(This page is in preparation and is just a rough draft)

Town amusements.

“Amusements were very few. There would be a party or two at friends’ houses at Christmas time, and perhaps a concert in the Cricket Ground chapel…. but it rested on the mother to keep her children interested and entertained during the long dark winter evenings”. (Adeline)

Born in 1864, writing in 1933 about life in the 1870’s, Richard Benjamin Hithersay agreed with Adeline’s short assessment.

The monotony in the town would be broken by the annual Flower Show, the ‘Wakes’ and the ‘Statutes’, outings associated with religious bodies and an occasional concert in the Town Hall, though the ‘busy and often rowdy’ Market at the end of the week offered a welcome change to many.

‘Those who wanted music-halls, theatres, or ‘life’, as it is generally understood, had to go to Nottingham or Derby to gratify their aspirations. Cheap railway return tickets on the market days of these respective places enabled them to do so at small cost for transport, and the exodus from Ilkeston on these occasions was always very big’.

Amusement centres of occasional attraction included the Old Harrow Inn yard, Woodroffe’s Croft, the ‘Junction’ and the Cricket Ground.

In September 1893, Henry Vincent Clarke was granted permission by the magistrates to build a theatre on Rutland Street to accommodate 1200 persons and to be made of wood.

The Harrow Inn Yard attractions

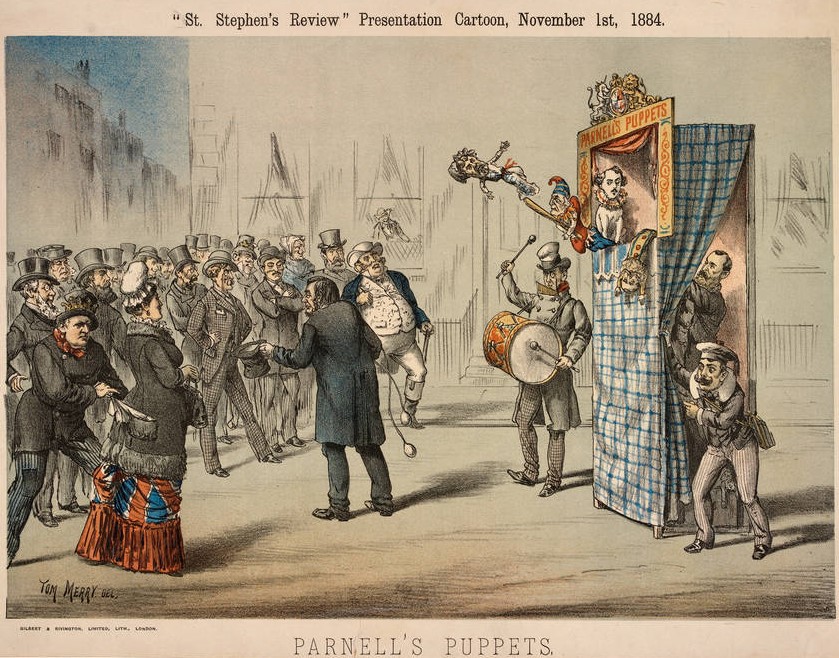

The Inn’s spacious yard — now taken up largely by St Mary Street (above) — adjoined the house in the rear and here many activities took place and attractions appeared. In fact anything in those days was considered an attraction by the boys, from an auction van to a marionettes’ display.

Theatre and drama

————————————————————————————–

One such ‘lure for the lads’ was Tom Payne’s travelling theatre.

Its members would perform “modern” plays like ‘The Corsican Brothers’ (by Alexander Dumas 1845) and ‘The Colleen Bawn’ (a tale of love and intrigue by Dion Boucicault, 1860), as well as many old fashioned dramas like ‘Maria Martin, or the Murder in the Red Barn’, a melodrama based on the true story of the murder of a young girl in 1827.

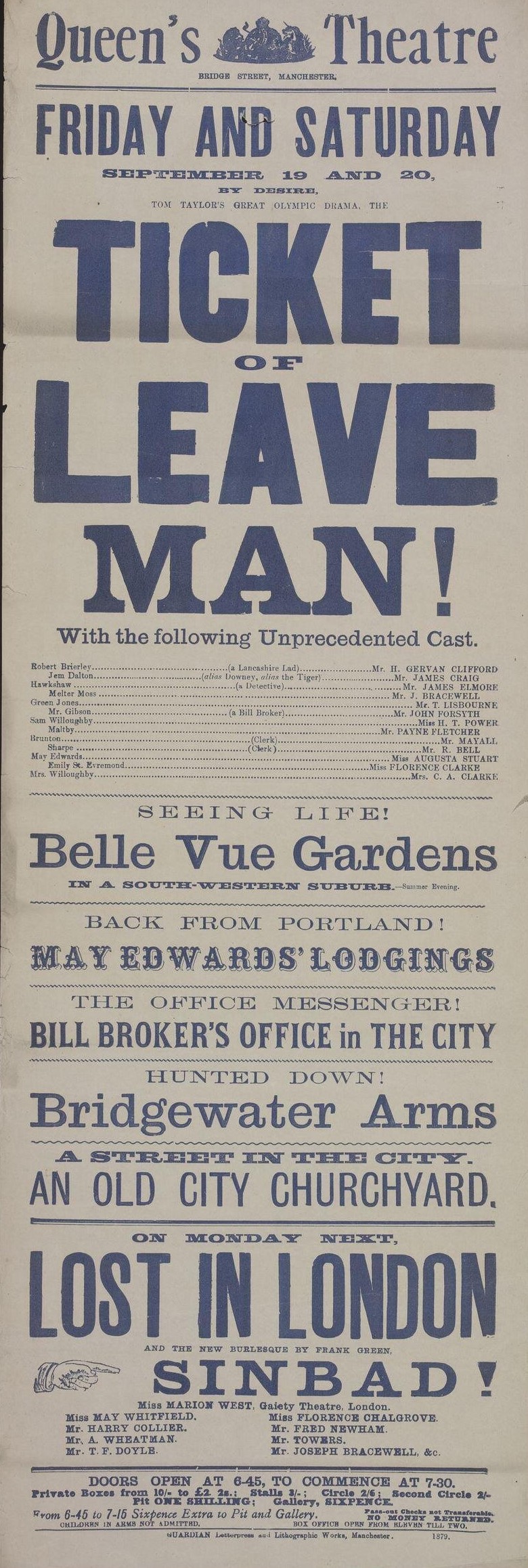

Sheddie Kyme recalls ‘The Ticket-of-Leave Man’ by Tom Taylor (1863) and that venerable fossil ‘Ingomar’ (1851), a romantic drama by Austrian writer Friedrich Halm.

Dangling high in the ‘gods’ of the theatrical troupe’s temporary tented theatre, he and his mates would enthusiastically cheer that ‘beautiful sentiment’…

‘Two souls with but a single thought, two hearts that beat as one’.

Ilkeston had its own, real-life, ticket-of-leave man in the form of Thomas Garrett whom we shall meet later.

Games

Another attraction for the local lads was any opportunity to win a few ‘chance’ pennies.

For example, in October 1874 Tom Brooks brought his game of Two Pins to the yard and challenged the assembled group of juveniles to knock both pins down with one ball. A Penny a Go !! He persuaded several lads to try their luck and they obviously hadn’t realised that the pins were sufficiently far apart to make the task impossible.

When he was arrested for gaming he had seven or eight shillings on him – that is enough pennies for up to 96 ‘Goes’.

Tom spent the next month in jail.

Pedestrianism

Sheddie Kyme again:

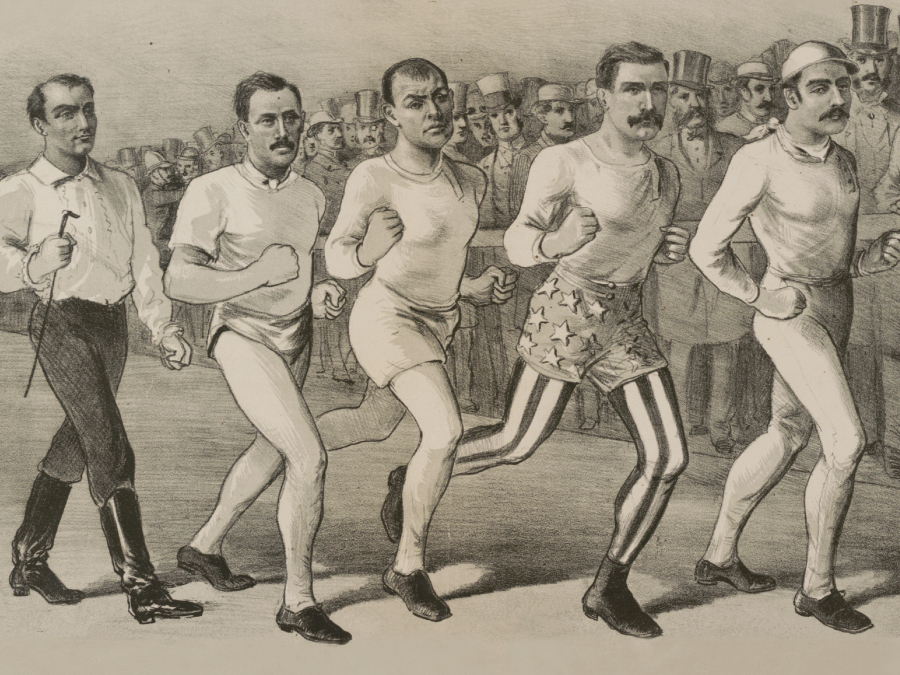

“There was a time when the Old Harrow yard was notable for pedestrianism. Professional handicaps in Mr. Joseph Aldred’s day were very frequent and attracted many people. Some of the sprinters, I remember, in addition to Mr. John Tilson (alias Bellows), were some of the Eatons, including ‘Spanker’, who, I believe is now at Southwell, and William Spencer. Professionalism was more to the fore in those days, and much money would change hands in stakes on the various heats. I believe it was in this cinder track that Spencer first made his appearance as a sprinter, but he afterwards succeeded in securing one of the Sheffield handicaps, as many Ilkestonians will remember”.

‘Spanker’ was possibly twisthand Ezekiel Eaton, the son of framework knitter Edmund and Ann (nee Winfield) whom we shall meet in Extension Street. Ezekiel left Ilkeston with his family in the later 1890’s to work in Southwell.

And from the Nottinghamshire Guardian, August 1876, under the heading ‘Pedestrianism at Ilkeston’.

“On Monday a walking match took place at Mr. J. Aldred’s Recreation Ground, Market-place, Ilkeston, in which Frank Bradley (Perkins’ novice), of Nottingham, undertook to walk fourteen miles in two hours. The ground measured was 200 yards round, and 122 laps were required to make up the fourteen miles.

“Bradley started at 6.53 p.m. and completed the first seven miles at 7.49¾, or 3¼ minutes under the hour. He continued walking at a good pace, but when he had completed 31 laps of the remaining 7 miles it was almost dark, and as he complained of his feet being sore he was persuaded to relinquish the task at 8.23 p.m., having completed 10 miles 911 yards in one hour and a half. When he had eleven laps of the first seven miles to walk George Williams, of Ilkeston, started to walk seven miles with him, and continued after Bradley left the ground, our parcel being despatched before the result was known.

“On Saturday evening last Bradley undertook to walk 7¼ miles in one hour for a bet of £25, which he managed to complete with one minute to spare”.

The Wakes and Statutes

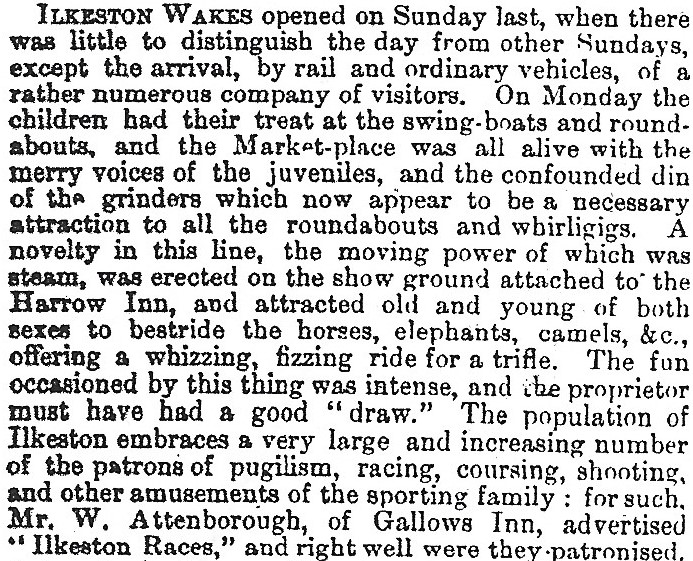

And of course, we should not forget Ilkeston Wakes, occurring every year at October time ….

Writing in the Ilkeston Advertiser (April 28th 1933) about Ilkeston 50 years before, Richard Benjamin Hithersay (RBH) dismissively and not entirely accurately wrote “Those who wanted music-halls, theatres, or ‘life’ as it is generally understood, had to go to Nottingham or Derby to gratify their aspirations. … In the town itself there was nothing to break the monotony beyond the annual Flower Show, the ‘Wakes’, and the ‘Statutes’ — functions which were ceratinly very lively, and which attracted many hundreds from the surrounding villages. Apart from these, the ‘outings’ associated with the various religious bodies and an occasional concert in the Town Hall constituted about all the recreation available for the Ilkestonian of 50 or 60 years ago”.

The Junction.

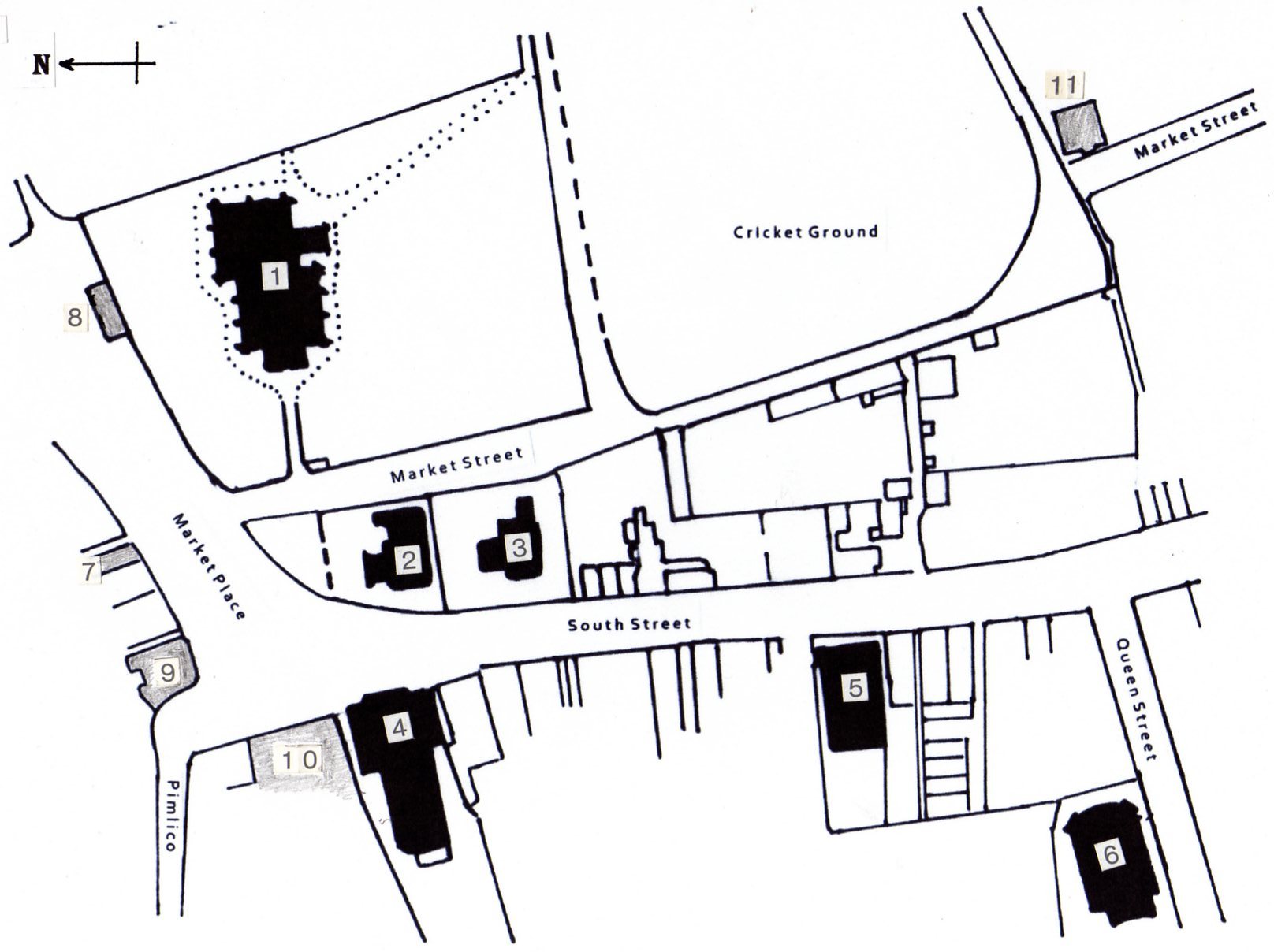

In a letter to the Pioneer, dated September 8th 1870, an Old Ilkestonian complained that a new schoolmaster’s house for the two National Schools located in the Market Place was to be built “on the Junction in the Market-place beween the two schools”

This would place it between the two sites labelled 2 and 3 on the map (right). A detailed key to the map can be found here.

In the same letter, the writer suggested that “the Junction ought not to be appropriated to the erection either of schools or cottages, but for markets, fairs and other public purposes”

The ‘Junction’ was also the area chosen by Noakes’s itinerant theatre when it made frequent visits to the town in the 1860’s, eschewing Aldred’s Yard. There it set up its tent, inside which the audience, seated on bare boards and enduring a keen wind through the canvas, spent an enjoyable evening at the ‘Rag show’.

“I can well remember being taken to Noakes’s show by my father on a particular night, probably in 1859, when the play was ‘Three-fingered Jack’, and I heard sung for the first time that good old-fashioned song I should like to hear again, ‘Ever of thee fondly I’m dreaming”. (Old Resident)

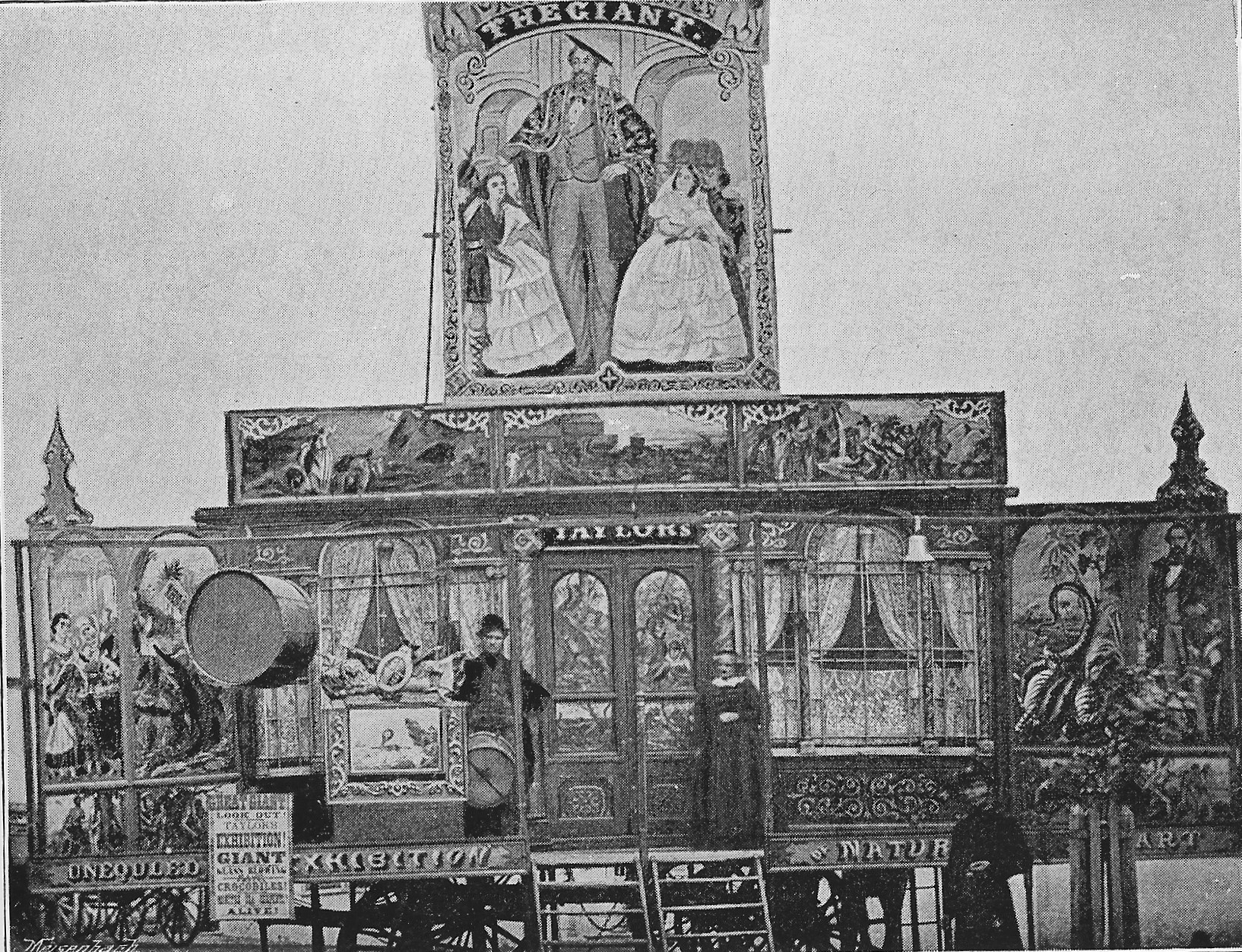

And the same writer cast his mind back again, to 1860, or thereabouts when for several winters in succession Ilkeston was treated to “the exhibition of Samuel Taylor, the Ilkeston Giant (which) was located on the ‘Junction’ for three or four months. During that time his horses were utilised in doing team work for the Stanton Iron Co., which was a very modest concern then …

“The ‘show’ was open two or three times a week, and was well patronised. The programme consisted of glass-blowing by Mrs. Taylor (who looked like a pygmy when standing beside her husband), the showing of a number of more or less wild animals, followed by dissolving views mainly descriptive of the Crimean War, and last, but not ‘least’ by any means, by the appearance of the giant himself. His height was 7f.t 4in. and the ‘tallest gentleman in the company’ was always invited to come forward and stand beneath his outstretched arm. Most of my spare pennies – and they were very few in those days – went into the giant’s coffers … This remarkable man is buried in the Stanton-road cemetery, Ilkeston, where there is a handsome granite monument over his grave”.

At the time of Samuel’s death, in 1875, the Ilkeston Pioneer gave a few details of his years before …

He was born in Little Hallam in the year 1816. Son of a farmer, he stood 6’9” in height, his own mother being only 5′. His father died when he was 18 months old, so his mother had to provide for the family.

Due to his extraordinary height, he found it difficult to obtain a situation in his native village. One day he visited the Castle Donnington Statutes, offering himself there for a situation. A giant was being exhibited in a show there, and as Samuel had never seen such a show before, he paid his penny to see the man. (Judging by the painting on the outside of the van, he expected to see a man about 14′ tall, and much larger than himself.)

In Samuel’s own words, “I entered the exhibition — a curtain was drawn — and I discovered a man about 6’3”. All eyes turned on me, I stood beside the giant and made him look insignificant. He did not seem much to like the comparison. When I was leaving the showman tapped me on the shoulder and asked if I would accept an engagement to travel, and be exhibited as a giant. I laughed at the idea”. However the offer was so good that Samuel accepted the situation…”

And the rest is history.

Samuel Taylor’s Exhibition (from Trueman and Marston)

Samuel Taylor’s Exhibition (from Trueman and Marston)

Another visitor to the exhibition was Sheddie Kyme who concurred with much of what Old Resident could remember and added an up-to-date magic lantern display, two reptiles and a crocodile.

‘Tilkestune’ (IA 1929) recalled the show’s waxworks and the Giant’s brother, who exhibited some enormous snakes at the front of the show, where Samuel “stood in the doorway and everyone who entered could go under his arm…. Taylor was so tall that he harnessed his horse completely while standing on one side of it. He simply bent over the animal while fastening the harness on the other side”.

Samuel Taylor (from Trueman and Marston)

One day in early 1875 while packing up his show at Oldham, Samuel slipped from the roof of one of his caravans and later died from his injuries.

“I well remember the news reaching the town of Sam Taylor’s death, and Ilkestonians were generally pleased to learn that it had been decided to inter his remains in the town of which he had spent, at any rate, a great portion of his younger days….

“….. So the career of one who had played a prominent part in the Statutes of Ilkeston for many years, was brought to a close”. (Sheddie Kyme)

Though the exhibition did not die with Samuel.

It was remodelled “on more modern lines, a mechanical arrangement, representing a storm at sea, being the principal feature. This disclosed a ship in distress, going to pieces, as it were, on the rocks – and all to the strains of ‘The White Squall’, that song which sets forth so realistically, the roll and pitch of the vessel, as it rises and falls with the billows”.

The Pioneer described this area as a temporary home for ‘the filthiest exhibitions, designated shows, shooting galleries, steam screeching roundabouts, and caravans innumerable’. (1882)