Adeline walks on down Bath Street and tells us that we “now we pass a low bank with a garden or two” and then we arrive at this Potter property which was “the Poplar, an old countrified-looking house with poplar trees in front of it.”

———————————————————————————————————————————————————–

The Poplar Inn …1795-1858

Enclosing the Common 1794-1798

Here is a little bit of historical background to this area. To help you visualise places I have used some modern place names which you might be familiar with but which were not in use until much later.

Up to the end of the eighteenth century, the area of Ilkeston from approximately Church Street in the north to just past Stamford Street, off Bath Street, in the south, was known as ‘The Common‘. Its western limit followed the path of Heanor Road/Bath Street while its east boundary was the River Erewash. You can find a map of the Common area here. (This description is very approximate, just to give an idea of the Common’s limits)

The Common was a vast stretch of open land where people who had ‘Common rights’ could graze their animals, according to how much freehold and copyhold land they had. ‘Common rights’ could be bought and sold. This system helped poor cottagers who wanted to keep a few pigs or cows, but of course favoured the rich.

From 1794 a process called ‘Enclosure’ began, when the ‘Common’ was divided up into parcels or strips of land, and allocated to private individuals, those with more ‘Common rights’ getting the bigger share of the enclosed land. Enclosures took a few years to complete.

From 1794 until 1798 William Gauntley compiled his Enclosure map for the Government Enclosure Commissioners which showed these new parcels of land. Each one has a number or letter so that the owner could be identified.

At the same time William Gauntley made a similar, more detailed map for the Duke of Rutland — a so-called Ducal survey entitled ‘a map at Lady Day 1795‘ — which showed a very similar pattern of land ownership to the Enclosure map.

The main difference between the two maps of William Gauntley was that they used different numbering systems !!

There were two further surveys of copyhold lands in Ilkeston in 1817 and 1848.

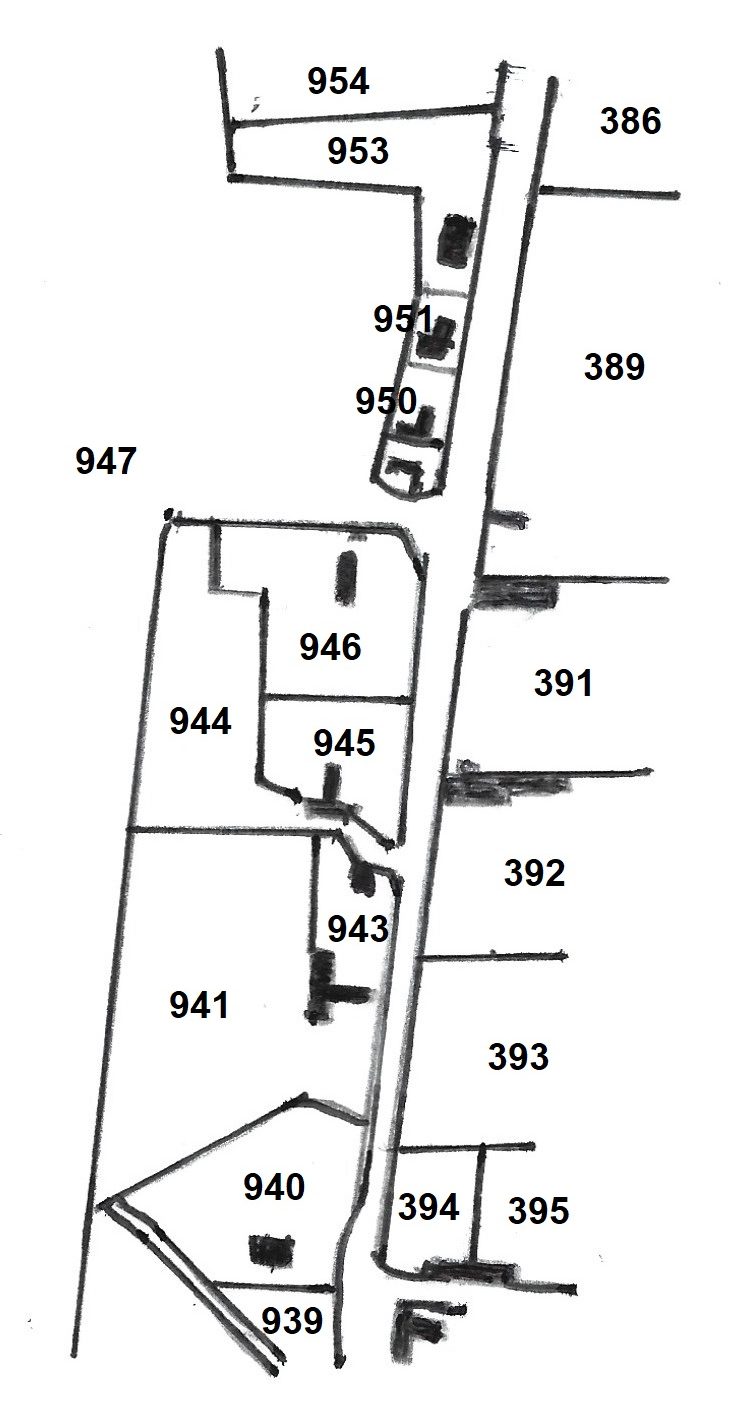

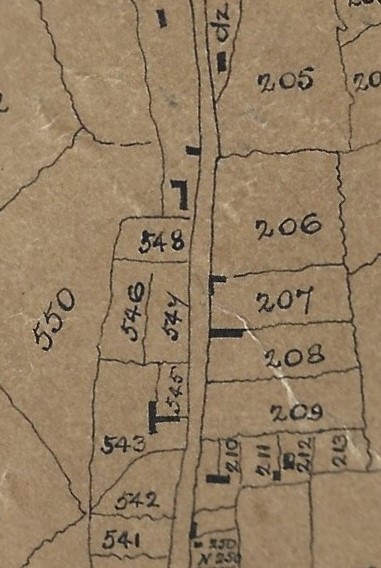

Both maps below show the same part of Town Street (later called Bath Street) … from approximately what was to be Stamford Street in the north, to Chapel Street site in the south. Town Street in unnamed, running through the middle of each map.

From Samuel Smith to James Potter senior …

The site of the Poplar Inn is in parcel 946/548, then owned by James Potter, miller and farmer, and was described as a ‘house and garden’ … no mention of an inn or beer house.

It had come to James from the family of tailor Samuel Smith who had died in 1759, leaving his property to his children.

You will notice how sparse are the buildings in this part of Town Street.

… and then on to James Potter junior 1806 …

When James Potter died in May 1806 his eldest son James junior took this portion of his estate, which was then described as containing ‘two cottages with gardens’. These were occupied by John Brentnall and Thomas Richardson. James junior died on September 22nd, 1822.

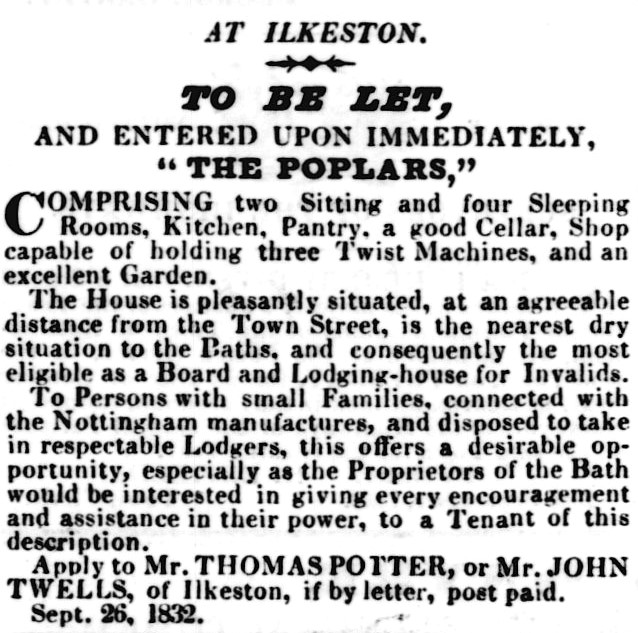

Ten years later, in the Nottingham Review and General Advertiser (March 2nd, 1832) “the Poplars Tavern” was advertised for let, 200 yards from the Baths where more information was wailting. And then, a few months later …

Nottingham Review and General Advertiser (September 28th, 1832)

… and then via William Hill to Thomas Potter senior 1844 …

By 1841 the property had passed into the hands of William Hill, the sole executor of the will of James junior, and at this time the two cottages were occupied by agricultural labourer, George Riley (aged 64) and currier John Glossop (aged 33) … they can be found in these Bath Street premises on the 1841 census.

In 1844 the property passed to Thomas Potter senior, the brother of James junior. Thomas was a coalmaster, liquor merchant and farmer living in Cotmanhay, and the premises were now occupied by his son, Thomas junior, a brewer. At this point the two cottages were combined into one.

…. and then on to (a different) James Potter who sold it to Francis Ebbern 1851 …

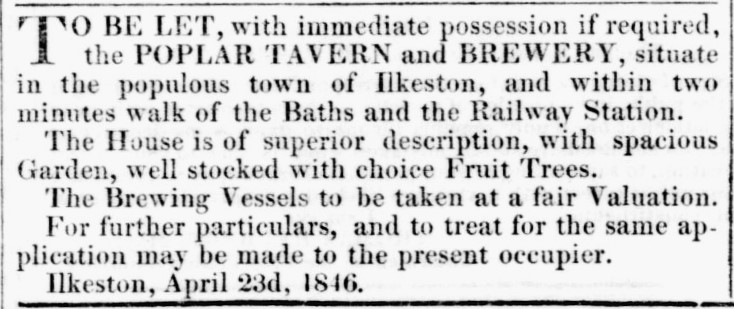

Thomas Potter junior died on June 8th, 1845 and a short time later, once more the tavern was offered ‘to let’.

from the Nottingham Review (April 24th, 1846)

Thomas Potter senior died on September 13th 1849 and in his will, dated April 18th 1849, the premises were described as ” a messuage or tenement, heretofore in two cottages but now occupied as three, with the garden thereto, sometime since in the occupation of John Brentnall and Thomas Richardson, afterwards of John Glossop and George Riley, since of Thomas Potter the Younger and now or of late of Matthew Elliott*, George Riley** and John Noon, being bounded east by the Town Street, west by land now or late belonging to the said John Bark, north by the land of the Duke of Rutland and south by lands now or late belongingto the said John Bark and to William Smith and Samuel Smith”.

*Matthew Elliott appears on Slater’s Trade Directory of 1850 as a beer retailer in Bath Street, Ilkeston … presumably at the site of the Poplar, although it is not named.

** George Riley is the same occupant as that mentioned in 1841. And both can also be found on the 1851 Ilkeston census, Matthew still as a ‘beer house keeper‘ and George as his neighbour.

In the 1849 copyhold survey (mentioned at the top), parcel 548/946 was described as containing a beerhouse, a dwelling and lean-to, a stable, brewery and a garden … while in September 1850 the inn was described as “having a frontage to Bath-street, of 43 yards, or thereabouts, and there is a well with a constant supply of excellent water, from which circumstance the property is well adapted for a Brewery”.

After the death of Thomas Potter senior, the property was passed down to James Potter, now the oldest surviving son of Thomas Potter senior. He had the property in October 1851 when he sold it to Francis Ebbern, a West Hallam farmer.

In a simplified nutshell therefore, the property came from the Smiths to the Potters and then, via William Hill, to the Potters once more, until it was sold to Francis Ebbern in 1851.

The beerhouse was subsequently occupied by Thomas Brown who makes an appearance in the Post Office Directory of 1855 as a ‘beer retailer, Bath Street’.

Thomas Brown was still there in June 1856 when the copyhold of the Inn was put up for sale following the death of the owner Francis Ebbern of West Hallam in April of that same year. In his will Francis left a life interest in the property to his widow Marina, and after her death, it was to be divided equally among his children (There were six living children at the time of his death).

Again, in 1858, the Ilkeston News advertised for sale this “dwelling house occupied as a beerhouse and called the Poplar Tavern, in the occupation of Thomas Brown”. This source is the earliest I have discovered to use that name of the Inn explicitly, although, as you can see from the description of its previous owners, it could be linked to the spirit/brewery trade as early as 1844 ?

———————————————————————————————————————————————————–

The Ebbern Family at the Poplar Inn 1851-1865

Adeline tells us that “Mrs. Ebbern, the landlady had two sons, and two daughters.” Once more she is undercounting.

A daughter of framework knitter and one-time victualler at the Boatswain tavern, William Burgin-Richardson and Elizabeth (nee Attenborough), Marina Burgin-Richardson had married West Hallam farmer Francis Ebbern in September 1835, and then had lived in that village until the death of her husband in 1856.

Francis had bought the land and premises in this area of Bath Street in 1851 from James Potter, coal agent and farmer.

This stands in West Hallam Parish Church grave yard. If you cannot read it … “In Affectionate Remembrance of Francis Ebbern who departed this life, April 4th 1856, aged 41 years”.

Born in 1840 their eldest daughter Elizabeth married Abraham Flint of West Hallam, coalminer son of William and Mary (nee Hobson) in January 1859.

The Harrison & Harrod & Co. Directory of 1860 shows Abraham as a beer retailer in Bath Street — most probably at the Poplar Inn — while mother-in-law Marina is listed as a farmer at West Hallam.

But by 1861 Marina had left West Hallam and occupied the Bath Street beerhouse, with three sons and two daughters, while Elizabeth and Abraham Flint were back in West Hallam with their daughter Mary and Abraham’s parents.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Later landlords 1865-1878

Marina was still at the Poplar in 1865 but by 1869 the landlord was Joseph Rollinson.

The Inn was at 52 Bath Street in 1871. The census of that year shows innkeeper William Green there (as Marina‘s manager?) but in July of that year the licence passed to William Ratcliffe who had left his Codnor beerhouse.

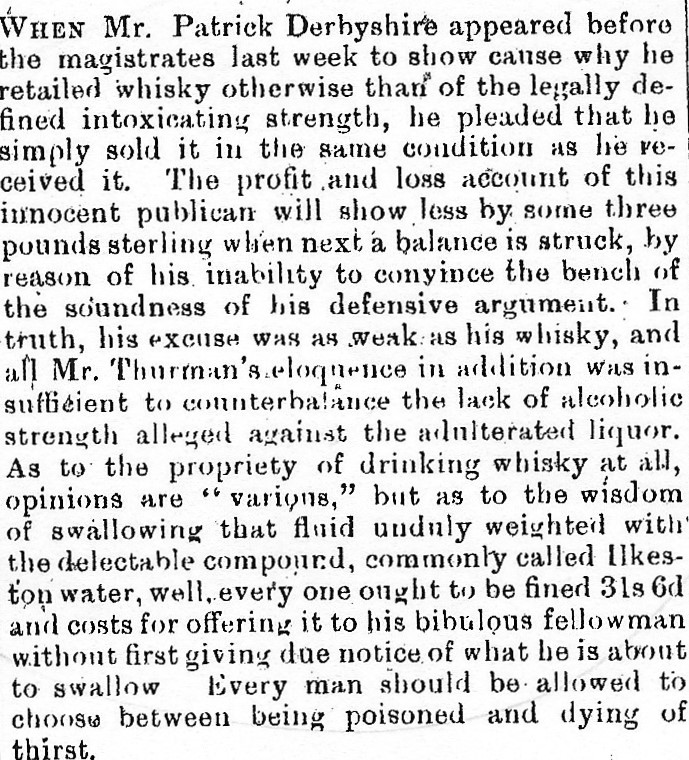

In May of the following year the license passed to Patrick Derbyshire while William Ratcliffe went to the Glass House public house in Codnor — which Griffin Wagstaff had just left to come to Ilkeston’s Spring Cottage Inn, just vacated by George Wright.

(Are you following this? )

Ilkeston Pioneer July 19th 1877

Patrick was at the Poplar until April 1878, although he ceased his brewery business there in February 1877 when he sold off his equipment.

Marina died in December 1878, aged 61, at the Bath Street home of her married daughter Frances Amelia.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

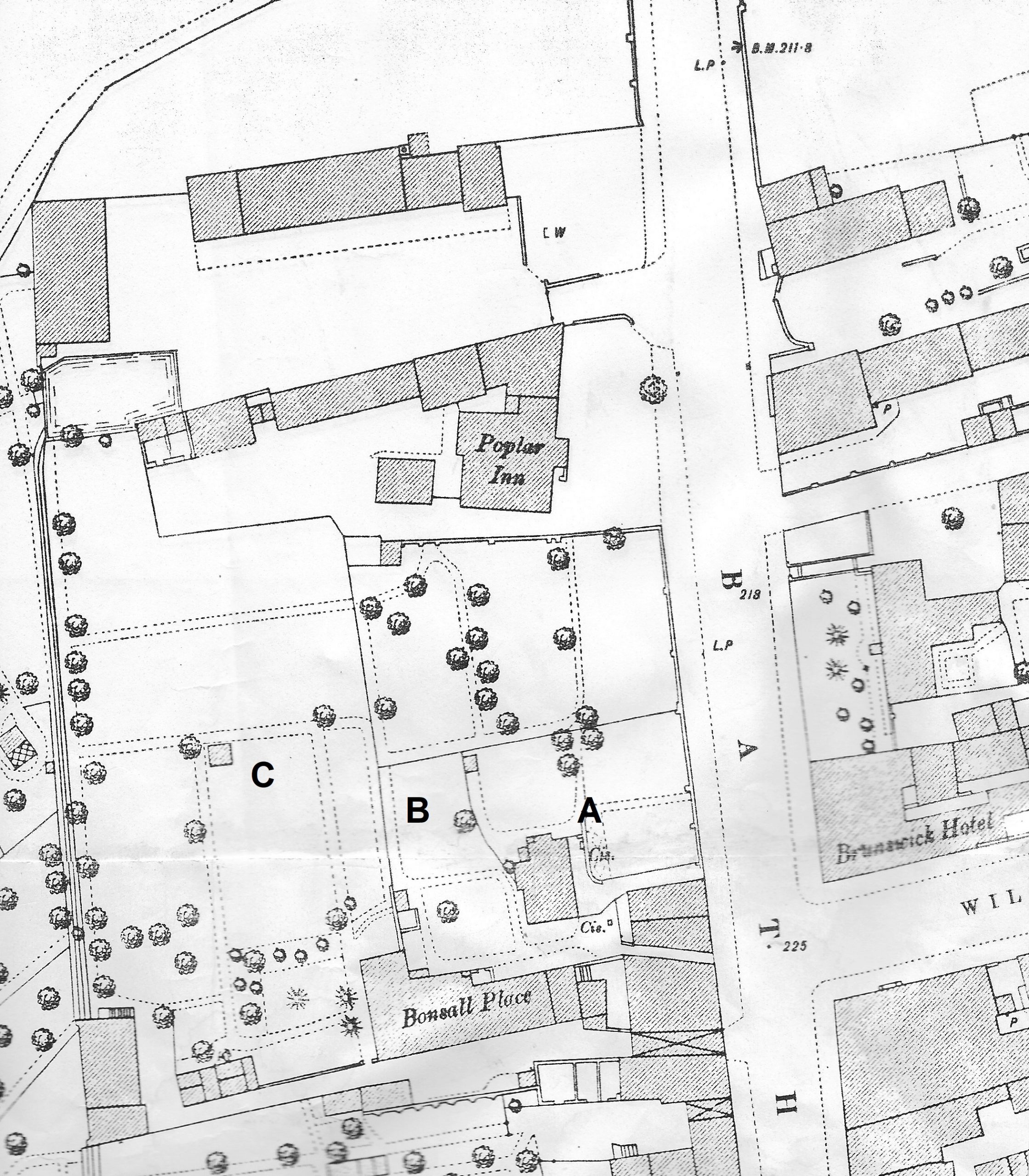

And here is the site of the Inn about 1881.

Notice that a single tree — a poplar ? — is shown at its frontage with Bath Street.

At A was the property of the late William Smith (1807-1874) which passed to his widow, his second wife, Catherine (nee Lings), whose elder sister Sarah had been married to tallow chandler Moses Mason, just across the street.

At B were the premises of Samuel Smith.

The property at C was part of the Bonsall estate.

The Duke of Rutland owned the land north of the Poplar Inn.

“The tavern deserved its name, for in front of it was a row of noble poplars, of which only one remains, a miserable relic of former stateliness”. (a letter from Bath Street in the Ilkeston Pioneer 1892).

———————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Ruth Gawthorpe has commented …

Marinah Ebbern nee Burgin Richardson … married Francis Ebbern in 1835.

He was a Coal Merchant from Coventry, whose family delivered coal by barge to the textiles industries all over the country. I think he must have stopped off one evening, gone to the pub and bumped into Marinah and fallen in lover – because her family ran the Boatswain according to your records.

Where was the Boatswain pub? I would love to be able to place it.*

Sadly Francis died in April 1856 and I think that his daughter Annie Rebekah was born on 6th July, 1856 – so they didn’t get to meet. That must have been a torrid time for Marinah.

Francis Ebberns name lived on in our family though. I have a photo of Annie Rebecca somewhere and will try to find it for you.

My Dad, Francis Ebbern Robinson, was her grandson and said she was formidable!

Francis is buried in West Hallam church (above) and his daughter, Elizabeth is next to him. West Hallam is where he farmed once he had sold his share in the canal transport business to his brother Tom. (I am not sure which farm.) I guess that it was this money that funded Francis buying property in Ilkeston (including the Poplar Inn), some of the property remained in the family until the 1960′s when my Grandad, Samuel Sydney died and my father and uncle sold it as it was in poor repair!

* The Boatswain appears in early nineteenth century trade directories occupied by William Burgin (1829) who died in 1830, then by his widow Elizabeth Burgin (-Richardson) in 1835, and then by their son James in 1841. I believe that around this time its name was changed to the Jolly Boatman (see Bagshaw’s Directory of 1846).

The address of the Inn appears in various sources as ‘The Potteries’ or ‘Canal Side’. It is shown on the 1881 Ordnance Survey map of Ilkeston on the west side of the Erewash Canal, a short distance to the south of Barker’s Bridge, where Awsworth Road crosses the canal.

If you look on Google Maps it was approximately at the east end of what is now Boatsman Close.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————

The Ebbern children…

After her marriage on January 18th 1859 daughter Elizabeth continued to live at West Hallam with husband Abraham Flint and their children. She died there in 1882, aged 42. Abraham died there two years later.

At West Hallam Parish Church, close to the stone of Francis Ebbern (above) we find the Flint stone (!!!)

“In Memory of Abraham Flint, died Sep 10, 1884, aged 52 years … and of Elizabeth Flint, who died Nov 25, 1882, aged 42 years”.

Born in 1842, eldest surviving son and coalminer John Ebbern married Hannah Morris Carrington, daughter of Heanor Road coalminer John and Hannah (nee Morris) on September 7th 1862 and six children followed before Hannah died in August 1876, aged 33.

Some time later — possibly about 1880 — John formed a relationship with Ann Powell (nee Wortley).

She was the wife of labourer Matthew Powell whom she had married in October 1872, by whom she had had at least two children –Sarah Ann (1874) and Elizabeth (about 1877) — and from whom she was soon thereafter separated.

Ann Powell alias Wortley then had a succession of illegitimate children who had a variety of surnames including Thomas Gideon Wortley (1880), Herbert Wortley (1882), William Ebbern Powell (1884), Thomas William Ebbern Powell (1885), Mary Ebbern Powell (1887), George Ebbern (1888) and William Ebbern (1890) though all but one died in infancy.

When Ann’s third illegitimate child — an unnamed daughter — died in January 1883 after two weeks of life, without a doctor being called, the authorities became suspicious of these infant deaths and an inquest was held.

Ann was then living with her parents at Lower Granby Street and her mother, Sarah Ann Wortley, had helped deliver the child.

From birth the baby was sickly — according to her grandmother — had suffered from convulsions, had refused food, and was ‘half gone’. She had given it castor oil but had not called a doctor. What was the point? In her ‘expert medical opinion’ the child was beyond help, expecting every moment to be its last.

The evidence pointed to convulsions as a cause of death, reflected in the jury’s verdict.

The 1891 census now showed John and Ann living together as husband and wife, at 7 Lower Granby Street with their daughter Mary and Ann’s parents, horse driver Thomas and Sarah Ann (nee Wrath).

However it wasn’t until 1901 that John and Ann were officially married.

John died at his home of 22 Springfield Gardens in December 1905, aged 63, and Ann also died there in March 1912, aged 59.

On Wednesday morning, June 7th, 1899 Ann discovered her father Thomas at their home (7 Lower Granby Street) in the process of attempting to commit suicide. He had cut his throat, though fortunately not too deeply; Ann intervened to stop him and then quickly got him to Ilkeston Hospital, by cab, to be attended by Dr. Harry Potter.

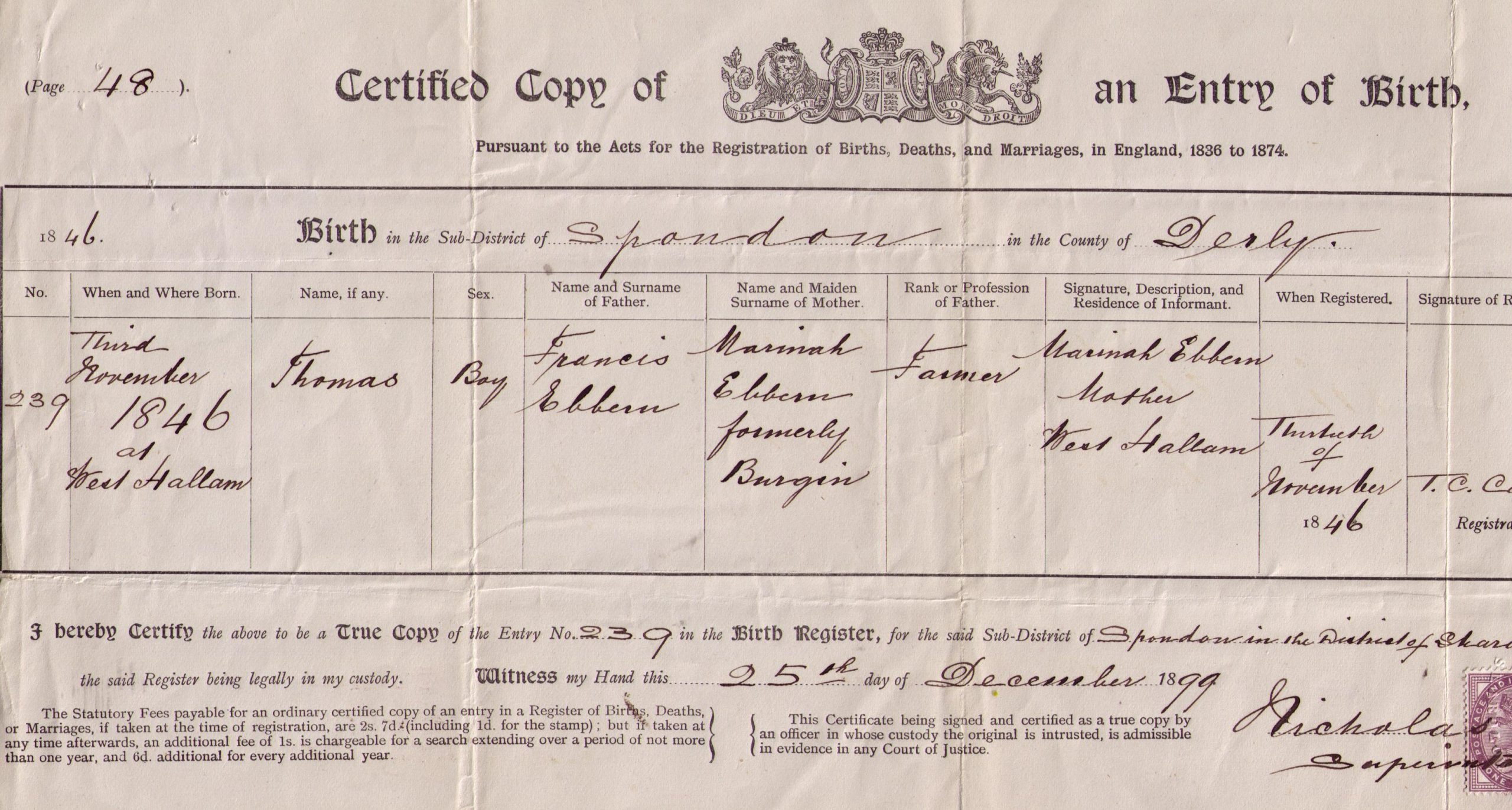

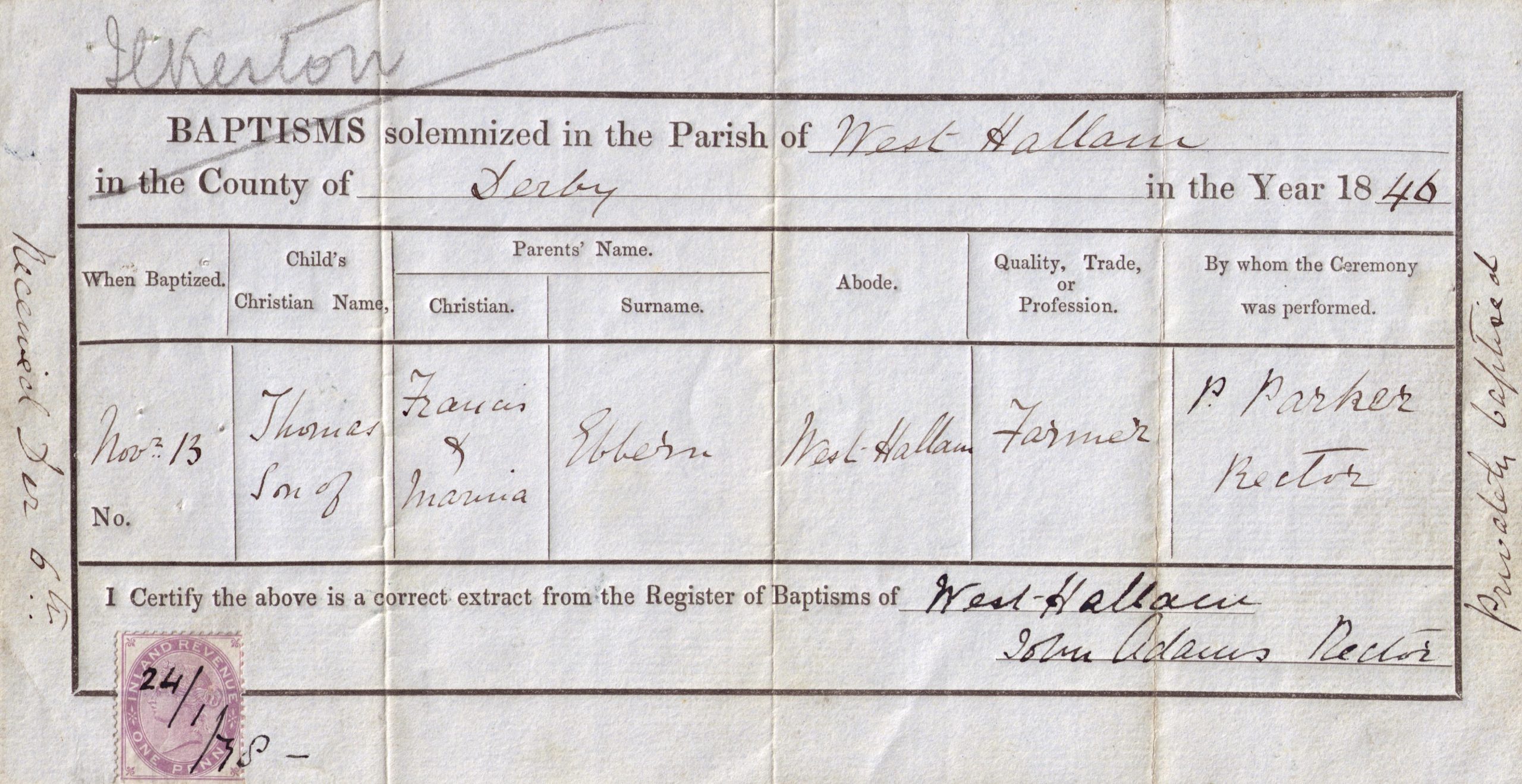

Thomas was the second surviving son …

Birth and baptism …. kindly supplied by Pam Bates

Adeline’s recalls that “Tom married Mary, the youngest daughter of John Birch, joiner.”

We shall see more of Thomas Ebbern on the next page

About 1889 he and his family then emigrated to Canada where they settled in the Marquette district of Manitoba and where other Ebbern children were born.

George Joseph died on February 1st 1937, aged 84, at Ellice, Manitoba.

Frances Amelia gave birth to her illegitimate daughter, Edith Annie, in November 1874 and six years later married clerk Cecil Aldwinkle.

“The youngest daughter became the wife of Samuel Robinson, youngest brother of Robert Robinson, who was schoolmaster at Cossall for many years.”

Born in 1856 Annie Rebecca Ebbern was the youngest daughter who in July 1873 married Samuel Robinson, house painter, paperhanger and plumber, youngest son of William Hallaway Robinson, needlemaker and later coal dealer of Market Street, and Jane (nee Levers).

The Robinson brothers …

Before we look at Samuel Robinson, a quick glance at, first, his oldest brother Robert (1839-1900). He was a National School master for most of his adult working life, at Cossall and then Trowell, but by the late 1880s had large and commodious three storied premises, with a frontage of 20 feet, at 142 Bath Street, between Stamford Street and Brussels Terrace. There he was a dealer in all kinds of musical instruments, as well as holding a large stock of sacred, secular and classical music scores. Pianos were tuned and repaired, and Robert could offer lessons on the piano, harmonium and violin. And he was also a leader of a first class band which could be engaged for balls, private parties, concerts and bazaars.

By March 12th, 1900, Robert had for some time, been under the care of his doctor for heart disease. He was able to walk short distances and was out in Bath Street when he ‘escaped’ into the shop of Edward Smith at number 66, to sit down and catch his breath. And there he died, aged 60.

Another older brother was William (1853-1929?) who started his working life as an iron moulder, his occupation when he married Sarah Ann Pollard on August 8th, 1876. In 1879 he began trading in Market Street as a grocer and off-beerhouse keeper, combining that with house-painting. Unfortunately, by February 1894 he was insolvent, primarily through ill-health. For much of the previous year he had been unable to attend to any work and was severely in debt.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Samuel Robinson at the Poplar Inn 1878-1894

In 1876, as a member of the Church Mutual Improvement Society, Samuel Robinson contributed an essay entitled “Ought Public-houses to be closed on Sundays?”

In late October 1876 Samuel appeared at Ilkeston Petty Sessions, accusing Bath Street grocer and draper (and superintendent of the United Methodist Free Church Sunday School) Joseph Carrier of assault with a dangerous weapon — an umbrella.

Samuel had been engrossed in conversation with Silas Spencer and Edwin Trueman in South Street, when Joseph and his umbrella passed by. The grocer/draper thought that he heard a religious smear spoken by Samuel and intended for him. He was so provoked that he struck the master painter/paperhanger across the right arm with the umbrella, causing serious bruising.

Samuel denied that his remarks were aimed at Joseph and the magistrates agreed that the assault was clearly unprovoked.

The payment of his fine of 10s and 20s 6d costs was immediately forthcoming from Joseph together with a promise not to wield the umbrella against Samuel again.

When he asked what he should do if he heard such remarks again, Joseph was told that the magistrates did not sit there to give advice, nor did they give summonses for ‘sleers’.

Samuel Robinson

In early 1878 Samuel took over as landlord at the Poplar Inn.

In the following year he was placed fourteenth in the celery show held at his inn. There were 15 contestants.

Samuel and Annie Rebecca were at the Poplar Inn in the winter of 1879 when Annie Rebecca’s cousin John Ludlam came to visit.

He was the son of Henry and Jenny (nee Burgin-Richardson) and had recently been keeper of an inn at Motherwell, near Glasgow.

For about two years he had been a heavy drinker, favouring a glass — or several! — of whisky; his brother-in-law Samuel Webster could testify to John drinking 18 glasses before tea-time.

In the last few months he had been wandering around from place to place staying occasionally at the Poplar.

And he was there on Christmas Day 1879, not a merry one for John.

Cousin Annie Rebecca certainly didn’t allow John 18 whiskies before tea-time and he went to bed at about 6 o’clock in the evening, relatively sober but unable to keep any food down and vomiting violently.

Despite medical attention, three days later he died at the inn, from congestion of the liver caused by excessive drinking.

He was 33 years old.

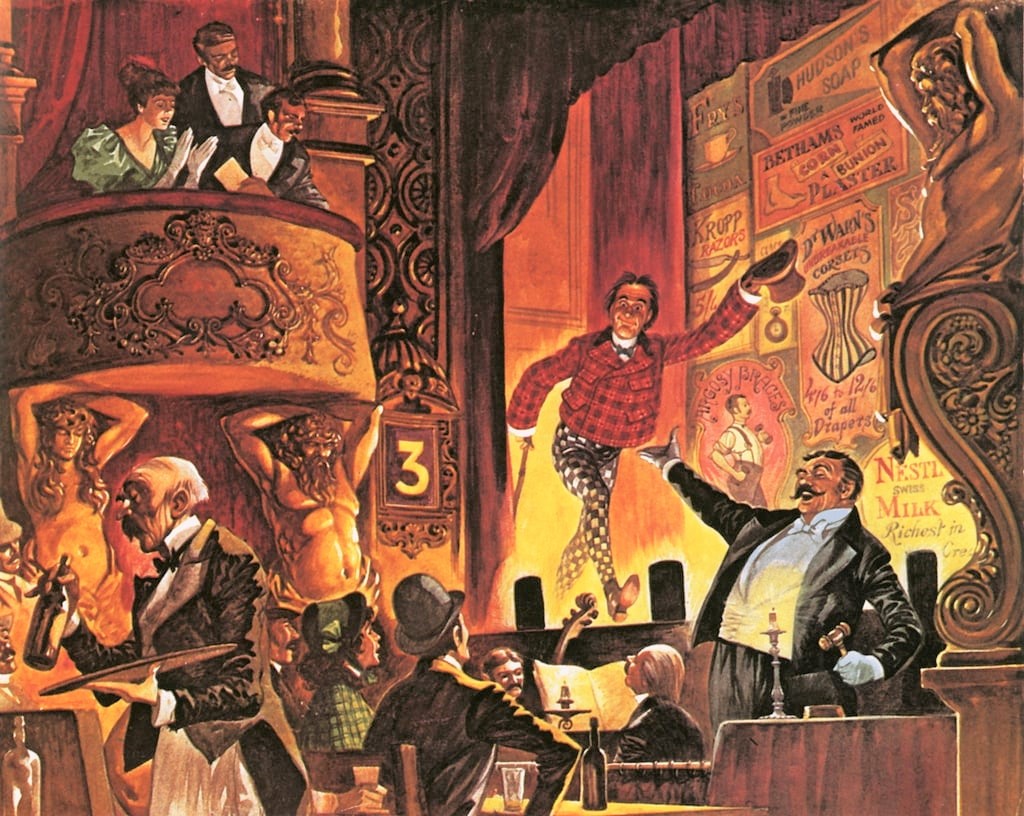

By 1886 Samuel was now the proprietor of the ‘music hall’ at the Inn and was in the habit of pasting posters on a wall near the inn, advertising ‘coming attractions’ at his establishment. Then he noticed that his bills had started to disappear and traced their disappearance to the town bill-poster Harry Tasker Thompson Keeling — Harry had started to pull them down and using the wall for his own ‘official’ posters. Samuel was not pleased and took his case to court — however the magistrates decreed that Harry was entitled to claim the space on this particular wall, and so dismissed the case.

In June 1894 the licence of the Poplar Inn was transferred from Samuel to J. W. Bailey and at the end of that year Charles Bunyan was confirmed as landlord. By April of 1896 John Henry Walsh/Welch is mentioned as being the landlord though the licence was finally transferred by the following July.

Samuel Robinson was elected the ninth Mayor of Ilkeston in 1898 — his appointment was unsuccessfully opposed by Councillor Joseph Scattergood, a member of the Ilkeston Band of Hope Union, on the grounds that Samuel was a licensed victualler and thus was not ‘a suitable person to occupy the civic chair’.

P.S. In February 1897 the Inn’s licence was in the hands of Mark Beardsley when it was transferred to George William Howard, the son-in-law of Samuel Robinson. He kept the Inn until June 1899 when the licence was temporarily transferred to Henry Osbourne

At this time the Poplar Palace of Varieties was owned by Stretton’s Brewery Co. of Derby. In the Spring of 1898 the music hall boasted a brand new stage. The proscenium opening was extended to 19 ft, the depth of the stage to 16ft, and the height to 15ft. The old stage now became part of the auditorium, allowing for an extra 100 folk to be accommodated.

Music Hall entertainment (Peter Jackson)

————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Ilkeston’s first coffee house.

A few months later both Samuel Robinson and Joseph Scattergood were present at the opening, on December 23rd, 1898, of Ilkeston’s first coffee house, the Lord Haddon Coffee House and Restaurant, immediately opposite the Town Railway Station in Bath Street.

In February 1898 the Mayor Samuel Richards had invited a group of gentlemen (sic) who might be interested in establishing a coffee-house company in Ilkeston to meet at the Town Hall. Several Councillors, prominant tradesmen, and representatives of most of the Anglican churches in the town attended, as well as the local agent for the Duke of Rutland, whose wife was strongly in favour of the idea.

So, what was the idea ?

It was proposed to establish an institution to provide light, cheerful and attractive premises, with refreshments of the highest quality and at very reasonable prices … something which the town had long wanted. The wives and children of the working men who came to the market, as well as the men themselves, would be comfortably catered for. On the Duke’s instruction (perhaps with a push by the Duchess ??), his agent had already taken a vacant shop in the Market Place area as ‘headquarters’ but the group was at liberty to decide upon another, more appropriate, property.

The scheme was approved unanimously at the meeting; a limited liability company was to be formed and shares were immediatel bought and allocated.

Extensive premises were secured in Bath Street and Samuel Richards’ son, archiect Samuel junior, was responsible for supervising the building alterations and internal decor.

The Duchess of Rutland, who had been most influential in the formation of the company, performed the establishment’s opening.

However it was her husband who gave the first speech, remarking that “it was of the utmost importance there should be one or more places where people of both sexes could meet together and have refreshments, and partake of ‘the cup which cheers but does not inebriate’”.

With the new mayor/licensed victualler probably standing close by, his Grace diplomatically admitted that he had nothing against those who managed hotels or public houses.

“He regarded as neighbours, and had no antagonism towards, those worthy members of society who invested their capital and employed their intellects in promoting refreshments of a different kind to what they saw in that room for the people among whom they lived” (NG)

The Duke was followed by his wife, a total abstainer, who explained that total abstinence was “good for the health, good for the pocket, and uncommonly good for the temper”.

She too judiciously added that she had the greatest respect for the Church of England doctrine which was not to go in for total abstinence but to allow its members to partake in moderation.

After the speeches “an excellent spread was done full justice to”. .. but no intoxicating liquor!!

It might be that Reuben Shaw — had he still been alive — would argue that this was not the town’s first Coffee House.

The Duchess of Rutland had also been influencial in the success of the Leicester Coffee and Cocoa Company whose aim was to “establish houses, rooms, coffee carts and stalls” around Leicester to provide general refreshment.

As more working men lived in suburbs on the outskirts of town, there was a need for working men’s restaurants in the town centre. Working men would carry their lunch to work and eat it in a public house as there were few other alternatives available. The coffee houses provided hot and affordable food such as “a large basin of nourishing soup for two pence” and “nutritious, comforting and healthful beverages at the easy price of a penny a pint”. Coffee houses were made even more appealing by the fact they were designed to be bright, attractive and comfortable social spaces where both men and women could go, with newspapers and amusements readily available. Some had a ladies’ room and others a billiards room.

East Gates Coffee House in Leicester c 1900

The coffee houses were praised for their “Size, decoration, fittings, cleanliness and order” surpassing “all that was formerly attainable except at high charges” . The duchess of Rutland, opening the Victoria Coffee House in 1888, praised the directors for combining commercial profit with the benefit of the townspeople , stating she “was constantly receiving letters from various parts of the country asking how it was the coffee houses in Leicester achieved such an extraordinary amount of success” . The company went on to set up 14 coffee houses in the town.

Taken from “The Story of Leicester”

———————————————————————————————————————————————————–

January 1899: The “Robin Movement”

At the opening ceremony of the Lord Haddon Coffee House one couldn’t help but notice the crowd of about 100 ‘urchins’ encamped outside and staring greedily in through the windows. One of the directors of the tavern, E.W. Kirk, dispensed buns and coffee to the eager recipients, the food being quickly devoured. This bred an idea in Mr. Kirk’s head which he talked over with Vicar Evans — why not provide a ‘feed’ on a much larger and more sumptuous scale, a “Robin Dinner”?

Naturally a Committee had to be formed and out of it came arrangements to provide for 400 of the town’s poorest children. Tickets were distributed on the basis of “poverty” and no other criteria. This was in the hands of the Church Army, Salvation Army, and other religious groups, and the holders of the tickets eventually turned up, on the afternoon of January 31st, at the Town Hall which was decorated with shields, bunting, garlands and flags. The 410 “Robins” initially assembled in the Market Place where the Boys’ National School once stood, into four long lines, two abreast, each line headed by a flag bearer, the girls behind white flags and the boys behind red ones. All of them seemed dressed in their ‘Sunday best’, washed and ‘sqeaky clean’ for this special day. Members of the town’s fire brigade were on duty in their gleaming uniforms to add a lustre and some ‘awe’ to the occasion, and to marshal the children as they entered the hall. Awaiting them were five long tables, in parallel lines, set with clean white cloths and decked with knife, spoon, fork and mug for each child, and a staff of volunteer helpers to serve the ‘guests’.

Present was Mr. Pochin who had organised “Robin Dinners” in Nottingham for the last 14 years, and he was in charge of keeping order and conducting the flow of events. His way of doing this was by holding up large cards with hugh letters inscribed upon them. The first one read “SILENCE”, (after which the Vicar led off with a musical grace) followed by one reading “FETCH MEAT” — this was the order to send off ‘runners’ to collect smoking plates of beef, potatoes and gravy. Next came the instruction to “FETCH PLUM PUDDING” followed by ecstasy !! After the eating, grace and a few short speeches, a splendid lantern entertainment and then a ventriloquist and conjuror. The event was wrapped up by 7 o’clock and the children ushered out with an orange and a packet of toffee (provided by Job Simpson Derbyshire of Nottingham but born in Ilkeston) to accompany each of them.

The cost of the event was paid for out of private donations,and there was an ample residue to be carried forward to next year’s “Robin” dinner. Would there be one ??

———————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Traffic warning! 9.30am March 24th 1881.

The light trap occupied by pork butcher Gilbert Wilkinson and boot and shoe maker Frederick Mitchell was travelling at speed down Bath Street when, near the Poplar Inn, it collided violently with an omnibus/cab driven by Richard Birch Daykin who had just picked up a passenger at the Midland Railway station.

The trap and its horse were overturned, its shafts broken and the two occupants thrown six or seven yards away.

The shafts of the ‘bus were also broken and the baskets carried on its top were hurled to the ground.

Gilbert was quick to recover but Frederick had to be carried unconscious into the Inn, where he received medical assistance. (… and a whisky chaser?!)

Traffic warning! 11.15pm June 18th 1895

P.Cs Cosgrave and O’Connor couldn’t believe their eyes when they saw two horse and traps furiously having a race down Bath Street, past the Poplar Inn and on towards the Great Northern Railway Bridge on Heanor Road, their ‘Jockeys’ urging on their horses.

In one was Edwin Sutton, auctioneer and valuer of Bath Street, and Town Councillor !!. In the other was Charles Pickworth.

At court Edwin immediately admitted guilt but the charge was dismissed on payment of costs.

Charles however had a tale to tell. He had been proceeding at a leisurely pace, past the Inn when Edwin came by him, leaned over and lashed his horse which then bolted — he managed to stop it only as the bridge was reached.

Conflicting witness evidence allowed Charles to suffer exactly the same punishment as Edwin.

A year (and a few months) later, and still a Town Councillor, Edwin Sutton was back in court defending himself against a more serious charge. And again the Poplar Inn was involved.

On December 3rd 1896 he was at Ilkeston Petty Sessions accused of unlawfully using the Inn for the purpose of betting on horse races. On three separate occasions he had been observed by the police in plain clothes, receiving furtive written messages at the Poplar when the names of various horses were also mentioned. Money changed hands and Edwin constantly made notes in his pocket-book. In his defence much was made of Edwin’s exemplary character and the fact that he had served as a Councillor for the past nine years — but this did not save him from a guilty verdict and a hefty £20 fine, plus costs.

Landlord John Henry Welsh also got it in the neck, for allowing his premises to be used as a betting house. Shortly after this he left to keep a refreshment house in Mansfield but by October 1899 he was a bankrupt with over £500 of liabilities and no assets !!

Edwin Sutton was a man who was very fond of his drink.

It was the evening of April 24th 1898 and now an ex-Councillior, he had visited six public houses in the town, ending not at the Poplar Inn but at the Durham Ox, where the proprietor was Arthur Holmes, himself a town councillor !! It was Edwin’s claim that he was not on a ‘pub crawl’ but had merely been hunting out a bellman to work for him on the next Monday morning — and what better place to look than in a series of public houses !! Arthur however asserted that Edwin was already drunk when he entered his pub; he refused to serve him and Edwin wouldn’t leave when told to do so. He used only ‘the necessary force‘ to evict Edwin. The latter counter-claimed that Arthur, who was a big man, had insulted and assaulted him; he had handled Edwin in his usual bull-dog fashion for which he was noted, tearing his coat collar and throwing his hat across the street.

Where else could this dispute be settled but at Ilkeston Petty Sessions where the magistrate allowed both cases to be withdrawn !!

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

Potter’s Stackyard

We are now just north of the Poplar Inn, at what was called Potter’s Stackyard between the inn and (later) Pelham Street.

This was at the southern edge of ‘Ilkeston Common’, an area which stretched northwards to include Cotmanhay up to about today’s Church Street.

Across from us, on the opposite side of Bath Street is Twell’s Field, at the back of which is the Durham Ox Inn.

In 1873 the stackyard was where the Rutland Colliery Company kept its stacks of hay, straw and clover.

And it was there at midnight on a Saturday in August of that year that a large fire broke out.

The fire engine couldn’t be called as the town didn’t yet have one!!

Three of the stacks were consumed by fire, lighting up the whole of lower Bath Street, and causing excitement and apprehension among the spectators who had gathered. Neighbours rallied around and managed to transport one of the straw stacks across the road and into Twell’s Field.

This was an opportunity for some toe rag to make off with several coats which had been discarded in the rescue efforts.

In the 1860’s and 1870’s the Statutes fair would often ‘slop over’ from the Market Place into the Old Harrow Inn Yard, alias Aldred’s Yard, and at times, move into the Old Stackyard.

In June 1891 a group of eight caravans of wild beasts, housing Biddall’s Menagerie, was parked on this waste ground, when, around nine o’clock in the evening, a fire broke out underneath the stage at the entrance. Inside the audience was watching a performance by a lion tamer — ‘a coloured man’ — and his animal. As the alarm was raised the spectators, including many children, made a dash for the exit, people scampering in every direction. The lion tamer lifted up many of the children and succeeded in removing them to the outside. Once more, bystanders and witnesses, armed with buckets, came to the rescue to quickly subdue the fire. No serious casualties were recorded.

And as a sort of postscript, Andrew Knighton has kindly sent this …

This section on the Poplar Inn refers to the Stack Yard as being a piece of land between there and Pelham Street. I remember well an elderly relative who was born in 1892 and right up until he died in 1987, had a very sharp mind – he could remember events that took place in Ilkeston even before 1900 – telling me about when the annual fair came, the Stack Yard was where the hiring of servant labour and sale of horses took place.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Let’s now have a more detailed look at butcher Thomas Ebbern of Bath Street