“Below (Francis Sudbury) also built a cottage which was occupied by Mr. John Fish, who, in later years became Parish Clerk at St Mary’s, following old Mr. Whitehead.”

John Fish was born on July 15th 1822, son of boatman labourer John and Esther (nee Dennis) who lived at Hungerhill.

John the Oddfellow

Initially following his father’s trade, John converted to framework knitter and worked for the Sudbury firm for many years, being made its manager in 1858. When he left that firm he worked as a house agent and rent collector.

John joined the Britannia Lodge of the Grand United Order of Oddfellows on its opening night, March 17th 1845, and in 1851 became its District Secretary, an office he was to hold for over 30 years.

Two years later he was made a member of the Grand Master’s Council and in 1861 was elected onto the Committee of Management of the Order.

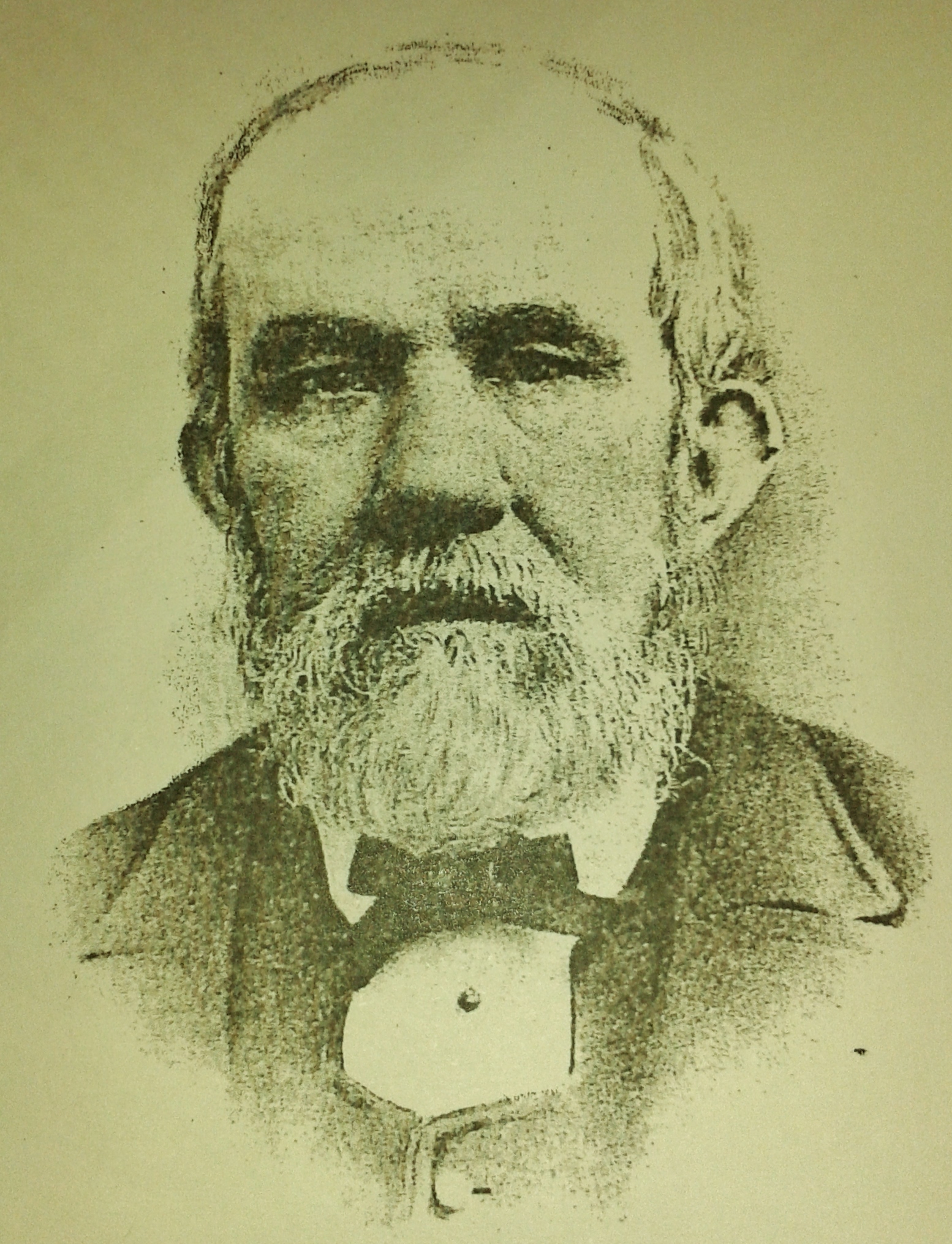

In 1889 his portrait appeared in the “Quarterly Magazine of the Order”.

He was also a member of the Rutland Lodge of Freemasons.

(The first Permanent Grand Master to the Order was Samuel Potter of the Park. When he died the post was transferred to the Rev. George Searl Ebsworth who left Ilkeston in 1863. His successor, the Rev. James Horsburgh, then held the post for almost ten years and when he left the town in 1873 the post was filled by Samuel Streets Potter of the Park.)

John the Parish Clerk

In 1863 John was appointed Parish Clerk, a post he was to hold until the end of 1895, when he resigned.

The previous holder of that position was Samuel Whitehead.

At about 11am on February 9th 1866 John responded to a knock at his door in Queen Street to find himself facing Elizabeth Henshaw (nee Morley), wife of coalminer Thomas. She had come to ask if John would bury a stillborn child. John agreed and the couple arranged to meet in the graveyard of St. Mary’s Church at about 4 o’clock that afternoon.

John had already dug a small grave when Elizabeth arrived at the scheduled time, clutching something that looked like a grocer’s raisin box with a nailed-down lid. As he was burying it, Elizabeth intimated that there were two infants inside, which would, of course, mean a double fee to be paid.

Ten days later, as the Registrar of Births and Deaths, George Blake Norman called at the home of stone-getter John Thompson and Hannah Thornhill to establish details of a recent birth at the house. He was told that a boy and girl had been born there, about six weeks prematurely, on February 8th but both had died the following day. These were the infants buried by the Parish Clerk.

Elizabeth Henshaw had assisted at their births which had taken place in the early hours of the morning.

In the evening of that day, Hannah Thornhill had been visited at her home by an acquaintance, Louisa Kelly, who found the new-born twins lying close to a small fire, on a piece of old rag in a bonnet box and covered only by a narrow band of calico around their waists. She had brought with her a napkin, a tablecloth and a piece of window curtain to help clothe the children but the ‘midwife’ Elizabeth had not used them.

Louisa returned a couple of hours later with a basin of gruel for the mother who was lying on some sacking on the floor, with no pillow or bolster, apparently naked but covered by a quilt, and attended by Elizabeth Henshaw and a neighbour. There was no light in the house and the fire was dying. Stone-getter John had left to fetch a lump of coal. Although both children were alive and crying at that time, neither had been further clothed and the boy appeared quite cold and very weak. The girl was in the bed with her mother and was fed with a little tea.

Both babies died that night, in cold and dark surroundings, hungry, unclothed except for rags, and unnamed.

These details emerged at an inquest held at the Market Inn on February 18th, after the two bodies had been disinterred and examined by Dr. Norman. He reported on their external appearance, testified that there were no signs of physical violence or disease, but could give no cause of death. The inquest jury then asked him to conduct a post mortem examination which he promptly did, returning a short time later to confirm what he had already stated but now giving the cause of death as ‘debility’…. the babies had received little if any food, had not developed sufficiently and were just too weak to survive.

Elizabeth Henshaw was admonished by the Coroner for the inadequacy of care she gave to the twins, especially over their lack of clothing, and for the way she had lied to the Parish Clerk.

“The children had not died from want, but from neglect, and the case was a most disreputable one. He must advise her to be more careful for the time to come”.

Elizabeth, who appeared to be a decent person, argued that she did not know where she might go to get clothing for the infants … the Coroner replied that anyone would supply her with anything that was necessary for the asking. Perhaps Elizabeth’s experience and expectations were far different to those of Coroner Whiston.

On behalf of the members of the jury — all men of course — who had been visibly harrowed by the evidence they had heard, the Coroner went on to thank both Louisa Kelly and neighbour Maria Raynor for the concern and kindness they had shown. The latter had taken the shirts off her own children’s backs to wrap the infants in.

At Ilkeston Petty Sessions, Elizabeth Henshaw was later fined for her actions, not for her treatment of the babies while they struggled for life, but for her procuring an unlawful burial.

Six weeks after the inquest John Thompson and Hannah Thornhill — neither natives of Ilkeston — were married at St. Mary’s Church. They lived at Ilkeston for a few years where daughter Mary Ann was born in 1870 before they moved to Yorkshire, and stayed there into the next century. On the 1911 census they appear at Denaby Main, Rotherham, living with their two surviving children, Mary Ann — who in 1891 had married coalminer Albert Firth — and unmarried son William.

Both children are, however, counted twice on this census — they also appear together, a few miles away, at Worbrough Dale, Barnsley.

From 1837 until 1874 it was the task of the Registrar of Births and Deaths to travel around and actively search out any household where an event had taken place, to record the details. There was no penalty for non-registration of a birth or death and many parents thought incorrectly that baptism was a legal alternative.

The Births and Deaths Registration Act of 1874 made registration compulsory, placing a duty on those present at a birth to register it, while a relation of a deceased was to inform the registrar.

There was a separate registrar for marriages.

John the Clock Winder

There had been a town clock at least since 1740, and it was the job of the Parish Clerk to keep it in working order and on time –for which he (invariably ‘he’) was paid.

In 1866 John Fish requested a small annual salary for winding up the church clock, a task he had performed since 1864. (A public subscription had financed the purchase of a new church clock in 1863).

The Local Board informed John that they had no funds for such a payment. However the following year he was awarded an annual salary of £4 for ‘winding, oiling, cleaning, and keeping the clock in proper going order’.

In 1872 the Local Board received a letter from the Local Government auditor informing the Board that it had no power to take over the Church Clock, and nor could the Board pay for any repairs …. it was all laid down in the Town Clauses Act, so there !!! At this time the Board argued that it didn’t pay for the cleaning of the clock, just for its winding up.

In October of 1874 ‘The Church Clock’ wrote its own pleading letter to the Ilkeston Pioneer.

Sir – Though young in years, I am almost ‘run down’, and that must be my excuse for troubling you with my ‘complaint’. Rheumatism has so affected my joints that I cannot even move my ‘fingers’; and I am sadly troubled with asthma.

No doubt my good neighbours have noticed how weak my voice has been several times during the last few weeks , and now I cannot speak at all. I have been visited by my old doctor, but he says this is the worst attack I have ever had; and so I must wait, like a ‘fish’ out of water, until the weather becomes more genial, and then it perhaps may thaw my frozen limbs, so that I shall be able once more to speak out in the same clear and silvery tones I was accustomed to do in my younger days.

Might I suggest that a sweeping-brush be added to the few articles I possess, for although my friends have kindly placed me under the protection of a glass case, my breathing is so bad that the least particle of dust almost chokes me.

Some people would call me a ‘gambler’ – sometimes I gain heavily, and at other times my losses are considerable. The fact is, I want regulating; it is very seldom now that I can hear of Greenwich; so that I cannot be trusted.

Hoping that some one will kindly give me a start, allow me, Sir, to remain, Yours, in silence.

P.S. – Since writing the above, I have received a new lease of life, but I am afraid it will not last long, as my last attack has left me extremely weak.

By May 1881 the Local Board’s auditor had objected to the ‘clock-winding’ payment made to John and this had now reverted to a public donation. Some clearly felt that, as the clock was church property, it should be maintained by church funds. But now neither the Local Board nor the churchwardens would pay John. The ‘winder and oiler’ had not been paid for 15 months, and he had already paid £3 15s out of his own pocket to rewind the clock.

He could afford this no longer.

So in July 1881 the clock stopped!! (Just as the Ilkeston Advertiser started!!)

And town poet William Campbell was once more inspired…

“MOTHER CHURCH’S CLOCK.

Poor old Mother Church! we pity thee much,

Since thou art so poor, and thy poverty such,

As regret it we may,

Because they own clock at the top of the hill

For want of the needful is now standing still,

Pointing wrong all the day.

Its fingers so richly emblazoned with gold,

In charge of the Priesthood true time must be told,

Without further delay,

Appointed officials must see the clock right,

Churchwardens are they who are adequate quite,

And Churchwardens must pay.

(as it appeared in the Ilkeston Advertiser July 23rd 1881)

Something had to be done! A radical plan was needed!

Step forward Charles Potts who within a month had secured public subscriptions of £10 13s 10d towards the Parish Clock’s expenses.

In October 1887 the issue of illuminating the clock by gas was raised by George Haslam at a Town Council meeting. Noting the role paid by public subscription in the existence and maintenance of the clock, most now felt that it was public property, a fact that the new Vicar and the churchwardens agreed to sign up to. The ‘maverick’ councillor Charles Mitchell opposed the proposal — following his usual pattern of opposition — and argued that what was done for the Parish Church should also be done for all the town’s chapels. The motion was, however, decisively carried.

John the Property Owner

In April 1875 John Fish moved out of Queen Street into Market Street. He had property close to Derby Street and later in the year — with John Goddard of the Anchor Inn — he sewered and channelled part of that street and applied to the Local Board to recognise it as a public street.

For the time being the Board refused, until the rest of the street had been developed.

Then, in the Spring of 1876 the following appeared in the Ilkeston Pioneer …

Notice is hereby given that the building lately used as a Girls’ School, situated in the Market Place, Ilkeston, will on Thursday April 13th 1876 be opened as a Market Hall in the place of the old building just taken down.

By Order, John Fish, Market Superintendent and Collector

In the autumn of 1887 the old Girls’ School building was eventually purchased by the Town Council as a ‘Market Hall’. And thus, in later life, John made it his home.

John got further good news at the end of February 1888, when it was announced that the Duke of Rutland had offered the use of the Market Place for an anual rental fee of £100 — so long as they granted John a compensation of £150 and let him live rent-free at the hall for the remainder of his life (or compensation in lieu). And just in time !! … the Duke died a few days later, on March 4th.

John died in the Market Place on May 29th,1896, aged 73. Following a service at St. Mary’s Church, John was buried in Park Cemetery, the burial attended by a good number of Freemasons and Oddfellows.

“Mrs. Fish took in work from outside workers.”

Since February 1851 John had been married to Elizabeth Beardsley, daughter of Hungerhill framework knitter Richard and Mary (nee Hawley).

She died in their Market Place home in January 1895, aged 74.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

John’s brother William

One of John’s younger brothers was William Fish born in 1828.

About 7am one dark Tuesday morning in February 1881, whilst living in Derby Road, he was walking to start his work at the ironworks of the West Hallam Coal and Iron Company where he was a labourer.

The rough wind beat the rain into his face as he crossed a railway line running through the furnace yard, and he moved aside as he heard the warning whistle of a shunting engine.

Unfortunately he stepped into the path of another shunting rail truck.

William died immediately.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

Below John Fish was Frank Hallam’s Row