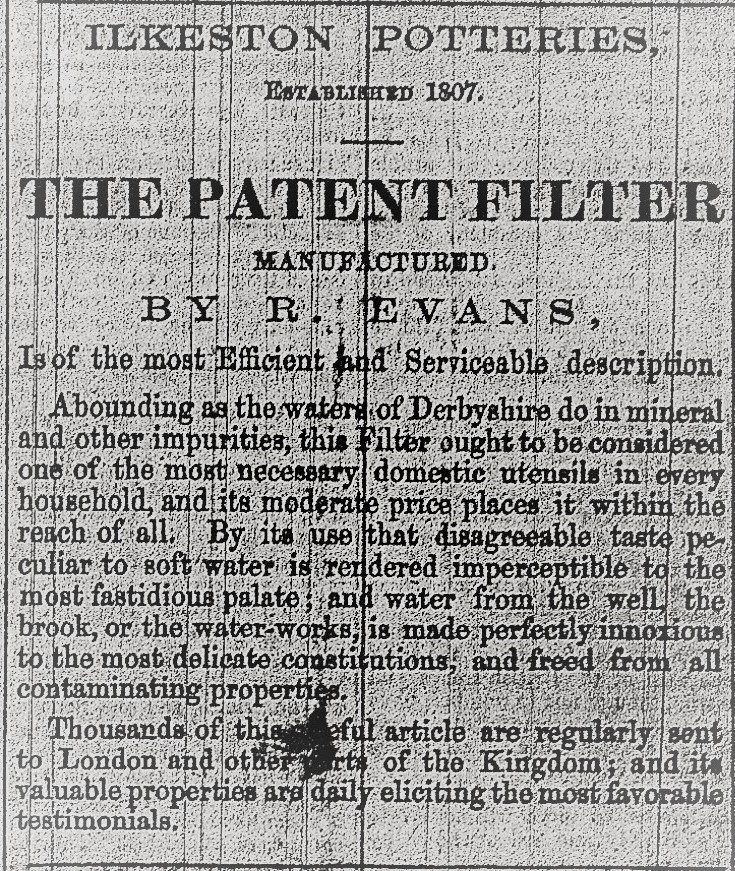

And ever the improver … a new product from Richard, as advertised in the Ilkeston News (Oct 10th 1857)

At the beginning of 1858 Richard had just completed ‘very extensive alterations‘ to his premises, introducing the ‘most approved machinery, by hand or steam-power’, leading him to offer lower prices than any competitor and improved quality and durability. Now also, he had just added the manufacture of Terra Cotta goods of every sort: ‘ground indicators, grave, space and section markers’. Stoneware sanitary pipes, water closet pans, sink traps, water filters, fancy vases, vitreous jars and bottles, border tiles and fire bricks, etc., etc., were still available of course, at Ilkeston Potteries, established 1807.

Also in 1858, Richard was present at Smalley Petty Sessions when Sarah Bramley (nee Baker), and her 12-year-old daughter Mary – one of Richard’s workers — were charged with stealing articles of earthenware from the Pottery, articles which Sarah maintained had been given to her daughter ‘as wasters’.

The ‘theft’ came to light when Mary had taken an inkstand from the Potteries to her grandaunt Ann Holmes (nee Wright) who lived next door to her. The grandaunt advised the child to return it …which she did.

Other ‘stray’ items were then found in the Bramley home and the subsequent court case was not going well for mother and child until Richard intervened.

He spoke on behalf of Mary, thinking that she had been led into her crime by her mother, against whom he thought there was not sufficient evidence. He therefore requested the charges be withdrawn rather than see Mary punished — a request which the magistrates allowed — but not before severely chastising Sarah.

She was advised to thank Richard for his kindness.

It seems however that she was not impressed and showed little gratitude.

At the same Petty Sessions, while the magistrates were hearing this and other cases, one member of the attending public was unknowingly relieved of £3, despite the presence of several police constables.

The Justice Rooms were packed at the time and suspicion later fell on some ‘smiling and well-known rogues’ who were free to spectate like anyone else.

Only a few months earlier these same rogues had been found guilty of felony in the same court and were fined.

Perhaps they were trying to reclaim their fine?

In 1862 a pregnant ‘poor woman named Jarvis’ was helping her son at the Pottery.

She needed to rest at the top of steps up which she had just carried a ball of clay when her dress caught in machinery.

Steam-powered wheels entangled her with fatal consequences.

The resulting inquest blamed no-one, recorded a verdict of accidental death but suggested proper guards to the machinery should be installed, a recommendation duly adopted by the owner.

Richard also bore the costs of the resulting funeral.

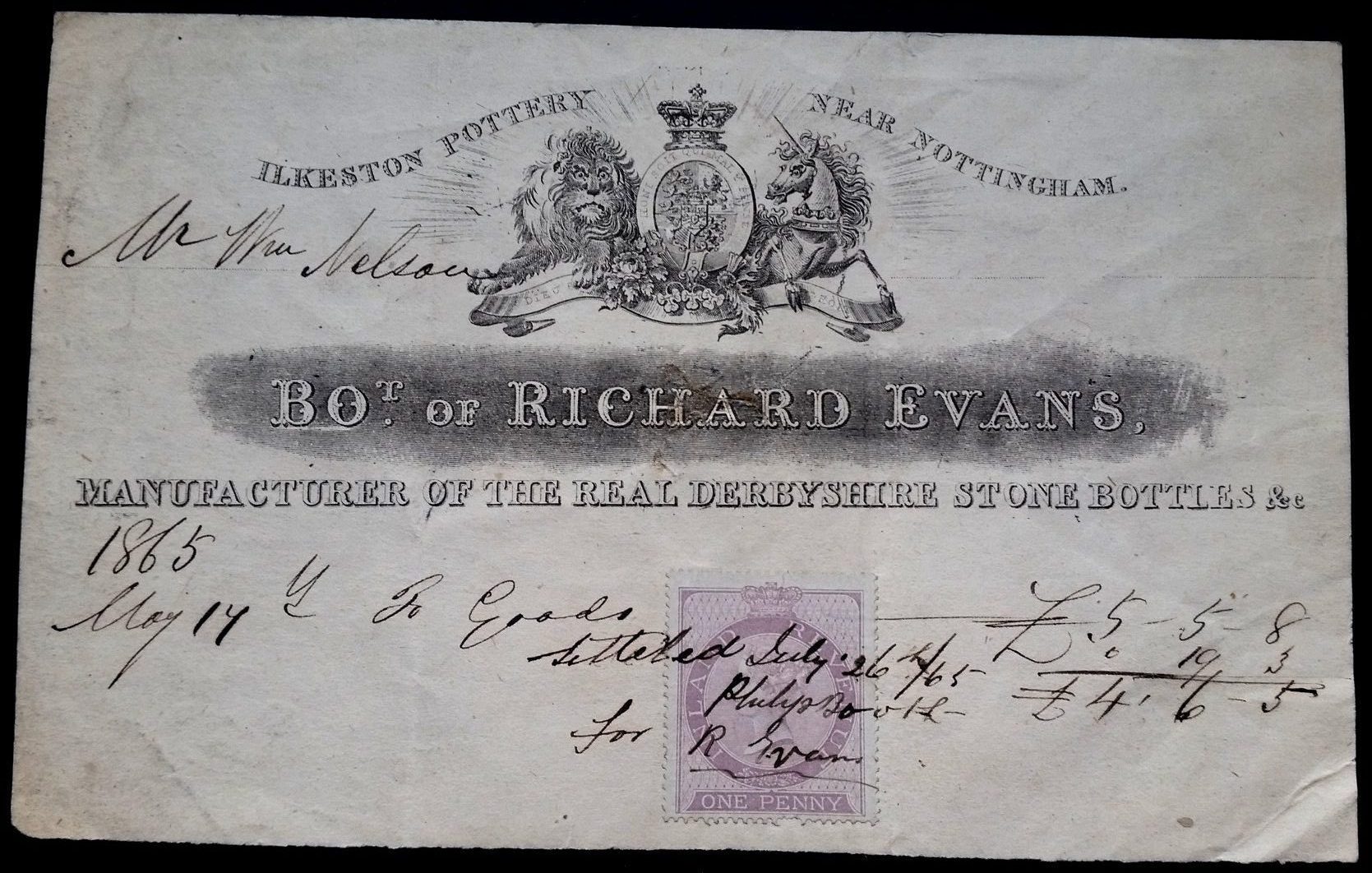

A billhead for Ilkeston Pottery, 1865 ( from Andrew Knighton)

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

Homeowner Richard

In 1864 Richard undertook some internal improvements at his home when he decided to have encaustic tiles laid in his hall and passage.

He was quoted a price for the work by builder Isaac Warner which was accepted.

The tiles were ordered and delivered, but when Isaac eventually turned up to do the job he was told that his services were no longer required. Richard was moving to Beeston and the ‘makeover’ was thus cancelled.

Understandably Isaac was peeved especially when Richard refused to pay for the redundant tiles.

Isaac sued the potter at Belper County Court for their cost. However the ‘facts’ of the case were clouded when Richard declared that he had not cancelled the job at all but had questioned the initial estimated price of the work compared with the final quote. He was also unhappy about the length of time it was taking Isaac to start the improvements and his testimony, and that of his wife and niece, seem to have been persuasive.

The Judge decided in his favour.

It appears that in late 1864 Richard did depart for Beeston but the move was not permanent.

On a Saturday morning in August 1875 heavy thunderstorms and torrential rain, ‘unprecedented since 1830’, swept along the Erewash Valley (and throughout the East Midlands and into Yorkshire).

Low lying as it was, Richard’s house was soon several feet under flood water with his gardens entirely covered.

The ground floors of houses in the nearby Potteries were uninhabitable while their occupants escaped into the bedrooms, at times accompanied by their family pigs.

Haystacks in adjacent meadows were destroyed and sheep, lambs, pigs and at least one horse were lost in the area up towards Twells Field on the east side of lower Bath Street.

At the Rutland Arms, Bath Street was converted into a river, while across the road and down Slack Lane (Rutland Street), the work at Adlington’s steam corn mills was brought to a halt — the water rushed in and extinguished the fires there.

Traffic at Ilkeston Junction station at the bottom of Station Road was interrupted as earth beneath the lines was washed away.

Spouts on St. Mary’s church tower could not release the rain water sufficiently quickly enough and it burst down the steps to the tower’s base ‘like a weir’.

Thousands of bricks in the drying sheds at Gallows Inn brickyard were lying under water all day and ‘were again converted into shapeless clay’. Flood waters rose sufficiently high as to extinguish the blast furnace fires at the Bennerley and Erewash Valley Iron Companies.

By Monday the floods had almost completely disappeared.

In August 1876, “with his usual thoughtfulness and liberality” Richard donated a beautiful hand-bell to the parish Sunday-schools. (IP)

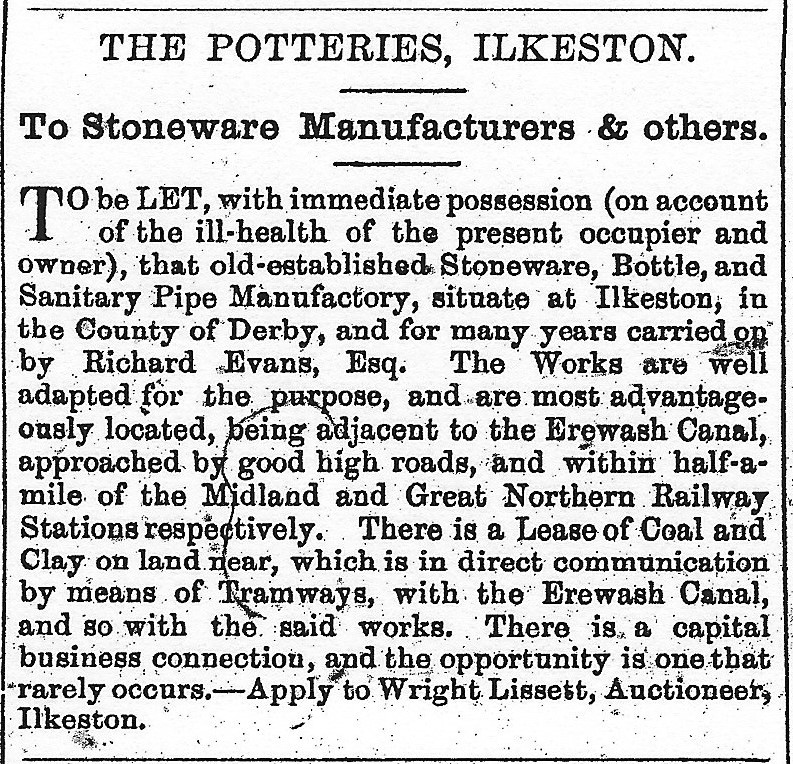

In June 1879 ill health forced Richard to put up the Potteries for let.

The pottery had closed by 1880 when Richard retired.

His gardens and greenhouses adjoined the row of Pottery cottages and in late January 1881 one of these cottages, thankfully unoccupied, was set on fire through the over-heating of a flue in one of the greenhouses. Several men rushed to the spot, broke the ice over the canal to gain access to the water and the fire was quickly contained, gutting only the first cottage.

Richard died at Brook House at the Potteries on June 21st, 1887, aged 77.

His widow Elizabeth continued to live at the Potteries and died at the same house on March 20th, 1895, aged 81. Almost exactly a year after Elizabeth’s death, parts of the Evans Estate were put up for auction. These included six houses (61-65) in Awsworth Road; several houses and some garden ground in Ebenezer Street (numbers 59-68, 33-38); all 18 houses in Nesfield Terrace; Babbington Cottage and an adjacent piece of land named as Dayfore (Day Gore?) Close, previously used as a coal wharf, which was on the north side of Station Road and fronted onto the west side of the Erewash Canal — part of it had been used by brickmakers Messrs Beardsley and Pounder; the ten houses in Grove Terrace, also known as The Grove, on the south side of Station Road, with a frontage to the east side of the Erewash Canal; several other houses and land, also at the side of the Erewash Canal and to the south of Grove Terrace, in the area known as ‘Spicer (Spicey) Meadow’.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

Brother George Evans (1808-1870) …

Richard’s elder brother George had married Diana Shaw, daughter of collier John and Hannah (nee Jackson) on October 14th, 1828.

Unlike Richard and his wife who were childless, George and Diana had at least six children.

Also born to Diana in October 1827 was her illegitimate son, John Evans Shaw alias John Evans, also later a pot maker.

After the death of George in 1870, John lived briefly with his mother and his wife, Ann (nee Musson) at 60 Awsworth Road.

He died in April 1871.

Diana died at the Awsworth Road home in 1887.

The gravestone of George and Diana can be found standing by the south wall of the main churchyard of St. Mary’s, with this inscription: –

In loving memory of George Evans who died Dec 28th 1870, aged 63 years

Also Diana his wife who died Sep 8th 1885, aged 77 years

Also Martha their daughter who died Feb 13th 1889, aged 60 years.

It was about 18 months later that property in the estate of George was auctioned off by his grandson Arthur Behrens, son of Isaac and Harriet (nee Evans). There were several pieces of freehold property — ‘Rose Cottage’ in Awsworth Road, and a house next door, with orchard and gardens; three properties in Station Road; and the six houses in Chapel Street Row, off Chapel Street. There were also four copyhold cottages in Chapel Street and a copyhold piece of undeveloped land in the same area. With the exception of the three Station Road houses, all were bought by Joshua Harrison Bates, tailor and hairdressser of Awsworth Raod and the son-in-law of the late George Evans, being married to the latter’s daughter Elizabeth, in 1864.

… and brother John (1806-1884)

Richard and George had an older brother John, born at Belper in 1806, who married Alice Blount, daughter of West Hallam-born Joseph and Sarah (nee Musson) in October 1827.

He appears as a potter and bottle maker, then boatman, and later as a contractor, living nearly all his life at the Pottery.

He died at Canal Side in October 1884, aged 78, three years after his wife.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

Most of the Evans family are buried in the churchyard of St. Mary’s.

In 1899 Ilkeston Laundry was established on the site of Ilkeston Pottery before the premises were demolished in 1913. The laundry lasted until the Second World War.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

The Potteries in 1891

Examining the Potteries, at the side of the Erewash Canal, on the 1891 census, you will find a group of 24 cottages, about half a dozen of them uninhabited. (It was also known as Canal Side)

In number 17 lived coalminer widower Henry Potter, whose wife, Harriet (nee Smith), had died there in `1884, aged 38. He worked at a local pit , earning about £2 a week, most of which (it was alleged) was spent on drink and dog-racing.

In November 1891 Henry found himself facing the authority of the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children at Ilkeston Petty Sessions, charged with brutal neglect of his two youngest children — Alice, aged 12, and Mary, aged 10 — and thus causing them unnecessary suffering. Also in the family was another daughter, Ellen, aged 16, almost blind.

Alerted by Miss Brant, headmistress of Granby Girls’ School, the house was visited by Sergeant Stanley of the local constabulary. His search revealed only one bed with no bed-clothes, which the father and his daughters all used together. The children’s clothing was nothing but rags, they were covered with sores and vermin and the bedroom was covered with human exceta and filth. He discovered only one crust of bread for food in the whole house which stank abominably and contained hardly any furniture — just an old sofa, three filthy chairs, a small tin saucepan, a small tea kettle, two filthy plates, two teaspoons and one knife. In one small room there was a great heap of ashes, used as a toilet. The children washed in an old iron pot, also used for washing-up, and with no towel. Nor was there any change of clothes for the children ….. no other clothes at all save for the father’s ‘spare suit’.

Henry argued that the sheets had been sent for washing when the police visited; and that he would get married and ‘have things altered’ !! For his neglect, the coalminer was sentenced to one month with hard labour, plus two weeks of the same if he failed to pay 18s costs.

The case might be compared with that of Annice Wigley and her children, at the toll bar in White Lion Square, over 30 years earlier.

Later events about the Potter family …

It would appear that father Henry didn’t marry again to ‘get things sorted’ And he remained at 17 Canal Side at least for another 20 years. I believe he died in Ilkeston in 1923, aged 78.

His oldest child, not mentioned above, was William Smith Potter, an illegitimate child, born about 1865, in Radford, Nottingham, who had already left the Potteries home by 1891 — he married Anne Trueman in 1889, worked as a coalminer in Cossall for a short time, but then returned to the Potteries. He died in 1928 (I believe)

Born in 1868, daughter Susan had also left home, after her marriage to Isaac Henshaw in 1890. Two of their five children died in infancy; the other three were left as orphans by 1899 — Susan died in October 1898, and Isaac in October 1899.

Son Henry, born in 1871, married Mary Barks in 1891, then lived in Awsworth Road, working as a coalminer.

Born in 1873, Annie Potter married Awsworth coalminer Thomas Winfield in 1890 and thereafter lived in his home village.

Of the three unfortunate daughters in the family story, Ellen married John Walter Parsons in 1896, Alice married coalminer Edward White of Awsworth in 1900, and Mary married another coalminer, Arthur Chapman, in 1901.

Some of this detail hasn’t been sufficiently verified — so if anyone can add support or rectify mistakes, I would be very grateful. And I can’t comment upon how the lives of the unfortunate daughters were improved or not, after they had left the Potteries and their father.

This case was almost identical to the one that was uncovered, at the same time, at 8 Critchley Street where shoemaker Charles Frederick Pollard lived with his wife and eight children, four of whom were described as ‘neglected in such a manner as to cause them unnecessary suffering and injury to their health’.

In this instance the mother Fanny Maria (nee Beardsley) found herself justifiably blamed by the Court, such that she was sent to jail for a month with hard labour. The shoemaker husband was discharged with no blame — we have come across him before, remember ?

It seems that the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children had its hands full, dealing with Ilkeston cases at this time. This was, in large part, a consequence of the passing of the Prevention of Cruelty to, and Protection of, Children Act of 1889, commonly referred to as the Children’s Charter, the first Act of its kind. Often the cause of neglect was put down to ‘drink’ (as in the case of the Pollard children)

A dangerous place

The location of the Potteries, by the nature of the trade pursued there, was very precarious and at times fatal.

Approaching Christmas of 1894, Ann Oakes, aged 59, lived there with her husband Thomas. During a Saturday night shrouded with dense fog, she left her canal-side home to visit her daughter Mary and her son-in-law William Walker Trueman, who lived close by, in Chapel Street. She had tea there and then left for her home about quarter to six. As she left, William warned her to go round by Awsworth Road rather than down Blake Street, and so avoid the canal side, on account of the fog. Ann concurred. She was never seen again alive, her dead body being found floating face down in the Erewash Canal, between the railway and canal bridges opposite the night-soil depot, the following Sunday morning.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

And finally we take a walk to the tow path of the Erewash Canal to meet the Dawson family.