Girls first!! … in 1851

We are now in the mid-19th century and not to be outdone by the British School’s growth, the Anglicans now felt a need to expand their educational provision in the town. Plans for a new National School were drawn up by April 1850 (while John Ryder was the schoolmaster at the Butter Market School) and tenders to erect the building, together with a teacher’s residence, were sought. The architect had been chosen to be Robert Barber of Ivy Cottage in Eastwood, Nottinghamshire and Jedediah Wigley was then employed to build it.

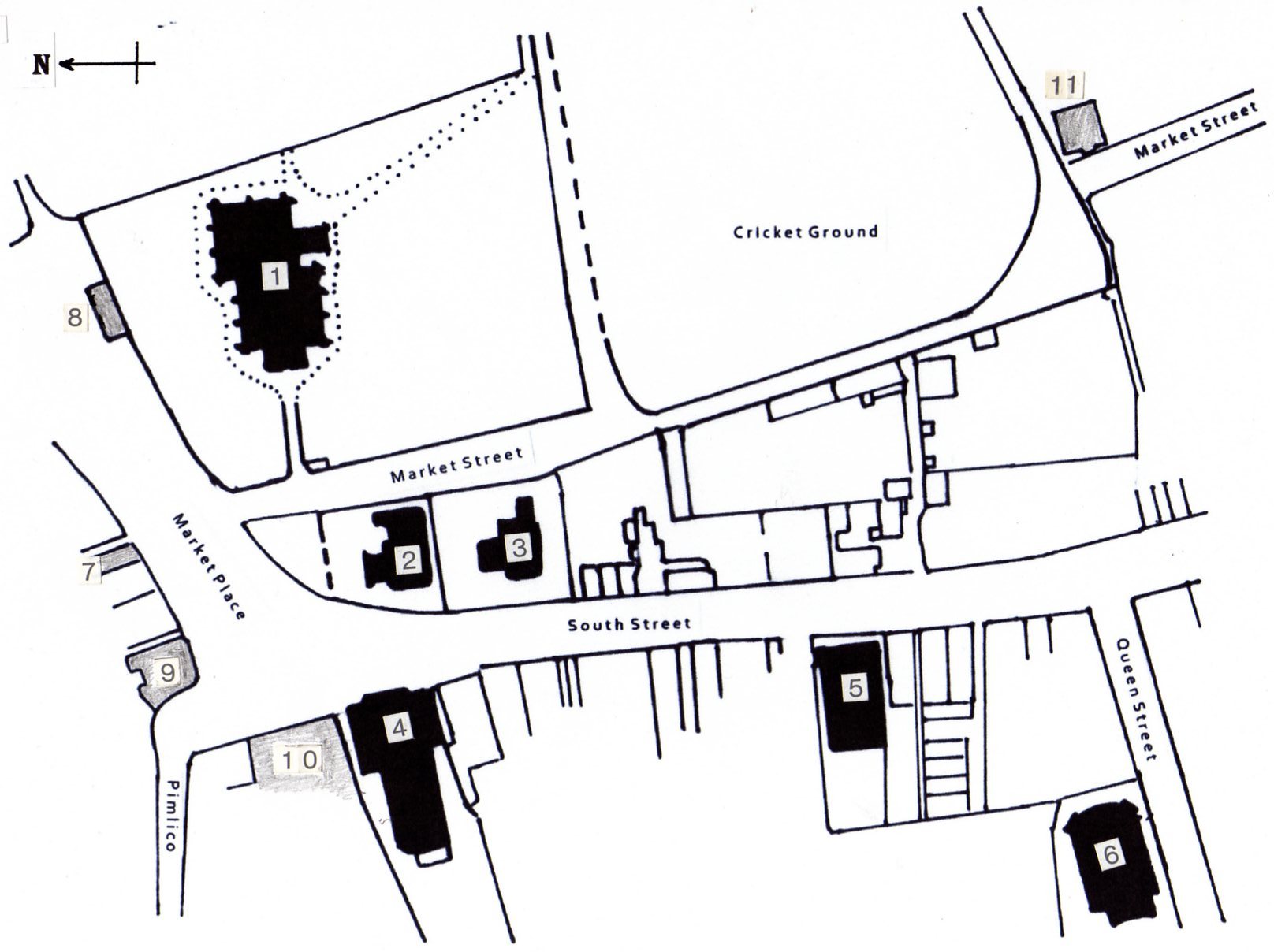

By January, 1851, the church community had built a new elementary Girls’ School on the south side of the present upper Market Place area, on land owned by the church. (Number 3 on the map below)

The old ‘Butter Market’ schoolroom (number 8) remained in use for their boys.

The Derby Mercury in 1851 (January 22nd) described the new School Room as having “a neat and pleasing exterior, is conveniently fitted up in the interior, and to all appearance is well ventilated” while to White’s Directory of 1857 it was “a handsome brick building, financed by subscriptions and grant, accommodating about 130 children, though average attendance is about 70”.

Entrance to the school was from the Market Street side.

Adeline writes that “Where the school was situated is now the site of the Free Library”. However her siting of this new Girls’ School is misleading.

Maps and photographs show it to be more in the middle of the Market Place, just north of the present Cenotaph, lying on a line between the Co-op corner of Wharncliffe Road and the Remembrance Cross in St. Mary‘s Churchyard. You can see a photo of it on the later page, The new National Schools on the Cricket Ground, (this was taken in 1887 when the Girls’ School built in 1851 was no longer a school but was serving as a Market Hall)

As one would expect in 1851, all teachers at the new school were members of the Church of England and its affairs were overseen by a group including the vicar, church wardens and a few other trustees. It could be argued that this close association between the schoolmistresses and the Church indirectly led to the death of Sarah Blake in April 1851.’

Sarah, aged 6, the daughter of Nottingham Road painter Richard and Sarah (nee Meakin), attended the new school and had gone there on a Wednesday morning, before the school opening time and while the mistresses were attending service at St. Mary’s Church. She was standing next to the open stove in the classroom when her pinafore was drawn into it, caught fire and badly burned the youngster. She died the next day. The subsequent inquest recommended that a fireguard should be placed around the stove and other fireplaces in the premises.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————-

But what about the boys??

But what to do with the boys who were still being taught in the miserable room above the Butter Market? Well – they just had to be patient!!

In 1860 another piece of land in the Market Place area given by the Duke of Rutland — a devout member of the Church of England — was ear-marked for a new Boys’ National School, opened on Tuesday April 16th, 1861. (Number 2)

This was a short distance to the north of the Girls’ School, on a line between the gates of St. Mary’s Church and present-day Wharncliffe Road.

To commemorate the opening, a church service was held during which the congregation was urged to support the present effort “to provide a truly religious and admirably useful education for the intelligent inhabitants of this increasing, thriving, and beautifully-situated town”.

One of first boys to move into the new school remembers that each pupil received “not only a bun, but a glass of wine! What a degenerate age we lived in, to be sure!”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————-

1870; A new schoolmaster’s house ?

Sheddie Kyme recalled that the new Market Place National schools – which were to become the Old National Schools when newer ones were built on the Cricket Ground in Market Street — had boundary walls on three sides, giving the area an enclosed and perhaps crowded atmosphere, not at all like the open, spacious appearance of today.

There were certainly some complaints about this ‘overcrowding’, especially when there was a rumoured proposal in 1870 to build a house for the schoolmaster, crammed between the two schools.

It appears that this plan was abandoned by the vicar because of the adverse public opinion.

But in the following year there were further rumours of an expansion of the Boys’ school into more of the open Market Place. But again this does not appear to have happened, at least not immediately.

The one side not bounded by a wall was the south side which bordered the properties of Isaac Warner and Robert Burgin-Richardson.

The front (north) wall of the Boys’ School had an iron rail along its length, supported by posts, running a little away from it, thus forming a walkway in front of the school and separating it from the Market Place. This walkway was approximately on a line between the entrance to St. Mary’s Church and the Town Hall frontage.

“There were very few boys in Ilkeston at that period who had not turned a somersault or otherwise executed some acrobatic manoeuvre on that most convenient horizontal bar “. (Sheddie Kyme)

He also recalls that these Anglican schools ‘had a very church-like appearance, the stone facings of the doors and windows, together with the diamond-shaped panes, leaving no doubt in the minds of anyone as to their origin.’

1873; Boys’ School extension

In the summer of 1873 William Warner was employed to extend the classroom in the Boys’ National School and had erected scaffolding around the structure to aid his task. As he was walking through the Market Place while the work was going on he caught sight of seven-year old Arthur Summerfield where he shouldn’t be – up the scaffolding!!

Not only that, but the lad had taken it upon himself to throw down any bricks that he could lay his hands on. Consequently by the time that William got to him, about a hundred broken bricks lay on the ground. The builder was rather put out, took Arthur off the scaffold, and ‘scuffed’ him several times with his open hand, though ‘not severely’.

But too severely for Arthur’s father, tailor William of Nottingham Road, who threatened to take out a summons against Bill the Builder.

To the exasperation of the Magistrates the whole matter ended at Ilkeston Police Court where the lad was ordered to pay 1s damages, a 6d fine, and 7s in costs.

This classroom extension was the last straw for at least one Ilkestonian.

‘Inspector’ wrote his letter to the Pioneer in June 1873 and he was outraged.

He had watched as first the Girls’ school, and then the Boys’ school, and now this extension, had all gradually masked the public’s view of the noble St. Mary’s Church. Much better, he thought, to knock down the existing schools and build them elsewhere, leaving the Market Place free for market purposes. His suggestion was to transfer the school to Pimlico or build in on the Cricket Ground next to, but not obscuring, the church.

He did not know it then but ‘Inspector’ would not have long to wait before his wish was partially granted.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————-

and from the Ilkeston Pioneer, October 30th 1873, a little ‘adult education’

——————————————————————————————————————————————————-

In December 1873 the Government’s annual report on Ilkeston’s National school was published.

Its financial position was sound and improving, and the progress of the scholars was satisfactory and steady, testament to the efforts of its master William Frost.

Miss Eleanor Bocock of Nottingham, the mistress of the Girls’ National school, had died in September of that year, aged 25, and there was a short hiatus before Miss Emma Elizabeth Widdowson was appointed — this interregnum had the effect of reducing the school’s grant.

The report stated that ….

“The work of the boys’ school is in every respect most creditable.

All the standard exercises were remarkably well done, and the literature was satisfactory.

Some good grammar was done, but it was not sufficiently advanced in the 5th standard.

The singing and general order were very pleasing, and the pupil teacher’s work most creditable”.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Poor parents — and perhaps others! — might be deterred from sending their children to these schools however, by fees, even if only a penny a week. Also for parents to consider was the wage that the child would not earn while sitting inside a schoolroom. To many it was far more important that their children were earning a few pence at the coal mine or in the lace-mill than sitting in a room learning to read a book they could never afford to buy.

And the attitude of many Government officials did not encourage them, officials who believed that children could be taught everything that was necessary, soundly and thoroughly, by the age of 10 or 11. What was the point of teaching them up to the age of 14 or 15? This was not needed and would be far too expensive.

An old Ilkeston resident recalls that in 1860 the coal-masters of Derbyshire and adjacent counties “in order to encourage miners to keep their children at school, offered substantial money prizes, to be awarded after an examination, to boys and girls of ten years and over”.

The prize-winners in 1860 were William Flint, aged 10, son of Frederick, tailor of Market Place, and Elizabeth (nee Knighton); William Shaw, aged 11, of William, coalminer of Duke Street, and Hannah (nee Straw?); Martha Fisher, aged 10, of William, grocer of Awsworth Road, and Penelope (nee Knighton); Ellen Straw, aged 11, of Thomas, coalminer of Heanor Road, and Ann (nee Jackson).

——————————————————————————————————————————————————-

After the 1858 Royal Commission on Elementary Education (the Newcastle Commission) ‘to inquire into the present state of education in England’ — it reported in 1861 — government attitudes developed along stricter lines.

In 1862, through a Revised Code, grants to schools were made dependent on attendance and on examination passes in reading, writing and arithmetic in six stages from age six to 11. Value for money !! (Where have we heard that before?) Until then the grants had been based simply on the amounts raised by local voluntary efforts.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Meanwhile, back at the Bath Street British School we have a crisis to deal with.