After the Rutland Arms … Adeline recalls that “at the bottom of Bath Street on the West side we come to Manor Road, in which was the Manor House.” And here we meet two very distinguished families bound together by marriage.

The site of the Manor House on the Local Board Map 1866

The Cockers and Taylors

The Manor house was also known as Ilkeston Hall.

The south western corner of the Manor House in the last year of its life … 1960

The Cocker family

The Cockers came from Heanor about 1634 when nailer Richard Cocker bought a farm in Ilkeston from William and Eleanor Marshall, according to Trueman and Marston. For some years the family made little impression on Ilkeston.

In 1658 George Cocker had an Ilkeston mill by the river Erewash.

The family later occupied the Manor House and had strong connections to the Unitarian Church in High Street.

A son of John Cocker and Hannah (nee Dovrale?), Isaac Cocker died on February 17th 1849, aged 68, at Ilkeston Hall. He is identified by Trueman and Marston as “the last representative of the family at Ilkeston”.

On the day of his burial, Shrove Tuesday, a performance of the ‘Messiah’ was held at the South Street Wesleyan Chapel as recalled by “Kensington”.

“Henry Farmer* conducted, and he was ably supported by George West, John Richardson, and an army of Goddards, Adcocks, Tilsons, Harrisons, Carriers, and others”.

*Henry Farmer (1819-1891) was an organist, composer and ‘Professor of Music’, born in Lenton, Nottingham … he has his own short Wikipedia page.

In his will, a very prosperous Isaac left most of his estate, including property, to his nephew John Taylor, the son of John Taylor senior and Hannah (nee Cocker), Isaac’s sister.

In addition he made bequests of £400 to each of his nieces, the daughters of John senior and Hannah Taylor — that is, spinster Mary; Sarah Parkinson (wife of Joseph Parkinson, a farmer at Wisthorpe near Sawley); Eliza Fletcher (wife of Mapperley farmer John Fletcher); Hannah Hobson (wife of Matthew Hobson); Martha Grammer (wife of Thomas Grammer, farmer of Greasley Castle in Nottinghamshire); Frances Toule (wife of Jonathan Toule, farmer of Watnall, Nottinghamshire); and spinster Jane. In a codicil to the will, added five years later, Isaac bequeathed to still spinsters Mary and Jane any furniture, glass, linen, bedding, china and plate as they wished to take; the rest of his similar effects were to be divided equally between his other married nieces and his nephew.

Mary Taylor also received an additional annuity of £20, payable to her, by her brother John, every six months for the rest of her life…. was she Isaac’s favourite ??

If for any reason nephew John Taylor was unable or unwilling to take over the Cocker farm, then it would pass to Martha Grammer.

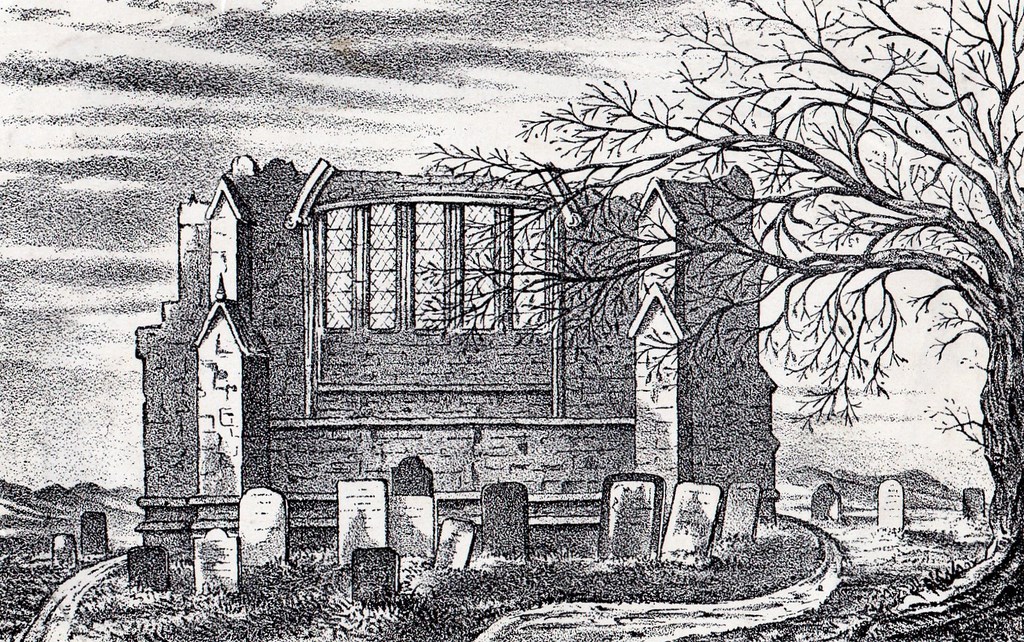

The Cockers have their family burial section in St. Mary’s Churchyard, at the east end of the Church.

Above, the Cocker memorials at the east end of St. Mary’s Church in 1840.

And below, their memorials in 2022, though there are a couple more in the main graveyard

The Taylor family

A brief helpful (?) early family history ….

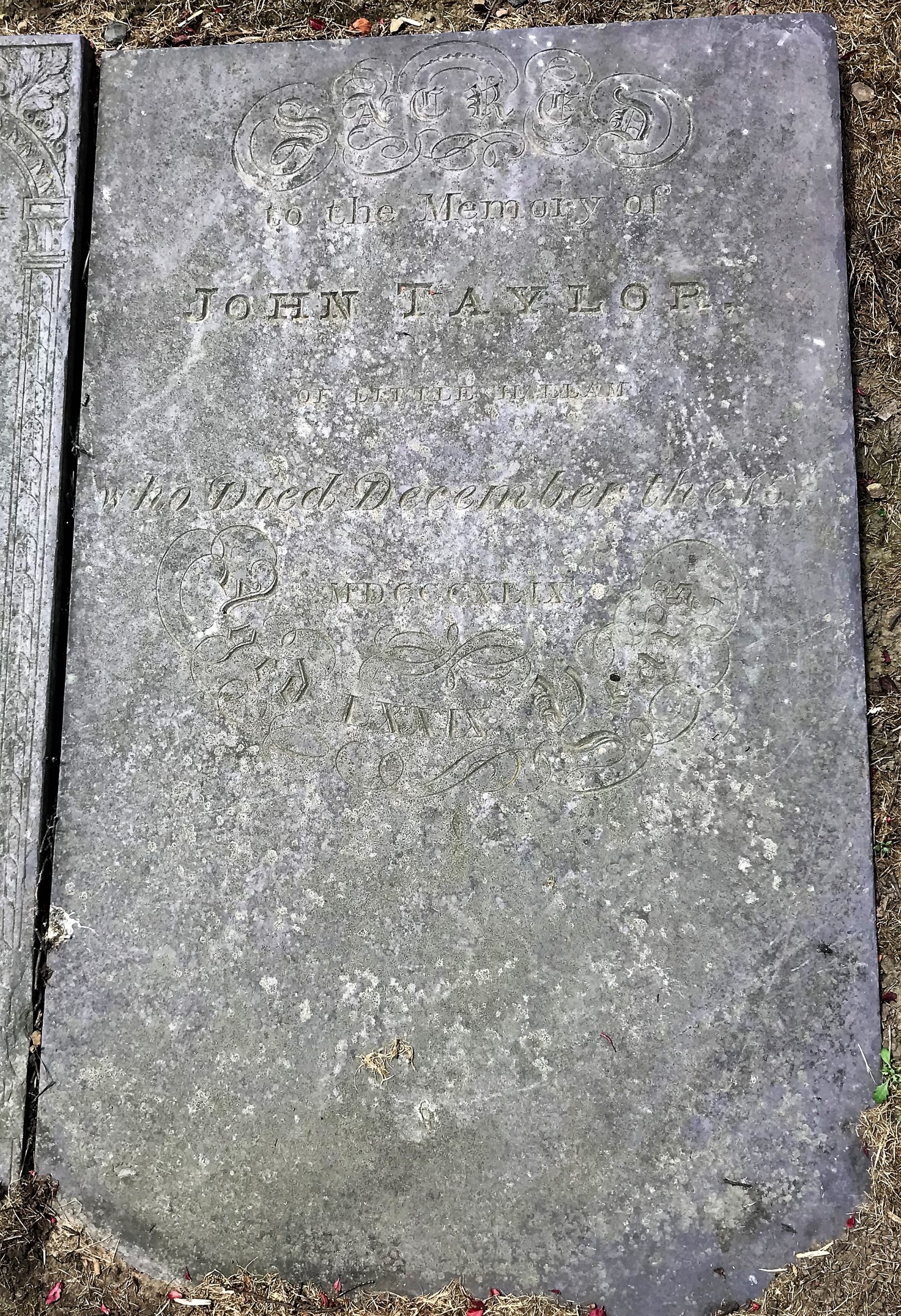

John Taylor the First was a farmer with land in Little Hallam, Ilkeston and Sawley. On May 22nd 1764 he married Sarah Swift. He died in 1793.

John Taylor the Second was their elder son, born in 1770. He married Hannah Cocker in 1794 and died in 1849

The only surviving son of John the Second was John Taylor the Third, born in 1811. He married Elizabeth Frearson in 1844 and died in 1892.

The only son of John the Third was John Cocker Taylor (1850-1867)

The gravestone of John Taylor, in the south side of St. Mary’s churchyard — can you work out which John it belongs to ?

This is what Adeline writes about the Taylor family (Can you spot her mistakes ?) …

The Manor House was occupied by Mr. John Taylor, a gentleman farmer, his wife, son and daughter. Young son, John Cocker Taylor and his sister, who was older, attended the British School when Mr. Holdroyd was the head. The lad caught a chill when out shooting. Rheumatic fever supervened, from which he did not recover. He was about sixteen years of age.

Miss Taylor and her mother used to drive each morning in their pony carriage to their farm in Kirk Hallam. Mrs. Taylor always wore a velvet bandeau across her forehead. She was the last of the Cocker family.

After Mr. Taylor’s death, Mrs. and Miss Taylor left Ilkeston and so ended the line of Cockers.

The mention of “young son John Cocker Taylor” means that the ‘gentleman farmer‘ who she is writing about must be John Taylor the Third; she suggests that John Cocker Taylor’s mother, (unnamed by Adeline), was a member of the Cocker family, and after her husband John the Third died, she left Ilkeston with her daughter, also unnamed.

However, born in 1850, John Cocker Taylor was the son of John and Elizabeth (nee Frearson), and he had one older sister, Mary, born in 1845.

John Cocker Taylor did died prematurely, of spinal meningitis, on June 17th, 1867, aged 16. Some years later both his parents and his sister all left Ilkeston to live in Spondon.

It was his paternal grandmother and not his mother who was a member of the Cocker family … she was Hannah Cocker (1773-1838), the daughter of John and Hannah (nee Deverall), who married the grandfather of John Cocker Taylor — that is, John Taylor the Second (1770-1849) — on November 18th, 1794.

At the death of his father in 1793, John Taylor the Second inherited the property, both copyhold and freehold, at Little Hallam. And just over a year later — on November 18th, 1794 — his marriage ‘amalgamated’ the Taylor and Cocker families.

John Taylor the Second died at his Little Hallam farm on December 5th, 1849, aged 79. However his wife Hannah (nee Cocker) had died at the same place before her husband, on November 18th 1838, aged 67. The couple had ten children between 1796 and 1819. The first one — a son named John, born in 1796 — died in infancy, in 1798. The only other son was John the Third, born in 1811.

There were eight daughters.

Mary was the oldest, born on January 25th 1798, and for over 50 years she remained with her parents. Only after the death of both parents did Mary marry — on December 21st 1854, at the Independent Chapel in Pimlico, to Daventry farmer Joseph Burbidge. Mary died on August 1st 1867 at their home of Badby Cottage in Daventry — she was 69.

Sarah was born on November 19th 1799. She married farmer Joseph Parkinson of Wilsthorpe, Sawley, on June 4th 1833 and thereafter lived at his farm. After Joseph’s death in 1855 she continued working the farm until her own death in 1863.

Eliza was born on December 23rd 1801, and on September 27th 1825, she married the prosperous farmer John Fletcher, of Head House in Mapperley. She died there in September 1864.

Hannah was born on November 27th 1803. She married Matthew Hobson junior, graocer and draper of the Market Place, and died in 1862.

Martha, born on November 23rd 1805, married farmer Thomas Grammer of Greasley Hall, Nottinghamshire, on April 3rd 1827. Their eldest daughter Jemima, born in 1829, was the second wife of Matthew Hobson junior after the death of her aunt Hannah. Martha died in 1872, at Kinnerton Hall, Hawarden, home of her son Henry.

Ann was born on October 19th 1807 but died in January 1825, aged 17.

Frances, born on July 6th 1809, married on June 5th 1832 to Linconshire-born Jonathan Toule, a farmer then occupying land at Watnall, Nottinghamshire. About 1850, the family moved to Langford, a few miles from Newark and remained farming there. Frances died there on April 8th 1889.

Jane was born on December 8th 1819, like all her siblings, at Little Hallam. She married canal agent James Wood and lived most of her married life at Trent Lock near Sawley and Long Eaton. She died on February 6th 1888 at Hay Street in Sawley, aged 68.

Born on November 6th, 1811, ‘gentleman farmer’ John Taylor the Third married Elizabeth Frearson of Sawley Grange, daughter of farmers William and Elizabeth on May 21st 1844 at Sawley Parish Church. Their only daughter was Mary, born in 1845. I believe that she died unmarried, at Ford Villa, Victoria Street, New Sawley, on November 21st 1908, aged 64.

At the end of 1877 John Taylor junior put much of his farming stock at Manor Farm up for sale and left Ilkeston to live in Spondon with his wife and daughter. He died there on October 19th 1892, aged 81, and his body was returned to Ilkeston to be buried, five days later, in the Stanton Road Cemetery.

———————————————————————————————————————————————-

Frederick Shaw (1833-1895)

The south eastern corner of the Manor House in the last year of its life … 1960

In June 1878 builder Frederick Shaw moved into the Manor house, leaving behind his living premises at 109 Bath Street, between the premises of china dealer Richard Riley and the Alms Houses. He had been born in Ilkeston on April 23rd, 1833, the son of framework knitter William and Mary (nee Mather) and married Marina Matilda Hawley, daughter of butcher John and Mary (nee Burgin-Richardson), on June 11th, 1855.

Frederick’s family business

By the late 1880s Frederick Shaw had been in business for 30 years, then occupying an office and building yard in Rutland Street with a two-storied building, offices, stores, workshops, saw, planing, moulding and mortar mills, timber sheds and yards. He also had farming interests at his Manor Farm, adjacent to the Manor House, at the bottom of Heanor Road.

Early in 1886 Frederick gave up the farming, selling all his cattle, horses, wagons, carts, mowers, reapers, ploughs, harrows, etc., etc.. The Manor farm of 200 acres of pasture and arable land, belonging to the Duke of Rutland, was to be divided into small allotments. The Duke already had over 1000 such garden allotments in the town. This was all part of the Duke’s ‘small allotment scheme’ to make small holdings available to cottagers and others in the town. By 1894 the Duke’s agent, Robert Nesfield, was boasting that the Ilkeston allotments were let at a most reasonable rate, of £3 12s per acre. In addition and at his own expense, the Duke had laid out access roads and built fences, and had paid the rates. You couldn’t get a better deal anywhere else in the county !! However some Ilkestonians were far from satisfied with the allocation of allotment land in the area. Under the Local Government Act of 1894 it appeared to some that rural areas were finding it much easier to purchase land for allotment purposes than urban districts. In the Spring of 1896, after a large public meeting, constituents in Ilkeston approached their M.P. Walter Foster for help. He gladly agreed to raise the issue in Parliament in an effort to rectify this ‘most irritating anomoly’.

Close to the Gas Works in Rutland Street, Frederick Shaw had work premises which included a large two-storey brick building, 13 yards by 7 yards, used as a joiners’ shop and sawing shed, piled high with sheets of wood and finished doors and window frames. A flight of exterior wooden steps led to the upper storey and there was a wooden lean-to by the side of the main building, housing a sawing machine. On the other side there was an engine room with a steam boiler inside, and across the wood yard stood another long wooden shed, stocked with dry timber. About a dozen carpenters, joiners and sawyers worked there, among shafting and sawing machinery. You can see the potential danger if a fire broke out at the works …. which one did, on the evening of December 27th 1888.

The fire alarm was sounded and Frederick’s son William, rushed from his nearby home at the Manor House, to be greeted by an imense crowd of onlookers and a ‘raging inferno‘ which had already consumed the lean-to and had taken a hold in the main building. Ilkeston fire brigade had already been called but didn’t arrive for another hour !! —- by which time the whole of the building had been gutted, its walls collapsed. By 7 o’clock in the evening the fire had almost run its course and was being dampened down.

The engine shed and offices survived relatively untouched, in part thanks to the members of the assembled crowd; they had helped in moving timber to a safe place, carrying buckets of water, and working the fire engine. No-one was injured but an estimated £500 – £700 worth of damage was done — though the premises were insured, so Guardian Fire Office would be paying the bill ?

And did the whole episode prompt the Nottingham Journal to remark that it hoped that Ilkeston Corporation would institute a Fire-Brigade worthy of the public-spirited dreams of the Queen of the Erewash Valley ? (Dec 29th)

Frederick Shaw’s father had been born in Chilwell, Nottinghamshire, in 1796 and Frederick died at Chilwell House in Wilmot Street on June 13th 1895. He had finished building the house himself just a couple of years before — and had got into trouble with the Town Clerk in the process !! Frederick moved into the house in early 1893 without obtaining a certificate of its fitness for occupation from the Council. He had originally submitted a plan of the house, which had been approved, but then built unauthorised additions (a washhouse and cart shed) onto the property. Frederick’s defence was that he had left it to his surveyor to submit notice of the alterations but this was done too late — a defence which didn’t get him out of a fine of 20s plus costs.

By the beginning of 1895 Frederick was trying to sell Chilwell House, a leasehold comprising a drawing room, dining room, house place, kitchen, six bedrooms, bathroom, outbuildings and stabling for three horses, cart-shed with hay-loft, washhouse, etc.. It remained unsold at auction and Frederick died there nearly six months later.

Frederick’s oldest surviving son was Frederick junior, born on June 27th 1859, and he, too, was a builder. On November 27th 1882 he married Adela Green of Sough Closes, Ilkeston, and almost exactly seven years later the couple were at the Divorce Division where Adela was petitioning for a dissolution of the marriage. The grounds were adultery and cruelty, both of which the court was satisfield had occurred. A decree nisi was granted; Adela left to live at Fenwick House in Park Avenue, with her spinster sister Sarah. She died at the residence of her nephew, the Rev. William Harold Green, on August 22nd 1926.

In January 1899 Frederick’s son William Edwin, also a builder, secured a lucrative contract of £40, 000 to build the extensions to Mickleover Asylum: this included the erection of male and female wards, an extension to the laundries, an head attendant’s house and ten cottages for the attendants. By April it was reported that William Edwin was making ‘satisfactory progress‘ and that the work should be complete in about two years’ time (minutes of the Asylum Committee, Derbyshire County Council)

On the 1891 Census the Manor House was occupied by commercial manager Moses Brewin Cotsworth and his family, but by 1898 it was occupied by George Porter Jackson, grocer and provision merchant of Bath Street. Then it boasted a dining room, drawing room, a breakfast room, two kitchens, six bedrooms, a bathroom and w.c., a store room, a large garden with a greenhouse, and a tennis court. It was owned by the Manners Colliery Company.

———————————————————————————————————————————————-

The Theatre Royal

Act 1: the Rutland Street Theatre Royal, 1893-1895

After the death of his father Frederick Shaw senior in 1895, William Edwin Shaw took charge of the family business in Rutland Street. And it was in that street, in September 1893, that Henry Vincent Clarke made an appearance. Only in his early twenties, he had been employed as a clerk by his father, Henry senior, who was a lace manufacturer in Nottingham. However in the late 1880s Henry Vincent decided that an acting carreer beckoned, after which his ambitious visions widened. In 1893 he was granted permission by the magistrates to build a theatre in Rutland Street, to be made of wood and to accommodate 1200 persons … on the “hire and purchase system“. William Edwin Shaw was contracted to supply the materials and to build the theatre. It was built ‘experimentally‘ and Henry had visions of a more ‘substantial’ structure, built of brick and stone which would be an ornament to the town if the present wooden theatre was a financial success.

But things did not go well !!

Less than a week before Christmas of 1893, William Edwin was at Ilkeston County Court where he faced Lucy Hardwick Woodhouse, “architect and surveyor” of West Bridgford in Nottingham. Lucy was the wife of Thomas Vernon Woodhouse and it was he who was the architect and surveyor, but being an undischarged bankrupt he couldn’t trade legitimately; so he was ‘represented’ by his wife — she was his ‘front’ while he was her ‘business manager’. William Edwin was suing Lucy for the timber he had supplied to her to build the theatre and she (via her husband in court) was counter-suing William Edwin for preparing the plans for him.

That the judge was not impressed by the case offered by the Woodhouses would be an understatement. He granted William Edwin the amount he had claimed as plaintiff, while dismissing the counter claim against him.

But all this was a side-issue for Henry Vincent Clarke whose theatre — The Theatre Royal — continued to trade. In August 1894 Lawrence Daly and company made a return visit to present “The Prime Minister” which was well-received … and a few days later was followed by “Our Boys”.

In October 1894 Henry Vincent Clarke had to apply for a renewal of his licence, including the right to sell drink … a formality in normal times except that he now faced opposition from the Licensed Victuallers’ Association which thought that the theatre was in opposition to their interests. The theatre had been operating in exemplary fashion, without rousing complaints or disturbance, and to the satisfaction of those in the neighbourhood. Audiences had numbered up to 1100 persons at a time. The victuallers of the town didn’t like the competition from the theatre’s bars but Henry pointed out that the bars were only available to patrons of the theatre. As a compromise Henry was asked if he would impose a charge in order for people to enter the bars, which Henry agreed to. His licence was thus renewed.

And flushed with this success perhaps, Henry now staged a ‘domestic drama’ … “Our Native Home” by Charles Whitlock and John Sargent, in which the ‘great sensation’ was the ‘famous dredger scene‘ where the heroine ‘predominently features’ and which ‘ought to satisfy lovers of the sensational’. How could you resist ?? And as a bonus, it included several good songs, one of which referred to local football.

Henry was now bounding from strength to strength !! His next production, a romantic comedy called “Man’s Ambition”, featured a water sensation on stage — two characters diving from a mill-window into the mill below, filled with genuine water !! Then, battling their way out and onto the stage, this time to soak up the applause of the audience.

Fred Graham was always a welcome face for Ilkeston audiences, and he and his troupe were back in February 1895, bringing with them the pantomime ‘Cinderella’. And then shortly after, in complete contrast, the theatre put on the melodrama, “Humanity”, starring John Lawton as the Jew and Frank Oswald as the villain. In the final scene the two came together in a fight on the mechanical staircase, during which some champagne bottles were accidentally shattered at the foot of the stair. The broken glass restricted the planned fight such that both actors had to ‘improvise’ … with the result that Frank caught his leg in the stair and broke it between the knee and ankle. He paid an impromptu visit to Ilkeston Hospital and was expected to be off the ‘boards’ for several weeks.

March 1895 … Mr. Henry Vincent Clarke has some good news and some bad news. Which do you want first ??

The Bad News ? — the present wooden structure in Rutland Street known as the Theatre Royal will be permanently closed after Whitsuntide (groans of disbelief !!). It was to be sold and pulled down.

The Good News ? — a handsome brick structure on a more central site will be built, and hopefully opened in September by the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company (loud cheers of approval !!). It will be situated in the newly-opened Lord Haddon Road.

The ‘final’ curtain came down in early June when the Company led by John D. Saunders (who also played the hero Stephen Merrick) performed “The Lightning’s Flash” by Arthur Shirley, to a crowded house … “final curtain”? … almost

The Theatre Royal had a further use, in July, when it hosted election meetings by both Sir Walter Foster (Radical Liberal) and Captain Baumgarten (Unionist Conservative), as the 1895 General Election campaign in Ilkeston drew to a close.

It appears that the June ‘final’ curtain was not final !! On August 5th the theatre was re-opened for a week’s run with H. Barr and R. Grahame’s Company production of “Life”, a ‘realistic drama full of fun and tragedy‘. … and then it closed ?? … not yet !!

This was followed later in the month by an amateur dramatic performance in aid of the funds of the Ilkeston Town Football Club.

And in the following month, a millitary drama, “At Duty’s Call“, complete with realistic battle scenes and the rescue of General Gordon … and there was more to come next week. Thus at the end of the month, Ilkestonians were able to go and see “Her Wedding Day”, a thrilling melodrama … ‘one to just suit the palate of an Ilkeston audience’.

Act 2: The scene is set and Lord Haddon Road is opened 1895

September 25th 1895 and the Duke of Rutland was back in town, a town which was gay with flags and festoons of bannerets and evergreens and flowers … and mottoes giving a kindly welcome to the distinguished visitors. This was not a municipal occasion and so was not recognised by the Town Council. The Duke was at Ilkeston to open a new private road, developed by W. Woodward and W.A. Blaine. That couple had already been responsible for other building developments within the town; in the last five years they had opened up the Stamford Street ‘estate’ and then the Wilmot Street ‘estate’. Now their latest venture, with two more entrepreneurs, (Edward Kirk of Nottingham and Arthur Chapman of London who had leased the land from the Duke) was this Lord Haddon ‘estate’.

The whole enterprise covered 36,000 yards, with the new road being 450 yards long and 50 feet wide. Many buildings along the road were being constructed already, including the new Theatre Royal and Opera House, expected to be complete in seven weeks’ time, and promising to be ‘an ornament to the town‘. It was planned to contain a pit, circle and boxes, accommodating 1600 customers, and was designed by architect William Dymock Pratt of Sneinton, Nottingham, the builder being William Savage also of Nottingham. The lessee was, of course, Henry Vincent Clarke of Ilkeston. William Pratt had also planned the new road which was constructed by Wain and Cope of Ripley.

It was a gloriously sunny day as people in their hundreds turned out for the occasion, Although not a municipal event, the Mayor Frederick Beardsley was present to greet the Duke as he arrived at the Midland Station at midday … and so too were councillors, vicars and other clergymen, the Town Clerk, J.Ps, magistrates, leading tradesmen and various solicitors. And little Miss Mary Binney who presented a bouquet of flowers to Lady Victoria Manners, the Duke’s daughter and his female companion for the day (his wife was ill).

As you would expect, those responsible for the development were in the procession which made its way from the station, with Derbyshire Yeomanry, Sherwood Foresters, various mounted police, volunteers, volunteer bands, the fire brigade and numerous carriages. They all made their way initially to the Heanor Road hospital (of which the Duke was the President), and then, via Charlotte Street, Cotmanhay Road, Granby Street and Bath Street, to the new road. The ceremony at the ‘entrance’ to the road was the unfastening of a silken cord, followed by the official naming of the thoroughfare and its opening to the public. Then on to Wilmot Street, Bath Street, the Market Place, along South Street to White Lion Square and a visit to the poultry show there (which the Duke also opened, at John Shaw’s Croft).

The final part of the journey took them all back to the Manor Recreation Ground where luncheon was served in a marquee.

By April 1897 sixty lime trees had been planted along the road, at the instigation of the Duke of Rutland, to commemorate the sixty years of the reign of Queen Victoria.

Act 3: Lights, camera, action !! and the new Theatre Royal opens 1895

On October 31st, 1895, Henry Vincent applied for a renewal of the licence for his Rutland Street wooden theatre for another year. Although it was known that a new brick theatre was being built in the new Lord Haddon Road and thus a transfer of licence would soon be applied for, this renewed licence was granted.

The contract for this new theatre was £2537 which Henry Vincent couldn’t afford !! He had no money !!! Egged on by his ‘agents’ he borrowed money and took out at least seven mortgages. Thus, on very shakey financial foundations, the New Theatre Royal and Opera House was born on Lord Haddon Road — and opened on December 23rd, 1895, “an imposing and commodious temple of Thespis ….. a brilliant electric light illuminated the front of the building enabling threatregoers to see the path along a track specially laid for the occasion. The interior of the theatre was brilliantly illuminated by means of the ‘sunlight’ in the ceiling, and the hot water heating apparatus diffused a sense of comfort through the place”.

Henry Vincent Clarke opened the proceedings by appearing in front of the audience to remind those present that at the closing of the old theatre he had promised that the new one would be opened on the Monday before Christmas, and he had kept his word.

The dress circle and second circle were well filled, though most of the audience was in the pit, the lowest-priced part. A heavy crimson curtain covered the stage until it was drawn up in folds as the action began.

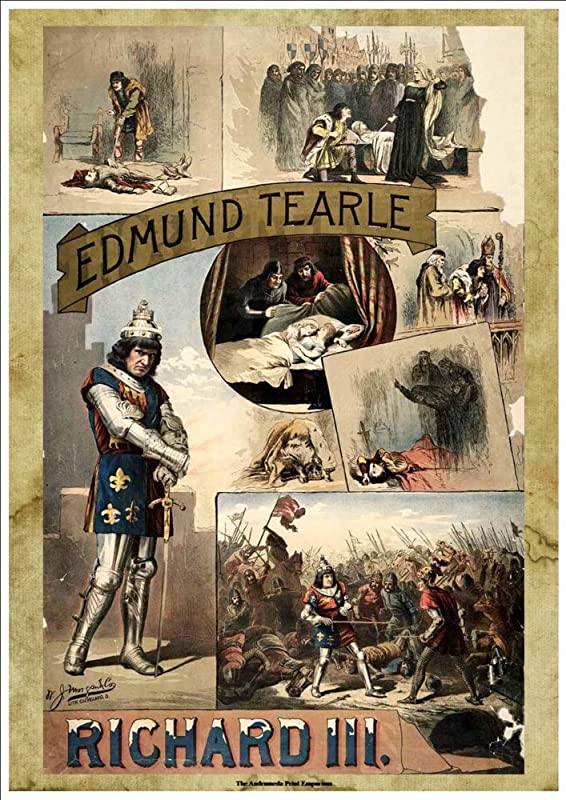

The chosen engagement was that of Edmund Tearle and his London Company, performing Sheridan Knowle’s tragedy “Virginius, the Roman Father”.

Further plays by the same company followed for the rest of the week — “Othello”, “King Richard III”, “Julius Caesar” and “Macbeth”.

“King Richard III” was performed before a crowded house on Boxing night, nearly 2000 persons being present.

A great many had to stand throughout the performance.

By this time improvements in the scenery had been introduced.

The play was received ‘with great favour’

And of course, by this time, the new road had been opened.

At the beginning of January 1896, Henry Vincent and his Theatre Royal were granted a full licence to stage plays and sell drink within the theatre. despite the opposition of the Licensed Victuallers’ Association.

It all sounds very grand doesn’t it ?? However behind the scenes, it wasn’t quite that grand. The theatre was already operating at a significant loss and Henry Vincent wasn’t a rich proprietor who could absorb this loss; he wasn’t rich at all and was often looking for ways to economise. One way of course was to build his new brick theatre without having the money to pay for it !! Another way was to delay or avoid paying any bills. In December of 1895 he had employed Rutland Street plumber Henry Moorley to remove gas pipes from his old theatre and put them into the new one, and had belatedly paid for that work. In January 1896 more plumbing work was done but this time Henry Vincent neglected to pay at all. Henry the plumber took Henry the theatre owner to court, sued him and won his £15 5s 3d.

Act 4: under new management July 1896 -February 1897

Henry Vincent Clarke was finding it increasingly difficult to pay his bills and soon joined the ranks of bankrupt businessmen with debts of £5377 and assets of £0. He left for 44 Muskham Street in Nottingham where he was now “a late theatre and opera house proprietor“; instead he was a clerk once more, this time for the Corporation Gas Department. And at the end of July 1896 the Theatre Royal welcomed a new manager. Born at Darlington in 1843, he was Frederick Edwin Harrison Neebe, a man with previous experience. This came, in part, from Exeter where he had managed the Old Theatre in Bedford Circus from 1869 to 1885 — a theatre which accommodated many celebrated actors like Edmund Kean, Charles Kean, Charles Matthews, Phelps and others. In 1877 Frederick also took the Bath Theatre.

The Old Theatre of Exeter, which burned down in 1886 (Exeter City Council)

From 1889 Frederick spent a couple of years in Australia, returned to England in 1891 and then experienced a few difficult years in the trade until the chance opening at Ilkeston presented itself. Frederick was able to show his testimonials from the Bath Theatre Company (with whom he had spent seven years) and Nottingham Theatre Royal, and in July 1896 he was granted a new dramatic licence for the Ilkeston theatre. Almost immediately he approached the magistrates for a temporary new drinks licence… only to be told he would have to wait until the former manager, Henry Clarke, surrendered the old one. This was duly done.

Just before the August Bank Holiday of 1896 several alterations to the theatre were completed. The pit stalls were removed while the front part of the pits had its seats backed and became a reserved area. The promenade was also fenced off from the pits. And then on that Bank Holiday Monday, August 5th, the theatre was re-opened with F.G.Kimberley’s Company in Miss Dillon’s romantic drama “A Fight for Life”.

In October 1896, the mid-month presentation was “It’s never too late to mend”, one night of which was set aside by Frederick as a benefit night on behalf of the Ilkeston Town F.C. The team had just won the Derbyshire Cup, which was paraded on stage at the interval by three of the players “in their football toggery”.

As the New Year opened Frederick seemed to be making a financial success of his theatre, with many of the best companies booked for the coming spring and autumn seasons. However in early February he contracted a cold which later was diagnosed as typhoid fever. Within a week Frederick was dead, at his Stamford Street home, on February 13th, 1897, aged 54: he had been the theatre’s manager for just seven months.

He was buried on February 16th at Park Cemetery. It took some time for “The Stage” magazine to catch up !! It was still advertising ‘the Royal’ as being managed by Frederick even after his funeral.

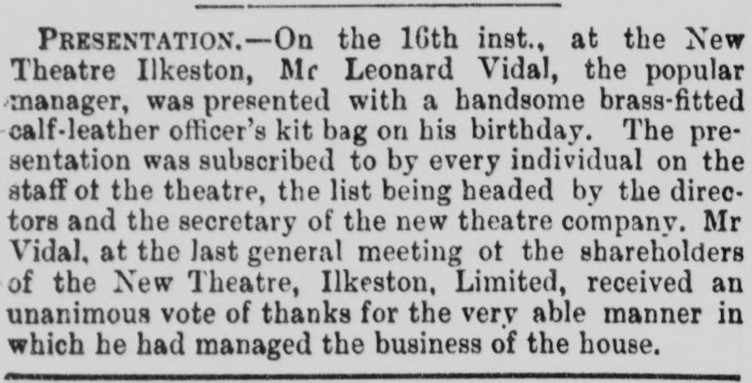

Frederick was followed as manager by Leonard Vidal, the latter coming from the Grand Theatre in Nottingham. On Boxing night of 1898 all previous records were broken when 2107 people paid at the door to see “The Days of Cromwell” by G. Howard Watson. Obviously Ilkeston folk were enjoying Leonard’s playlist.

Leonard introduced Ilkeston to “perhaps the most attractive show that has ever visited the Theatre Royal !!”

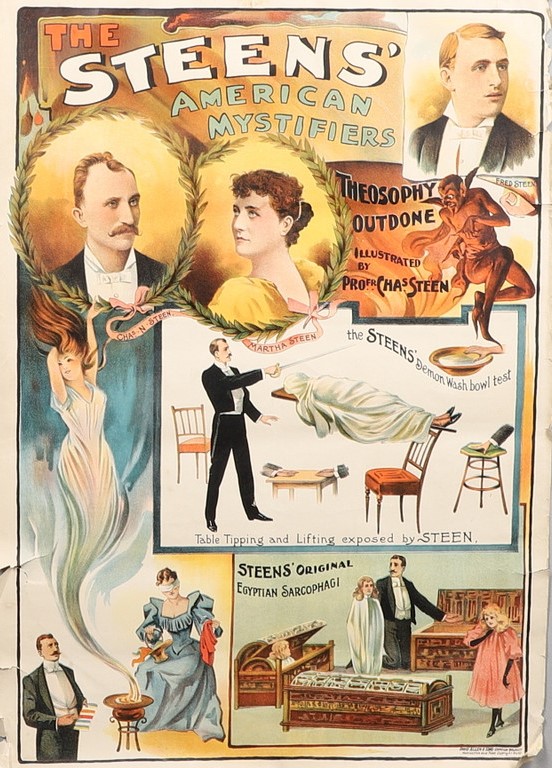

June 1897; The Steens, the American mystifiers

The weird occultism completely mystifies not only the onlookers but the specially privileged gentlemen, lawyers, schoolmasters, who have been on the stage with a view to testing Mrs. Steen’s marvellous powers of second sight.

One gentleman : “Damned clever !!”

Supporting acts:–

the excellent vocalism of Fred Wilkins and Mr. J.S. North;

the comedy of the ‘Black M.P.’ and the Shakesperian comedian Mr. Tom Bassett;

and last but not least, the Steenomatographe, with its life-like pictures.

August 1897: a short interval — while there is a change of scenery

It was during the summer recess that Leonard showed himself as a man of taste — I leave you to decide what sort of taste that would be. However he chose to redecorate the theatre throughout and employed George F. Skeens, painter and paper hanger of Hyson Green, Nottingham.

The Long Eaton Advertiser (August 14th, 1897) later gave its verdict.

George Wheatley was a 41-year-old ex-miner of Ash Street who had, just that week, taken a job as a check-taker for the pit area at the Theatre Royal. On September 14th, 1897 he was at the theatre as usual when he suddenly collapsed and died. An inquest into his death was held the following day at the Ancient Druids’ Inn but as George had been suffering from a ‘diseased eye‘ — the result of a blow received from a pick while working at the Oakwell Colliery some three months before — it was thought advisable that a post-mortem should be made. It was performed by Dr. Tobin. In fact George had lost the sight of his eye as the pick point had struck it.

The inquest’s conclusions: The right eye of George was cloudy, the result of an inflammatory attack, perhaps caused by a blow. The brain was perfectly normal; in fact it was a magnificent specimen of brain, the finest the doctor had seen for a long time. However the heart was in a flabby condition, with disease in the mitral valve, sufficient to account for death. And this was, indeed, the cause of George’s death.

The theatre production at the time was “Taken by force”.

It was around this time that the theatre came to be referred to as “The New Theatre” though the old name of “Theatre Royal” was still used at times !!

April 1899: just a few lines of poetry

At the beginning of April, the “Women in Black Company“, managed by Henry Rutland, was appearing at the New Theatre.

Henry put in an application to the magistrates at the Ilkeston Police Court, for permission for his seven-year-old daughter Winifred to take part in his production. All she had to do was recite a few lines of poetry. Permission granted.

Summer 1899: from strength to strength

And yet more affection for Leonard …

From the Era, November 24th, 1900

————————————————————————————————————————————–

An Edwardian view (about 1903) of the Theatre Royal/New Theatre in Lord Haddon Road (from a Pioneer Series postcard)

———————————————————————————————————————————————-

And now for a short interlude at Jackson Avenue, before we venture out into the wilds of Cotmanhay