A turning point: Forster’s Education Act 1870

Leaving behind the crisis at the British School …

In the early 1870s the leading position of the Anglican Establishment in providing Ilkeston’s education was now to be seriously challenged … especially by Forster’s Education Act of 1870 and the establishment of School Boards and non-denominational Board Schools in other parts of the country.

It was in 1870 that Education Acts began to be introduced to ensure the education of young children and to discourage their employment.

William Edward Forster’s Education Act of 1870 allowed existing Church schools to continue, if suitable, helped by a State grant.

However the country was divided into School Districts and in those areas where there was inadequate voluntary provision School Boards were to be elected.

A Board could raise rates and use the money to build a ‘Board School’ which had to be non-denominational.

Pupil attendance was not compulsory but was left to the Boards to enforce.

School age was from five to under 13, children still having to pay fees although the Board could exempt children if it thought fit.

A new Church (or National) School for Ilkeston

1873: Planning for new National Schools

The passing of Forster’s 1870 Education Act aggravated religious tensions within Ilkeston and led to more activity as each side of the religious divide tried to finesse the actions of its opponents.

The new vicar — since August of 1873 — John Francis Nash Eyre, and the Duke of Rutland again came together to resist the establishment of a School Board in Ilkeston and thus the threat of more non-denominational education in the town. The National Schools in the Market Place had served their purpose for a time but were now too small for the necessities of the parish. The town was short of school places – almost 800 children needed to be accommodated. So the erection of three new school rooms was proposed, on ground donated by the Duke of Rutland at the Cricket Ground, to the south of St. Mary’s Church.

Plans were also afoot to enlarge Shipley Schools and to erect two other new schools, at the northern end of the town (Holy Trinity) and at the southern extremity, in Hallam Fields.

And all this was to be financed by ‘voluntary subscription and effort’, thus avoiding the necessity of a School Board.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

1873: For and against a School Board

A public meeting was called by the Church Party in November 1873 to outline the plans and discuss the benefits or otherwise of a School Board for Ilkeston.

Just prior to this the Ilkeston Telegraph set out its view.

Liberal and Non-Conformist in aspect, it reported that the new vicar “intends to submit a plan, whereby the educational deficiencies of the town can be met without the adoption of a School Board. We think that a longer experience in the town would make him less sanguine of his project. The leading dissenters are already convinced that any such project is chimerical, and are not likely to feel under any obligation to attend the meeting”.

Many of these ‘leading dissenters’ were in agreement. To them Rev. Nash Eyre was being naïve and his plans were ambitious and overbearing; he knew that there was no chance of the new Church schools being well-attended but he was ‘bent on putting his foot on dissenters’.

However, many did attend the public meeting which was held in the Boys’ National school-room and chaired by the new vicar, who at the outset stated that he had past experience of School Boards and knew what to expect.

For him, Boards were expensive and engendered confusion. He did not like compulsion, and would not himself be compelled to send his three children to school. Compelling children to go to school would “engender a great deal of bad feeling”. He was willing to keep the church catechism out of the projected schools and to allow Dissenting ministers free access to them to give religious instruction.

Several of the non-conformists present spoke against the vicar’s view but when a motion, proposed by John Wombell and seconded by John Columbine, was put to the gathering – “that in the opinion of this meeting it is desirable that the deficiency in the educational requirements of the parish be met by voluntary efforts of all denominations” — there was a large majority in favour.

It was shortly after this that the subscribers and friends of the British School decided to re-open it after its temporary closure.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

1874: Plans for new National Schools go ahead

On June 21st 1874 preparation work, by builder William Warner, on the new National Schools began. The ground was staked out, the first sods were turned, and the children of each existing Market Place school were present as witnesses.

And in the following month the Rev. George Searl Ebsworth paid a visit to the town when he gave the annual sermon on behalf of these Schools – morning and evening – the offertories of which were to aid the New Schools Fund. The popularity of George within his former congregation was such that the collections at these services were twice the usual size.

And then came a bonus contribution to the New Schools Building Fund !!

In July 1874 four lads were caught scrumping in an orchard belonging to Isaac Attenborough, near the Church graveyard. Their parents appealed to Isaac to be lenient with them and the farmer agreed not to prosecute if each ‘donated’ 2s 6d to the Fund. The bargain was sealed.

A similar fate befell three young scumpers caught in Samuel Fretwell’s orchard shortly after.

The parents of several other local young miscreants found themselves contributing to the funds of the National Schools, even after they were built. For example, in 1879, at the kind intervention of Samuel Streets Potter of the Park, three lads, found damaging shrubs near his home, were not summoned but had to make a donation of 2s each to the Managers of the Schools.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

1874: New National Schools start to become a reality

A beautifully fine day of August 19th 1874 and parts of the town were lined with evergreens, its streets crossed by evergreen arches, flags flying from windows and a new one from St. Mary’s Church tower. School children lined the streets as gentlemen on horses, a procession of carriages and two brass bands — the South Notts. Yeomanry and the Ilkeston band — accompanied the Duke of Rutland from Trowell into the town.

This was only the Duke’s second visit to Ilkeston; the first had been in September 1866 when he came to lay the foundation stone for the new Town Hall. And now he was back to lay a second foundation stone.

After a short church service the party of dignitaries made its way to the back of the Cricket Ground where His Grace laid the foundation stone of the new St. Mary’s National Schools. For the occasion the silver trowel, bearing his Grace’s crest, was supplied by Joseph Haynes, silversmith of New Street.

Tickets for a ‘post-ceremony’ Grand Banquet in the spacious marquee on the site were 5s, but members of the public were also allowed a view of the ceremony … on payment of 6d towards the building fund.

And then the Duke began to ‘stick the knife in’.

In his following speech he rejoiced “to think that this will be the means to save you from a School Board….not only because it will save you from paying rates, but also voluntary schools are better managed, and taught better and purer religion than the board schools” — He had it on the authority of Dr. Fraser, the Bishop of Manchester, for stating that the religious teaching of the voluntary sector was superior to that of the board schools.

What he wanted to see in education was not merely reading chapters out of the Bible but religious discussion and explanation of the Bible, something which Church of England schools could best provide. Religion should be carried about in the everyday lives of people, whether rich or poor. If rich it would enable them to carry their prosperity all the better; if poor, it would enable them to bear the adversity with the greater resignation. (Hear, hear)

He felt that now more that ever the lower orders, as well as the higher, should be offered educational opportunities. The lower orders had increasing political power and influence, and would receive more in future. Thus it was important for them to receive a very good education to guide their judgments and “enable them to steer between the extreme on the one side of egotistic prejudice, and on the other side of democratic passions”.

After these outdoor activities an elaborate banquet was held at the Town Hall. Unfortunately, as it later transpired, its proceeds were insufficient to meet its expenses, and the Rev Eyre, one of its organisers, was later to apply to the Local Board for a reduction in the fee charged for the hall. ‘After considerable discussion’ a reduction was refused.

All of this was reported upon extensively in the Ilkeston Pioneer. Its rival, the Ilkeston Telegraph, covered the event in less than one column inch: —

“At the new schools – The foundation stone of the new National Schools was laid in the Ilkeston Cricket Ground, on Wednesday. There was a great display of middle-class flunkeyism”.

On the same page the paper devoted almost two whole columns to the Miners’ Demonstration Gala at Ilkeston on the preceding Tuesday, August 18th.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

1875: Building begins

Isaac Warner was engaged to design and build the new schools but he died in January 1875 before the task was complete. His son William inherited the business and the building task was finished by him.

On Sunday May 23rd 1875 the new Boys’ School on the Cricket Ground was occupied for the first time when both boy and girl scholars were addressed at a special service by the Vicar and others.

By October of that year all three schools were built.

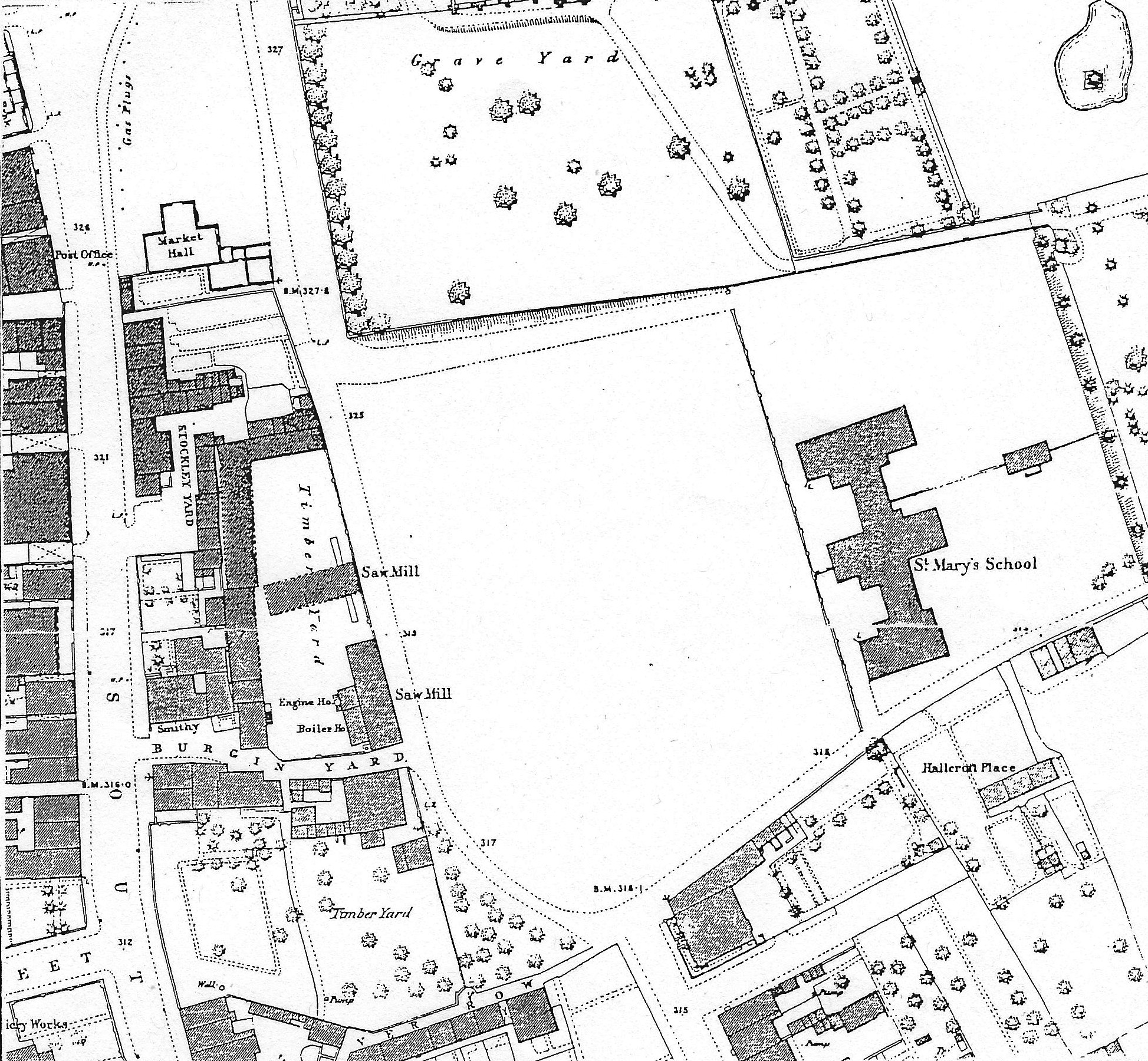

The new schools had three large rooms, parallel to each other, for boys, girls and infants, with classrooms between, capable of accommodating 600 children. You can see the three sections on the map below. Both boys and girls moved into the new buildings, leaving the Girls’ School in the Market Place to be turned into a ‘new’ Market Hall, marked on the map below ….it remained as such until about 1903 when it was demolished.

By the time of the October Statutes of 1875 the old Boys’ School in the Market Place had been pulled down, together with its boundary walls, leaving a much more open area for the fair.

On the left hand side of the map, you can see the old Post Office marked. The two premises directly north of it were demolished about 20 years after this map was drawn, to make way for the construction of Wharncliffe Road.

From South Street on the west, the top of the map in the north, the right hand edge in the east, and Weaver Row, just marked in the south …. the whole of this area was once known as ‘Hall Croft’.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

A new Cricket Ground needed

To make up for the loss of the Cricket Ground to the town as a result of building the new schools, the Duke of Rutland gave a large piece of land down Pimlico Lane to act as a replacement recreation ground. And which the Pioneer described as “three minutes walk from the old one”. You see it, below, as it was in 1928.

For a time the Rutland Cricket Club played at the Old Park, courtesy of its owner, Samuel Potter, before moving to Pimlico.

For Sheddie Kyme this was the beginning of the end of the gloriously successful years of Rutland Cricket Club.

The new ground was not fit for cricket, and this was more especially noticeable after a period of drought’.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

1876: a ‘new’ Market Hall in the Market Place

All this activity left the Market Place area with a more open aspect, but still not as today.

The Market Hall — the old National Girls’ School — now stood in the middle, and up to it, along the east side of South Street, stood housing. In the Spring of 1876 the following had appeared in the Ilkeston Pioneer …

Notice is hereby given that the building lately used as a Girls’ School, situated in the Market Place, Ilkeston, will on Thursday April 13th 1876 be opened as a Market Hall inthe place of the old building just taken down. By Order (of) John Fish, Market Superintendent and Collector.

Market Street stopped at Weaver Row and from there a path made its way past timber yards and saw-mills to the Market Hall.

This photo shows the crowd assembled in the Market Place, celebrating the Queen’s Jubilee in 1887. As we look at it, the Town Hall and the Sir John Warren Inn are behind our left shoulder, and we are looking diagonally across the Market Place towards where Market Street meets the Market Place (hidden in the top right corner).

The building seen on the top right (before which are the ‘dignitaries’ seated on a platform) is the old Girls’ Church School, built in 1851, and in 1887 serving as the Market Hall. (see No. 3 on the map) It is festooned with ragged political posters from the General Election of 1886, all advertising the ‘Committee Rooms of Mr. (Samuel) Leeke‘, the Conservative candidate who lost to his Liberal opponent, Thomas Watson. Many of the crowd on the left are standing on the site of the old Boys’ Church School, built in 1861 but demolished in 1875 (see No. 2 on the map).

Behind the Market Hall can be seen the top of the Church Institute roof, and next to it (left) part of Sudbury’s Factory in Market Street. Further to the left are two pairs of semi-detached houses and behind them you can just see the roof of the new National Schools built on the old cricket ground in 1875.

The wall you can see separates the Market Place from St. Mary’s churchyard.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

The Sandon Education Act of 1876 extended compulsion a little further but it was the Mundella Act of 1880 that stated that education was compulsory for all children aged five to 13, but that any child over the age of ten who had achieved a certain proficiency could leave or attend part-time.

—————————————————————————————————————————-

Before we move on (in time) let’s have a look at the building which William Warner constructed … the National Schoolrooms in later life