Walking from the Shaw family in this area, (at least for a while) we come across …

A boiler explosion ?

Adeline remembered that “at the end of New Street in Burr Lane, was a field which led to the old Slack Road, and over the branch line into another field that finished on the Common, opposite Cotmanhay Road. In the lower field there was for many years part of an old iron boiler. My father told me that there had been an explosion that caused the boiler to lie there. I forget where the explosion had been.”

A possible candidate? .. though a bit too late?… and too distant? ….

“On Tuesday afternoon (July 3rd 1877) the inhabitants of the northern end of Ilkeston were startled by hearing a loud report, which was found to be occasioned by the bursting of a boiler at the brickyard of Messrs. Hewitt and Tutin, situate in a field near to Station-road. Both ends of the boiler were blown out, the top of the boiler house was taken off, and the engine chimney knocked down. Fortunately the men and boys at work were underneath the brick sheds, so that no person was injured. Pieces of brick and other debris were hurled a considerable distance, and the consequences might have been much more serious if the locality had been thickly populated”. (NG)

______________________________________________________________________________________

Dr. Norman’s premises

Adeline recalls that ….. “there were no houses down New Station Road, except Norman’s old Farm House in a field on the south side leading up to the Park and Hilly Holies.”

An Old Resident recalls that between the end of New Street, just past North Street, and Cossall Marsh, there were no houses except Mill House occupied by the late Mr. W.S. Adlington, J.P., and two or three old cottages.

In 1881 Mill House was occupied by mining and civil engineer Maurice Deacon and his wife Adelaide Eliza (nee Bazeley) and was part of the late George Blake Norman’s estate. It included a mill which in 1881 was fitted out as a flour mill but could be adapted for plaster or cement, and stood equidistant from and between Station Road and the Midland Railway line running into the Town Station at the bottom of Bath Street. Its site was approximately at the western end of what was soon to become Mill Street.

Norman Cottage or Norman House is recorded on the 1851, 1861, 1871 and 1881 censuses, as the enumerator listed Burr Lane and Albion Place.

In 1851 there were three households occupying ‘Norman Cottage’ — Cossall-born labourer Phillip Tarlton and his family: railway porter Joseph Rusby, his wife Mary (nee Clarke) and his niece Mary Ann Hinde: Ruth Truman, widow of Thomas, and her grandson William Severn Trueman, illegitimate son of her daughter Ann.

In 1861 Norman Cottage was occupied by Elizabeth Dixon (nee Needham), widow of George Smith and then of coal miner Samuel Dixon. She was with her youngest child Mary Ann Dixon, aged 14.

At Norman Cottages were the two families, of journeyman miller Richard Daubney and of Philip Tarlton.

In 1871 the family of colliery labourer James Eyre was at Norman’s House.

In 1881 colliery carpenter Joseph B Hackett and his family were at Norman Cottage.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Benjamin Howard and family

According to Adeline …. “on the canal bank, towards Evan’s Potteries, were a couple of old cottages. Mr. Howard lived in one.”

Born at Hempshill near Bulwell in 1810, Benjamin Howard was a son of Thomas and Martha (nee Kettleband?).

He worked as a lacemaker at Stapleford until he left there in the mid-1840’s to come to Babbington Wharf as a coal agent/manager at the wharf. (This wharf was opposite Wash Meadow on the eastern side of the Erewash canal).

Already married to Harriet (nee Allen) and with several children, Benjamin added to their number after his arrival in Ilkeston.

Benjamin’s wife Harriet died suddenly one Saturday afternoon April 1876 as she sat down to tea at their Canal Side home — aged 68.

Benjamin senior converted to smallware and hosiery dealing in the later 1870’s and by 1878 was trading at 88 Bath Street – just south of Station Road and almost opposite the New Inn. He died at his Bath Street home on April 29th, 1897, aged 86.

______________________________________________________________________________________

The six children of Benjamin and Harriet Howard

“The Howards had two sons. Ben the ‘Orator’ and Alva, and three daughters. Martha, who was a pupil teacher at the British School, under Mr. Holroyd. The second became Mrs. Henry Smith. Jane remained at home.”

The one child not recalled by Adeline is the eldest one, Thomas the engine driver, who left the town in the 1860’s and moved eventually to Nottingham with his wife, Ilkeston-born Mary (nee Woodward), daughter of labourer William and Ann (nee Reed).

Eldest daughter Sarah was the second wife of Henry Smith whom she married in 1875 (see the tale of George Clay Smith). At the end of the century and thereafter they lived at 5 Gregory Street.

Martha married hosier Samuel Cresswell – also a one-time pupil teacher at the British School in Bath Street — son of boot and shoe maker George and Eliza (nee Skevington), in 1865. The couple then moved to Nottingham and thence to Sandiacre.

Adeline has pointed out earlier that Sam Cresswell was a senior employee of Henry Carrier & Sons, of Bath Street, Ilkeston and Nottingham. The firm’s Nottingham warehouse, where Sam was eventually to work, was situated at the end of the cul-de-sac known as Mount Pleasant Yard off Mount Street, and by 1896 had been used by the firm for about 50 years. It was 16 windows long, three stories in height in one part, though a fourth storey had been added over the majority of the building. It employed between 40 and 50 hands, mainly women, and acted as the firm’s warehouse and saleroom, the principal factory being at Ilkeston.

On Thursday morning, May 28th, 1896, a fire broke out at the warehouse leaving an almost completely demolished building and damages estimated at £10,000. A local resident was the first to discover the fire, raised the alarm, so that the Borough Fire Brigade with two steamers was quickly at the scene. The combustible nature of the factory’s contents meant that it was impossible to stop the flames from gutting the building, though the Brigade did prevent neighbouring premises being affected.

Sam was last seen on the previous evening by the porter who was locking up the premises; he appeared to be leaving and had disappeared by the time the gaslights had been turned out. However after the fire was extinguished, Sam’s badly burned and scarred body was discovered by two police constables as they searched in the upper storey. His body was in a sitting position against a counter in the making-up room, under a pile of coats. There were extensive cuts on his left arm and wrist, and a small knife discovered by the body, leading to speculation of suicide.

At that time Samuel and his family were living at the Chestnuts on Derby Road, Sandiacre. And at the inquest into his death, held on May 29th, it was revealed that his twenty-year-old son, George Howard, had left his father at the factory, expecting the latter to return home later, by train, as he usually did. Instead Sam appears to have secreted himself inside the building, until it was locked and empty, and then tried to commit suicide. He had been ‘depressed and morbid‘ for several months though no-one had known why; he had been frequently heard to wish he could draw an end to his life. However the doctor who had examined the body pointed out that the cuts on the arm and wrist were superficial, and that the heart and lungs pointed to a death through suffocation.

Thus, the inquest jury found that “death was caused by suffocation, produced by being in the burning building in which the deceased had secreted himself alone: that he had inflicted the wounds upon himself: and that he committed suicide whilst in an unsound state of mind”.

The origin of the fire remained a mystery.

Boilermaker Benjamin junior married in 1865 to Ann Parsons, eldest child of framework knitter Charles and his second wife Mary (nee Campbell). He eventually moved into the clothing and hosiery industry and at the end of the century was trading as a clothier and draper in South Street.

Richard Hithersay (RBH) recalls Benjamin junior as “a very vigorous and outspoken ‘freethinker’’. And indeed he was. In April 1885, approaching the date for the General Election later that year, a meeting took place at Ilkeston Town Hall where the audience was addressed by several Conservative speakers, including the candidate for the Ilkeston Division, William Drury Nathaniel Drury-Lowe. Everything went well and William was cheered and applauded as he spoke. At the end of the candidate’s address, a man in the audience asked permission to submit an amendment to the resolution of confidence in Mr. Drury-Lowe which had been proposed. He was granted that permission and so proposed that “this meeting has no confidence in Conservative gentlemen representing them in Parliament and is determined to use every legal means it has at hand to overthrow the candidature of Mr. Drury-Lowe”.

No prizes for guessing who this audience member was !! The amendment was seconded (by Benjamin Gregory, son of William), voted upon and defeated. Mr. Drury-Lowe’s canditure was then confirmed.

Youngest daughter Jane was the first of the children to be born in Ilkeston, in 1848, and ‘remained at home’. After the death of her father she was still keeping shop at the home which was then 84 Bath Street. And that is where she died in December 1923, aged 75.

Alvah was also a boilermaker and lived with his sister Jane after the death of their parents.

______________________________________________________________________________________

And here is an example of Benjamin’s free-thinking — brief notes on a speech he gave to the Ilkeston Political Debating Society on Wednesday, 5th January 1887, in the Board Room of the Town Hall. It was on the Disestablishment and Disendowment of the English Church.

Benjamin defined first of all the difference between a Free Church and a State Church. The Church of Rome was a great example of a Free church, having full control over its own affairs, and being free from all external interference. He contrasted this with the State-governed English church, with a woman for its head, and its rites and doctrines settled by Parliament. The English church was not a self-governing body, but was simply a servant of the State.

Why should the Church be disestablished ?

First, because it was not the church of the people, the masses of the people being entirely outside it. This great institution had been prostituted to find a home for the younger scions of aristocracy, The only way to sweep away such abuses was to make the church responsible to the people.

Benjamin then went over a considerable amount of historical ground to prove his second reason for disestablishment, viz: that the Church had almost without a break been the creature of Crown and State.

The third reason was that the general action of the Church had been against the will and wishes of the people, and had prevented progress and reform.

The neglect of the education of the people by the Church up to the end of the 17th century was exposed by Benjamin in mercilous language. It was owing to the efforts of the noble Quaker, Lancaster, that at least for very shame the Established Church had to move in this matter and establish the National Schools. Did not they all remember the bitter oppostion of the clergy in their home town to the Education Act of 1870? It was keen and earnest, and there was no mistake about the principles by which the opposition was actuated. To disestablish the Church would remove one of the greatest stumbling-blocks in the way of free and full education.

The way in which the church had hindered reforms was the shown by Benjamin. The Church had been fairly tried and found wanting, had misused her power and her riches; and had used them not for the people but against them. They demanded in the great name of justice and religious equality that she should claim no more power or influence than any other religious body. The Church in future must be sustained and supported by those who desired her existence, and must not infringe on those who do not believe in an ecclesiastical establishment.

Benjamin then passed on to the question of disendowment which was really the crucial question. He pointed out the difference between clerical property and private property, and asserted that the State had set aside revenues raised from taxation to pay certain officials for doing certain work, and if the State wished to alter this arrangement it was perfectly within its rights to assign those revenues to other purposes and uses.

Touching on the powers of Convocation, Benjamin showed that the body was simply a tool of Parliament, and could not act but by the permission of Parliament. That was shown by the fact that if a clergyman obeyed Convocation in opposition to the House of Commons he would speedily be deprived of his living. That showed who was the person’s master — Convocation or Parliament.

Benjamin’s views of the endowments of the Church were explained by a local illustration. The Duke of Rutland’s Cotmanhay tenants had built on the Duke’s land, and had to abide by the consequences. It was the same with those pious ancestors who had left their money to the National Church; that money was invested in something that was not under their own control, and they must abide by the consequences. The law said to the Duke that the cottages built by his tenants were his property; and reason and law said that under the same conditions the property of the Church became national property, and must be used for the national benefit at the discretion of the House of Commons.

Speaking on the question of tithes, Benjamin showed their origin and growth. He strongly denounced the legalised robbery which went on under the name of “extraordinary tithes.” Was there any justice in the Vicars of Ilkeston under the authority of the State mulcting the widows of Dissenters of 10s, not for any duty performed, but simply as a legal right? To rob the people in the name of religion in broad daylight and to take the policeman to make them “stand and deliver” demanded a stronger term than infamous. They must point the finger of scorn at a church which in this 19th century allowed itself to be supported by such iniquitous laws. The only remedy for these things which could satisfy the masses of the people was found in the disestablishment and disendowment of the English State Church

______________________________________________________________________________________

John Allen, railway porter

“A tiny cottage was built at the side of the line leading to Cossall.

This was occupied by John Allen, the sole porter at the Junction. He married Miss Southey.”

John Allen of Desborough, Northamptonshire, was the railway porter who married Frances Ann South of Grantham, Lincolnshire in 1869, shortly after the accident suffered by his colleague, Samuel William Bond, at Ilkeston Junction. (See the Town Station)

______________________________________________________________________________________

The Rope Walk alias the Ropery

At the eastern end of what was to become Station Road, close to the river Erewash border with Nottinghamshire and on the eastern side of the Erewash Canal was a collection of houses known as the Rope Walk (or Ropery or Ropery Walk), accommodating up to a dozen households.

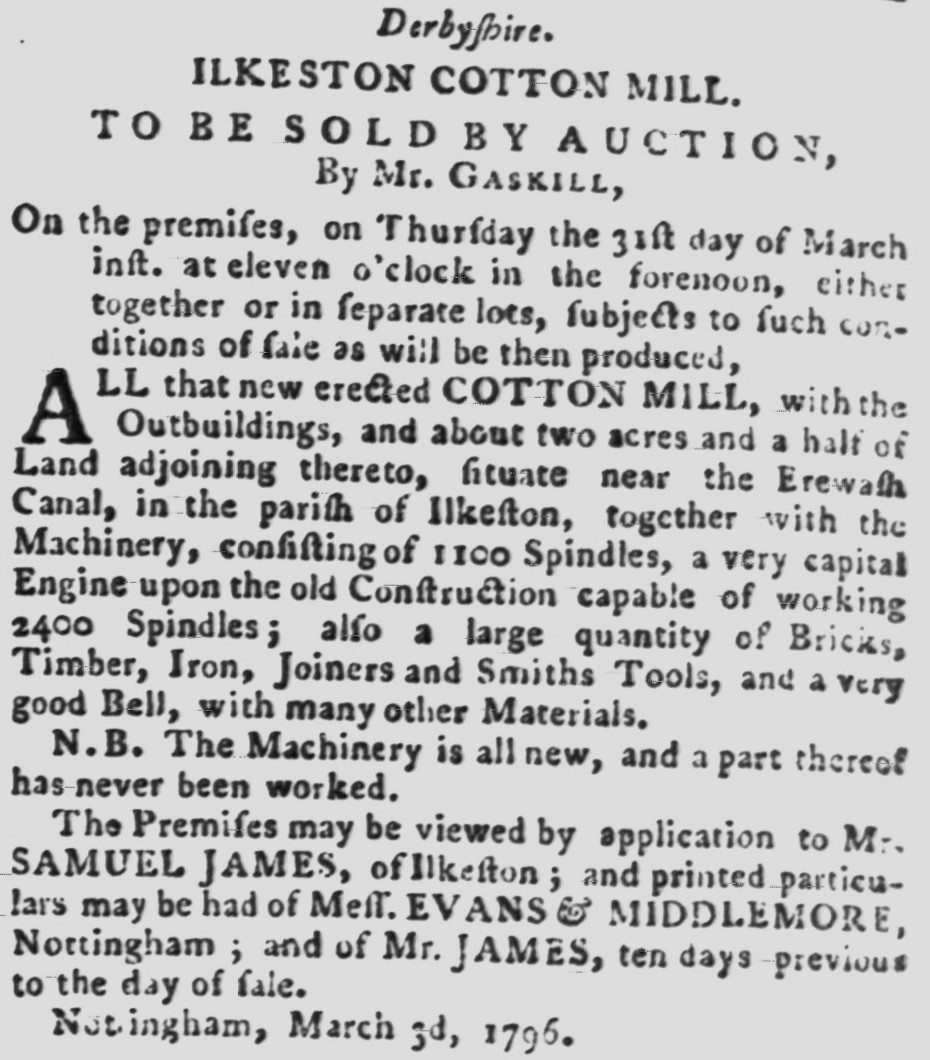

Before New Street/Station Road was extended beyond North Street in the 1860’s and more especially in the 1870’s, the Rope Walk area was pretty inaccessible; its main approach from Ilkeston was along the east side of the Erewash canal, having crossed that canal by the bridge on (what is now) Awsworth Road. And if you had ventured there towards the end of the nineteenth century you would have discovered Ilkeston Cotton Mill, operated by a partnership of Thomas Wyer, Samuel Richards, Samuel James, Thomas Hill and Charles Latham junior. This partnership was dissolved in 1793 though the mill continued to operate.

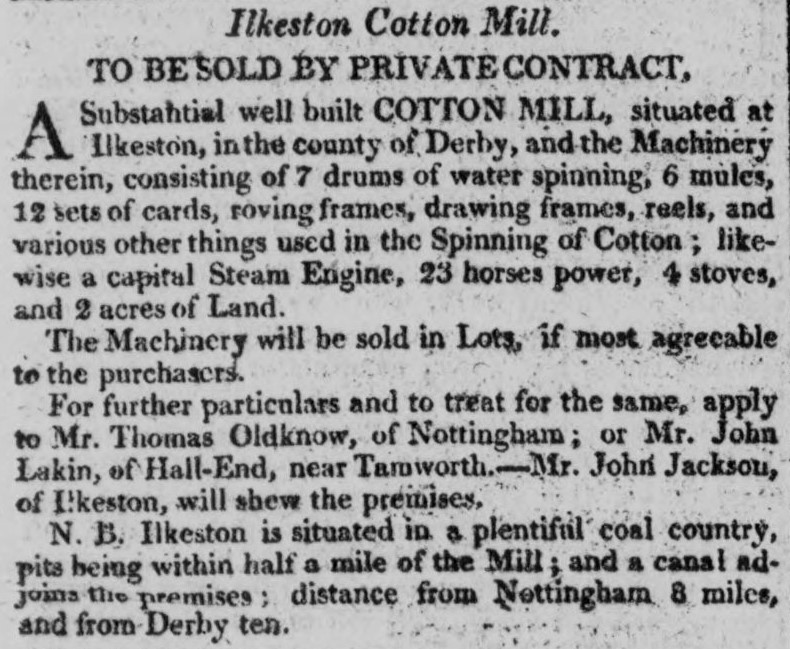

In February 1799 the Mill’s water wheel — six feet wide with a 20 feet diameter — was once more advertised for sale, along with machinery and allied milling apparatus. (Had it failed to sell in 1796 ?) Then, in late 1801, it once more appeared in the Derby Mercury.

The mill premises were bought by John Laykin, Thomas Oldknow and Henry Hollins, but just a short time later , in April 1802, they was up for sale again, a sale which was soon postponed !! At this mtime the mill was being described as ‘with four Houses and about two Acres of Land’, a Steam Engine of twenty three Horses Power, seven drums of Water Spinning, 3 Mules, 132 Spindles each, three ditto of 108 Spindles each, four Drawing Frames’ as well as joinery, blacksmith and sundry equipment. John Jackson was in charge of the premises and was on hand to help prospective buyers. As it turned out, John was the one to buy the property and in 1805-1806 he took over the shares of Laykin, Oldknow and then Hollins, demolished the mill at this time and built a couple of warehouses there, where he could carry out his work as a ropemaker. It was at this time that the ropewalk was set out.

John Jackson continued to work there, at least until the mid-1820’s, although he had sold the business to James Potter at the end of 1817. Eventually the premises were acquired by Richard Evans about 1867.

______________________________________________________________________________________

One of the other Rope Walk families was that of stone miner William Neal, wife Mary (nee Swann) and six children, who had come from Codnor to Ilkeston about 1849.

One day in 1853, William left their three-year old son Walter in the house and returned a short while later to discover him gone. An hour and a half later, a general search discovered the lad drowned in the adjacent canal.

While returning a verdict of ‘accidentally drowned’ members of an inquest jury added a complaint that the occupiers of these houses had no proper road to access their homes and had to use the dangerous tow-path which belonged to the canal company. They hoped that the owners of the houses would provide a suitable road to prevent people using the canal path.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Adlington Mill

In May 1900 the freehold, five-storey Ilkeston (Adlington) Mill, (including a substantial basement), was put up for sale or rent. It had ample steam power and modern machinery in a six-sack roller plant, with its own private railway siding to the mill. The estate also included stabling for eight horses, with a large loft above. On its west was land owned by the Duke of Rutland, on the north by land owned by John Henry Clay, and on the east by land belonging to H.B. Clay and the Duke.

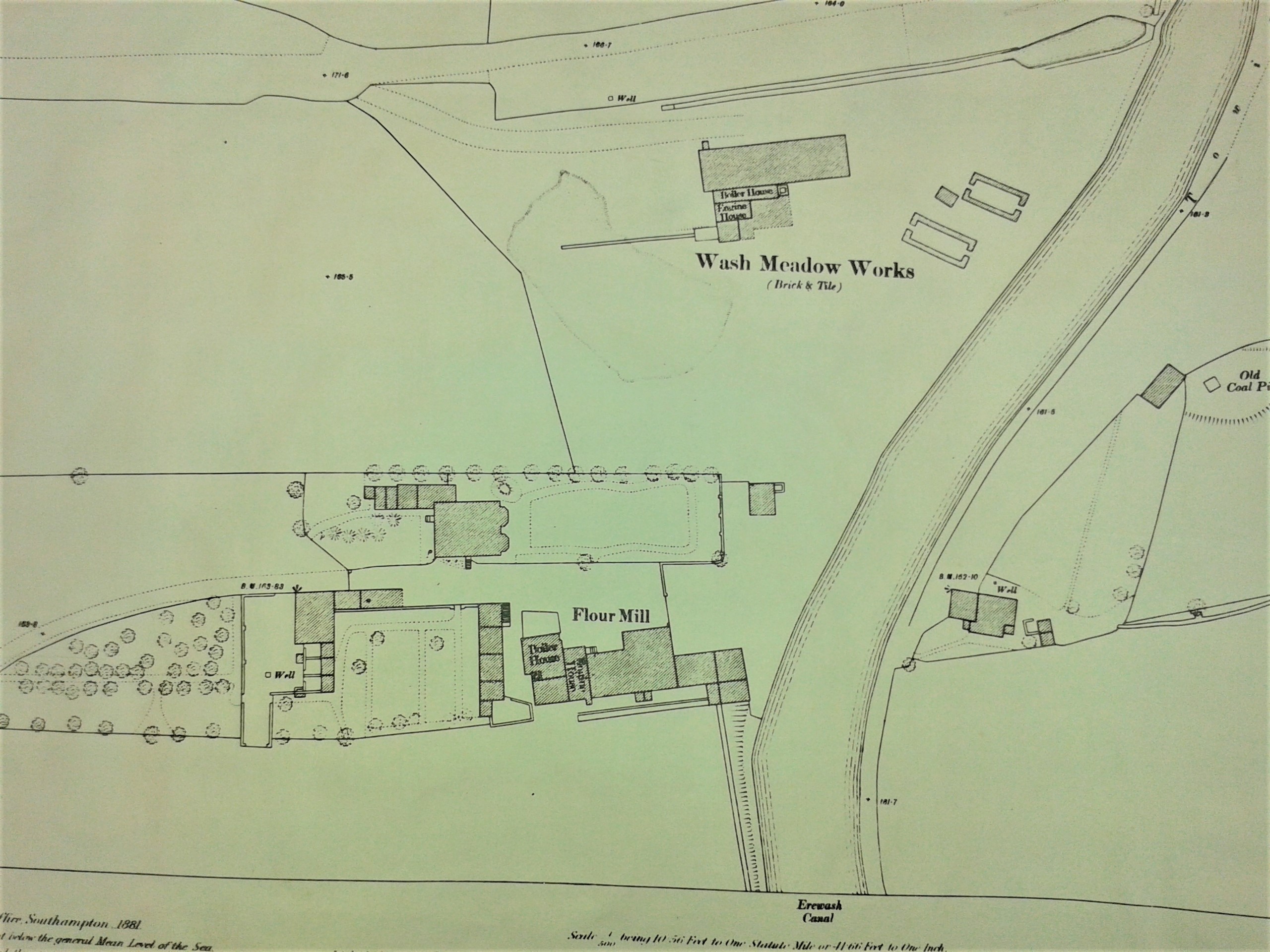

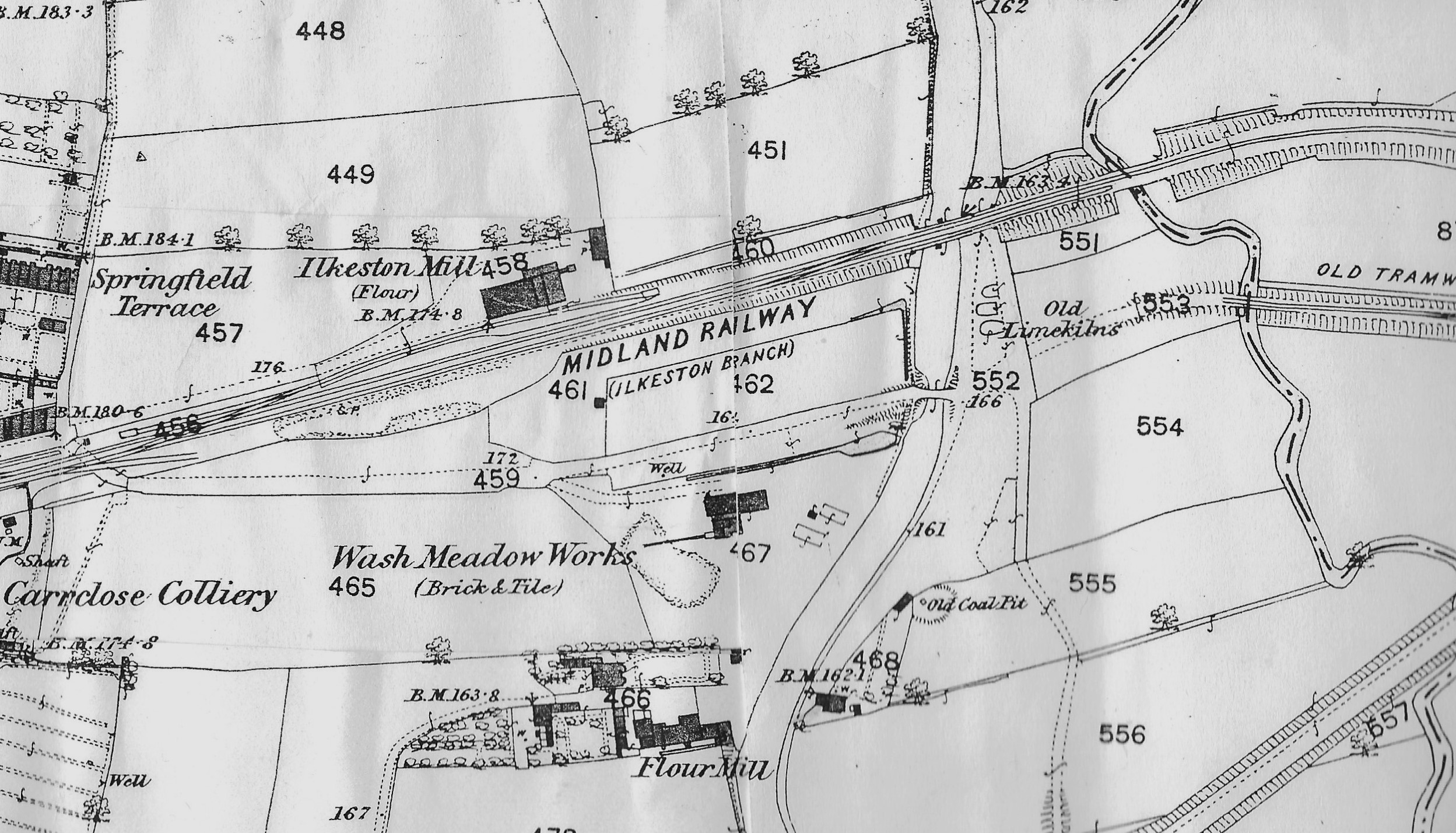

Adlington (Ilkeston) Mill in Wash Meadow, 1881 (labelled 458)

Just after midnight on Saturday, February 17th 1912 a serious fire destroyed Adlington Flour Mills, sited to the east of Springfield Terrace, and north of the Midland Railway branch line from Ilkeston Junction to Ilkeston Town. The mill had been built in 1877 by William Sampson Adlington of Kirk Hallam* (below). As you can see, it was a structure of four stories with a basement, 60 ft. long and 40 ft. wide. Although it contained a lot of valuable equipment, it had not been in regular use for several years. The damage was estimated at £10,000 (today worth over £1m).

Turner Photo, Ilkeston … from a contemporary postcard (Jim Beardsley’s Collection)

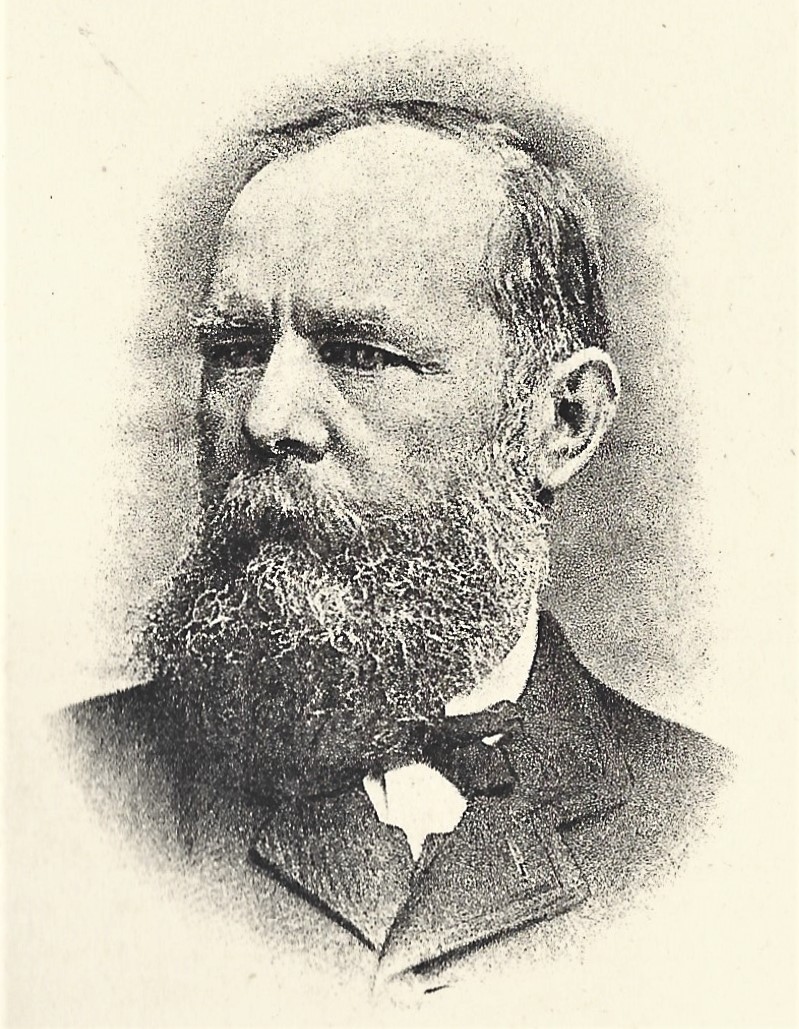

*William Sampson Adlington was born at King’s Mill, Mansfield, on January 10th 1834, the son of miller William and Dorothy (nee Sampson). His birth was listed in the Society of Friends (Quaker) records in 1834, though he was later baptised at St. Mary’s Church, on January 21st 1862. He was educated at Ackworth, a Quaker school in West Yorkshire, and arrived in Ilkeston in 1855, being in business as a miller and corn merchant. He was also a partner in the Manners Colliery Company.

William was voted on to the first School Board in the town, in 1878. And in 1885 he was appointed a justice of the peace for the county of Derby, sitting regularly at Ilkeston Petty Sessions.

On April 10th 1861 he had married Margaret Alice Hirst, daughter of Sheffield druggist George and Margaret Greenwood (nee Dyson).

William died on March 31st 1890 at his home, Kirk Hallam Hall. He was buried in a family vault at Kirk Hallam Church, next to the Hall, on April 4th.

William’s wife/widow, one son and four daughters survived him and on the 1891 census they can be found at Netherlea House, in Lawn Avenue. This property had just been vacated by solicitor John Bamford Slack who, in 1890, left Ilkeston for a ‘promotion’ in London. His place in the firm of Thurman & Slack was taken by Frederic Cattle so that it became Thurman and Cattle (and later Thurman, Cattle & Nelson).

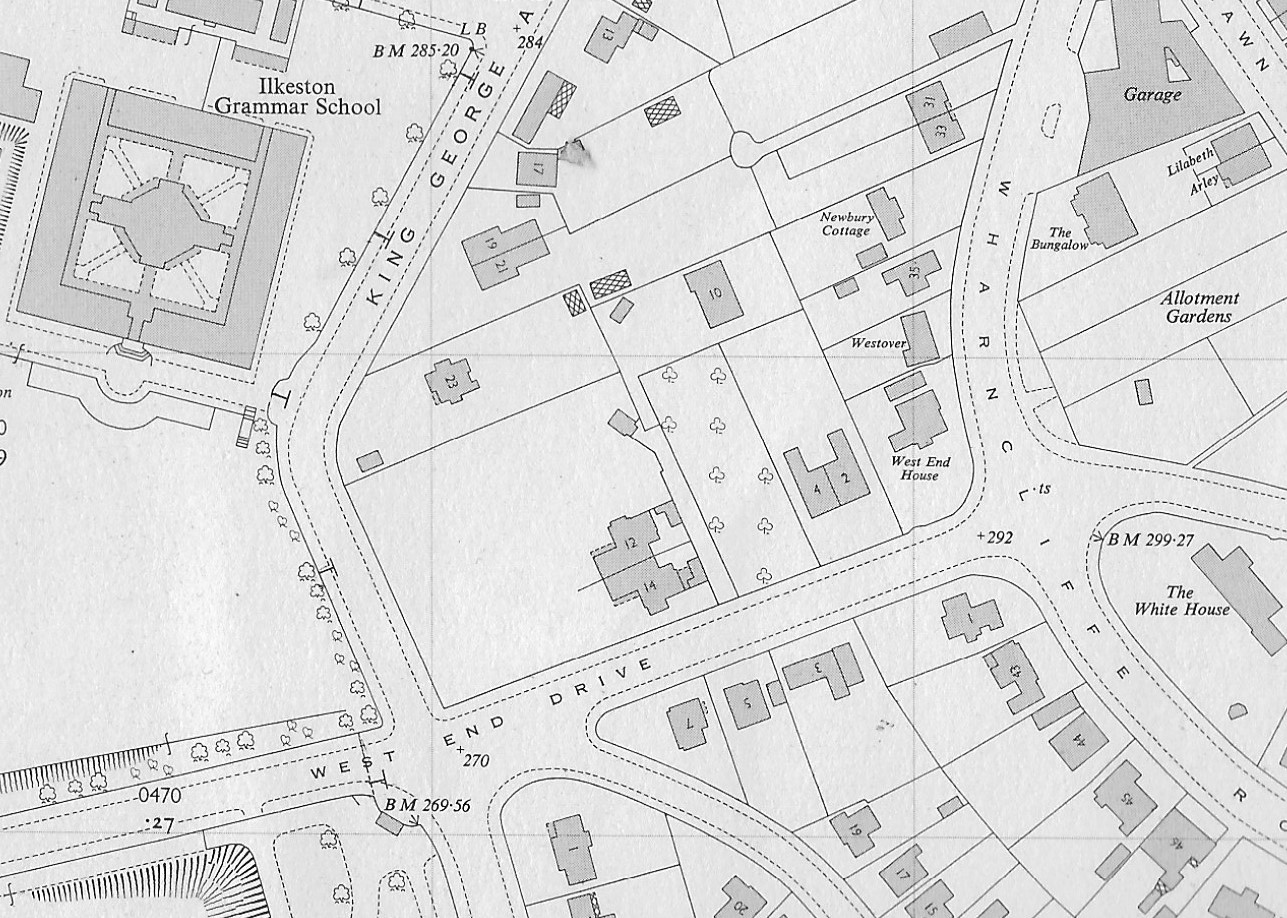

In June 1893 Netherlea was put up for sale. It was described as a charming semi-detached residence, with tennis court and garden, and splendid views over West Hallam, Mapperley and Shipley. It had an entrance hall, dining room, drawing room, kitchen, scullery, larder and cellars, four bedrooms, bathroom and a large (full-size) billiard room. Ready to be occupied by June 24th. Netherlea and its neighbour were situated at what is now the junction (north-east corner) of King George Avenue and West End Drive. (see map below)

This map, c 1960, shows the semi-detached houses numbered 12 (Inglewood) and 14 (Netherlea) to the immediate north of West End Drive. The houses have since been replaced by a new and small housing development in a cul-de-sac off West End Drive. Inglewood was originally built for the Woolliscroft family.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Just off the Rope Walk was Spring Grove Terrace, later known as Grove Terrace