Leaving behind Mrs. Boy’s Girls’ school we arrive at “a block of shops below the British School”. The first of these was occupied by ….

John Hickman, draper

(referred to in her article – The Birth of a Street — as Hickinbotham)

On the 1871 census this was 10 and 11 Bath Street.

Nottingham born John Norton Hickman was an unmarried Bath Street draper who came to Ilkeston in the late 1850’s with his parents John, retired butcher and victualler, and Ann (nee Norton).

The 1861 census finds him trading at these premises adjacent to the British School.

Sometime after 1865 John deserted his drapery to convert to publican, for a time keeping the Jolly Boatman Inn on Ilkeston Common.

In April 1867 John Norton was a bankrupt.

The Pioneer of May 1868 noted that he had left the town for Derby and the 1871 census shows him as a farmer in Stirland with his ‘nephew’ Charles Hickman, aged 6.

In the early 1870’s John found his financial problems were increasing and decided to avoid them by moving to Nottingham.

Sarah Ann Norton Hickman was John’s younger – by about eight years — unmarried sister who kept a beerhouse and brewery on Cotmanhay Road in the later 1860’s.

In 1869 a visit to her brewery by the Officer of Excise revealed a small quantity of Grains of Paradise (Aframomum Melegueta) or Guinea pepper, a spice having many culinary uses but also serving as a flavouring for beer or a substitute for malt in the brewing process to give a fictitious strength. Possession of this was punishable by a fine of £200 but Sarah denied any knowledge of its purpose and her brewer, John Leverton, also pleaded ignorance.

The magistrates at the Petty Sessions decided to recommend a lenient fine of only £25.

On the 1871 census Sarah Ann is resident in Cotmanhay Road, as a widowed beerhouse keeper – though she had never been married — with her illegitimate daughter Mary Ann Tomlinson Hickman, born in January 1871 in Ilkeston.

In 1872 she and her daughter left Ilkeston to join her brother. Benjamin Smith took over Sarah Ann’s beerhouse.

In January 1874 John appeared at Ilkeston County Court, being sued by lawyer’s clerk Joseph Clarke for a debt of £6.

Again John pleaded poverty – he was out of work and so couldn’t pay – words which were not in the Court’s lexicon.

He was ordered to pay 5s per month.

In January 1877 and now described as a former draper and publican of Ilkeston, he was appearing at Heanor Petty Sessions charged with stealing 14lbs weight of coal – a lump!! — from Benjamin Howard, agent and manager of Babbington Coal Wharf.

At the court Benjamin declared that he had known John for many years, thought it was John’s first offence, and while he wanted to pursue any thieves, he asked the magistrates to show leniency.

John pleaded guilty and called a character witness who stated that the accused had been his Sunday School teacher.

John was imprisoned for a week.

In May of 1878 it was John’s sister Sarah Ann’s turn to appear at the Petty Sessions – at Ilkeston – charged with having light and unjust weights. Her defence was that she had then only been in business for a couple of months and was thus unaware that the weights were light. The ‘business’ was unspecified and the defence was weak — she was found guilty and fined.

By the 1881 census the Hickmans were in Nottingham where John was a book-keeper and Sarah Ann was still widowed. Nephew Charles was now a son and Mary Ann was a daughter.

And next into the shop was …

Thomas Small

“When he (Mr. Hickman) gave up the business the shop was empty for a long time, until Thomas Small, son of the nurseryman, Mr. George Small, took it, and started as a draper. He had been for some years with Mr. Joseph Carrier, draper”.

In fact Messrs Whitfield Bros occupied the Bath Street store in 1866 until Thomas Henry Small moved into it in June of that year. He traded there until 1884.

George Barker

“Thomas Small afterwards became connected with the Denby Colliery Co., and his one-time apprentice, George Barker, carried on the drapery business.

George Barker married the youngest daughter of Mr. Clay, the landlord of the Mundy Arms”.

We met George Henry Barker in Albion Place.

He was born in May 1854, the son of Albion Place lacemaker Samuel Sargent Barker and Hannah (nee Crooks) and married Sarah Jane Belfield Clay in 1890 – we shall meet her presently at the Mundy Arms.

Draper George Henry moved into these premises about 1884 – before that time he was in Albion Place.

To confuse these shop arrangements, enter George Barker, born in 1841, the son of Albion Place lacemaker Thomas and Mary (nee Mills) and the uncle of draper George Henry.

Uncle George was a haberdasher, a dealer in boots and shoes, and then an accountant, estate agent and — when George Blake Norman retired in 1872 — the Registrar of Births and Deaths. In the 1870’s he was at 10 Bath Street, and stayed there until the mid-1880’s when he moved to Malin House in St. Mary Street.

For a brief period around 1884 the two Georges were side-by-side at numbers 10a and 11 Bath Street.

Uncle George had however given up his shop premises at 10 Bath Street to draper William Flint and continued operating as an accountant at 10a.

In November 1880 William Twells, the step-son of Registrar George Barker, opened his butcher’s shop at 10a Bath Street.

Nephew George Henry acted as the funeral director at the burial of Uncle George in December 1895.

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

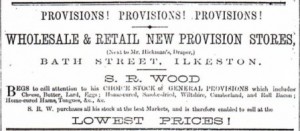

Stephen Richardson Wood, provision dealer

“The next shop was empty until Mr. Wood, provision dealer, took it”. This was 12 Bath Street.

Stephen Richardson Wood, son of tailor Isaiah and Rachael (nee Richardson), opened a new provisions stores in Bath Street, next to John Norton Hickman’s shop, in January 1862. He had a store in Nottingham too.

From the Ilkeston Pioneer of March 1862

By February 1866 he too was bankrupt and left his wife and Ilkeston, citing ‘family grievances’.

He absconded to Brooklyn, New York, on February 9th 1866 only to return in August — to live temporarily in London — when he heard that a petition had been filed against him.

In the meantime and acting upon the advice of the family’s solicitor Hubert Henri Sugg, Stephen’s wife Harriet (nee Rouse) sold off the business’s stock and some family effects, arguing that she had brought many of them with her when she married Stephen and that she was simply trying to claim what was rightfully hers before her husband was forced to give them up. She also returned some furniture to her father as it belonged to him.

In the subsequent bankruptcy court hearing, ‘family disagreements’ were again cited as the cause of Samuel’s transatlantic ‘flight’ and for the sale of the stock — although the Bankruptcy Commissioner suggested it looked more like ‘family agreements’ — especially as Harriet along with the sale proceeds had now temporarily ‘disappeared’.

She was in fact living with her parents whilst carrying on with the Nottingham branch of the business.

After numerous adjournments of the bankruptcy hearing against him, Stephen appeared for the eighth time at Nottingham Bankruptcy Court in May 1867.

By this time the patience of solicitor Hubert Henri with the authorities was wearing thin. (Not a unique phenomenon !!)

When the presiding Mr. Commissioner Sanders asked for the names of the creditors, Hubert Henri curtly stated that they were listed in the balance sheet already presented to the court.

Then the Commissioner wished to examine Stephen’s wife to learn what she had done with the proceeds of her sale. But as she hadn’t been asked to appear at this hearing she wasn’t in court!

She had been there at the previous hearing but the Commissioner had had to leave to catch a train before she could be heard. Mr. Sanders was certain that he needed to speak to Harriet and suggested another adjournment.

Hubert Henri was now clearly exasperated.

Was it really necessary to examine the wife he asked, suggesting that there was no justice in these adjournments to suit the convenience of the court. But the Commissioner seemed adamant that the wife should be produced.

Hubert Henri then pressed the Commissioner on a further point.

HH: “Do you refuse the order of discharge? That is the point in question”.

Mr. S: “You take a very wrong view of the matter. I have not said anything about refusing the order of discharge. You must first show that the bankrupt is entitled to it”.

HH: “If you refuse the order of discharge I shall appeal”.

Mr. S: “You know very well you are not entitled to do so”.

HH: “I shall appeal against the decision”.

Mr. S: “You are pursuing a line of conduct, sir, which you ought not to do”.

HH: “You will not hear my arguments”.

Mr. S: “I have heard quite enough. I shall not pass the examination until the bankrupt’s wife has been examined”.

HH: “Very well. I shall not appear again in the case”.

Case adjourned to June 4th.

On that date Mr. Slater was again present at the court, as was Harriet, as was Stephen…… but no Hubert Henri.

The Commissioner got his wish to examine the wife and was clearly dissatisfied with what he heard, though there was little he could do for the creditors.

The ‘family grievances’ were never fully explained, the sale proceeds had ‘disappeared’ and Stephen was granted a bankruptcy discharge which ‘he did not deserve’.

On the 1871 census the elusive Harriet Wood is living at Alfred Street Central in Nottingham, with her parents John and Elizabeth Rouse but without her husband.

Alfred Burton Wood, provision dealer

Stephen’s brother temporarily managed the Ilkeston business for him while he was ‘absent’ in New York.

This brother was the provision dealer, Alfred Burton Wood, born at Kettering, Northamptonshire, in February 1846 and married to Jane (nee Taylor) at Nottingham in September 1869. She was the daughter of Nottingham optician James Stanley Taylor and Harriett (nee Clarke).

The couple then came to Bath Street on a permanent basis where son Alfred Herbert was born in 1870.

Shortly after taking over from his brother Alfred started to notice that considerable sums of money were consistently missing from the shop’s till. He had his suspicions and was determined to put a stop to the losses.

Consequently one Sunday he made a pretence of leaving the shop to go to Church but returned ten minutes later only to find his shop assistant Samuel Wright about to leave the premises. Alfred accused him of stealing the money and, ordering him to empty his pockets, found seven pennies and two half-pennies which had earlier been marked by the shopkeeper.

At Smalley Petty Sessions Samuel pleaded guilty to theft and was rewarded with three months imprisonment.

In January 1885 Alfred moved from this site, still number 12 Bath Street, into the premises of Isaac Gregory, at numbers 17 and 18 Bath Street — further down the street, opposite the branch of Samuel Smith & Co’s Bank … and later renumbered as 49-51 Bath Street

At this time Isaac Gregory moved out of Bath Street and into Gregory Street.

Alfred Burton Wood was still trading at this Bath Street address until 1898 when he too moved into Gregory Street.

He died in 1910.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Which brings us to William Henshaw, fishmonger