A brief background to Education in the Victorian Age

In the first years of the Victorian Age education was not compulsory, nor was it free. The state took no part in providing it.

Obviously therefore, rich families could afford the education they thought necessary for their children; poor folk would more than likely want their children to go out to work as soon as possible. Some schooling was available for poorer children — like Dame Schools, and Common Day Schools for older scholars. And as we have just seen, Church or Charity schools were available for a few children and for a few pence — like the Butter Market School.

The revolution in Britain’s industry and society in the mid and late Victorian era, coupled with the great growth in population, changed many people’s perception of the need for educationai provision. The Established Church struggled to keep up with these changes by providing more of its National Schools while Nonconformists countered them by building their own British Schools.

Increasingly the central Government realised that it would need to take a more active role. In 1870 the Balfour Education Act was passed, and School Boards were introduced to facilitate the growth/building of schools, and thus more education, in areas where this was felt necessary — like Ilkeston !! Despite the efforts of Ilkeston’s Church authorities to resist the establishment of a School Board, they had to admit defeat in 1878. And from that year until the end of the Victorian Age, many so-called Board Schools were built in the town — starting with Granby Schools.

All of these developments will be outlined in this section.

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

Church Schools versus Non-conformist Schools

How did Church Schools fit into the Education system of early Victorian Ilkeston ?

It might be true to say that most people in Ilkeston in 1800 were illiterate.

At that time central government saw no role in providing education and so there was no national system of education.

Educational opportunity varied enormously and depended on class, location, gender and wealth.

Subsequent development in education came piecemeal and was hampered by religious rivalry and short-sighted employers.

From about 1810 churches and charities became more actively involved in providing elementary education for the poor.

Founded in 1808 and primarily supported by non-conformists, the British and Foreign Schools Society was providing elementary education in their ‘British Schools’ — a mere 1500 of them in 1851 … one of which was in Bath Street, Ilkeston.

The Anglican National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church (or S.P.C.K) founded in 1811, built so-called ‘National Schools’ – of which there were 17,000 by 1851.

Both Societies were concerned more with an improvement in morals than with a general education. And the two of them were in severe conflict and competition for most of the century.

This rivalry bedevilled progress in education.

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

Signs of surreptitious socialism ?; the Government sticks its nose in

By the early 1830’s the Government had recognised that it had some part to play and from 1833 made a grant of £20,000, shared by the two societies for the building of their schools.

The Committee of Council on Education was created in 1839 to oversee this grant which was increased to £30,000 and to £100,000 by 1847.

Inspectors were appointed; clergymen for the Church of England ‘National’ schools, and laymen for the Nonconformist ‘British’ schools.

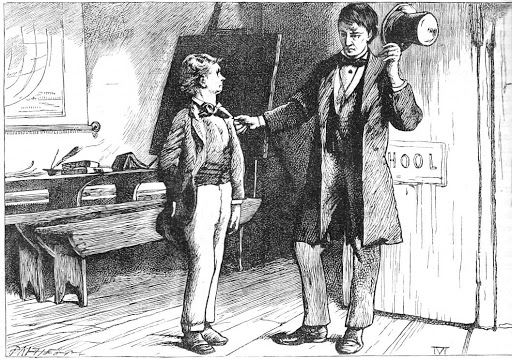

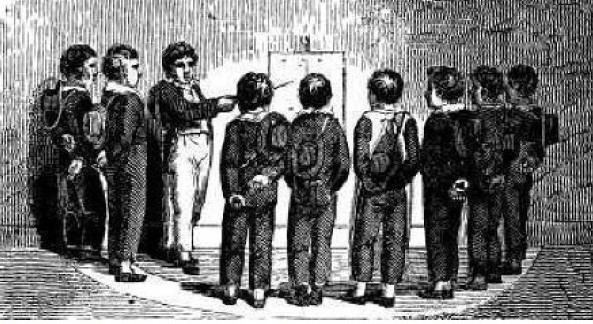

Schools receiving a government grant had to use the monitorial system of teaching. This meant that a teacher would select a few older ‘monitor’ students — aged about 10-12 years old — and give these monitors simple instructions which they passed on to groups of pupils.

Monitors receiving their ‘simple instructions’

Monitors receiving their ‘simple instructions’

Work was learned by repetition and the teacher was there as supervisor, examiner and disciplinarian.

The system was incredibly economical with as many as 500 under one teacher. However its factory-like system mistook acquisition of facts for knowledge, and was not suitable to accommodate individual rates of learning. Consequently it was eventually recognised as inadequate and was replaced, starting in 1846, by the pupil teacher apprenticeship scheme which was to be the main source of teachers for the rest of the century. Pupil teachers were appointed for a five-year period at the age of 13, were paid a small salary and were coached by a certificated teacher for about an hour and a half each day, after school. They were examined annually by Government Inspectors. At the age of 18 they sat for a “Queen’s Scholarship” and, if successful, they could go on to a training college for a maximum of three years to qualify as certified teachers. The colleges, of course, were privately owned by the Church … that is, until 1870 and the passing of Forster’s Education Act. The latter then allowed any ‘School Board’ to set up its own publicly-financed pupil-teacher centres where intending teachers were instructed at evening classes — during the day they acted as ‘cheap labour‘ assistants at the Board’s schools !!!

By 1857 the government grant had increased to £500,000, and to administer this a Department of Education was set up.

Monitors did not die out completely thereafter but could be used in concert with pupil teachers.

In 1862, just prior to leaving school at the age of ten, Old Resident was appointed as a monitor at Ilkeston’s National School, being paid 1s 2d per week, out of which 2d was deducted as his ‘school wage’.

At that time Alfred Fletcher and Smith Potts were pupil teachers at the school.

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

Charles Dickens (1812-1870) was a supporter of ‘comprehensive liberal education’. He held firm views on many aspects of contemporary developments in education, such as church involvement, inspection of schools, teaching methods, and, as he saw it, the disadvantages of teacher training.

One product of the pupil teacher system was Mr. M’Choakumchild, who appears briefly in ‘Hard Times’, at the school of Thomas Gradgrind, where children are regarded as little ‘pitchers’ waiting to be filled with facts and numbers.

“(Mr. M’Choakumchild) and some one hundred and forty other schoolmasters, had been lately turned at the same time, in the same factory, on the same principles, like so many pianoforte legs. He had been put through an immense variety of paces, and had answered volumes of head-breaking questions. Orthography, etymology, syntax, and prosody, biography, astronomy, geography, and general cosmography, the sciences of compound proportion, algebra, land-surveying and levelling, vocal music, and drawing from models, were all at the ends of his ten chilled fingers. He had worked his stony way into Her Majesty’s most Honourable Privy Council’s Schedule B, and had taken the bloom off the higher branches of mathematics and physical science, French, German, Latin, and Greek. He knew all about all the Water Sheds of all the world (whatever they are), and all the histories of all the peoples, and all the names of all the rivers and mountains, and all the productions, manners, and customs of all the countries, and all their boundaries and bearings on the two and thirty points of the compass. Ah, rather overdone, M’Choakumchild. If he had only learnt a little less, how infinitely better he might have taught much more! “

And here is ‘highly certificated stipendiary schoolmaster’ Bradley Headstone of Dickens’ ‘Our Mutual Friend’ —

“He had acquired mechanically a great store of teacher’s knowledge. He could do mental arithmetic mechanically, sing at sight mechanically, blow various wind instruments mechanically, even play the great church organ mechanically. From his early childhood up, his mind had been a place of mechanical stowage. The arrangement of his wholesale warehouse, so that it might be always ready to meet the demands of retail dealers history here, geography there, astronomy to the right, political economy to the left—natural history, the physical sciences, figures, music, the lower mathematics, and what not, all in their several places—this care had imparted to his countenance a look of care; while the habit of questioning and being questioned had given him a suspicious manner, or a manner that would be better described as one of lying in wait.

There was a kind of settled trouble in the face. It was the face belonging to a naturally slow or inattentive intellect that had toiled hard to get what it had won, and that had to hold it now that it was gotten. He always seemed to be uneasy lest anything should be missing from his mental warehouse, and taking stock to assure himself”.

————————————————————————————————————————————————–

and let’s now cast a glance at the rival to the Church School in the Market Place …. The British School in Bath Street)