We start our walk on the east side of Bath Street, just north of what is now the junction of Manners Road and Bath Street, facing south and looking towards the out-of-sight Market Place, seeing the tower of St. Mary’s church in the centre distance.

In the 1850’s, on our right we would see Ilkeston’s Bath Houses but on our side of the road we stand next to one of the town’s two railway stations. The gas lamp you see on the wall marks the entrance to the station. A little further up on the left is Brussels Terrace. These features you will see on the sketch map below.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

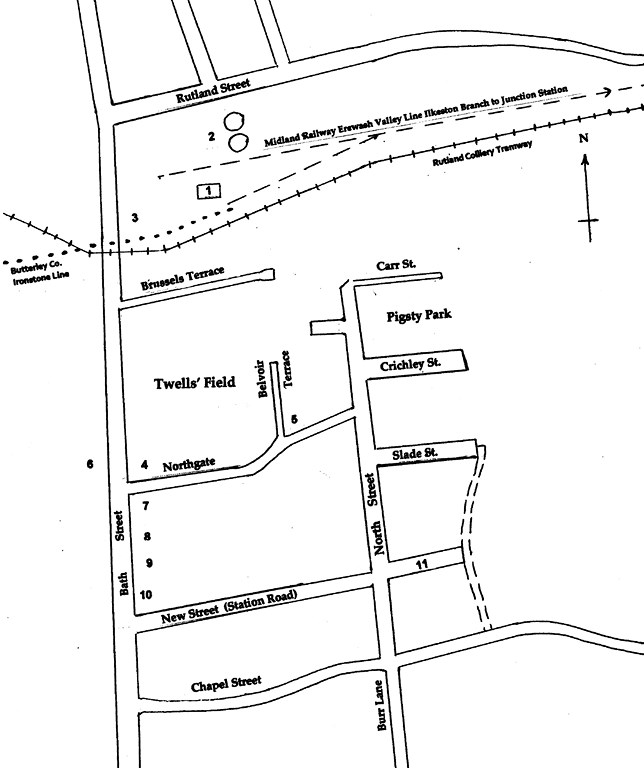

A simplified map of the east side of lower Bath Street about 1866.

- The Town Station

- The Gas Works

- James Chadwick and family

- William Riley, the unfortunate butcher

- John Trueman and the Durham Ox

- The Poplar Inn

- The candle maker: Moses Mason and family

- The Brunswick Hotel

- The Woolliscrofts

- The land of Joseph Fletcher

- Great East Street

If you look on the 1841 Census for Ilkeston you will find no railway station house … it wasn’t built then. However in a letter to the Ilkeston Pioneer of Aug. 4th 1893, ‘a Pittite’ writes …

(Richard Straw) lived in a small house where the Midland Town Station is, and worked the engine belonging to the pit that was nearly opposite the Rutland Hotel.

You will certainly find engineer Richard Straw and his family.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

The 1840s

The Midland Railway develops 1836-1847

In November 1836 the Midlands County Railway set out its plans to extend its network. This included plans for a branch line from Bath Street to Ilkeston Junction.

Derby Mercury (November 9th, 1836)

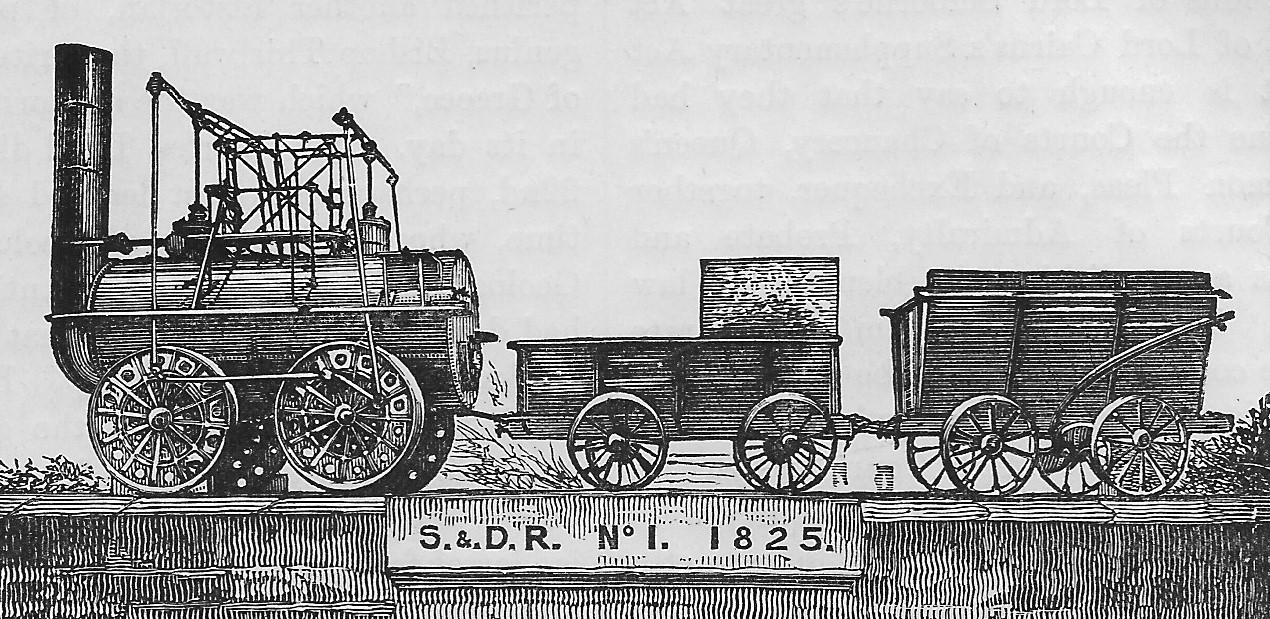

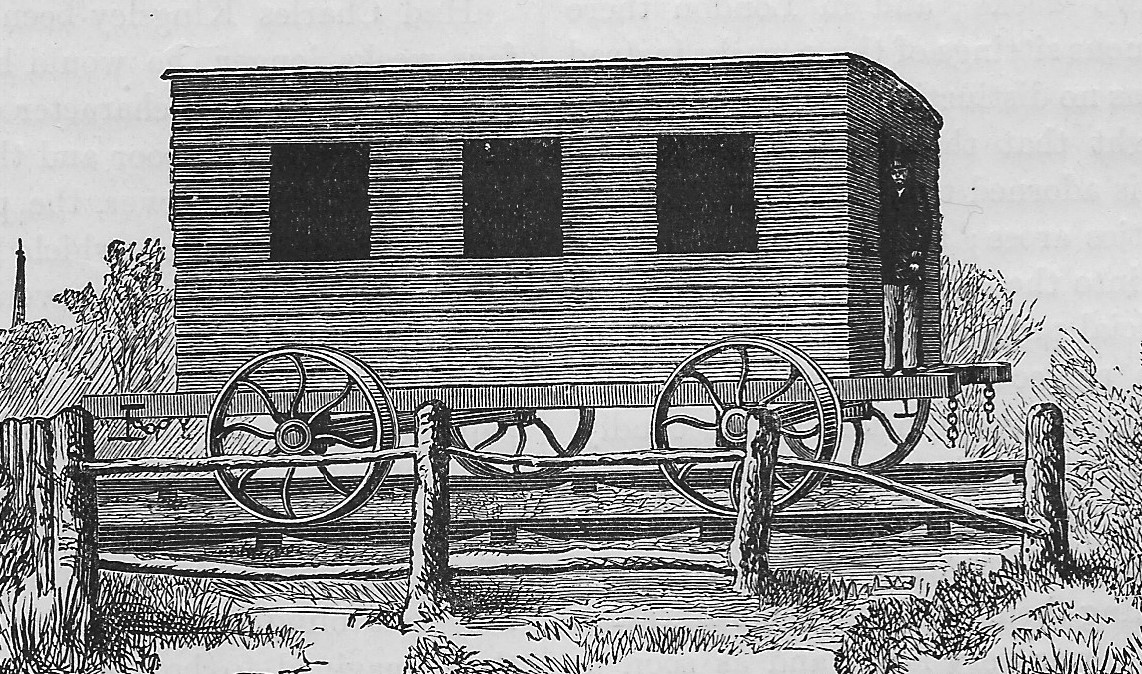

Stephenson’s ‘Locomotion’ on the Stockton & Darlington Railway, 1825, and (right) the first passenger carriage ‘The Experiment’ to carry dignataries on its first journey.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

The 1830’s had brought the railways, their growth encouraged and stimulated by coal proprietors who saw the potential of this new method of transport in getting their product to markets more quickly and cheaply than either by road or canal. Thus, the building of the Erewash Valley (Midland Railway) main line was undertaken because the valley lay above one of the richest coalfields in the North Midland area.

Adeline remembers that “the Midland Railway branch line, with its small station house was down a long slope”. This ‘small station house’ was called the Town Station — though perhaps ‘platform shed’ might be a more apt description — and was at the end of a branch line joining it to Ilkeston Junction Station (at the bottom of what is now Station Road).

May 30th, 1839…..the Nottingham-Long Eaton-Derby section of the Midlands Counties Railway was opened.

May 4th, 1840……the Midland Counties extension line from Long Eaton to Leicester was opened.

June 30th, 1840….the Leicester to Rugby section was opened.

May 1844.……… the Midland Counties Railway was joined with the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway and the North Midland Railway to create the Midland Railway.

June 1845 ….. several townsfolk gave evidence to the Parliamentary Select Committee exploring the promotion of the Erewash Valley line. The Erewash Canal Company put forward its view that the water communication of the district was amply sufficient to accommodate the existing traffic, but many local coalowners expressed the view that they would much prefer to use the railway, if there was one. This view was one echoed by the Duke of Rutland. Farmers too, like Thomas Potter, and miller Matthew Hobson, would much prefer to use the railway, as did Ilkeston indutrialists like the Carrier and Ball families.

July 26th, 1845 …. “Great excitement prevailed in Ilkeston on Saturday (July 26th) in consequence of the passing through committee of the Erewash Valley Railway Bill“ (Nottingham Review, August 1st, 1845)

September 6th, 1847…the Midland Railway fully opened its Erewash Valley line linking Nottingham with Codnor Park for a distance of nearly 19 miles. The occasion was marked by a dinner given by the contractor, Mr. Leather, at the Rutland Arms Hotel, across the road from the Town Station, and in the evening there was music and dancing, a small exhibition of fireworks, and musical hand-bells. Mr Whitmore, the first station-master, and his assistants were on the look-out for any trouble-makers !! The first six-mile stretch of this line, from Nottingham to Long Eaton, was along the Nottingham-Derby line. Then the line ran from Long Eaton, via Sandiacre, Ilkeston and Langley Mill to Codnor Park, with stations at all these places. On this date the first train to travel the new line left Codnor at 7.45am and arrived an hour later at Long Eaton, its engine ornamented with flags and evergreen. Later there were three trains daily travelling each way along this route.

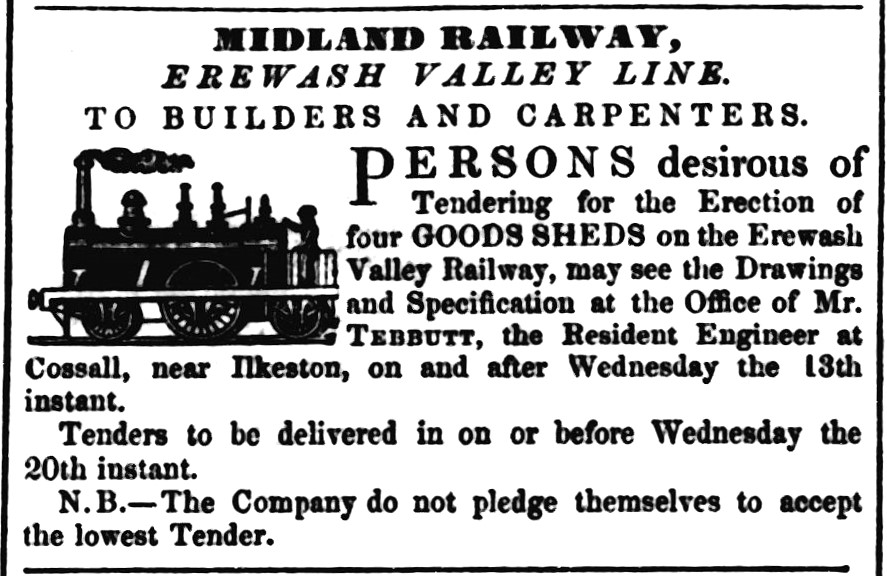

from the Nottingham Mercury and General Advertiser (October th, 1847)

John Cartwright recalls that while this line was being a built a confident railway navvy “paid a visit to Jerry Wigley’s Inn (the Market Inn) where he boasted that he could thrash any man in the town. A lace hand, Jack Pepper by name, if I mistake not, accepted the challenge and I witnessed the fight, which I must say I enjoyed, as I did some others in Woodroffe’s close (behind the King’s Head Inn), and in the fields leading to the hilly-holey pasture. “Well the navvy got ‘pepper’ with a vengeance, but not until there had been a very hard struggle. “Ilkeston was proud of Pepper that night, for the Ilkestonian was a quiet fellow enough as a rule. “There was only one constable in those days and he was ‘Small’”

In fact Jack Pepper, who lived only a few doors from the Market Inn, was born in Nottingham. The ‘Small’ constable was a reference to George Small, Ilkeston’s Parish Constable since 1830.

January 1848 … by courtesy of the Ilkeston Gas Company, the Town railway station and entrance were now lit by gaslight.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Ilkeston’s two stations

As the Erewash Valley line began its ‘historic journey’ there were local rumours that the station at the Town teminus wouldn’t cater for passengers but for goods traffic only; passsengers would be accomodated at the Cossall Station in Cossall Meadows at ‘Ilkeston Junction’ — there being more population there than at the Ilkeston side of the line !!! Hurriedly a deputation was organised to canvass that the Railway’s committee give thought to changing this policy — what was the usefulness of the branch line to the Town Station at the bottom of Bath Street if it didn’t cater for passengers ? The Committee was symapthetic to these solicitations and agreed to operate the branch with a horse-drawn carriage until something could be agreed with the ironstone and coal works on the other side (west side) of Bath Street. And, sure enough, the terminus was soon catering for passengers and goods.

The first Town Station master was Thomas Whitmore, ‘an amiable and cultured man’ (according to ‘Bath Street‘) He had previously served as schoolmaster at the Louth Union Workhouse in Lincolnshire where his wife Ellen (nee Shields) served as schoolmistress and where their son Thomas William was born. On the 1851 census Thomas was still station master at the Ilkeston town station house, with his family, but ten years later he appears as a brewer’s clerk in Burton on Trent.

It was a long slog from this station up to the top of the town as Venerable Whitehead recognised in 1854. “I would gladly avail myself (as I see others who would) of some cab or omnibus to mount that hill – not a vehicle of the sort at hand! Come, come, Ilkestonians, this is not worthy of the spirit I trace among you. The railway, with all its defects, has had the kindness to hold out an arm to you as far as the elbow joint. Do you meet it with some conveyance to the market-place”. It is still a long slog!! And there are still calls for a bus to travel to the Market Place!!

The main station at Ilkeston Junction was very small and primitive. From this Junction station ran the short branch line to the Town Station, a line opened for goods and passengers at the same time as the main Erewash Valley line and which had a natural upward slope.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

A Sunday School outing: 1849

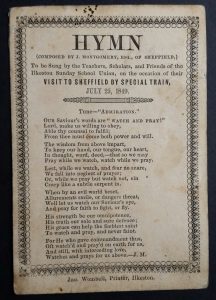

In July 1849 — just a couple of years after the opening of the Erewash Valley line, a ‘few’ children, accompanied by guardian adults travelled along it. The event was recorded by the Nottingham Review….

The children connected with the Methodist New Connexion, Independent, General Baptist, and Primitive Methodist denominations, at Ilkeston, Stapleford, and Kimberley, and the surrounding neighbourhoods, to the number of 3000 and upwards, with their teachers, went by train on Wednesday last, on an excursion to Sheffield. As early as six o’clock in the morning, the railway stations began to be thronged, and, in about an hour, the two trains, consisting of about 70 carriages, (including ‘tubs’, as the covered carriages provided would not contain the vast multitude,) were on their way to the ‘smokey town’, where the party arrived soon after ten o’clock. In order to distinguish the little bands, each child wore a ribbon … and, as the whole paraded the streets, the scene was enlivened by many of the children carrying small flags made for the occasion. Visits were paid to the Botanical Gardens, Cemetery, and other places of resort, and refreshments were provided in the school rooms of the different denominations …. The railway directors on this occasion … reduced the fares to the low rates of sixpence for each child to Sheffield and return, and one shilling and threepence each for their teachers...These two items (above and below) are from the Andrew Knighton collection. Andrew adds .. the journey must have been very uncomfortable in the 3rd class open carriages with wooden benches (the tubs) in which they probably made the trip, but I suppose this wouldn’t have been noticed in all the excitement. As they were about to set out, the children would probably have gathered at the Junction station, not the Town station, … and one can imagine the scene as the excited Ilkeston flock assembled on the platforms.

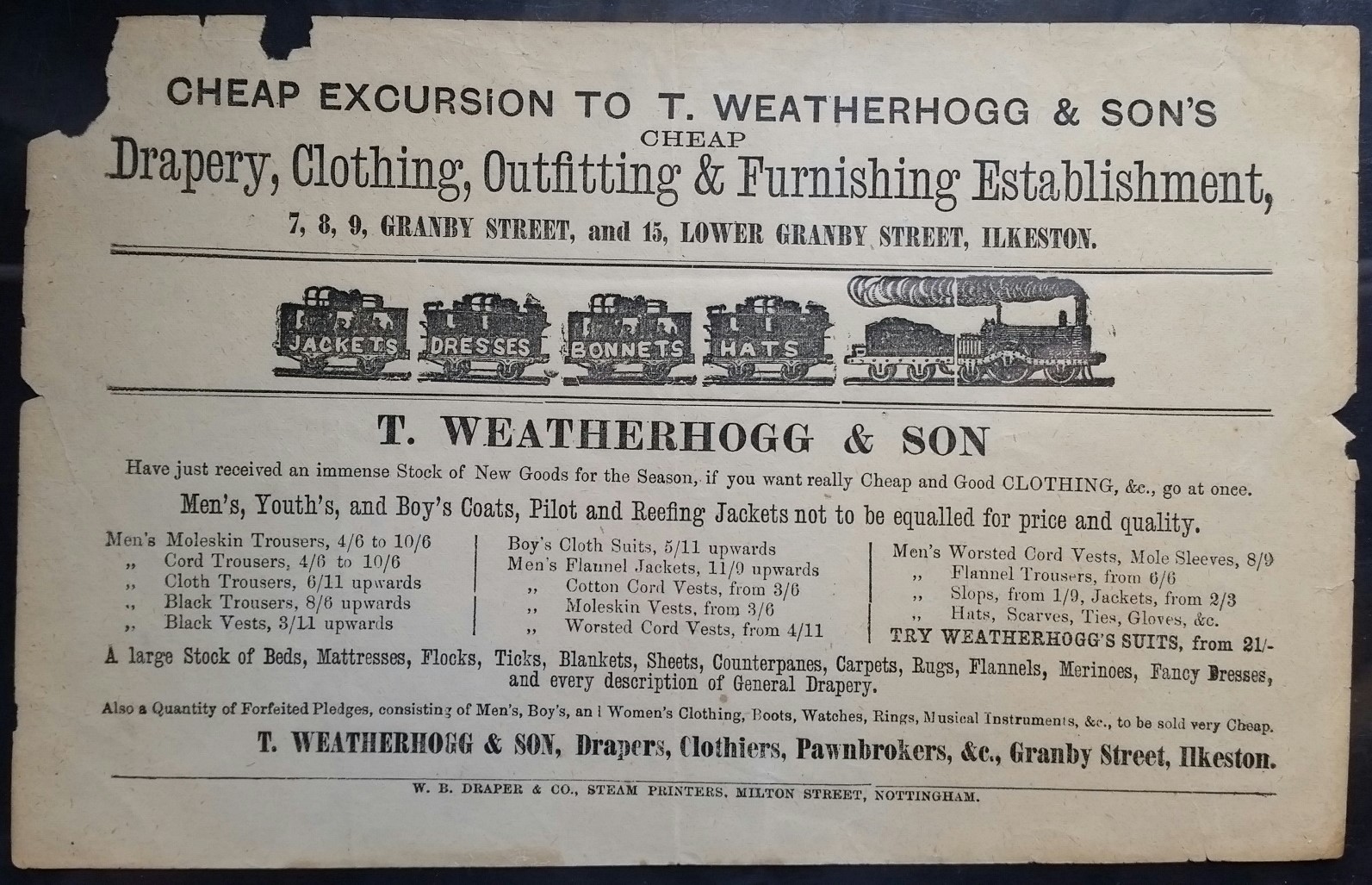

‘an image of a local flyer that shows the type of train that might have been used on the day’ adds Andrew.

(Thomas Weatherhogg arrived in Ilkeston with his family about 1868

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

The 1850s

Travelling between the stations: 1850s

Prospective railway passengers who wished to travel out of Ilkeston were faced with an unenviable choice – either make a perilous journey on foot directly to the Junction Station or assemble at the branch Town Station and allow the Railway Company to take them to the other station. Opting for the latter was not without its dangers !!

“A strange second-hand locomotive used to ply on this unwelcome ‘branch’ but it broke down, and since then, horse-flesh has done its best to rival the ancient speed”. (IN November 1855) The Nottinghamshire Guardian reported that three locomotives were broken in a very short time on the branch line, on account of its steepness, and were thus replaced by two horses. Once started from the Town Station, the passenger carriages rolled down to the Junction in less than two minutes; it took ten minutes to accomplish the return journey.

Sheddie Kyme described this carriage journey…. “The old town station will be recalled by many. This was situated where the platform of the present town station is. …. From this station passengers were conveyed to the junction by a rather quaint method. There were generally two carriages which were devoid of the least particle of upholstery, and when the passengers had taken their seats, two horses were connected by a chain arrangement. These horses would start the carriages on their downward journey to the junction station, and were then freed, the carriages relying upon the slight fall in the construction of the line to complete the journey. …. Shortly after the new road (now Station Road) to the junction station was completed, the old town station was abandoned, and the line for passenger traffic was not opened until opposition was threatened by the construction of the Great Northern line”.

It was this journey on the branch line which the Ilkeston News (November 1855) found it could recommend as … “a sedative to all irritable and choleric persons – however much disposed we were to be angry and fly into a violent perspiration at the bottom (the Junction), we often became quite cool and philosophical before we arrived at the top (the Town terminus). We would dedicate this branch line to Patience and Perseverance, those choice twin sisters, without whose faithful help the tedious road would lie in sad and dreary length – a terror to the poor traveller with his parcels and cases, and a literally unexplored desert to the genteeler visitor, thus frighted to consider us out of the world, far away from the civilised haunts of man”.

Adeline also describes the journey……. “For a few years passengers for Nottingham were taken down to the Junction (from the Town Station) in two (railway) coaches which were open from end to end, and started on their way by horses. But either the Company turned economical or found the traffic not sufficient to warrant taking the travellers down to the main line, so discontinued the horse accommodation, and people were obliged to walk down to the Junction. This was great hardship for those who travelled regularly by the Midland Railway. There were no buses, so all had to walk and when the weather was bad the so-called waiting room (at the Junction Station) was a cold and dreary place in which to wait. The Midland Railway was not what it ought to have been.“

Rather than wait for the carriages to take them to the junction, pedestrians could go via the Slack Lane route — along what was later Rutland Street and then following various old tramways, crossing the Erewash Canal on the journey.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

In April 1854 James Weston, a porter in the employ of the Midland Railway Company, was found guilty of being drunk in charge of a carriage from the Town Station to the junction. He was fined 10s with 15s 6d expenses.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Railway complaints: 1850s

Adeline was not the only one to complain about the railway company or its stations. In 1854 the Pioneer compiled a list of grievances from its readers…. late passenger train arrivals; parcel trains that delivered goods from Derby in two, three, four and even five days, while goods from London came quicker by canal than rail; parcels from London to Ilkeston often went via Nottingham and so incurred an extra cost; a waiting room at the Town station that could accommodate only seven persons in a town of 7000 and that was often used to store parcels and luggage; a filthy and muddy entrance to the station.

And at this time the Ilkeston News was always happy to add to the criticisms of the railway company. In 1855 it published this letter from ‘Viator’ on ‘The Ornamenting of Bath Street’ …… “On looking over the vast improvements which are taking place in this town from the Church to the channel, every one must say it is ‘very good’, especially down Bath-street, with its bold and beautiful sweep of hill, which, whether seen from the top or the Baths (at the bottom) is perhaps one of the finest situations in England for street effect; and certainly some of the owners have done credit to it. “Others have tried all they could to disfigure it, especially the owners of all those old rusty sleepers, placed end upwards, at the entrance of the magnificent Station belonging to the Midland Railway Company. Really the design of that Company is a striking proof of their taste in street ornament, and, as such, merits the thanks of all who think they deserve it”.

“The ground at the entrance of the (Town) Station gates may perhaps be intended to rival newly-ploughed land on which the rain has mercilessly pelted for several days but as we do not see that any utility is served by it in its present condition, we may justly object to this common mode of imitating the ‘diggings’, both because no gold can be found and because we think that clean boots are some test of our decency amongst our Derby and Nottingham friends”. (IN November 1855)

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Level crossing danger: 1850s

On the western side of Bath Street across from the Town Station, toiled the Rutland collieries and ironstone quarries. A wagon-way incline ran from them and crossed over Bath Street going to the Erewash Canal and Ilkeston Junction, thus facilitating coal to be transported from its origin and on to its markets. The first task of prospective rail travellers therefore, was to negotiate safely two dangerous tramways at the entrance gates to the Town station. (At this time ironstone pits were not subject to the same Act of Parliament as coal pits. No notice had to be given to Government Inspectors when a death occurred. The works were consequently often very unsafe and the pit mouth unguarded. In addition the pits were exempt from local rates).

Sheddie Kyme also gives detail of this wagon-way. “A level crossing ran down by the town station utilised for the conveyance of coal and ironstone from the Pewit and Old Boswell mines (the latter being situated in close proximity to the Manners Colliery) to the Canal Wharf, where it was loaded in boats and taken away. “The trucks came down the incline which ran along the side of the Manor House, then the residence of Mr. John Taylor, near which was an old beam engine, used for the purpose of winding the trucks laden with coal from the Boswell Colliery. “Near the Bath House was a wharf where coal hauliers loaded their carts, after which they would be taken on the weighing machine, attended by Mr. Steer”

These works’ lines were “without any guard to protect the public from the imminent danger’ (of crossing coal wagons). Also ‘teams of ironstone wagons are passing all day long over the rails to the loading dock, and in close contact with these complications of traffic are those which arise from the carting at the coal wharf, weighing machine, and saw mill just opposite.. “A more perilous entrance than that to this station we never beheld – it might most appropriately be designated ‘Death’s Crossing’, or the ‘Gates of Death’”.(IP 1857)

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Good news and bad news: 1857-58

The Pioneer of May 1857… Do you want the Good News first? …

The railway’s Directors have made Ilkeston Junction Station a booking-station for the convenience of passengers arriving too late at the Town Station, and for those coming from the Nottingham side of the line, or residing near the Junction.

But the Bad News is ….. “The (Town) Station-House is about the smallest and most inconvenient ‘hut’ on the line; built on the most approved principles for the exclusion of pure air and the bright sun, and adapted only for a solitary bachelor; if a married station-master, he ought to be able to board at the Rutland Arms, and sleep out, for there is no suitable accommodation for any man who has not given himself up to celibacy. “The Booking-Office well corresponds with the house; it really is not large enough for the purposes of the company’s servants. If a passenger should perchance find standing-room, the probability is that he will also find the hook of Salter’s Spring Balance inserted in his broad cloth or silk umbrella; or if a lady, when in obedience to the cry of ‘Giant Joe’, she attempts to ‘take her seat’, her progress to the carriage will suddenly be arrested by finding that the waggish young clerk has been taking the pattern of her dress or scarf in the copying press, instead of that of a letter. “Seven or eight square feet is all the Midland Railway company afford a town of 7000 inhabitants for a booking office, a parcels’ office and a waiting room….. The two small seats in the office are filled up with parcels, a copying press, files, lamps, brushes, …. and outside, exposed to all weathers, will be seen numerous packages, and the passengers, who there have enough to do to mind the safety of their persons, for the insufficiency of accommodation for mineral and goods traffic renders constant shunting necessary, which is performed by horses remarkably expert in jumping on the platform for their own safety, but to the terror of numerous bystanders”.

In 1857 the Town Station master was Essex-born James Tizley who had previously been a station clerk in Nottingham. In June of that year he was appointed relieving officer for the first district of the Basford Board of Guardians and thus left Ilkeston. “We are glad to hear that a number of our townsmen intend to present Mr. Tizley with a testimonial in appreciation of the kind and obliging manner in which he has discharged the duties of his office towards the public during the period he has been resident amongst us”. (IP June 1857) In 1847 James had married Mary Ann Whitehead, daughter of Trowell woodman Thomas and Alice (nee Philips). In the 1860’s he moved to London and by 1871 was employed as relieving officer in Marylebone where he died of bronchitis in March 1873.

On a dark Monday evening in January 1858 John Hutchinson, unmarried son of cowkeeper Joseph and Catherine (nee Beardsley) of Heanor Road, stepped out of the last, third-class carriage of the Nottingham train at Ilkeston Junction station. At that point the platform was at its narrowest, being about three feet wide, and was situated between the main line and the branch line going to the Town Station at the bottom of Bath Street. John missed his footing, slipped and fell onto the branch line, precisely at the moment that the passenger carriage was coming along the same line from the Town Station. The carriage was pushing five empty trucks in front of it and the first of these went over John’s body, killing him instantly. At the inquest into John’s death, Joseph Tarlton, breaksman of Chapel Street, stated that is was usual to clear the Town Station of empty trucks at night which is what he was doing. There were three standing lights on the Junction platform but the one where the accident took place was obscured by the carriages as they came down the line. Consequently it would be pitch black at that end of the platform. The Pioneer again took this opportunity to criticise the Midland Railway Company for its ‘gross inattention’, and to call for better lighting, a wider platform and improved accommodation at both stations.

At the end of that same year Ilkeston coalminer Paul Bostock was due to appear at Smalley Petty Sessions charged with travelling on the Midland Railway from Nottingham to Ilkeston without a ticket and with refusing to pay the usual fare. Unfortunately Paul could not make it to the court … he was ‘ill’ but he sent his daughter (Ellen?) instead to plead for him. The magistrates were having none of this however and absent Paul got a hefty fine with costs, or if he didn’t pay this time, two months in jail with hard labour!! Not an unusual case you might think … except that this was a rare occasion when coalminer Paul, who was no stranger to the Petty Sessions, did not appear there charged with drunk and riotous behaviour!!

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

The 1860s

More complaints :1860-66

In 1860 the railway company’s newspaper nemesis was scathing of the new first class carriage now running on the branch line. Apparently a cushion had been placed on one side of the second class carriage to transform it into a first class area!

And of course the paper didn’t miss the opportunity to continue the criticism. The approach to the Town station “is scarcely accessible, being carefully barricaded by horses, carts, coal and stone wagons, gates, rails, stables, and manure heaps. A step at the gate of the footway has been so judiciously placed as to draw blood from … passengers. “If you can safely pass these barriers, you will find the perils of travelling to increase as you advance. The getting of a ticket is quite a scene, which reminds one of the scamper and scurry at the London Post-office every morning. The tickets are issued in a cabin so circumscribed as to defy the entrance of the most moderate sized crinoline of the fair belles of Ilkeston. A bench was once seen in the cabin, on which an invalid or tired passenger might await the time of arrival or departure of the train; but this for some time past has been denied the public. Like beggars at a turnstile, no sooner have you turned in for a ticket, than you must turn out to encounter all weathers, and the concentrated stink of filth, manure, privies, cesspools, and gas”. When the time arrives to take your seat, “lucky is he who can find one to take, unless it be on the roof, the steps, a box of red herrings, a bag of mussels, or a basket of stinking fish”. The jolting journey to the Junction passes and once there you find “no waiting room, either for ladies or gentlemen, no urinals or water closets”. Then the connecting train arrives and as the platform is too short “the company have not the means to procure ladders to aid the ingress of passengers to the carriages” so that passengers have to jump off the platform and run into ditches, amongst the points, onto grass and up mounds of gravel to reach many of the carriages. “Both sexes of mankind may be seen pulling and pushing, lifting and squeezing each other into the black and greasy vehicles which travel on this line”.

At the Town Station the station master and his family were accommodated in one living room and a bedroom. Attached to their dwelling were a family cesspool and privy as well as urinals and privy for the passengers. “The stink arising therefrom is most offensive and abominable, and how the station-master and family do live in the reek of such nuisances is a wonder to many”. At this time the suffering family consisted of station master Job Starbuck, son of James and Sarah (nee Simpson); wife Fanny (nee Thorley), daughter of Mapperley journeyman shoemaker Emanuel and Frances (nee Walker); Fanny’s illegitimate daughter Sarah; and the couple’s two children Thomas and Ann.

In September 1862 Cotmanhay boatwright Daniel Longdon left the train at Ilkeston Junction Station having travelled from Stanton Gate but instantly found himself in deep trouble with George Frederick Mills, Superintendent of the Midland Railway Company. The reason for this was the unconventional way by which Daniel had made his journey. He was prosecuted for travelling the whole journey on the buffers of the break railway carriage !! The case was taken to Petty Sessions where Mr Mills stated that Daniel had boarded the train at Stanton Gate whilst it was in motion, thus infringing one of the Company‘s bye-laws. This was an extremely dangerous practice and had led to the deaths of several railway employees whilst trying to assist people into moving trains. The Company therefore asked for strict enforcement of the law. Daniel pleaded his defence; he had booked his journey to Ilkeston on this last train of the night but in error had got out at Stanton Gate. Realising his mistake but anxious to get home and seeing the train departing the station, Daniel improvised and hence his illegal return to Ilkeston. He was fined 20s with 10s 6d costs.

In 1865 a disgruntled passenger signing himself ’X.N.R’, had his letter published in the Pioneer and in which he described the “wretched little hovel called Ilkeston (Junction) station” in detail. It consisted of “one room only, 15ft. by 10, and the space was apportioned as follows: – ‘One portion is used as a telegraph office, another for booking-office, another for goods booking department, and another as an office for left luggage, leaving the grand extent of 7 feet by 5, as ladies’ and gentlemen’s 1st, 2nd and 3rd class waiting-room, for the 2,300 passengers who weekly leave this station. There are no water closets, or conveniences of any kind; but there is a little furniture in the room, which deserves mention – three desks and two stools for the clerks, an iron fender and poker, a clock, various notice boards, and a fixed bench 7 feet long. I forgot almost to mention that on the mantelpiece lies part of a Testament, – most likely a gift from some member of the Bible Society (who has had to suffer here) to the directors, to teach them (should any of them chance to come into the room, and look at it) to do unto others as they would be done by”. This remarkably well-informed observer, who seemed to be passing through the town, ended by encouraging Ilkestonians to petition their Members of Parliament to demand Government inspection of all stations.

In January 1866 railway labourer William Paling was instructed by the pointsman on the branch line to wait for a certain passenger train to pass along the main line before taking a number of trucks up from the Town Station to the Junction Station. However, calculating that he could get the wagons up to the Junction and out of the way before the arrival of the main-line train, William ignored the orders and …. you’ve guessed it !

The collision resulted in several overturned and damaged trucks and numerous shocked passengers.

It also resulted in William paying a 40s fine at Nottingham Shire Hall, guilty of endangering the lives of passengers.

The fine would have been greater had not William’s employer, Mr. Meakin, given him an excellent character reference.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

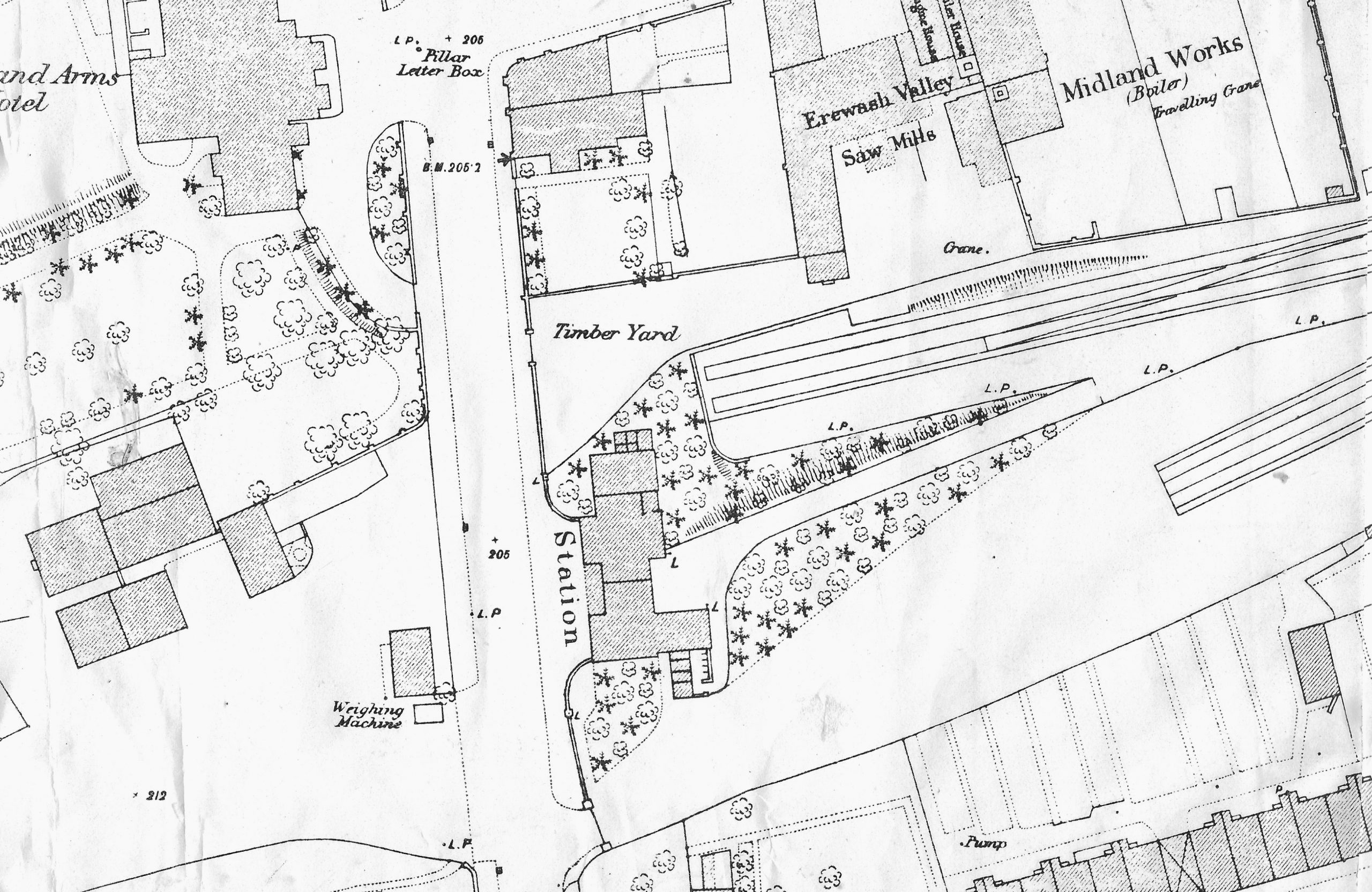

Here is the Town Railway Station ‘complex’ adapted from the Local Board Map of 1866. We are looking up Bath Street towards the Market Place, so that ‘South’ is at the top of the map.

Off the left side (east) of Bath Street you can see, named, Rutland Street at the bottom and Brussels Terrace towards the top.

The railway station is also named (though not too clearly). At A is the single platform for passengers, while on the other side of the station building, at B, is the goods wharf. You can see separate railway lines serving each. The Rutland Colliery tramway is named on the original map, while Messrs Jessop & Co of the Butterley Company had their ironstone tramway, which terminated at the goods wharf, is marked as C. They had started the ironworks about epetember 1846.

Across Bath Street, marked as D, are the Ilkeston Baths, while E are the buildings which made up the Rutland Hotel. There are separate premises at F, not part of the station (I believe) which could well be those belonging to James Chadwick whom we shall meet very shortly

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Railway improvements: 1866-68

In July 1866 improvements to Ilkeston Junction Station were agreed and commenced. The tender of Samuel Hunt, builder of Tithe Barn Lane, had been accepted…. he agreed to complete the work in four months.

In 1867 the expanded and improved facilities at Ilkeston Junction station were completed and the new station opened in November. The Derby Mercury reported that the new facilities were a few yards higher up the line than the old junction station and on the opposite side. However the construction of a new road (New Street) planned by the railway company out of Bath Street to this station — thus allowing people to walk down to the Junction — was not complete at this time. The passenger branch line to the Town Station was therefore retained until May 1870 — until New Street had been extended to the junction. (New Street was a name in use from about 1860 to 1870 when it was changed to Station Road).

Having secured a patent for his ‘novel invention’, in March 1868 William Manners of Nottingham successfully demonstrated his train communication cord in a private trial to representatives of the Midland Railway.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Railway problems: 1869

In 1869, shortly before the closure of the Ilkeston branch line, Samuel William Bond, a married man aged 24, was working as the horse driver on this line. He climbed on board a train which was being shunted at the Junction in order to uncouple a truck, not the job he was employed for and a highly irregular practice. Sadly his foot slipped, he fell between the trucks and his right arm was crushed. The injured man was taken with care to Nottingham General Hospital where Dr. T. Wright amputated his arm while the patient was under the influence of chloroform. Unfortunately ‘the shock and subsequent exhaustion’ were too much for Samuel William and he died the following evening. At the inquest the Coroner returned a verdict of ‘accidental death’ and censured John Allen, the railway guard/porter for allowing the deceased to uncouple the trucks — he should have known better whereas Samuel William had only held his position for a few months. From about 1847 chloroform had been used as an anaesthetic, having several advantages over ether which it gradually replaced. However it was when Queen Victoria was persuaded to use it in 1853, when giving birth to her son Leopold, that the chemical was widely accepted.

Just over three months after the death of Samuel William Bond the branch line horses were again causing trouble. Passing over the canal bridge on their way to the Junction two of the horses were startled, one fell over the bridge and was left hanging by part of its harness, pulling on the second horse and causing it to be pinned on the bridge. Workers at the nearby Rutland Colliery saw the incident and ran to help the railway workers to cut free the horses. Never reluctant to offer advice to the railway company, the Pioneer suggested that “it may not be amiss here to give the railway folk one word of caution. They ought not to attach stone and luggage wagons to the passenger carriages on this line, for it is a most dangerous practice. There is plenty of time to run them separately”.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

The 1870s

Railway changes: 1870-74

At the end of April 1870 the branch line from the town station to the Erewash Valley main line at Ilkeston Junction was closed to passenger traffic. The Junction station, renamed ‘Ilkeston Station’, now conducted all passenger business. At that time the branch line was described as having cost £23,000 to construct, and was 1500 yards long, with two bridges, one crossing the canal.

Letter to the Ilkeston Pioneer, November 13th 1873…………“OUR POSTAL AND RAILWAY SERVICES. Sir, the gross irregularity and mismanagement which characterises these services between Ilkeston and neighbouring villages is becoming a very serious matter for the trading interests of the district….. The passenger trains are punctual only in their irregularity. No wonder that accidents occur. To be 20, 30, 40, or 60 minutes late is a very regular occurrence. Only the other evening the last train to Nottingham did not reach Ilkeston until 11.45. “It is seriously proposed to send the mail bags by foot messenger to Nottingham, as a man could easily walk there and back, after making up the bags, in the time he has to wait of the train. Letters for Heanor, Belper, and other villages within an hours walk or drive of Ilkeston are frequently two or three days in transmission! And the despatch of the Railway Company is equally clever; for they often take as many days to deliver a parcel as it has miles to travel. Such instances of delay and neglect in the postal and railway services are as plentiful as blackberries in autumn; and this is what the public has to pay for having established such gigantic monopolies. Yours, very truly, A SUFFERER.”

In December 1874 the Ilkeston Telegraph announced the ‘new and improved’ arrangements for the passengers of the Midland Railway Company throughout its system, due to come into force in the New Year of 1875. In future there were to be only two classes of passengers – first and third – second class was to be abolished. The old third class carriages were to be upgraded with comfortable leather cushions, would have foot warmers for the winter, and would be almost identical with the present second-class carriages. It was hoped to provide higher compartments to ensure better privacy and protection against draughts. The fare for this class was to be reduced to be less than that of the ‘old’ third class. The first class carriages would remain unchanged but their fare would be reduced. “A sufficient supply of Pullman cars will be provided for those who object to mix with that proportion of second class passengers who will avail themselves of the superior accommodation afforded by the reduced first-class, or who may have better reasons for requiring greater comfort and privacy. For long journeys the sleeping cars will be a great convenience”. The Ilkeston Telegraph anticipated that the other railway companies would follow suit. However, rather unconvincingly, the Pioneer was soon suspicious of the changes, and in particular their effect upon the old second-class passengers. These passengers would now be faced with a choice of ‘three courses’; to travel first class and thereby pay more than they were previously; to travel third class; or to stay at home !! The newspaper did concede that both the new first and third class passengers would derive benefit, and seemed to be ‘scratching around’ for a stick to beat the railway company with. It concluded that the company’s new policy was “a delusion, a mockery, and a snare”. (IP January 1875) Just over six months later the same newspaper was reporting a substantial increase in passenger numbers for the Railway Company since January, resulting in increased revenue of over £50,000. Receipts per mile of passenger trains were the best they had been for 25 years. “These figures read very like convincing testimony in support of the policy lately adopted by the directors of this Company”. And in his ‘Local Gossip’ column for the Pioneer, ‘Tatler’ wrote “I rejoice to find that the half-year’s report of the Midland Railway Company is such an ample justification of the liberal and far-seeing policy adopted by its directors”.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Railway crime: 1875

P.C. William Colton was on duty just before 4am. one Sunday morning in May 1875, patrolling near the Town Station, when he spotted old James Tomasin, horse breaker of Brussels Terrace, approaching some coal wagons in the Butterley Company’s sidings there. Following at a distance, he spotted James break up a few lumps of coal and put them into his basket. When challenged by the law the old man replied that he had no coal at all in his house. For this reason the magistrates at the Petty Sessions felt sorry for James, sentenced him to seven days in prison but without hard labour, though if he had not had a good character and been an old man he would have spent longer in jail. Born in Shardlow John was then 66 years old, had lived in Ilkeston for 40 years, and had initially worked as a groom, but as his family increased along with the financial burden upon him, he had sought more lucrative employment as a labourer. He was thrice married and claimed to be the father of 20 children – ten of each sex – whom he had brought up without any parish assistance. Five of his sons had gone into the army – two had died and three were still serving.

Autumn 1875. Missing from Ilkeston and Long Eaton Stations …. presumed stolen. 26 boxes of cigars and 20 bottles of liquor, one cwt. of sugar, a quantity of raisins. a chest of tea destined for Mr. Isaac Gregory, grocer of Bath Street. carpeting, sheets, a dozen shawls, 30 pairs of stockings, clothing, scarves, handkerchiefs, knives and forks. approximately £50 in gold.

Stop Press !! October 1875. All the above items have been recovered … found in the hands of furnaceman George Wimbush, engine driver John Allen, aged 26, shoemaker William Jacques, aged 31, and shoemaker John Stephens, aged 26. … in properties at William Street and Tutin Street in Ilkeston, and at Pye Bridge near Alfreton.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

The Midland Railway responds to competition: 1876-79

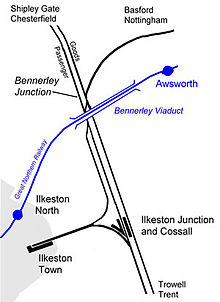

By 1875 the Midland Railway had a competitor in Ilkeston in the form of the Great Northern Railway which was making its prescence felt ….

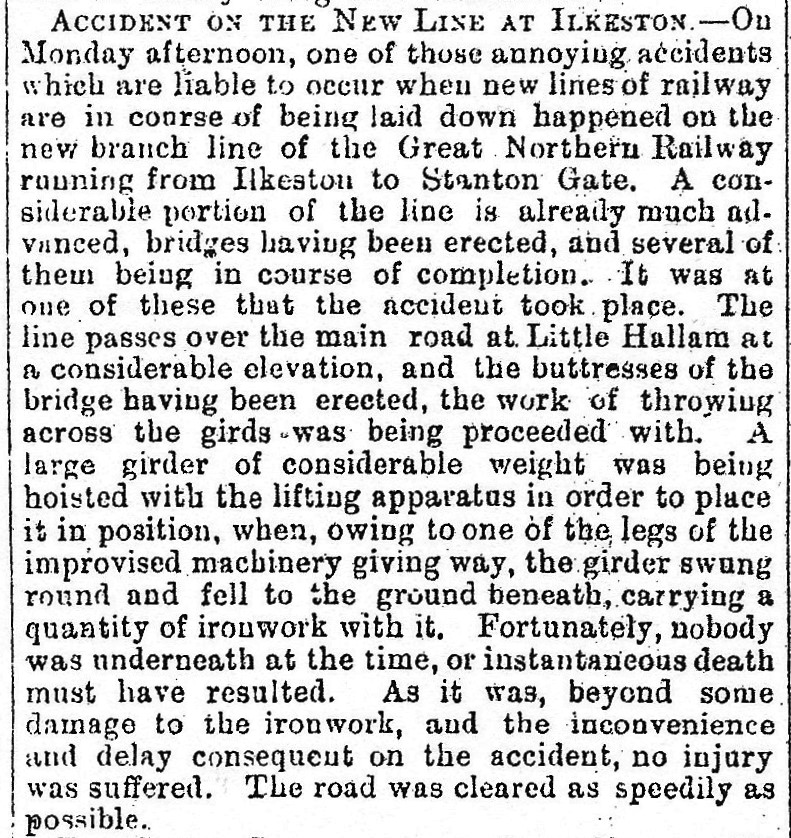

Railway contractors Messrs Benton and Woodwis, requested … to allow Ebenezer Street to be stopped up during the time the new railway line for the Great Northern Company was carried across the street … which belonged to the Duke of Rutland (Derby and Chesterfield Reporter Oct 8th 1875)

And a year later the Ilkeston Pioneer (Oct 26th 1876) reported that the new line was making ‘considerable progress’ between Awsworth and Ilkeston. “The iron viaduct, by which the line will be carried across the Erewash Valley and the Midland Company’s Erewash Valley line, with the various bridges, embankments, &c., are steadily progressing towards completion”. (This viaduct is today referred to as the Bennerley Viaduct) It also reported on the new bridge situated on Heanor Road, allowing that road to travel over the new railway line … it was now complete and open to traffic. What remained to be done was build walls either side — to ensure that no-one fell onto the line ?? A new station was also being build — later known as ‘Ilkeston North’.

Unfortunately one labourer employed by the Great Northern, working on the line between Ilkeston and Derby, didn’t see its completion. George Wade, aged 35, had been lodging at one of the navvy’s huts at West Hallam, and on October 16th 1876, he left his lodgings to have a drink or two at the Miner’s Arms on Derby Road — his body was discovered four days later floating in the Nutbrook canal, near Moors Bridge. A boatman had been through the canal lock there and couldn’t shut the gate after his passage. He enlisted the help of canal labourer Charles Pounder to remove the ‘obstruction’ — which turned out to be George’s body. Was he returning to his digs when he failed, fatally, to navigate the canal ??

The Ilkeston Pioneer was overjoyed by the prospect of an alternative to the Midland Railway …..

The Great Northern Railway intend opening their Derby – Nottingham line for goods only. It will be a great convenience to residents, manufacturers and the like. Ilkestonians know only too well the privations, delays and disappointments they have long endured at the hands of the Midland Railway, not to feel thankful for the prospect of being better served in future — whilst the once distant hope of being able to reach their chief County Town in something like reasonable time draws daily nearer realisation, it being understood that a passenger service will commence in about three months time. (Jan 1878)

However the Midland would not stand aside easily !! In May 1878 notices appeared asking for tenders for the erection of a new passenger station and goods warehouse at Ilkeston. And in June/July 1878 the old Town Station house and its stables were pulled down as the Midland Railway was about to erect their third station since the formation of the Erewash Valley line.

A ‘new, improved and enlarged’ Town Station was opened in July 1879, mainly for goods traffic with restricted service for passengers. This was to meet the challenge from the Great Northern Railway which had conveniently chosen to site its station on Heanor Road, behind the ‘extensive factory of Messrs Hewitt‘, ‘a field in the occupation of Mrs.Twells‘. At the same time a bridge, constructed from iron girders, was built across the line, connecting the northern end of North Street to Rutland Street. There was also talk that the Great Northern Company was interested in buying the Baptist Chapel in Queen Street in order to build a station on the site, connected to the main line by a branch line. “The carrying out of such a project would be a great convenience and saving to the whole south end and centre of the town”. (IP May 1879)

The Midland Railway Company; Revised Timetable, on the completion of the Town Station. July 1879. There are now three trains daily, each way, between Ilkeston and Nottingham, though five on Wednesday and seven on Saturday – the market days. On ordinary days no journey will occur during the ‘busiest part of the day’ – breakfast time to tea time. During this period passengers will still have to hike down to the Junction Station or use the Great Northern line. No Sunday service to or from the Town Station. The last train from Nottingham leaves on ordinary days at 5.20pm.; on Saturdays at 8.55pm. The last train to Nottingham leaves at 6.10pm. on ordinary days; on Saturdays at 9.35pm. With the Great Northern, the Midland Railway Company now provides a total of 21 trains each way on ordinary days, 26 on Wednesdays, and 28 on Saturdays. Journey time to Nottingham is 23 minutes — compared to the G.N. which takes 26 minutes.

By February 1880 two bridges on the Great Northern Railway line had given way at their foundations, reportedly owing to mining operations beneath the surface.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

The 1880s

The Town Station and surrounding area c1880

Present and future: 1881

And writing in the Nottinghamshire Guardian, November 1881, an ‘Occasional Correspondent’ noted that….

“as far as material prosperity is concerned, however, few places in the valley are (Ilkeston’s) equal. Situated on the southern side of the great Midland coalfield ….. two railways run through it, and in the way of coal transit confer all the advantages it could reasonably desire. In the way of passenger traffic, however, the like remark by no means is applicable. Still, as might be expected, the amount of that traffic is very considerable, while that of coal traffic by the Erewash Valley, per month, is steadily increasing. For instance, in September last the amount of coal, & co, sent on the Erewash Valley line from Ilkeston, was 19,272 tons, showing an increase of 7,184 tons over the corresponding month in the previous year, notwithstanding the competition which is experienced from the Great Northern line from within its limits. The number of passengers for the same period from Ilkeston station (Midland) was 7,716, showing an increase of 933”.

And looking to the future the same writer prophesied that…

“the coal field in the valley being at present comparatively unworked, and its proximity to the metropolis and the southern and eastern counties, are advantages which tend to the belief that, great as has been the increase in the population of the valley, and rapid as has been its development, it is only probable that the district will in a few years become one of the busiest, richest, as well as most populous, in the kingdom”.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Accidents will happen … May 1883

..….. and July 1885.

Imagine the scene on the station platform at Ilkeston as the fast train from Trent to Sheffield approaches. Staff officials are preparing for the stop, as are the passengers on board the train who are about to alight. And what happens ? The train flashes by, no stop, and continues upon its uninterrupted way .

The engine driver was new to the route and unaware that the train was scheduled to stop at Ilkeston on that Tuesday evening. Only later realising his mistake, he pulled up at Langley Mill, four miles away; the passengers then had to make their way home as best they could.

The 1890s

…. and January 1890.

The Rev. James D Alford, Baptist Minister from Aston, Warwickshire, was travelling comfortably in the slow train to Ilkeston, where he was to address members of the Liberal Club in their Market Place headquarters; the subject of his talk was to be financial reform. He was due to arrive soon after six o’clock, and as the train pulled into Ilkeston Junction station, he sat back, expecting it to take him on to the Town Station. However the Rev. gentleman hadn’t mastered the puzzling arrangements of the Midland Railway Company, and he very soon found himself at Shipley Gate Station !!! Perhaps at this point panicking somewhat, he was forced to employ ‘Shank’s pony’ to get to his destination.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

A new line from Ilkeston: May 1890

The Great Northern Railway extension of 3¾ miles between Ilkeston and Heanor Gate was commenced, using 200 men and 20 horses at the Heanor end. Several bridges had already been partially constructed and the opening was scheduled for the end of the year. A short line from the Heanor end to a new line to Nutbrook Colliery had been completed. The station at Heanor would be within half a mile of the centre of town.

In fact, the end-of-year target for completion was not met. On Monday, April 13th 1891, the last rails were laid, the occasion being celebrated by a group of about 50 workmen taking a short trip along the line. It was now aimed to open theline to passenger traffic in the next month. However the formal opening for goods and mineral traffic took place on June 1st, while the opening for passenger traffic was slated to be July 1st. And spot on time — this time — it was duly opened on July 1st, The first train left Heanor at 8 o’clock, carrying 50 passengers, cheered on by hundreds of spectators.

Seven trains each way per day were planned.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

September 1890: Station improvements

The Midland Railway had designed plans for improvements to both the Town and Junction stations. These included new waiting rooms, the covering in of the Town platform and the road to it, and a similar covering for the Junction platform.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

November 1891: What’s the link between Cotmanhay Farm, the Great Northern line and Ilkeston Fire Brigade ?

About half past ten at night, on November 2nd, the Fire Station received a message that stacks were ‘raging’ at Joseph Attenborough’s Cotmanhay Farm. The Brigade was quickly on the scene, to find two stacks — one of oats, one of barley — on fire. The flames was quickly contained and did not affect other nearby stacks, but the produce of seven and a half acres of land was ruined. The damage was fully insured !!

It was initially thought that a spark from an engine on the Great Northern Railway had ignited the fire…. except that the wind was blowing in an opposite direction to account for this. Incendiarism was therefore suspected.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

June 6th 1894: Suicide on the Midland line

Employed by the Midland Railway Co., engine driver Joseph Stirland of Nottingham left Trent Station at 6.52 am in charge of a passenger train to Sheffield. Between Trowell and Ilkeston Junction, at Cossall Crossing, travelling about 20 mph, he saw a man standing between the up and down lines, about 100 yards away. He whistled, shut off the steam and shouted to the man to clear the track. The man could easily have got out of the way but as the train was about to pass him, he stepped into its path. A nearby platelayer, Frederick Stevenson, was warned of the accident and quickly went to investigate. He found the man lying on the line, his coat over his head, injured and bleeding from his head and hands. Though still alive, by the time he had been transported to the Town Station he was dead.

At that time no-one knew who the man was. Described as ‘poorly-dressed, apparently about 60 years old‘ with nothing on his person to identify him, though on him were found a razor, a knife, a purse containing a little tobacco and an old clay pipe. There was no letter. The body was taken across Bath Street, to the Rutland Hotel, to await the inquest the next day at the Mundy Arms.

By the time of that inquest the deceased had been identified. He was Joseph Stevenson, a previous colliery labourer, aged 68, living in Grass Street with his daughter Sarah Ann and her husband James Gregory. His family said that he had not worked for the last two years, and received 2s 6d from his lodge and 2s from the parish, suffered from rheumatism and had been drinking rather heavily lately. His wife, Mary Ann (nee Scattergood) had died a couple of years before and since that time Joseph had seemed very restless. Sufficient to explain the suicide ?? The jury thought so and returned a verdict of ‘Suicide while temporarily insane’.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

December 1897: a passenger retaliates

It would not surprise you to read of a passenger being charged with using a first-class carriage while buying only a third-class ticket. That is precisely what happened to Gerard Arthur Kennaway, a civil engineering student at Shipley Collieries who found himself sued by the Midland Railway Company for 1s 7½d excess fare. In June of 1897 and armed only with a third-class season ticket he had been discovered using the comfort of a first class seat. Gerrard admitted the ‘offence’. However he then offered a counter claim. On two previous occasions while travelling with the same company Gerrard had had to endure great discomfort because the Company had allowed more than the proper number of passengers into the third-class area. He had been forced to stand for most of the duration of the journeys, and he thus counter-claimed for ‘damage, inconvenience and annoyance’. … and he had case law to support his claim !!

December 1897 and at the Ilkeston County Court, the Midland Railway won its claim for the excess fare, while Gerrard was awarded 2s 6d ! And there was no leave of appeal granted to the Company. The verdict summary stated that the House of Lords had laid down that a passenger was entitled to reasonable accommodation, and that it was the duty of the Company to see that such accommodation was provided.

1898 Beware Level Crossing: Danger of Death

The branch line between Ilkeston Town Station (off left) and Ilkeston Junction (off right)

The level crossing was situated at the junction of Rutland Street and Belfield Street. Since the opening of Chaucer Street schools in 1889 it had been used by children attending those schools but living in Rutland Street and the surrounding area to get to their education. One such child was eight year old Beatrice Horsley, daughter of coalminer Robert Enoch and Sarah (nee Bostock), living at 36 Rutland Street.

At about 9am on April 22nd little Beatrice ran through the hand-gate at the crossing and onto the line, just as the 8.58 train from the Town Station had departed for the Junction. On duty aat the crossing was Joseph Biggerdyke who twice called to Beatrice to ‘stay there’. The lass did stop but as Joseph was looking the other way to see if the line was clear, she took a step forward. The train buffer caught her head and knocked her underneath the engine; she was killed immediately. Sadly the accident was witessed by father Robert Enoch, returning from his garden close by, although the engine-driver and fireman were totally unaware of the accident, seeing the line being clear as they approached the crossing.

The subsequent inquest recorded the verdict of “Accidental death” but added a rider that the Midland Railway Company be asked to provide some means of automatically closing the gates from inside the signal box.

A few month’s after her daughter’s death, Sarah Horsley gave birth to another daughter who was registered as ‘Beatrice Horsley‘.

May 1898 … and yet another Committee

The people of Ilkeston loved committees, and by May 1898 another one had been formed — for the Promotion of better railway facilities for the southern end of Ilkeston. On Wednesday, May 25th, its members met in the South Street Sunday schoolrooms to report any progress that had been made. George Haslam, the chairman, relayed that he had met with Charles Steele, general sub-manager of the Great Northern Railway, and had a frank exchange of views. Charles explained that, with the company’s recent joint occupation of Nottingham Great Central Station, there were now various improvements in the locality under consideration. Sounds like waffle to me !! It sounded like waffle to George too, and he expressed the view that these ‘improvements‘ didn’t affect the matter in hand. Thereupon Charles suggested the Committee should conduct a survey and produce a memorial to present to the Company; then he would see what could be done.

At the end of the meeting George was asked by the Committee to consider what further steps needed to be taken.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Late October 1898: a small collection but a very long speech

The town saw a meagre procession of members of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (excuse: it was raining heavily) as they made their way to the Parish Church, headed by the band of the Ilkeston Volunteers. The afternoon street collection, in aid of their orphan fund, had been very poor, and it wasn’t much better inside St. Mary’s. A total of £6 19s 3d was raised.

In the evening the same group attended an ‘open meeting’ at the Derby Arms of landlord Councillor Joseph Kirk where they listened to several speakers. The first was Mr. Scott, the well-known goods guard representative reporting on the theme “What has been accomplished in the past, and what remains to be accomplished in the future”. Like his title, the speech extended beyond the normal and severely tried the patience of many listeners there. He started his ‘historical reflections’ 20 years before, drawing the conclusion that shorter hours and better pay had been achieved over that period, and by the actions of the A.S.R.S. the level of safety on trains had been increased. Peppering his speech with an abundance of statistics, he would have proved his case, had the audience followed his reasoning — though that is far from certain !!

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

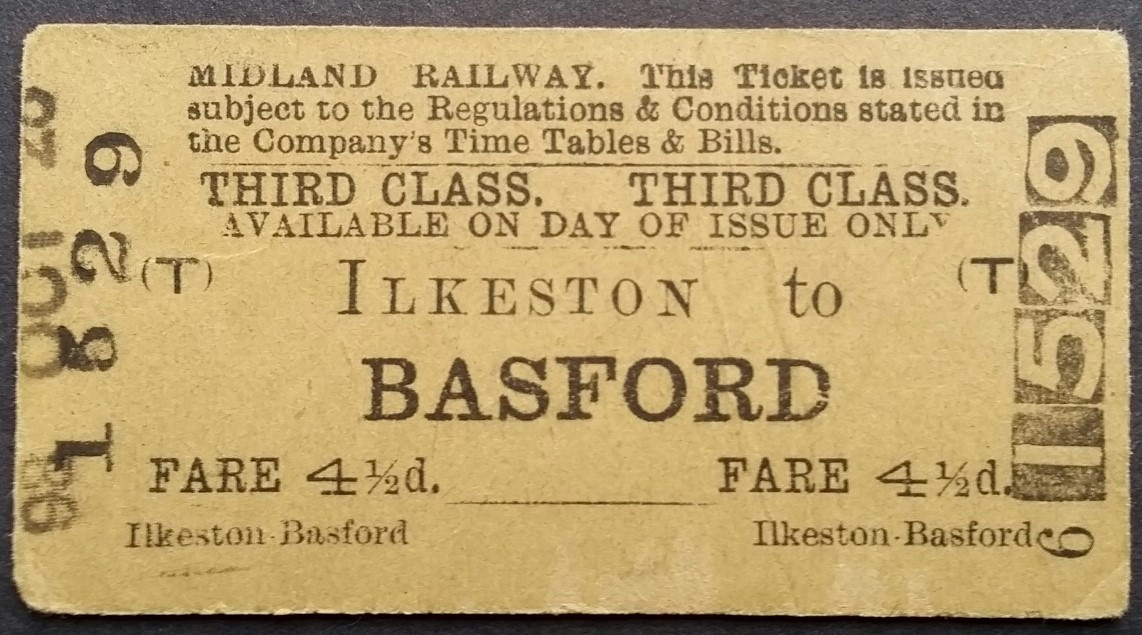

1898… want to travel to Basford ??

Courtesy of Andrew Knighton

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

January 1899: and would you believe it ??! Yet another Committee !

January 18th and a public meeting at the Jolly Colliers Inn in Cotmanhay, this time to discuss a new station on the Midland Railway at the northern end of the town. This issue had been raised in 1890 when the one problem which could not be overcome was the making of a bridge over the Erewash Canal so that an approach to any new station could be made. The Midland Railway Company was willing to build the station if the landowners in the area would provide the approach. The estimated cost of the bridge at that time was £900 and Bennerley furnaces had promised to provide the slag to make the road, but thee cost was the main stumbling block.

At this 1899 meeting Councillor Richard Hunt proposed that the Town Council should make a substantial contribution to this scheme. The railway line was about to be widened with two more lines and so something needed to be decided quickly, before these alterations were started. William Manners Manners represented Mr. Davis, the owner of Bennerley furnaces, and he suggested that, as the householders in the area would have the value of their properties enhanced, they should all do their utmost to get the scheme started.

The discussion terminated in the formation of a committee !!

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

And before we continue our walk up Bath Street, we consider a short postscript to the Town Station.