Ilkeston’s church bell-ringers had long been paid — for ringing on Christmas Day, New Year’s Day, and November 5th.

The First Team.

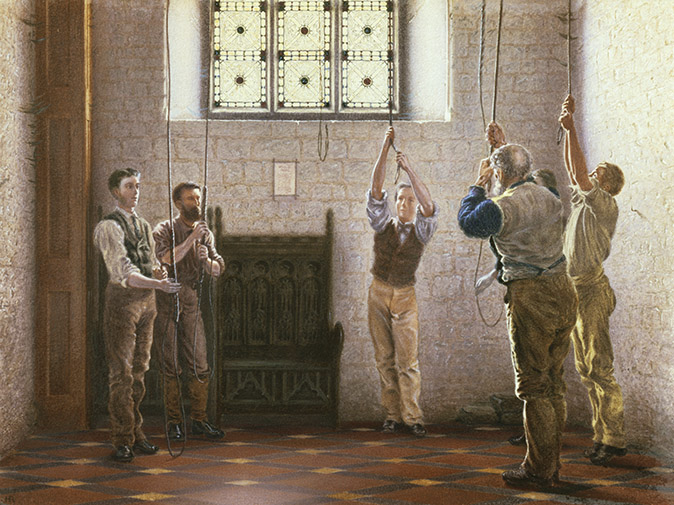

In 1860 there were five bells in the church and a visit to the Belfry in that year would have revealed, on the south wall, written in lead pencil (as recalled by Gisborne Brown), a verse….

Five men there are who jang these bells,

Read this verse, their names it tells;

There’s Tatham Jack and Severn Tom,

And ‘Lias Brown, when he can come;

Tom Meakin’s broke his leg, alas !

And then there’s little Silly Ass!

The five men were:

John Tatham, aged 35, lacemaker of Chapel Street (second bell). He resigned in December 1874.

Thomas Severn, aged 40, carpenter of Severn’s Yard, High Street (third, and conductor)

Elias Brown, aged 35, lacemaker of Trueman’s Row, Burr Lane (tenor)

Thomas Meakin, aged 34, lacemaker (later plumber and glazier) of Albion Place (fourth)

Silas ‘Silly Ass’ Spencer, aged 30, mechanic of Park Road (treble).

In 1869 Silas was working as an engineman at Butterley Company’s ironstone pits on Ilkeston Common when he was trapped in the engine flywheel which then carried him around for a couple of turns before it was stopped. Silas was severely cut and his left thigh, leg and the region of his bowels were seriously crushed.

The Pioneer feared for his life, reporting that an engineman at the same pit lost his life in a similar accident about a year ago while the Derby Mercury stated (prematurely) that Silas had suffered the same fate.

The Ilkeston Telegraph entertained “serious fears…of a fatal result. Spencer himself fully appreciates his position and has given up all hope of recovery”.

Forty three years later Silas died, October 8th 1912, at 161 Nottingham Road, aged 84.

Eight years after his ‘near-death‘ experience Silas was in trouble once more — this time with the law. In September 1877, and still working as an engine-tenter, Silas had been visited at his home on two occasions by Police-constable Holland, (in a private capacity), when each time the latter had bought a cucumber and a pint of ale — and had paid for both !!! Silas seemed to be selling beer without a licence. Accompanied by a search warrant, the police later visited Silas and discovered several spirit bottles, soda water bottles, mugs, and four 18-gallon barrels in his cellar, three empty and one half-full with ale. Silas argued that although he had sold the cucumber to Mr. Holland the ale was a free gift.

At a subsequent Petty Sessions, the magistrates were highly suspicious of Silas’s explanation — unbelieving might be a better description !! — but as he had not been convicted before, they would treat him leniently. Silas was fined in total £2 3s when he could have been subjected to a penalty of £150 !! He did however lose all his confiscated drinking utensils and ale.

Silas, born in 1829, had a younger sister, Jocantha Spencer who was born on January 14th, 1841 … both were the children of James Webster ‘Jemmy’ Spencer and Sarah (nee Siddon). Jocantha married lacemaker John Trussell on New Year’s Eve of 1861 and almost one year later she was dead. Her short life started in Park Road, was lived there for almost all of her 21 years, and ended there. One month after her marriage she had given birth to a son, William Trussell.

When widower John remarried to Mary Ann Sophia Pinder in 1867 he fathered seven more children, but didn’t seem to have room at his home for his first child William who went to live with his uncle Silas at Belper Street. And it was while there that William married Amelia Carrier on November 27th, 1881 (one of the Station Road Carriers). But history was ready to repeat itself … almost. In 1883 Amelia gave birth to a son, William Trussell junior, and then died soon after. When widower William senior remarried to Elizabeth Dalley in 1885, he fathered at least six more children, but didn’t seem to have room at his home for his first child William junior who went to live with his granduncle Silas at Belper Street.

In the summer of 1895 William was still living with Silas when the pair got into trouble with the School Board. William hadn’t been attending school regularly and, as a consequence, Silas was hauled into the Petty Sessions to explain. He tried to pass the blame onto William’s father but when it was shown that the child lived with his ‘guardian’ Silas, then it was Silas who had to pay the fine of 5s.

By 1899 William Trussell junior was 15 years old and had long left school though he was still living with his granduncle Silas … and still getting into trouble. In January he was at the Petty Sessions where he was charged with stealing 10s worth of old iron from Silas !!! And according to Silas it wasn’t the first time. The lad had refused to work and had robbed his “grandfather” (as Silas was described in court) before. Silas had brought him up since William was an infant, but now he was rid of him. The lad was sent to prison for 14 days, to be followed by detention in a reformatory until he was 19 years old.

In 1896 Silas was working as a ‘house agent’ … basically a rent collector. One of the’properties’ he was caring for was a collection of gardens belonging to Samual Patrick Derbyshire, who had lived in Stanton Road but was now residing in Nottingham. Silas had rented the gardens from Samuel at an agreed rent, and was then allowed to sub-rent them to anyone he chose. A simple process you might imagine, and so it was … until bootmaker Nahum Ironmonger, now living in Stanton Road, threw a spanner into the works. Nahum had rented one of the gardens privately from Samuel and had agreed to pay the rent in the form of goods. When Nahum refused to pay Silas the full rent for the garden, the ‘agent’ deducted that amount from the rent he passed on to Samuel. This was not the agreement however; Silas had agreed to pay the full rental amount for the gardens, whether or not he had collected it from the sub-tenants. As a consequence everyone had to attend the Ilkeston County Court where, once more, Silas found himself out of pocket when he had to pay the full rent to Samuel.

‘Sitting on the bench’ as reserve ringers were John Hazledine and James Severn.

In 1867, at the death of framework knitter William Pollard, aged 80, the Pioneer noted that ‘for many years and up to the week before his death’ he was a bell-ringer at St. Mary’s Church.

The Peals.

In November 1875 a ‘Loyal Parishioner’, writing in the Pioneer, was quite put out by the fact that the Parish Church bells had not been rung to celebrate the birthday – November 9th – of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales.

He sarcastically suggested that the bell-ringers might be too fatigued from recent exertions, though he was more inclined to believe that they only pulled on their ropes if they had been paid beforehand to do so. To support his view the ‘Parishioner’ thought that he could detect a pattern in their behaviour … when paid a fee they would heartily ring on the flower show day, at weddings, and so on, .. but never pulled for free.

Surely the noble Prince, who had then just begun an extensive eight-month tour of India, should be accorded more loyalty than this!!

More criticism came in November 1877 in a letter to the Pioneer from ‘Observer’. (China dealer Richard Riley of Bath Street?)

He was astounded that the present gang of bell-ringers were paid for basic round ringing and could not ring more complex changes, and that they had closed their ranks to new, younger recruits who might be interested in learning the art of ringing.

“There are four sets of changes that can be rung on five bells, viz. – ‘Cambridge Delight’, ‘Gog and Magog’, ‘Old Grandsire’, and ‘New Grandsire’, which would, if properly performed, be something out of the ordinary course of ringing at Ilkeston, and be better appreciated by the public”.

A yearly subscription from the public was sought at Christmas time in aid of the ringers.

This was described in the same ‘Observer’s’ letter:

“at Christmas three of (the five ringers) go round the town, calling on trades-people for subscriptions to aid them in giving the public nothing but a lot of common ringing and jingling of the bells. One of them carries pen and ink, another a cadge book, and a third a sharp penknife, what the last instrument is for I will lead your readers to judge for themselves”.

The Bells.

Published in 1879, “Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire” by J. Charles Cox has this to say about the bells and the inscriptions upon them….

The tower contains a ring of five bells :

I “Prosperity to all my benefactors, 1732,” and the bell-mark of Abraham Rudhall, of Gloucester.

II. “God save His Church, 1660,” and the bell-mark of George Oldfield.

III. “All glory bee to God on high, 1660,” and the bell-mark of George Oldfield.

IV. “Prosperity to this Parish, 1749,” and the bell-mark of Abraham Rudhall.

V. “Robert Skevington & Saml Taylor, Ch : Wardens, 1732,” and the bell-mark of Abraham Rudhall.

Time to change the ringers?

In May 1881 new rules were introduced by the Curate-in-charge at St. Mary’s.

The belfry of St. Mary’s was now to be regarded as part of the Lord’s House and thus those who served in it – the bell-ringers – were servants in the Church’s service. Henceforward they were to be young men of steady habits, regular Church attendees, and Communicants.

The Church Mutual Improvement Society was entrusted with the task of organising the group. Applications were to be sent to 25-year-old James Mitchell of 24 Chapel Street (agent for the Prudential Assurance Co.) or 18-year-old tailor Samuel Turton of 3 Bath Street.

Thus it was reported that the old ringers were summarily dismissed and ‘a fresh set of ringers’ – all members of the Church Mutual Improvement Society — installed in their place. This did not meet with everyone’s approval.

Obviously the ‘old bell-ringers’ were disgruntled, but churchwarden William Fletcher also felt this was a step too far, especially as the new bell-ringers were of dubious character – according to William. He had encountered some of them about the town, on Sunday!, at the time of Divine Service!!, obstructing the Bath Street pavement!!!

Dr. Greenfield subsequently clarified the situation. The former bell-ringers had not been suspended for not being church-goers but for arriving at the wrong time and ‘under wrong influences’!! Moreover they had not been repentant and had threatened him with the law.

In November 1881 Thursday was designated as the sole ‘practice night’ for the Church bell-ringers while Monday night was devoted to hand-bell practice.

With the approval of Dr. Greenfield, curate-in-charge at St. Mary’s, it was agreed that there would be no more begging around the parish by the bell-ringers for their benefit; in future they would be financed by a Church collection at Christmas. Henceforward cadging was unlawful and should be ‘put down’.

Applications for ringing at marriages – either for Churchmen or Nonconformists – should be made to James Mitchell or Samuel Turton. Charges were fixed and invariable.

A joyous occasion 1.

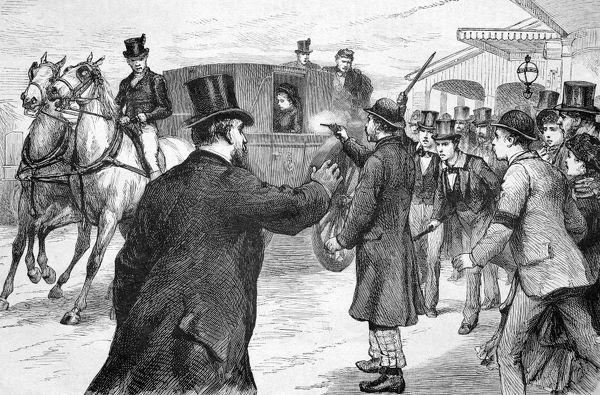

One Friday in March 1882, the Ilkeston bell-ringers rang a merry peal to celebrate Queen Victoria’s latest — and last — escape from assassination.

On the previous day Roderick MacLean, a destitute former clerk, had tried to shoot her majesty as she made her way in her carriage from Windsor Railway station to Windsor Castle. He got off his shot but was then threatened by two young Etonian schoolboys with umbrellas and apprehended by members of the onlooking crowd.

The monarch was not pleased when the would-be assassin was tried for High Treason but found not guilty on the grounds of insanity.

“If this is the law, the law must be altered”.

It soon was.

The Trial of Lunatics Act 1883 allowed a jury to return a verdict of ‘guilty but insane at the time’.

There had been several previous attacks on the Queen’s person…

in 1840, by Edward Oxford, a lonely fantasist seeking publicity, who fired twice at the young pregnant queen — and missed twice, with a brace of duelling pistols – as she rode in her open carriage. Acquitted of High Treason at his subsequent trial on the grounds of insanity, Edward spent over a quarter of a century incarcerated in Bethlem Asylum and later Broadmoor, during which time he learned to speak several foreign languages fluently, to play the violin, wrote poetry, and became a painter .. and decorator. A model inmate he was eventually released to emigrate to Melbourne, Australia where he established himself as a ‘pillar of society’.

in 1842 by cabinetmaker John Francis who tried on two successive days in May to shoot the monarch but failed…

and then a few days later, by John William Bean, who fired at the same target with a gun loaded with paper, traces of gravel, a little tobacco and pieces of a clay pipe. (a smoking gun?). Under the recently passed Treason Act John William was imprisoned for 18 months.

in 1849 by unemployed Irish labourer William Hamilton who had also loaded his pistol improperly, resulting in another failed attempt to shoot the queen as she passed by in her carriage – accompanied by three of her, by now, seven children.

in 1850 by insane ex-army officer and reclusive London dandy Robert Pate who got near enough to the Queen to whack her over the head with his cane, leaving her with bruises and a black eye.

“For a man to strike any woman is most brutal, and I, as well as everyone else, think this far worse than any attempt to shoot, which wicked as it is, is at least more comprehensible, and more courageous”. (Queen Victoria)

and in 1872 by Arthur O’Connor, a young Irish Fenian, who aimed a pistol – again, unloaded and useless – at Victoria before he was tackled and disarmed by her loyal servant John Brown.

A joyous occasion 2.

Out with the new, in with the old?

Sunday, June 25th 1882, and Alice Brown, daughter of Burr Lane lacemaker Achilles Rawdin Brown and Maria (nee Smith) is to be married at St. Mary’s Church to Chapel Street grocer Henry Uriah Bostock alias Knighton, illegitimate son of Uriah Bostock and Maria Knighton.

Elias Brown was an uncle of the bride and — more importantly!! — one of the ‘old’ bell-ringers fired by the curate over a year earlier for ‘bad conduct’. However the bride had requested that her uncle and his mates should now ring the wedding peal at her marriage ceremony.

Consequently three ‘old ringers’ turned up at the church at the allotted time only to be refused entry by the ‘new ringers’ who had the belfry key!!

Problem solved when Parish Clerk John Fish arrived, took the keys and admitted the ‘old ringers’.

Up to the belfry they went … only to realise another problem faced them. There were only three of them; five were needed to ring the wedding peal!!

By the time two further ‘old ringers’ were summoned the wedding ceremony was over, and thus a belated wedding peal was rung in the afternoon.

All this caused much unpleasant feeling between ‘old’ and ‘new’ …. and the Pioneer knew exactly who to blame!! … it was “the person who ought to exercise authority .. at the beck and call of an ignorant and minor official”.

A not so joyous occasion 3

Although now officially banned from ringing the Parish Church bells, Elias did continue his campanology. Every Christmas Day it was his custom to go around town with others handbell-ringing .. and Christmas Day of 1895 was no exception. At night he returned to the 52 Belper Street home that he was sharing with his son Thomas and family. He settled down for a couple of hours during which time the money they had gathered from the bell-ringing was shared up. At about two o’clock in the morning, taking a candle with him, Elias went upstairs to fetch some apples to share with the party downstairs. A few minutes later Thomas heard his father falling downstairs; with his wife he rushed to help and found Elias unconscious and doubled up at the bottom of the stairs, bleeding profusely from his head. The father was carried onto a sofa in the kitchen, still bleeding heavily, but never recovered consciousness. Although a doctor attended, Elias died at about 10 o’clock that morning.

Aged 70, Elias was a warp hand by trade but, living with his son for about a year, he had lately been doing odd jobs as a gardener. The stairs at the house were very awkward to navigate and for some reason Elias had left his candle behind in the bedroom when returning; son Thomas believed that he had missed his footing in the dark and fell down the full length of the stairs. He was also not carrying apples but a ‘peck of curiosity potatoes‘, and his daughter-in-law thought he might have been bringing them down as a ‘joke’.

Thomas Brown (1851-1906?), son of Elias and Sarah (from the Pam Bates Collection)

Post script: According to Parish records Elias was born on February 10th, 1825, and he died on December 26th, 1895 … at a registered aged of 68 (according to his son Thomas). He was buried in the cemetery in Stanton Road.

1899: In need of repair

By April 1899 both the bells and belfry needed attention — the bells wanted their clappers altering and the steps up to the tower were dangerously damaged. And whenever money needed to be spent on a community project like this, it first had to be raised. And this meant it was time for either a bazaar or some sort of concert.

Thus a “fairly good and certainly appreciative audience” settled down at the Town Hall on the evening of April 24th, before a platform “adorned tastefully with an array of plants” to listen to a collection of artistes, which included the town’s own Harry Stanley Hawley, the Vicar Evans and his two daughters, and the Parish Church choir.

And finally in this section, the 1882 Religious Census of Ilkeston.