We have just walked past Joseph Carrier’s premises and are now approaching what is, today, the Borough Arms site (if it’s still called by that name ??). Of course, if you think about it, you wouldn’t have found the pub with that name prior to the Incorporation of the town in 1887 … and even a few years after 1887, as we shall see.

Now we are going to examine the history of this part of Bath Street during the 100 years before this. And beware … it’s quite a complicated story where souces are unclear and contradictory.

But first ….

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Freehold land was owned absolutely by the owner, who was free to sell it, pass it by will, or settle it, so that it passed to anyone he or she choosed. If no other arrangements were made, the land would pass to the heir of the owner after his or her death.

Copyhold land was technically owned by the Lord or Lady of the Manor. The people who actually lived on and farmed manorial lands were only tenants of the manor. They held their land by custom, which varied between manors. However most copyhold land could be bought and sold, inherited by descendents, left in a will, mortgaged, and settled, just like freehold estates. But every transfer of land had to go through the Lord or Lady of the Manor. The land was surrendered back to them before the new tenant was admitted.

Copyhold land could be converted into freehold land by the Lord or Lady of the Manor. This was done either by including an enfranchisement clause into a deed of conveyance, or by a separate deed of enfranchisement. Enfranchisement transferred the land from the Lord or Lady to the new owner. The new owner paid a ‘fee’ for the transaction.

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

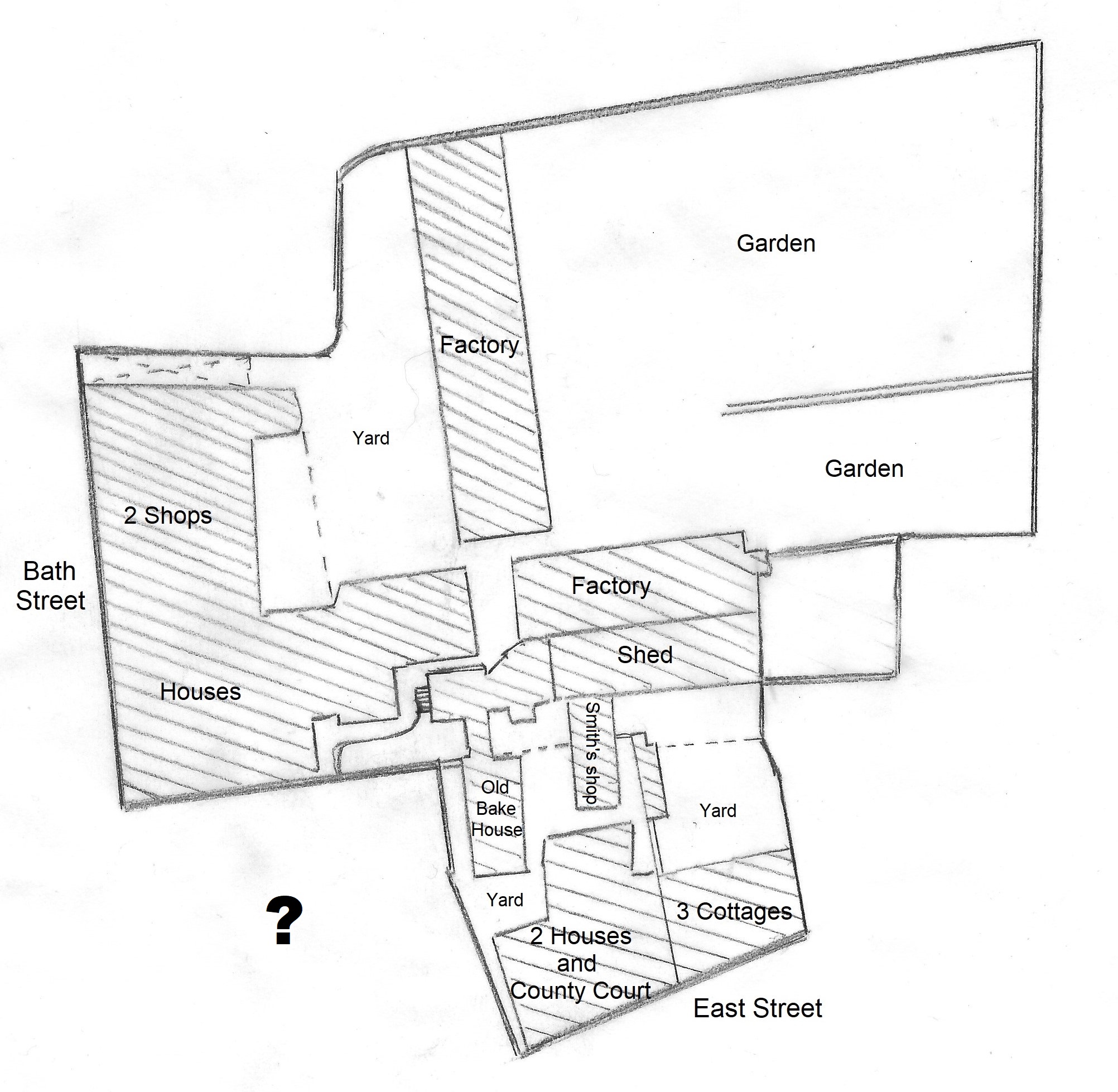

We have seen this plan, above, previously … it shows the Carrier properties in 1901. You will notice that as we walk up along Bath Street, past the alleyway leading into the Carrier factories, past the two shops and houses, there is a section of the plan, at the confluence of Bath Street and East Street which is unidentified …..at ? Then, as we walk down East Street, we come again to the Carrier property.

What is the history of this corner ?

We know that this was a block of land that did not belong to the Carrier family — part of which is where the Borough Arms later stood. This contained copyhold property which was enfranchised in 1886 by James Shipstone who had purchased the area from George Small’s devisees in 1885. But before 1885 ?

—————————————————————————————————————————————————–

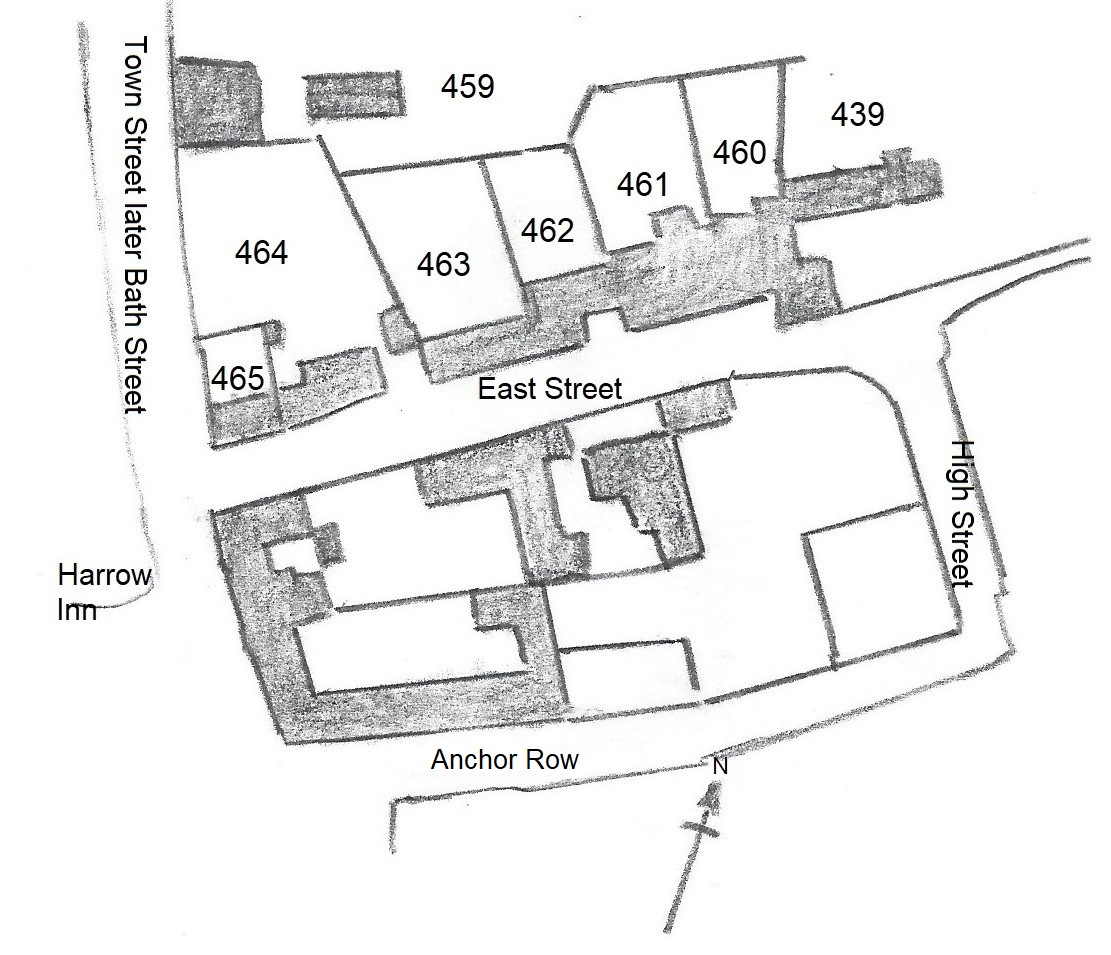

The map below is adapted from William Gaultley’s map of Ilkeston, 1795, in which the mapmaker showed the copyhold premises in parcels and numbered them, gave some detail of their houses and who occupied them. (The shaded areas are buildings of all sorts). As we are only concerned, at present, with those at the conjunction of Bath Street and East Street, those are the parcels I have numbered.

A sketch taken from William Gauntley’s Map of Ilkeston of 1795

At that time and on the corner — at parcel 465 — was the copyhold house, shop and garden of Thomas Stoppard, inherited from his grandfather Moses Stoppard, and which later also contained a stone quarry. It was hemmed in on both its north and east sides by another copyhold property — parcel 464 — belonging to Michael England. He was a butcher and had taken possession of these premises in 1786 and 1787 from framesmith John Woollin and his wife, Hannah (nee Barker).

Some of the property of Michael England — a single messuage, its yard, stable and part of its garden — was transferred to John Pedley, an Ilkeston miller, in two stages, in 1800 and 1804. It also appears that some buildings and part of the garden of England’s property was taken over by Robert Henshaw, although this conflicts with some sources. In 1804 a further part of England’s garden was again taken by John Pedley — it was bounded on the east by the other part of Pedley’s garden (taken in 1800); in the south by the buildings belonging to Robert Henshaw; in the west by Town Street (Bath Street); and in the north by buildings belonging to John Shaw (in parcel 459)

In 1817, Stoppard’s ‘corner tip’ (465) was now owned by the heirs of tallow chandler Richard Potter — he had acquired this from a Trowell butcher, Samuel Walker, who had left to live in Calverton. (Samuel had acquired it from Thomas Carrier in 1804, who had acquired it in his father John’s will of 1793 etc. etc. )

In 1826 John Pedley died and left all his estate (in 464) to his niece Fanny Potter, daughter of Thomas Potter of Mackworth. A month after John’s death, Fanny married Thomas Buxton, a bricklayer of Allestree, Derby at St. Mary’s Church. In the following year Fanny and her husband sold the inherited estate to butcher William Fitchley (who appears in possession of it on the 1841 census). By this time the property of John Shaw in parcel 459 and north of the former Pedley estate, had been transferred to Samuel Potter.

Then, in 1830 Richard Potter’s ‘corner’ property (in 465) went to the same Ilkeston butcher, William Fritchley, who sold it to seedsman George Small about 1835 — and we can find George there on the 1841 census.

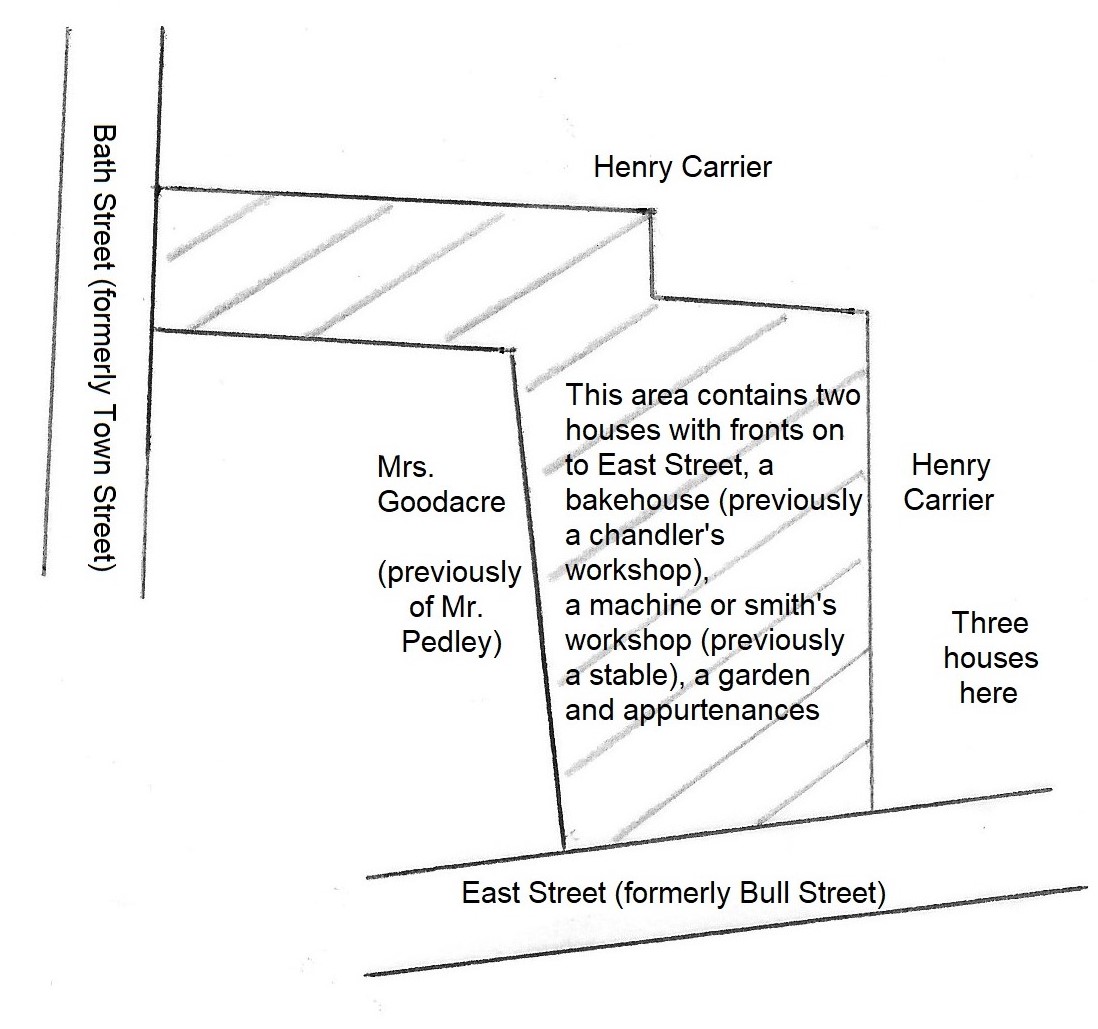

In 1843 William Fritchley sold his land (in 464) to Ann Goodacre, wife of Richard Alwood Goodacre and the daughter of Humphrey Whitehead of Trowell. (Within three months Ann was a widow). It was now described as being bounded on the north by part of a garden belonging to Samuel Potter; on the east by a house and garden, belonging to the same Samuel Potter; on the south by East Street; and on the west by Town Street. The land now contained a stable and three houses — two which fronted onto East Street and one at the rear. The first two were subsequently occupied by cordwainer William Rose, who had come to Ilkeston via Manchester about 1845. He was married to Mary Ann Walker in 1843, daughter of Ilkeston postmaster and shoemaker Paul Walker and Eliza (nee Varley) — the Walker family lived just across the street. You will see William Rose and his family in East Street on the 1851 census. The house at the rear and the stable were occupied by Thomas Sowray, excise man. Thomas was not in town on the 1841 census although, interestingly, this house was occupied by Samuel Mitchell, also an excise officer — was it a building reserved for such men ?? A tax office ?? (It should also be noted that William, the father of William Rose of this area was also an ‘excise man‘ — did he occupy this same house at one time ?)

Meanwhile Robert Henshaw had died in 1842. Some of his property (in 464) appears to have been in the hands of Samuel Potter by 1849 and was sold to Samuel and Joseph Carrier in 1851 and enfranchised by them in 1855. This is the part which fronted onto East Street and is shown below…. the same sketch as Plan 2 (previously)

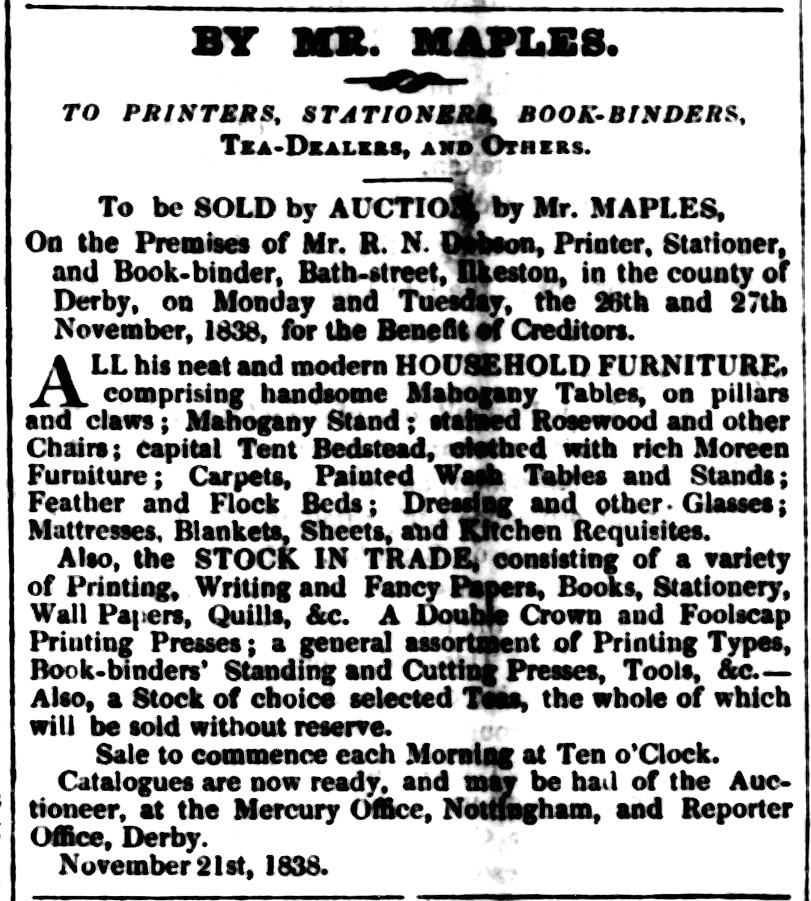

However Henshaw’s plot (in 464) extended north and westwards so that part of it fronted onto Bath Street — and on this part he had erected another house and shop. These premises were occupied by schoolmaster/printer and stationer Ralph Ness Dobson and his family; when they left Ilkeston at the beginning of 1839 in came John Wombell, also a printer.

Ralph Ness Dobson sells up (Nottingham and Newark Mercury, November 24th, 1838)

In 1846 he bought it from Robert Henshaw’s widow Ann. (Robert died in 1842 remember). This later became the New Inn.

On another part of the same land Robert Henshaw had erected a second house to live in, and this was later used by tinman Eliezer Pickburn.

In 1858 the Bath Street property purchased by John Wombell in 1846 was surrendered to George Small — John was moving into the Market Place. And this left George Small owning most of this corner.

In (tentative) conclusion therefore, walking past the shops of Joseph Carrier, we would then pass the premises at one time occupied by Ralph Ness Dobson (in 1838), then by John Wombell until he sold them to George Small in 1858. Then we would pass the New Inn and the corner seed shop of George Small, before walking around the corner into East Street where the shop of George Small would continue.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————

So, now is the time to drop in on John Wombell