From The Hollis household we walk on up Derby Road to encounter ….

The Ilkeston Colliery Company Ltd.

By the end of 1873 the Oakwell Colliery Company, ‘a small partnership affair for working the shallow coal on the estate of Lord Belper’, had taken in a large number of shareholders, thus forming a ‘strong and influential‘ Limited Liability Company (the latter being a business vehicle for attracting extra investment capital without the investors incurring huge risks). With this extra financial investment the Company had brought powerful machinery into the Derby Road site, to work the Kilburn seam there.

In 1874 the Ilkeston Colliery Company was formed from the Oakwell Colliery Company and further developed the Oakwell Colliery site, opposite to the house of Kester Harrison – as was !

At the end of February 1874 the Belper pit and a new Oakwell pit were opened on the land of Lord Belper when his lordship’s youngest son turned the first sod.

“The ceremony of ‘christening’ in champagne, which followed, resulted in the naming of the two main shafts ‘Belper pit’, after the owner of the estate, and ‘Oakwell pit’, after a spring of excellent water of much local celebrity and which gives its name to the farm on which it is situated. … The sinkers have since commenced work, and are now in active operation. The shafts will be 250 yards deep, at which depth it is expected to reach the celebrated Kilburn seam. It is estimated that it will take two years to complete the sinking. In the mean time a shallower seam is being worked. This is the only colliery in the locality, it is believed, whose proprietors are liberal in politics, a circumstance not without future significance”. (IT Feb 28th 1874)

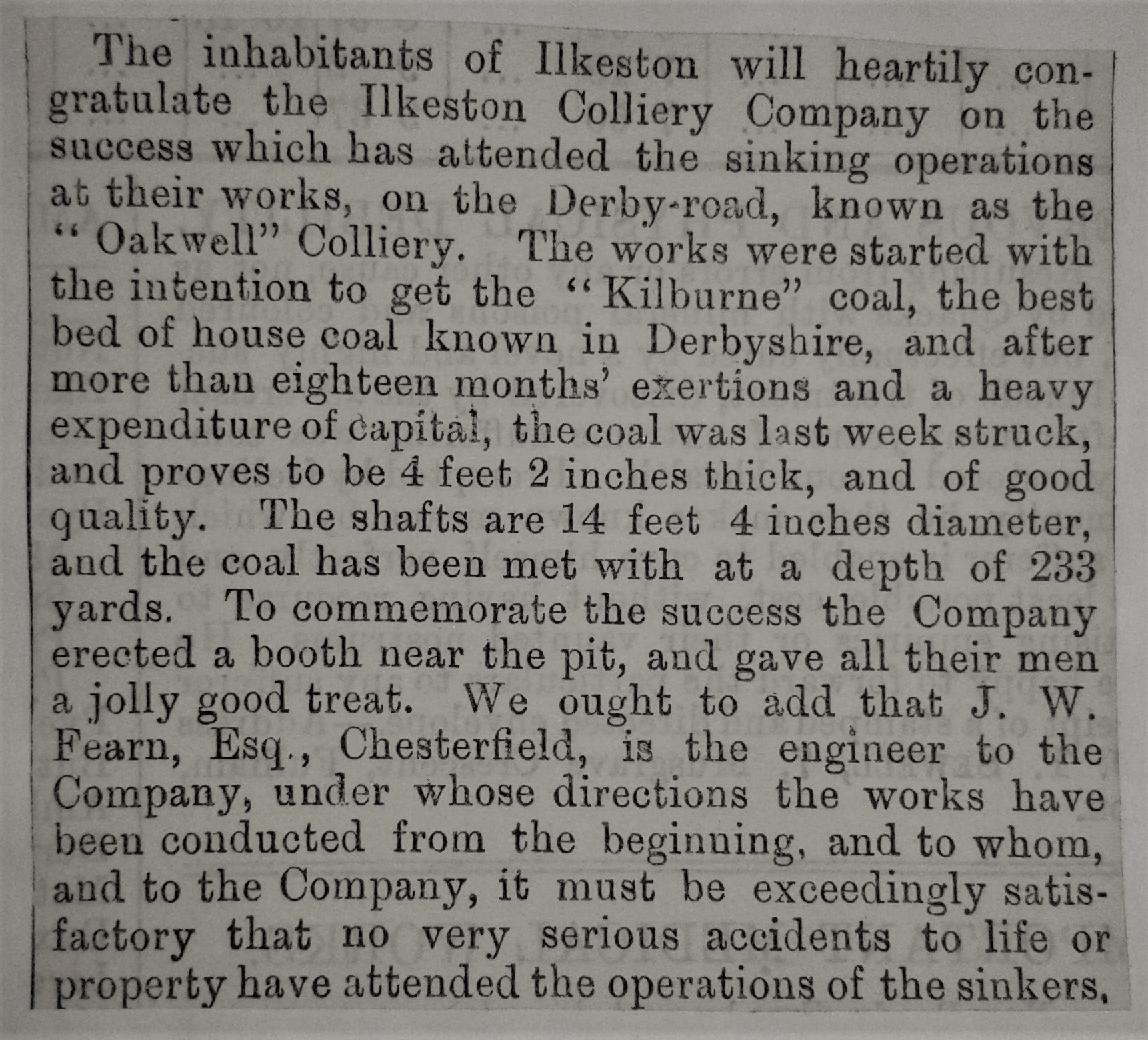

The Ilkeston Pioneer August 12th 1875

The proprietors were William Sudbury, Harry Bostock, George Swanwick and William Hewitt.

On January 19th 1876 the second shaft of the Colliery reached Kilburn Coal at a depth of 231 yards. During the process not a single man was injured. The shafts were 14 feet 4 inches in diameter and bricked at the rate of eight yards a week.

In 1878 William Sudbury was the managing director of the Ilkeston Colliery Company

The 1885 Ilkeston Coal Strike

At the beginning of July 1885 the workers at Oakwell Colliery, men and boys, received 14 days’ notice to leave their employment, at the end of which period they would have their wages reduced and recommence their employment. The cause of this action by the employers was the severe downturn in the coal trade. The day before this notice was put into effect a number of the boys marched up South Street in a procession, with the notice papers pinned to the front of their hats.

Within the 14-day period the colliers met at the Durham Ox, together with workers of the Manners and Cossall Collieries, and decided that the proposed reduction to their wages was too great — they would resist any reduction greater than 10% and they duly came out on strike. It was estimated that about 1200 colliers were affected.

At the beginning of the following month, after the men had been on strike about three weeks, it was rumoured that some ‘blacklegs’ had returned to work at Cossall. An irate crowd, numbering around 1000 persons (or 2000 depending upon which newspaper you were reading), gatherered at the pit and when its members discovered that the ‘scabs’ had already left work, they made for the home of one of them — Frank Newton in Station Road. It was reported that Frank had organised the returning labour and was responsible for contracting their hiring. Hence he became the obvious target. Every window was broken and slabs of rock thrown into his house while the family cowered in the cellar. By the evening the crowd had moved on to the home of the pit manager in Chaucer Street, where shots were fired and nine people injured. James Holding, the manager, lost several doors and windows, his greenhouse and vines within, a garden roller, a pig and a number of fowls, and a boundary wall. Eventually a police posse arrived from Nottingham to reinforce the Ilkeston constabulary, and at around midnight order was restored. (It should be noted here that at a later court hearing, both Frank and James received compensation for the damage done to their property … to be paid by the ratepayers !!)

Within a day, 16 ‘ringleaders‘ of the riot were arrested in a midnight and secret police raid — all except one were Ilkeston colliers. Further arrests followed but it was felt by the arresting officers that the ringleaders of the riot had not yet been caught. Thus when the prisoners appeared in a later court — several of them young lads — they were bound over to appear at a later hearing if they were needed. A couple of lads were however sentenced to three weeks’ detention, with hard labour, in the House of Correction.

Meanwhile fruitless negotiations had taken place between the pit owners and the strikers, the latter now seriously feeling the effects of being out of work and unpaid for several weeks. They and their families had received free soup from Joseph Beardsley of the Flower Pot Inn in Chapel Street, and Edwin Sutton, clothier of Bath Street, had provided a hot breakfast for 60 children each morning in one week. And there were other acts of local kindness to alleviate the hardship.

At the end of August, a settlement was reached between the miners and the owners of the Oakwell and Manners Collieries — the wages would be reduced but only by half of what had originally been proposed. No such agreement was made at the Cossall Colliery however, until three days later when the miners agreed to resume work on the same terms. But it was not to be …. the miners at that colliery refused to return when it was learned that some men, accused in the original rioting, would not be allowed into the pit by the owners until they had proved their innocence at their future trial.

That trial occurred at Leicester Assizes on November 2nd (Leicester being the nearest place with ‘suitable’ accommodation for the hearing).

The list of accused: George Severn, Thomas Wheatley 16, Albert Wright 18, Samuel Straw 19, William Adams 20, Joseph Baker 40, Thomas Quinn 37, Matthew Bostock 18, Samuel Fretwell, Albert Campbell 28, Samuel Thorpe 22, William Howe 17, John Martin 23, Joseph Spowage 22, Herbert Tatham 17, Samuel Bostock 20, Joseph Severn 21 …. all colliers.

Richard Noon, Elizabeth Webb, Allen Harrison, John Bostock, Isaac Leadbetter, William Woodward, Edward Endsor, Charles Bonner, Keziah Stevenson, Amos Sisson and Grace Baker.

“That they, being riotously and tumultously assembled together, with divers other persons, to the disturbance of the public peace, did, with force, damage and injure a certain house, the property of Geo. Barker, at Ilkeston, on August 5th” (the property in the indictment was the premises in Station Road, where Frank Newton was the tenant).

Most of the accused pleaded guilty but as they had returned to work the prosecution did not press charges, and they were bound over in the sum of £10, to come up for judgement when required. Against those who pleaded not guilty, no evidence was presented against them and they were discharged.

This was not a good time for the Oakwell Colliery.

On September 18th 1885, because of the negligence of two enginemen, the ascending cage smashed the iron ropes, causing the cage to fall, demolish the engine-shed and damage the winding-gear. Fortunately no-one was hurt although 300 men were, for some time, trapped in the pit and had to be brought out with a rope and bucket.

Just over a week later collier James Wheatley was killed when he was crushed as he was maneuvering an empty tramcar down the mine. The tramcar tipped over, crushed James, broke his neck and killed him instantly. “Deceased leaves a wife and several children” (NG) Three children were left without a father and by December it was four children when James’s widow, Elizabeth Sarah (nee Thompson), gave birth to Charles Wheatley on December 12th, 1885. Three years later the children were also without a mother and were living with their maternal grandmother.

And then in March 1886 another fatality occurred when John James Goddard, a banksman, was crushed between two trucks while shunting them. He was taken to the Cottage Hospital “where he lingered for several hours”.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

By the later 1870’s there was a row of houses between the Ilkeston Colliery premises and Belper Street. Adeline introduces to some of its inhabitants.

Thomas Potter.

we now meet “Thomas Potter, warper at Carriers, who lived in the first one of the row of houses”.

Born in 1829 Thomas Potter was one of the dozen children of William and Sarah (nee Rice) (See Frank Hallam’s Row).

On the 1861 census he appears as a lace warper in Moors Bridge Lane.

In June 1854 he had married Jane, the daughter of coalminer Benjamin Rigley and Mary (nee Tomlinson), also of Moors Bridge Lane, and from that time and at regular intervals until her death, aged 37, in December 1872, Jane gave birth to a total of 11 children.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

Nahum Ironmonger. (1839-1920)

“Mr Ironmonger, shoemaker, was in another”.

In 1871 this was 15 Derby Road.

Boot and shoemaker Nahum Hargraves was born in Castle Donington on August 11th, 1839, the illegitimate child of Mary Hargreaves, who married lacemaker Thomas Ironmonger a short time after her son’s birth. Thomas was possibly Nahum’s natural father and the child was given the Ironmonger name after the marriage.

The family continued to live and grow in Castle Donington until they all eventually came to Ilkeston about 1854. In that year and in this town Nahum was baptised (June 4th) with his five siblings, all with the Ironmongder family name.

Later children William and Harriet Ironmonger were born in Ilkeston.

After the arrival here, the family lived in Brussels Terrace for a period before settling in Park Road.

Nahum later left to work in Derby where in 1860 he married Sarah Smith, daughter of labourer John and Elizabeth, and continued to live there before returning to Ilkeston at the end of the decade with his wife and three children.

They lived at 15 Derby Road and then in the later 1880’s moved into South Street where Nahum had had a shop for several years.

Sarah Ironmonger died in South Street on January 8th, 1909, aged 71.

Betsy Ironmonger (1850-1898)

Almost a year after the death in infancy of her illegitimate daughter Annie Maria, Nahum’s younger sister Betsy married miner Samuel Grebby in March 1877, a union which very soon proved to be unhappy — at least for Betsy.

After the marriage the couple lived with Samuel’s parents, Henry and Rebecca Charlotte (nee Stevens) at Little Hallam and frequently quarrelled. Betsy claimed that her husband had, on occasions, struck her and at one time broken two of her teeth.

In July 1879 the arguments resulted in her mother-in-law ordering Betsy out of the house and having failed to be granted a place at the Basford Workhouse she was later forced to return to the hostile environment of the Grebby family home.

What could she now do?

Early Victorian divorces usually required application to Parliament for a private act, an expensive process beyond the means of most ordinary people — before 1857 only four women had achieved divorce in this way. However the 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act for the first time allowed secular divorce in a new civil Court for Divorce and Matrimonial Causes and enhanced the rights of women in marriage and divorce.

A divorced or legally separated woman could now be awarded maintenance and be granted the property rights of a single woman so that she could bequeath or inherit her own property. Also if a man deserted his wife he now had no claim to her earnings. However whereas a man only had to prove his wife’s adultery, a woman had to prove that her husband had committed an adultery but also that it had been aggravated by incest, bigamy, cruelty or desertion. And the process was still very expensive such that there were only about 150 divorces each year within the next ten years.

An 1878 amendment to the 1857 Act allowed local magistrates to grant a woman an order for separation on the grounds of her husband’s cruelty, and to allow her to claim maintenance and custody of any children.

When Betsy was further assaulted by Samuel, this new 1878 law allowed her to raise the issue of separation and maintenance at Ilkeston Petty Sessions. Although Samuel was fined for his behaviour, the couple did stay together living in the Little Hallam area, away from Betsy’s in-laws and increasing the size of their family.

Their last child was born in 1889 before Samuel died at Little Hallam in February 1891, aged 37.

Her husband’s death however did not release Betsy from her physical beatings. It seems that her eldest son, Harry, now adopted the role of his deceased father and Betsy was forced to take him to court in February 1895. Aged 17, Harry was averse to getting out of bed in the morning and going to work. When his mother remonstrated with him he would use his fists to retaliate. Betsy was a forgiving woman however and defended her son — he had fallen from a scaffold at Stanton Ironworks the previous June and had not quite been himself since. The magistrates adjoined his sentence to see if his conduct towards his mother improved.

It didn’t. The couple were back at the Petty Sessions a month later. A breakfast-time argument over a piece of cheese had led to Harry strike his mother. Although he got the cheese he also got a month in jail with hard labour. Betsy was living in such poverty that her costs for the complaint were remitted.

Betsy died at 11 Little Hallam on January 25th, 1898, aged 47.

P.S. Interestingly (?) Samuel Grebby was born on November 6th 1853, almost at the same time as his eldest brother, John Grebby alias Stevens, was registering the birth of his first child.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

William Tunnicliffe, Parish Clerk (1778-1843) or house painter (1807-1875) ?

“Then came old Tunnicliffe’s cottage” which, from 1871, was 13 Derby Road.

Framework knitter William Tunnicliffe senior was Parish Clerk from 1809 until 1842, the year before his death, when he was living in “Moors Bridge Lane”, the earlier name for Derby Road.

In her letters, Adeline describes an incident before her birth (in 1854), involving ‘old Tunniclffe‘ and the then curate at St. Marys, Richard Moxon (who died in 1836)

“One Sunday the Rev. Richard Moxon was preaching in the old Parish Church of St. Mary, his subject being Moses speaking to the children of Israel.

On reaching his peroration he called out, ‘And what did Moses say?’

Old Tunnicliffe had evidently been asleep, for he started up, and said ‘Hey sez they’ll be no moor candles till tothers ur peed fur.’”

(The startled William was thinking that Richard was referring to Moses Mason chandler of Bath Street)

‘Progress’, a writer for the Ilkeston Pioneer in April 1853, recalls the same ‘old Tunnicliffe’ ….

‘…. with his audible voice, that could be distinctly heard all over the church, repeating the responses, and we boys, who were to read aloud along with him. Sometimes we got on too fast, and had done long before him; at other times we were all behind, which was the worst part of the business, as the minister had to begin before we had finished. Sometimes there were half a dozen voices to accompany the clerk; at other times only one, or none at all. I am afraid we were a sad lot, after all the pains taken with us, paying more attention to who was “asked” in Church than anything else’.

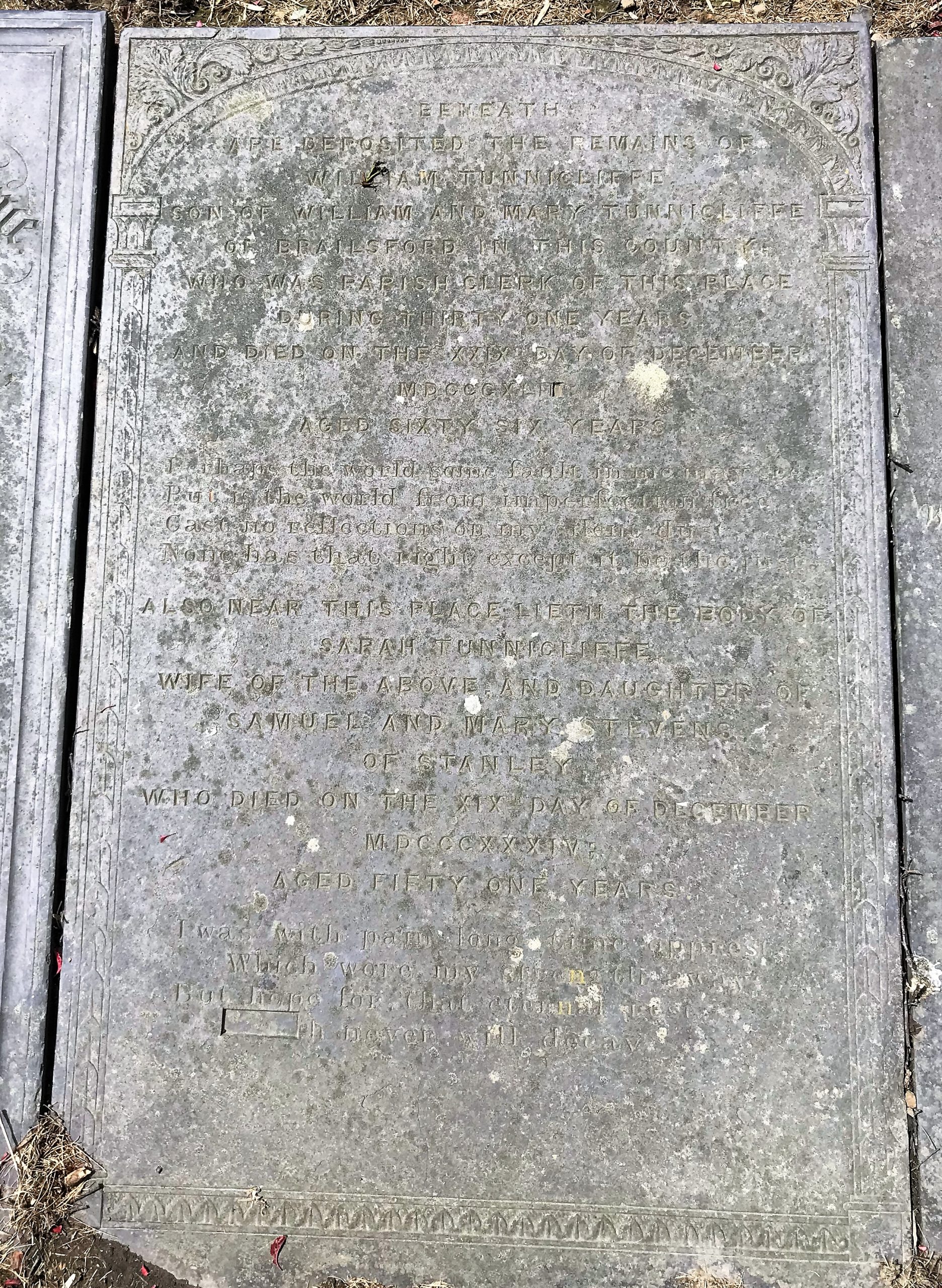

William senior, the Parish Clerk, has a very interesting gravestone (below) which can be found, lying flat, in the south section of the churchyard. The first part of the inscription is about his own life and you may find it difficult to read … so there is a transcription beneath.

BENEATH ARE DEPOSITED THE REMAINS OF WILLIAM TUNNICLIFFE, SON OF WILLIAM AND MARY TUNNICLIFFE OF BRAILSFORD IN THIS COUNTY, WHO WAS PARISH CLERK OF THIS PLACE DURING THIRTY ONE YEARS AND DIED ON THE XXIXTH DAY OF DECEMBER MDCCCXLIII AGED SIXTY SIX YEARS

Perhaps the world some fault in me may see

But is the world from imperfection free

Cast no reflections on my silent dust

None has that right except it be the just.

William’s parents were Willaim and Mary (nee Holmes?), married at Brailsford on March 20th 1778, and their child William was baptised there on August 16th of that year. Looking closely at the marker, you might detect a mistake (?) made by the stone mason, perhaps unsure of the year of William’s death … it was 1843.

The inscription continues with details of William’s wife.

ALSO NEAR THIS PLACE LIETH THE BODY OF SARAH TUNNICLIFFE, WIFE OF THE ABOVE, AND DAUGHTER OF SAMUEL AND MARY STEVENS OF STANLEY WHO DIED ON THE XIXTH DAY OF DECEMBER MDCCCXXXIV; AGED FIFTY ONE YEARS.

I was with pain long time opprest

Which wore my strength away

But hope for that eternal rest

Which never will decay.

You might notice another error (?) on the last line of the slate, again corrected by the mason. Parish records also indicate that Sarah was buried at the church on December 18th, 1843 … a day before her death !!

Adeline’s letters could be referring to ‘Tunnicliffe senior‘ though obviously not from personal experience … he would have been known to her father John who may well have spoken of his own recollections to her. Alternatively she could be writing of his son, house painter William junior, who also lived in Moors Bridge Lane, later Derby Road, during the latter part of his life but died in Pedley Street at the home of his sister Rebecca in November 1875.

Born in 1807 William junior married Mary Rogers in September 1832 and had at least five children before Mary died in July 1843.

At this time the family was living in South Street and William’s subsequent liaison with Mary Hackett Daykin Toplis, also of South Street, resulted in the illegitimate birth of Arthur Toplis in June 1851. The eldest child of South Street basket maker George Toplis and Ann (nee Daykin), Mary had given birth to at least three more illegitimate children before Arthur. (See Burgin’s Yard and Row)

Just over a year after William junior’s death, his younger brother Joseph Tunnicliffe went missing. He had worked as a brickmaker at the Gallows Inn brickyard but had recently moved to live near Nottingham, working as a stationary engine driver.

A fortnight before Christmas Joseph was drinking at the White Cow beerhouse in Nottingham Road one foggy Thursday evening and rather worse for liquor, he started to walk back to Nottingham along the path of the Great Northern Canal, via Trowell and Wollaton. He never made it home.

By Sunday worried relatives were searching for him and found his hat and walking stick at the side of the Erewash River at Gallows Inn. The waterway was dragged by the police but no sign of Joseph. It was feared that recent flooding there might have washed a body several miles distant.

After three weeks there was still no sign of the brickmaker. Local people were certain that Joseph was not the sort of man to miss his way and walk into the river, in which case his hat and stick would have accompanied him.

Foul play was strongly suspected – some people were certain that Joseph had been brutally murdered and his body disposed of. The hat and the stick had been placed by the river to set a false trail for the police. Rumours circulated that he had in his possession several pounds of gold and silver which he had openly displayed in the public house before setting off home and which provided an obvious motive for his murder. It was said that Joseph had been seen mysteriously to enter a house at Gallows Inn and never come out again! The inmates of said house left the house on the night of his disappearance.

About a month after the disappearance dragging operations were renewed, this time with the help of a hired boat.

A short distance from the bridge over the Erewash at Gallows Inn and 100 yards from where his hat and stick were discovered the body of Joseph was hauled from the river, together with his watch and chain, 14s 6d in a leather purse and 7½d loose change, tobacco, two pipes, a pocket knife and a few other personal articles. There were no signs of violence upon the body and the jury at the subsequent inquest returned a verdict of ‘Found drowned’.

The ‘Ilkeston Mystery’ was unravelled.

Another younger brother of William was James Tunnicliffe, born in 1810, who married Sarah Brmaley on May 12th, 1831. Ten years kater the couple were still living in Moors Bridge Lane, now with their four children. It was at this point that James found himself in Derby County Jail and Hoyuse of Correction for three months, with hard labour, for neglecting his family.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

Traffic warning. 4pm. March 18th 1875.

William Bentley, landlord of the Black Horse Inn at Mapperley, with passenger John Fowkes, landlord of the New Inn at Horsley Woodhouse, was speeding home down Derby Road in his gig. As it passed the works of the Ilkeston Colliery Company a wheel caught that of a passing cart, heavily laden with bricks belonging to Manor House builder Frederick Shaw. A shaft of the gig snapped, the horse bolted, the two landlords were tossed out, the gig overturned, the other shaft snapped, the vehicle was wrecked and the horse disappeared into the distance.

A few nearby colliery labourers rushed to assist and found William with several bleeding wounds to his face and an injured arm, while John’s left leg was rendered useless and his hip was broken or dislocated.

Getting John home proved to be difficult. At first, a colliery cart, lined with straw, was used as transport but its jolting was too much for him to bear.

Then onto the scene came Mr. Harvey of West Hallam with his light spring cart which proved more comfortable for the invalid and John was conveyed home.

The bolting horse was eventually stopped at High-lane in West Hallam.

——————————————————————————————————————————————-

Let us pause to gaze upon Oakwell Farm.