Ilkeston Common

The Holy Trinity Church stood within the Ilkeston Common, the extent of which changed over time and according to which map you might be referencing.

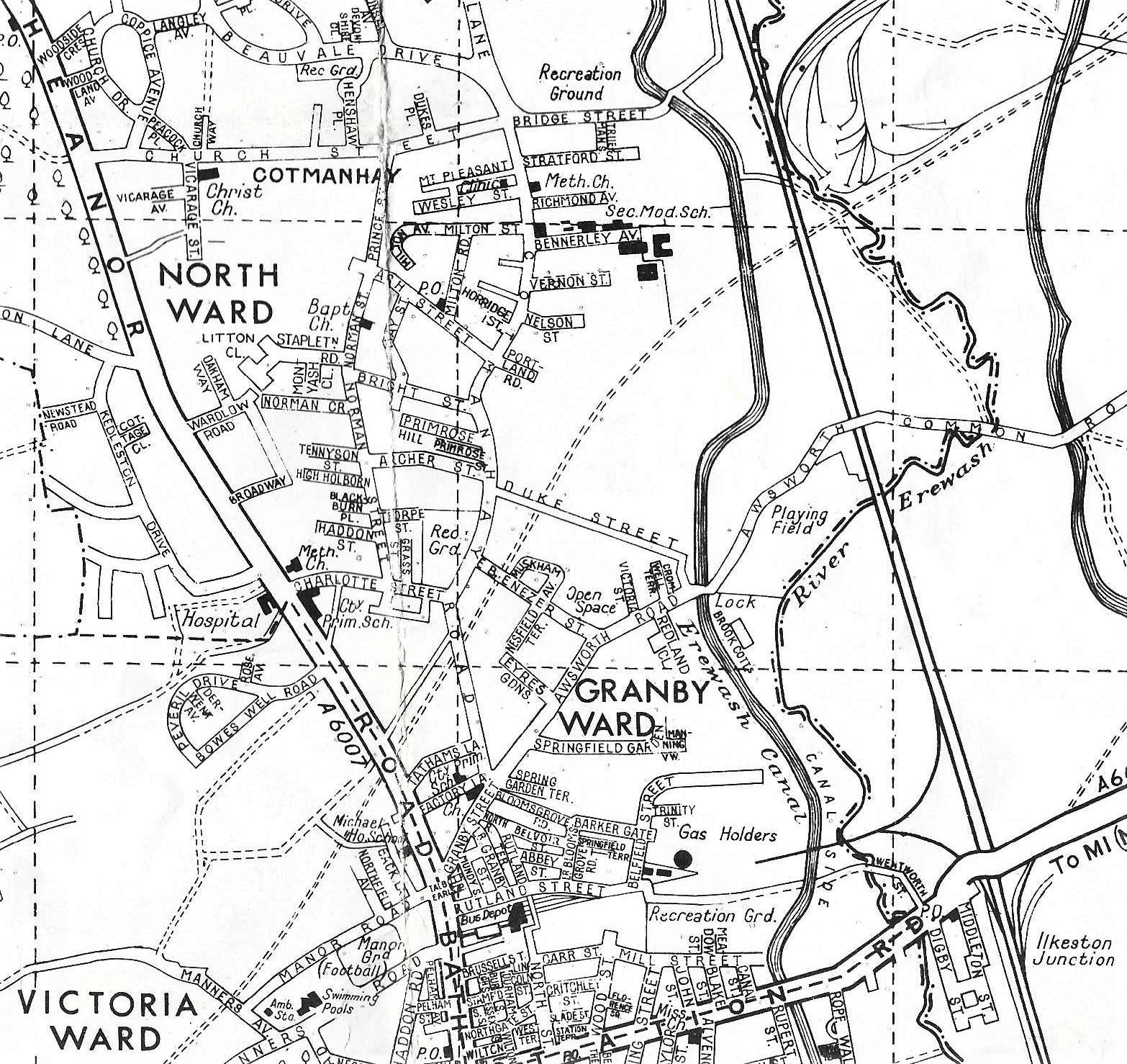

In this section I am assuming that the southern tip of ‘The Common’ started down Bath Street, at approximately the site of the old Poplar Inn. On the map above, that point would be approximately where you see the P.O. at the bottom of the map.

Its western boundary follows the path of Bath Street and what is now Heanor Road, north to Church Street.

Its eastern boundary follows the route of Granby Street and Awsworth Road up to the River Erewash. These roads were known as Coal Pit Road or Navigation Road and were about 40 feet wide up to the bridge over the Erewash Canal. Then they narrowed to 15 feet wide, up to the Bennerley Bridge when the road crossed the River Erewash.

The northern boundary follows the line of Church Street from its junction with Heanor Road, and proceeds eastwards via Bridge Street to the River Erewash. This route was previously called Cotmanhay Road and was 33 feet wide.

————————————————————————————————————————————————

This area was called ‘Common land’ because it was a large stretch of open land where all owners of freehold and copyhold land had rights to graze their animals according to the size of their holdings.

Freehold land was owned absolutely by the owner, who was free to sell it, pass it by will, or settle it, so that it passed to anyone he or she choosed. If no other arrangements were made, the land would pass to the heir of the owner after his or her death.

Copyhold land was technically owned by the Lord or Lady of the Manor. The people who actually lived on and farmed manorial lands were only tenants of the manor. They held their land by custom, which varied between manors. However most copyhold land could be bought and sold, inherited by descendents, left in a will, mortgaged, and settled, just like freehold estates. But every transfer of land had to go through the Lord or Lady of the Manor. The land was surrendered back to them before the new tenant was admitted.

Copyhold land could be converted into freehold land by the Lord or Lady of the Manor. This was done either by including an enfranchisement clause into a deed of conveyance, or by a separate deed of enfranchisement. Enfranchisement transferred the land from the Lord or Lady to the new owner. The new owner paid a ‘fee’ for the transaction.

————————————————————————————————————————————————

We are concentrating upon that part of the Common known in 1863 as Awsworth Road, — as it is today — approaching the old Ebenezer Chapel. In 1893 ‘Bullock-Edge Nook‘ described this area in a letter to the Pioneer

“The neighbourhood…. was perhaps more neglected than any part of the town, for young men in their teens attended the (Sunday) school, and what they there learnt, along with the writing class held on Monday evenings, was all the education many of them received.

“So ill-informed were some of the scholars that the superintendent said, on one occasion, they reminded him of a lad being attended by a doctor, and being told to put out his tongue.

“The lad gazed at the doctor, not understanding him, upon which the lad’s mother told him to open his goblet and put out his lollypop, which the doctor at once examined”. (Bullock-(H)edge Nook 1893)

————————————————————————————————————————————————

On November 12th 1863, the Ilkeston Pioneer was shocked and outraged. Less than a week before — on November 6th — four-year old Joseph Trueman had died from starvation at his Awsworth Road home. The newspaper described the young lad’s home in graphic detail … “a house, containing seven human beings, which did not contain a single article of furniture — no, not even a pillow for its wretched inmates to rest their heads on at night … ragged and sickly children, the best of whose days seem to be over … In the miserable dwelling house, there also died last week an infant, aged eleven months, sister to the deceased”

This sister was Charlotte Trueman, born on New Year’s Eve of the previous year, and during her birth, her pregnant mother had no bed to lie upon. At the end of October 1863, Charlotte developed a violent cough and cold; she was dosed with caster-oil and sweet-nitre but suffered for a fortnight before dying on November 4th. And two days after his sister’s death, young Joseph also died.

The parents were James Trueman, a framework knitter in intermittent employment, and Ann (nee Marriott), who had married on December 1st 1850. James earned 10s 6d a week on average, which had to provide for the parents and five children. They had applied for parish relief but it had been refused, though the whole family had been allowed to spent a couple of months in the Basford Workhouse. The relieving officer then granted them a single payment of 5s, while Samuel Pounder, the surveyor of the highways, found temporary work for James.. On the day after Charlotte’s death, mother Ann received 3s 6d for relief, plus four blankets … for the surviving children ?? (Richard Vickerstaff, collector of the Poor Rates, had vowed to give Ann the blankets from his own possessions if she was not granted them)

An inquest into all these events was held at the Granby Arms on Cotmanhay Road, at which a verdict was reached not designed to make the parents feel any better. “The Coroner observed that this was one of the most distressing cases that had been brought before him for some time. The parish authorities appeared to have done ll that they had been asked to do, as well as the medical attendant, to whom the mother ought to have taken her daughter as soon as it was taken ill. If she had done so, and not allowed some nine or ten days to elapse, the child’s life might have been spared. The only blame, if any, rested with the parents. There was no doubt the girl’s death had been caused by convulsions, and there was as little doubt that the boy had died of starvation.”

However, the Pioneer felt that it knew where much of the blame for these sad deaths lay. Too many professing Christian people, including chapel ministers, were more concerned with attending services, listening to or giving sermons, reading bible texts, or partaking of the Lord’s Supper, and so forgot to act as Christian folk. “One act of charity, meekness or humility, speaks more than a day’s discourse” Why had no-one recognised the obvious needs of this desperate family ?? And as if to rub salt into the wounds of a grieving family, within a few days of the inquest a third child — two-year old Sarah Ann Trueman — also died.

Of course the religious community was quick to express a rebuttal of the accusations. The Vicar of St. Mary’s Church — the newly-arrived James Horsburgh — took only a week before he had fired off a letter to the Pioneer. Referring to the inquest testimony of the doctor, the Trueman parents and his own personal knowledge, James categorically stated that no member of the Trueman family had died of starvation. He had had contact with that family before the tragic events and had arranged a loan of money to the mother, who had later insisted upon paying part of it back — ” Can any thing be more convincing than this, that the Truemans had enough and to spare?” The father had insisted that the children never hungered; “It was the house we were in did it”.

The newspaper had suggested setting up a system of regular ‘house-to-house’ visitation to detect need. Not without a hint of sarcasm, James asked that the newsapaper might“give us a hint where the goose may be found which will lay the golden egg for the ‘supply of the wants of all the necessitous’ in this large place ‘once every month’ .

1891: Mayhem in Granby Street

Robert James Pratt was a young man who arrived in Ilkeston from Mansfield about 1870, to be an assistant to chemist William Fletcher at his shop, next to the New Inn at Providence Place. Twenty years later he was a married man, with four children and managing his own branch shop in Granby Street.

The weather on the evening of June 2nd, 1891 was particularly inclement — rain fell in torrents, followed by hail and vivid lightning. And one terrific peal of thunder announced that Robert’s home had been struck by the lightning, severing its front chimney stack, which fell into the street — and quickly followed by the back chimney stack. The chemist was in bed at the time, suffering from ‘flu, and could only watch as plaster fell from his bedroom ceiling, soot covered his furniture, and lightning passed through the house.

William Fletcher’s son, Fred — the well-known bicyclist — was serving in the shop at the time, and quickly scarpered into the street, thinking that the building was collapsing.

No-one was injured.

————————————————————————————————————————————————

Let’s now wander, just across the Awsworth Road, to visit another family living on the edge of Ilkeston Common — the Howe family