This section amalgamates the parts of several other sections, in an attempt to provide a more comprehensive story of Ilkeston’s struggle with its sewage problems during the Victorian period.

Personal hygiene or the lack thereof

In 1853, the Ilkeston Pioneer newspaper reported on an inspection of the town organised by the Sanitary Committee, its purpose to root out everything that was ‘foul and offensive’ in the town. One of the appointed inspectors later described a visit which he had made to a house in Moors-bridge Lane (Derby Road). He politely knocked at the door but as no-one answered he felt able to enter the house. The first room was empty but in the parlour he found a pair of donkeys ‘quietly browsing in the corner, safely sheltered from the pitiless storm and plentifully supplied with fodder by their humane owner!’. In the same area he also discovered that “another resident always kept ‘the fatted calf’ in his bedroom, but could not tell whether the poor innocent was what is considered good company for a bedroom”.

A couple of months later and the same newspaper was not very impressed with the ‘work’ of this newly-formed Sanitary Committee … where are the Scavengers, appointed to clear up the streets ?? ‘Nowhere to be seen !!‘ was the answer. And what about the ankle-deep soft sludge which ‘decorates’ the boots of anyone who dares walk through the town … why, it is still where it always was, lying undisturbed in the public streets !!

The newspaper continued its campaign to improve the town’s sanitation and in an editorial of 1861 it again took stock of the housing of Ilkeston’s labouring poor which it now described as the “monster evil of our times”…..three, four or more families in one house; often one family per room; parents, grown-up children and a ‘lodger’ perhaps sleep in the same area; “no provision for the ordinary decencies of life”. Disease and immorality were all around the folk of Ilkeston. As the nation grew, as industry flourished, as the population expanded, the problem worsened and the Pioneer saw no quick solution. It did however call upon landlords to provide decent homes with “adequate provision for the moralities of life”.

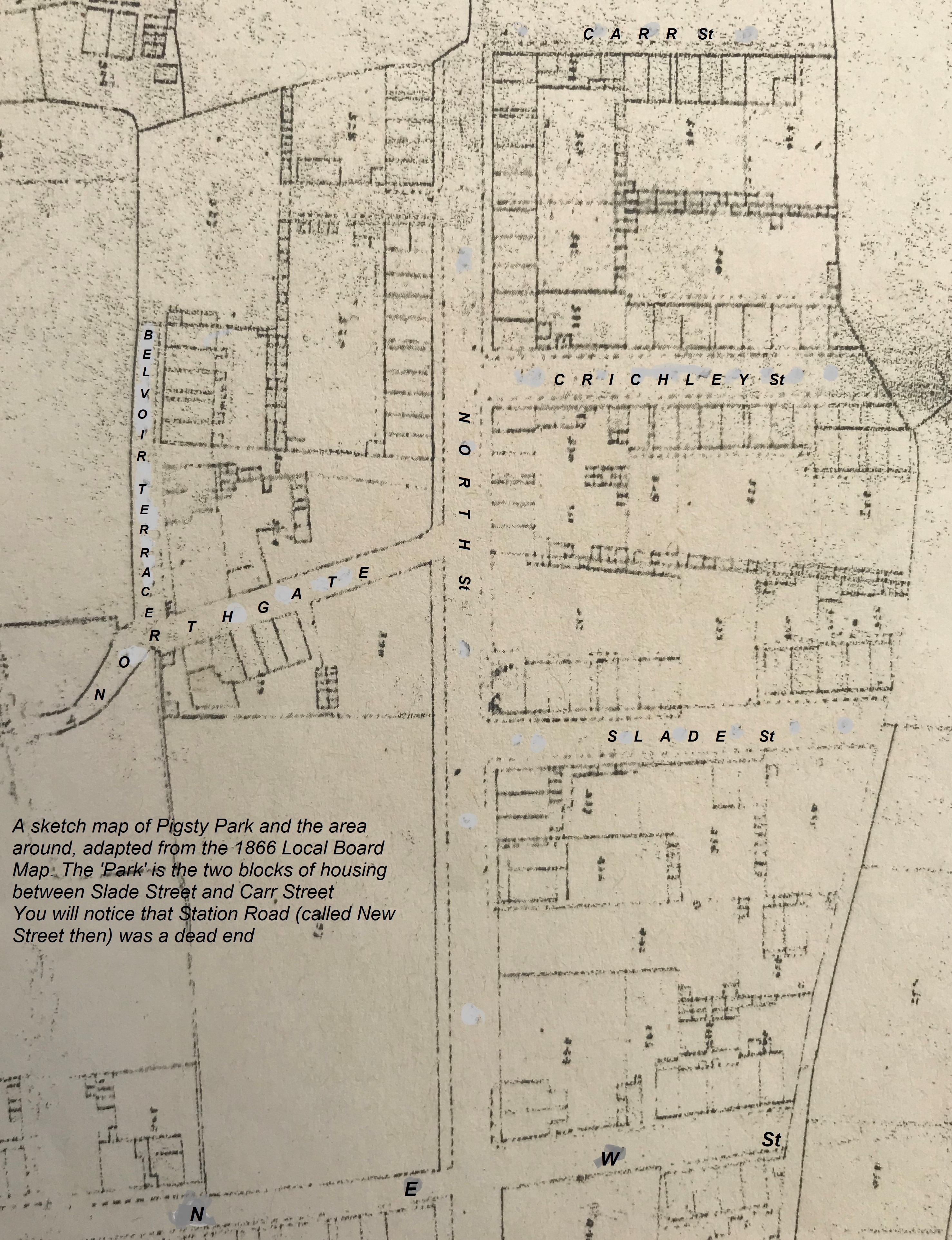

Perhaps we could look at an area down Station Road, its houses and its landlords, as an example of what the Pioneer was complaining about.

Pigsty Park was the district, about an acre and a half in area. The name seems to have originated about 1860, when it featured in the Ilkeston Pioneer of that time.

It included part of North Street, Crichley (or Critchley) Street and Carr Street, which Adeline Wells described as “not very attractive, in fact the road was so bad that one member of the Local Board said that the area was worse than a pigsty. The name caught on, and for many years that part of the town was called ‘Pigsty Park.’”

The district is listed by that name in the 1861 census, one of its residents being Thomas Shaw, builder and Primitive Methodist preacher, who designed and erected several houses in the area, on land he had purchased from Joseph Bailey, lace manufacturer for £700 in the early 1860s.

The homes were built in about six months around streets made of iron stone cinders. Typically they had four to six well-lighted rooms described as 10 feet by 11 feet, some larger, with height eight feet to 10 feet, each with a garden of 60 to 70 square yards and with a ‘necessary’ at the end of each, with a few exceptions.

There were ‘panty-pits’ or small cesspools, one for every two or three houses, at the rear of the properties, to ‘take the swilling and washing away from the doors’ and which drained out to an old town water course. These pits were generally kept well apart from the property water sources.

About a dozen soft water cisterns were erected in the area, supplying washing water, while a well, 15 yards deep was sunk to supply hard water. There were three main drains with pipes from each property leading to them, while surface rain water was carried away efficiently by the drainage provided.

The houses were let at 2s 7d per week and had been popular although as the articles in the Pioneer surfaced, criticising them, townsfolk were less enthusiastic about them.

Adeline remarked on the deficiencies of this sanitation system. “The drainage of the town was a very primitive affair. True, there were grates in the streets, but as there was no carrying water, anyone going through the streets after the midday meal, especially on Sunday was assailed by the unpleasant smell of cabbage water, etc. But people were glad to have this way of drainage, inefficient as it was, rather than the old cesspools.”

Time moved on but without significant improvement it seems. In 1868 the Board had borrowed £2500 to lay down sewers in the town, though there was no investment in sewage disposal at that time.

The Buchanan Report of 1870

In 1870, in connection with a fatal epidemic of scarlatina which in the previous year had caused 81 deaths, and the prevalence of enteric (typhoid) fever in the town, the inspector for the Medical Department of the Privy Council George Buchanan conducted an investigation and produced a report on the Sanitary Condition of Ilkeston.

He discovered that ‘excremental pollution’ was widely diffused in the water of the town and cited ‘ill-kept roads and unclean channels’, overflowing ashpits with filthy refuse, and pig-styes far too close to cottages. The report exposed serious flaws in the town’s sewers and the disposal of night-soil — flaws which needed addressing perhaps with a new sewerage system ? (Night soil was the combined contents of ashpits and privey middens).

In my not small experience of stinks, I have never met any to surpass the privies and ash-pits of Ilkeston. There are no public arrangements for attending to the same….

There is a certain sort of drainage in the town, by brick and pipe drains … but open brooks and ditches carry pollution to the Erewash Brook and Canal …..

Thus it appears that in air and water there is in Ilkeston widely diffused pollution and there is no-one with the function of an Officer of Health. The Local Board has one officer who combines in half his person the function of Surveyor, Inspector of Nuisances, and Rate Collector. He has 2500 collections to make in 156 days. Of systematic inspection, there is absolutely no trace whatever.

After this scathing assessment, Ilkeston’s Local Board did try to respond and put Buchanan’s recommendations into effect.

In 1872 the Board approached the Duke of Rutland (via his agent Robert Nesfield), asking for the use of farmer Robert Noon’s clay-hole at Gallow’s Inn — Robert being a tenant of the Duke. The site was needed to ‘store’ night-soil. The agent initially refused the request, especially as he wasn’t sure where this site was. This followed a similar refusal from Messrs. Potter for the use of land at the top of Grass Lane (Norman Street), and for the use of an old brickworks on Awsworth Road. The Board was trying !! But so far, the only night-soil depot was down Derby Road, on a piece of land belonging to the Attenborough family.

Some effort was made to improve the system of drainage too. For example, in the Spring of 1873 the Local Board Surveyor was asked to prepare plans for an improved drainage in the North Street area of Pigstye Park though an illness to Thomas Shaw, one of the principal property owners in the area, thwarted immediate action and problems continued therefore.

However no households were isolated to prevent disease contagion, drainage was still very imperfect, and inhabitants continued to throw stinking refuse into open channels and streets (according to the Pioneer’s letters column whose mysterious contributors were always eager to have a go at the Board !!). And as the danger of smallpox continued, officers of the Local Board went to inspect a covered cart, belonging to draper Charles Woolliscroft, to ascertain if it might be converted and used as a temporary hearse, or to convey patients to the Basford workhouse. Perhaps some more far-sighted action was needed ?

In 1874 the parsimonious Local Board announced the ‘discontinuation of free removal of night soil’. It would no longer organise the emptying of privies, privy cisterns, ashes pits, etc. gratuitously as heretofore. Householders could now do this independently or apply to the Inspector of Nuisances who would organise removal for a fee. Perhaps this is what led one resident of Lee’s Yard (or Albion Place) to take matters into his/her own hands at the beginning of 1875. That resident emptied the contents of a cistern into the street, contents which had been allowed to fester there for several weeks !! The furious Pioneer was quickly ‘on the case‘ of course…. “a stinking unsightly mess of night-soil — the ground all around saturated with its reeking contents. The filthy state of that yard … is a disgrace to the Local Board…. a pity that we have not got a Government Inspector from the London Board .. to prosecute the Local Board for neglect”.

However the town would have to wait a few years for one such Government Inspector to arrive, though arrive he did … eventually !!

In 1874, when investigating the future sewage disposal requirements of the town, the Local Board found that raw sewage from houses in the Station Road area was flowing out of pipes into an open ditch and thence to the river Erewash. There was a considerable amount of solid matter and the outfall had discoloured the water, making it thick and nasty and creating an offensive smell…. well beyond this area.

The Local Board starts to extract its finger

By 1878 the Ilkeston Local Board had decided that it would need to acquire about 60 acres of land on the south side of the town for a sewage farm near Hallam Fields. This would entail compulsory purchase of land from some ‘unwilling’ tenants of sections of that land, which in turn meant that approval from the Local Government Board would be needed … which in turn meant that an inquiry would need to be held !! The projected land purchase would require a Government Loan … and this again would require Local Government Board approval.

By June 1880 the Local Board had been discussing a new sewage scheme for the town for some time. Plans for a sewerage scheme had been prepared by Benjamin Shaw Brundell, a civil engineer of Doncaster some years previously. However these plans had been shelved and the scheme wasn’t pursued. Sadly it seems that someone forgot to pay Benjamin’s fee of £169 for his time and trouble. The Board which considered that it was far too much for the work he had done, had equivocated and the matter dragged on.

Now however the Board had come up with an alternative plan drawn up by its own surveyor and had (almost) come to a firm conclusion. This plan was in two parts and the surveyor to the Board George Haslam had in his possession a ground plan of the scheme which was to dispose of the town’s sewage by irrigation. Plans had been made to buy 72 acres of land at Hallam Fields for a sewage farm.

Part 1 of the plan concerned a large main sewer of about 2000 yards in length, costing £500, which had just been constructed, intercepting the sewers of Derby Road, Belper Street, Union Road, Albert Street and adjacent streets, taking their sewage to this farm. Part 2 was the larger and more costly part and hadn’t been started yet. It would require “much more consideration” and would take the total cost beyond £10,000, necessitating a very substantial loan from the Government. Another public enquiry would be needed for the loan to be sanctioned.

In November 1880 a(nother) Local Government Inquiry was held at the Town Hall, this time to consider the Local Board’s application for a loan of £12,000 for sewerage works, and an additional loan of £2000 for improvements to the water supply. At that time the Pioneer included a helpful résumé of events so far.

- various sewage disposal schemes had been put forward in recent years.

- plans by Mr. Brundell, civil engineer of Doncaster, for yet another scheme, were recently prepared but set aside.

- the Local Board’s surveyor George Haslam had then prepared specifications for a sewage works at Little Hallam.

- land had been compulsorily purchased to accommodate the works.

- since the last Board elections in April the newly elected members called for a reconsideration of the surveyor’s scheme.

- the Erewash Canal Company has called upon the Local Board to cease the influx of sewage into its canal and asked the Board to pay for the cleaning of the canal between Barker’s Bridge and Babbington Wharf.

As a result of the Inquiry the Local Board was given permission to obtain a loan to carry out this sewage scheme.

The Blaxall Report of 1881

In 1881 the then inspector for the Local Government Board, Dr. Francis Henry Blaxall, arrived in Ilkeston to produce another report on the town’s sanitation system. In his final summary he noted that since the previous report Ilkeston’s Local Board had “not been altogether unmindful of the duties imposed upon (it) by the Legislature. At the same time, through the want of sustained effort on its part the measures undertaken have not fulfilled the desired end, while there has been a total want of remedial action in respect of certain conditions which exercise a very prejudicial effect upon the public health”. It went on to identify many weaknesses in the sanitary conditions and health environment of Ilkeston, but one of the improvements it noted was the development of a new sewerage system. So at the end of November 1882 the Local Board appointed Benjamin Shaw Brundell (once more !!) as the engineer to carry out its sewerage scheme. In July 1883, after tenders had been received, Benjamin recommended that William Cunliffe’s offer to construct the system’s infrastructure be accepted — Benjamin knew that William could be relied upon to do a good job !! (William’s offer was for £4580 and was the lowest).

Blaxall’s report added detail describing what the Local Board’s plan intended; “It is satisfactory to report that the (Board), after long opposition on the part of some of its members, (will) provide intercepting sewers, which, after collecting the contents of the various sewers, shall convey the sewage to land, there to be disposed of by infiltration” and it noted the urgent necessity for the work to be carried out without delay. In the meantime “the sewerage continues to be very imperfect and defective, and all the sewage finds its way … into the river or canal. There is no provision for the ventilation or flushing of the sewers. The heads of them are closed and the street gullies trapped, while the outlets are left open, allowing the air to blow freely up the sewers…..”

Sewerage recommendations from the Blaxall Report

The necessity of adopting an improved system of privy accommodation by the adoption of the dry earth or water carriage principle.

The systemic removal at short intervals of refuse and manure from the vicinity of houses.

The ventilation of all sewers and drains, the proper trapping of drains in the vicinity of houses, and the prevention of direct communication between indoor sinks and waste-water pipes and the sewers and drains.

Sewage should be no longer permitted to flow into and pollute the river and canal.

The completion of the proposed sewerage works, with means of flushing the sewers.

A sewerage system at last

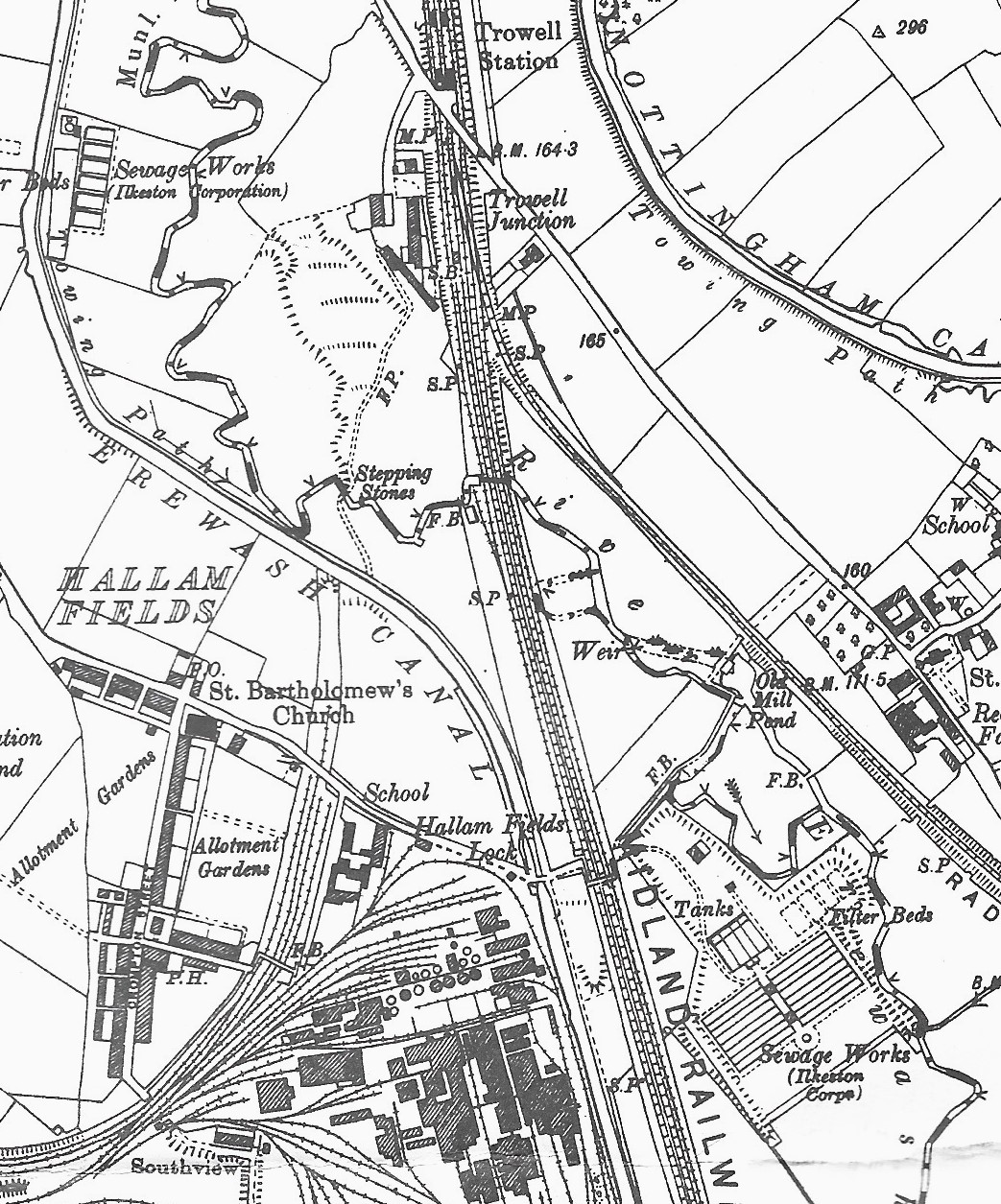

April 10th, 1884 saw the formal opening of the sewage farm when the members of the Local Board made an official inspection of the newly completed ‘sewage works’ for the town — engineered by Benjamin Shaw Brundell and built by William Cunliffe at a total cost of over £10,000 … an inspection which started close to the Ebenezer Chapel in Awsworth Road. The guided tour did not, of course, include much of the town’s scenic beauty, though it culminated at the new sewage farm, extending over six acres with 30 filter beds. Let’s follow this guided tour …

Mr Brundell said that there were two sewers in that Awsworth Road locality not yet connected with the scheme, as the surface water got into them, and it was desirable to keep all such water ot of the sewage. The large flushing tank on the east side of Ebenezer-street was then visited, and the party waited until the large syphon, which is placed in the collecting tank, operated. The tank is computed to hold 5000 gallons of sewage and receives all the sewage from Cotmanhay. The sewage collects in the tank until it is full, when the syphon acts, and allows the sewage to rush off with considerable velocity in order to flush the sewers in the vicinity and keep them clear. (the sewage from the tank being forced in the direction of the sewage farm)

Mr. Brundell said that it would be a good plan for the Board to employ a man to count the number of times this tank discharged during the day. They would gain valuable information as to the amount of sewage they had to deal with from the Cotmanhay district.

The party then visited a ‘catch pit’ in Awsworth-road, at the bottom of which the sewage could be seen trickling along in a sluggish stream. The principle of these pits, for there are several in the scheme, is that the ordinary sewage passes through them into the main sewer; when, however, the volume of sewage is swollen by heavy rains, a floating weight connected with the door shuts off communication with the main sewer, and turns the stream water down another channel into the Erewash. Were it not for this arrangement the sewage farm would speedily be flooded out, and ruined.

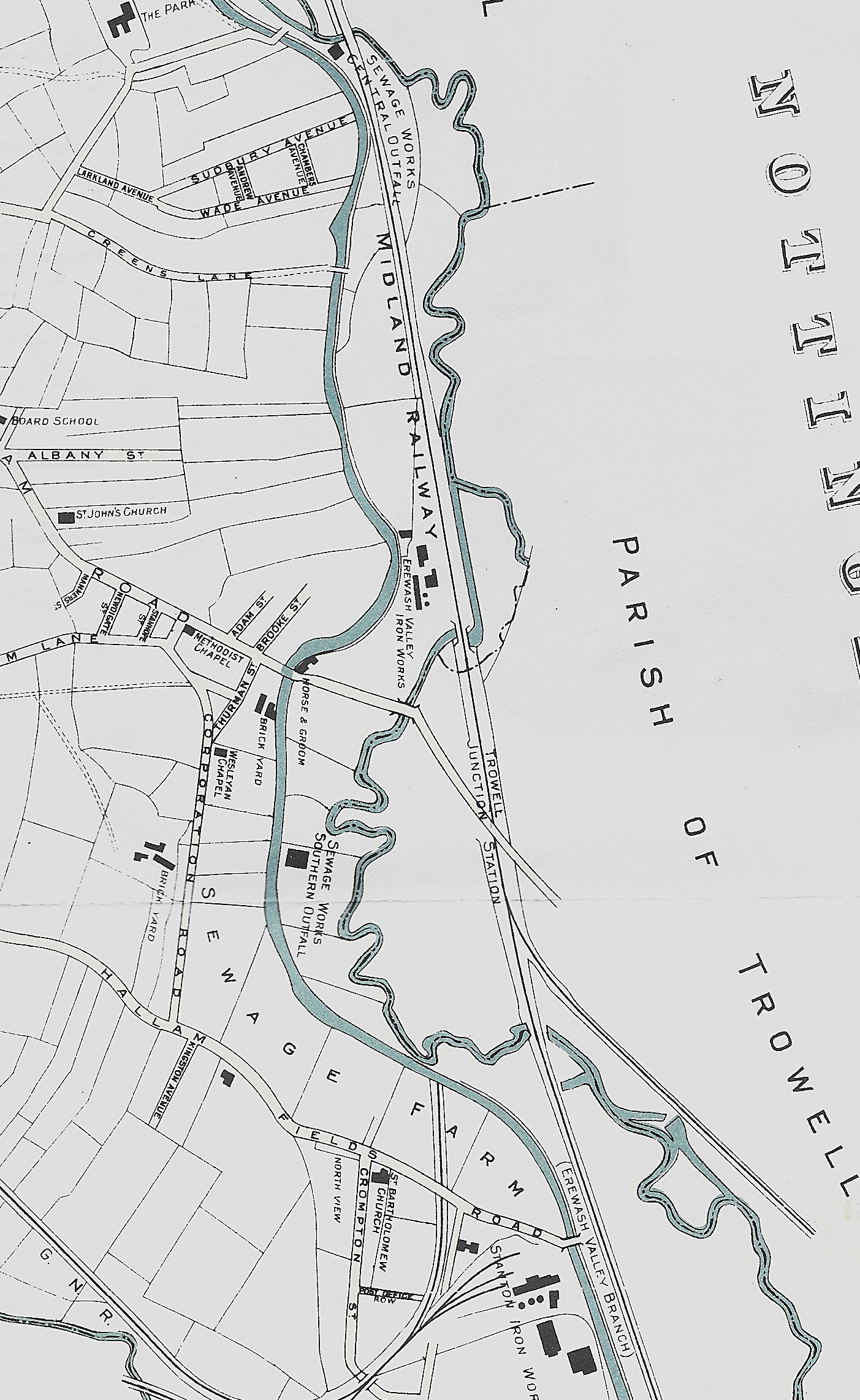

Location of the Sewerage works and sewage farm from a map of 1886 (revised in 1898) from Trueman and Marston

Another of these ‘catch pits’ near the Midland Town Station was visited, after which the party drove to Hallam Fields to inspect the farm. Some distance from the farm proper is the ‘screen chamber’ through which the total volume of sewage can be directed on to any part of the farm, or into the Erewash, if necessary.

Close by is a ‘sludge pit’ intended to clear the tank of sludge. From here, up to the farm, trenches have been cut in the fields along which the sewage could flow, and Mr. Blundell said that the holder of this land could see that the sewage did not run on to any one spot for too great a length of time, or it would kill the vegetation. The sewage must be kept moving, or it would do more harm than good.

Prceeding to the farm proper the party were met by Mr. Crompton, J.P, and by Mr. Hopkin, representing the Stanton Iron works Co., the owners of most of the property in the locality, and who endeavoured some time ago, but in vain, to dissuade the Board from carrying out the scheme, on the ground that it would prove a nuisance to the locality. The various parts of the farm were now inspected, and the sewage was turned out on one of the prepared filtration beds for the first time by Mr. W. Wade. (Like breaking a bottle over the bow of a ship about to be launched ?)

The work is considered to have been carried out in a most satisfactory manner by Mr. Cunliffe, and it was hoped that the scheme would answer the expectations of the Board, and set at rest the long vexed question as to the disposal of the Ilkeston sewage. …. The total length of sewage from Botany Bay to the farm is between three and four miles. (Leigh Chronicle and Weekly District Advertiser April 25th, 1884)

Benjamin’s faith in contractor William Cunliffe’s work wasn’t entirely well placed. By the time William submitted his final bill, in August 1884, the total cost amounted to £4958 8s 1d with a disputed sum still outstanding, owed to William. However the Board decided to hold back this final payment until all the defects which Benjamin had identified had been had been corrected … a decision which was soon reversed !! And by May 1885 the Local Board had the approval of the Local Government Board request for a loan of £4000 to finance the sewage works.

Further investment and improvements in the 1890s

Foul and and disease-ridden hovels still existed in some parts of Ilkeston. New sewerage facilities didn’t make them suddenly and magically disappear. This article from the Ilkeston Advertiser (July 1883) exemplifies the problem.

“Death from English cholera at Ilkeston –the sanitary condition of the town.

Considerable anxiety was occasioned in Ilkeston on Sunday morning (July 1883) when it became known that a child named Bostock, aged about four years, had died at 8.20 a.m., in Pimlico-place, from English cholera.

It appears that the child, who belongs to the ordinary working class, was taken suddenly ill on Friday. It became by rapid degrees very much worse, soon after it was first seized with illness, and suffered from vomiting, purging, cramp, and convulsions.

Dr. Wood was sent for, and upon attending the child, was satisfied that it was afflicted with English cholera. He applied all the remedies within his power, but in spite of the most skilful and careful medical attention the child died. Very soon after death the body turned completely black.

It may be explained that Pimlico-place, where the child lived, although occupying one of the most elevated positions of the town, and within a stone’s throw of the Town Hall, the headquarters of the Local Sanitary Authority, is one of the most foul spots in the place. It appears that in addition to a general state of very bad sanitary arrangements the neighbourhood of the house where the disease in question was contracted and the child died is rendered additionally obnoxious and unhealthy by people keeping pigs. Refuse, it is stated, has been allowed to accumulate until it forms a large heap, and the liquor runs down the small yard immediately facing the door of the house where this fatal case of disease has occurred. The deceased was playing about this spot during Friday before it was taken ill.

Recently the dreadfully obnoxious exhalations of sewer-gas from the gratings in the Market-place, at the corner of the thoroughfare known as Pimlico, and in Bath-street have formed a fruitful topic of comment, and some letters have been addressed to the local newspapers on the subject, but at present there is no change.

The smells continue, and it is stated that there is some cause to fear, although precautions have been taken to prevent any further result from the deplorable case that has already occurred, that unless some decided steps are taken by the proper authorities to speedily prevent the constant uprising of the noxious gas that is now daily encountered in the town, something more alarming than a solitary death through bad sanitary arrangements will take place”.

Time for another public inquiry ??

In 1881 and 1885 the Local Board had borrowed a total of just over £15,000 to adopt and then improve an irrigation system of sewage disposal. By 1894, of that total debt, about £8500 remained unpaid, but the town now had a complete system of sewers and a new sewage farm at Hallam Fields.

However in 1893 both the Erewash Canal Company and the County Council had complained that some of the town’s sewage had found its way into the canal and the river Erewash — and this had better stop or else !! The Canal Company had even gone so far as to impose a penal agreement upon the Borough Council which had to do something quickly or face a severe fine. The solution was to adopt the ‘Universal’ system of sewage purification, a solution not accepted by the Board Inspector, because the ‘Universal’ system was not recognised as safe. In July the Board Inspector conducting the Inquiry didn’t like the Council’s scheme; there wasn’t sufficient land set aside to pass the effluent over before it was pumped into the River Erewash. The Council therefore agreed to modify its scheme and then come back to the Local Government Board for (another go at) approval …. and come back it did !!!

By June 1894 the Town Council had applied to the Local Government Board for permission to borrow £7500 to finance a new sewage scheme, which of course necessitated a visit from a Board Inspector — in this case, Major-General Henry Darley Crozier. The loan would pay for additional sewers and disposal works. However the loan amount was soon increased by £500 to £8000 when the Council decided it needed to buy two new gas engines to pump up sewage sludge, thereby replacing manual labour.

On January 8th, 1895, before a different inspector, another inquiry was held at which the Town Council presented a slightly modified scheme to the one put forward in July of the previous year. The ‘expensive magnetic carbine filters‘ were abandoned but the ‘precipitating tanks‘ were retained, and much more land in several areas was set aside for dealing with the effluent from those tanks. A decision was expected shortly !!

The Sewage Works at Hallam Fields in 1913

———————————————————————————————

And now let’s rejoin Adeline as she takes us on, to meet the Sudburys