Past the row of three shops but below Jack Lee’s yard and up some steps were the old Smedley’s Alms Houses.

In a letter to the Pioneer in 1917 an Old Resident described this area.

The gable end of the six one-storied almshouses faced Bath Street, standing about three or four yards back, with a tree between the houses and the street boundary wall. In this end was a stone reading “These six houses were built in the year of our Lord 1744 by the pious benefaction of Richard Smedley, of Risley, in the County of Derby, and endowed by him with Five Pounds a year to each house, for ye maintenance of six poor people”.

They were sometimes referred to as ‘Bead Houses’. (Definition: “A dwelling for poor religious people, located near the church in which the founder was interred, and for whose soul the beadsmen or beadswomen were required to pray”).

In January 1881 John Wombell, editor of the Ilkeston Pioneer, wrote to the Charity Commission:

“Permit me to suggest to you the desirability of instituting an Inquiry as to the distribution and management of the Ilkeston Charities”.

For several years there had been complaints about the management of these charities but John had been lately energised by the recent failure to distribute Gisborne’s flannel charity on St. Thomas’s Day – December 21st.

John hinted at the presence of other irregularities which a thorough investigation might reveal.

Thus in March 1881 a Government inquiry was held at Ilkeston’s Town Hall to establish what “endowed charities are subsisting in the parish of Ilkeston, and the several foundations, endowments, and objects of such charities respectively, and also their present circumstances, and whether any and what improvement may be made in the management or application thereof”.

Ten charities were subsequently identified, of which three were wholly or partially lost. They were usually money, property or land bequests made by individuals, and the interest and income from them were used to benefit local people in some form.

The ten charities were –

Flamstead’s – at one time there were cottages and land belonging to, or supposed to belong to, this charity, plus 10s per annum paid to the vicar and to be distributed by him. In his will, dated October 13th 1684 John Flamstead had left a copyhold field and at least one cottage, the monies from which were to be distributed amongst some poor widows of the parish, yearly for ever.

John Francis Nash Eyre, the Vicar of St. Mary’s Church in 1881, stated at the inquiry that he had never received any money and the houses, though still standing, were now believed to be privately owned. Thus the charity should be regarded as lost.

The Pioneer was scandalised. “This is an eminently lame and impotent conclusion”.

The newspaper considered that a little simple research could uncover the property belonging to the charity. It must be somewhere!! It could not have disappeared!!

In 1889, while alterations were being made to the Parish Church, two tombstones were found under the chancel floor.

On one was the inscription “Here lyeth the body of John Flamsteed of Little Hallam, gentleman, who dyed December ye 15th, 1745, aged 72”.

It was reported that the grandfather of this John Flamstead was the uncle of the Astronomer Royal of that name, while his father, also a John Flamstead, in his will dated 1684, was the one who set up this charity.

(The second tombstone was of “Templer Flamsteed, son of John and Ann Flamsteed, who was born October the 22nd, 1712, and departed this life April the 6, 1713”).

Thomas Hunt’s – in his will of March 19th 1683 he gave land – Tinker’s Croft — to Ilkeston, the rent from which was to be distributed amongst poor widows, yearly for ever, upon the feast day of St. Thomas. (Tinker’s Croft was just north of Pimlico)

On St. Thomas’s Day 1874 (December 21st), John Francis Nash Eyre, the recently-arrived Vicar of St. Mary’s Church, gave away the charity gifts to the poor widows and the deserving poor, a distribution costing £68. The Vicar had been determined that only ‘certain classes’ should be recipients. However on that bitterly cold day numerous applicants arrived who were clearly ‘unsiutable’, using repeated outbursts of foul language and ribald jokes. Having weeded them out, the Vicar and his Churchwardens then allocated 1s or 2s each to about 300 people, while 150 widows received 4s or 5s each.

In 1879 some of the land had been sold to the Gas Company and the proceeds invested in Government securities, the dividend from which was distributed on St. Thomas’s Day amongst the poor of all denominations. Nearly one acre of this charity’s land was unaccounted for.

It became known as St. Thomas’s Day Charity. On December 21st, 1885 it was distributed from the Town Hall by the Churchwardens when about 400 ‘indigent persons’ each received a small sum of money, totalling about £70.

William Gregg’s – in his will of August 5th 1690 he left £20 to purchase land to yield income such that 20s per year could be paid in perpetuity at Easter-eve to eight of the poorest people of Ilkeston. The land purchased was called Bull Balk Close, Carr Close and Court Close, all lying together off the east side of Awsworth Road, up to the Erewash Canal. (* see below)

The finances of this charity appeared in good health. However some income derived from the recent felling of several of the Charity’s trees and the sale of their timber appeared to have become mixed up with the Rev. Nash Eyre’s account and thus lost to the charity!!

Samuel Roe’s – in 1775 he willed £100, the interest from which was to be given to the poor, and a further £20, interest from which was to be paid to the minister of the Protestant Dissenting Chapel (the Unitarian Chapel in High Street).

According to custom the vicar and churchwardens of St. Mary’s had assumed control of the charity although they were not legally entitled to do so. William Shakspeare, minister of the Unitarian Chapel, had received one-sixth of the interest while the rest was doled to the poor.

In April 1898 the affairs of this charity were raised at a meeting of the Town Council.

Humphrey Courtman’s – he died in 1727 and left land in the Mill Field producing 7s per year for the use of poor widows and 15s per year for the purpose of teaching three poor children.

John Foljambe’s – in a will dated March 6th 1704 he left land and securities which would yield an income of 40s per annum for the benefit of 40 poor widows of Little Hallam and Ilkeston, and the rest and remainder to the poorest families of Ilkeston. Most of this was now lost.

John Day’s – in his will of July 14th 1749 he left money to be paid annually, 5s per year, to five poor widows of Ilkeston…. on St. John’s Day (June 24th). The present vicar said he had never seen any of this money which appeared to have now been lost.

Francis Gisborne’s – on December 6th 1817 he bequeathed money for an annual Christmas distribution of flannel and woollen cloth amongst the poor of 100 parishes in Derbyshire, Ilkeston being one of them.

In the town £5 10s went towards four yards of cloth for each man and two yards of flannel for each woman.

This was distributed by the vicar as directed.

When asked why he had not distributed the charity, as usual, at last Christmas time, the Rev. Nash Eyre said that he had not received the money from the trustees in sufficient time.

John Lowe’s – in March 1837 he left £100 to the minister of St. Mary’s, the interest from the bequest to be used for the benefit of the Church Sunday schools.

It was suggested — by the Rev. Nash Eyre, and for which there was little or no evidence — that the Rev. George Searl Ebsworth (vicar 1842-1863) had used the money to purchase fixtures for the vicarage and in lieu of which he paid £5 per annum for the benefit of the school. This practice had been continued by his successor James Horsburgh and by the present vicar.

However there was remaining confusion over what had happened to the money and over the present vicar’s description of events.

The Rev. Ebsworth vehemently denied that he had used to money to enhance the fixtures of the Vicarage and both he and the Rev. Horsburgh stated that the money had been deposited in a local bank where it had remained until it had been handed over to the Rev. Nash Eyre. Despite receipts to prove it, the latter could not remember receiving the money. Several witnesses at the inquiry – including John Wombell – pointed the finger of suspicion, clearly and unsubtly, at the present vicar such that he decided the simplest thing was for him to pay £100 and have done with it. (laughter in the hall). The Commissioner concurred.

Richard Smedley’s – in a deed of March 30th 1744 he left rent from land and property owned by him, part of which was to finance the building of the six Bath Street alms-houses to accommodate six deserving poor from several local parishes – Risley, Old Awsworth, Nuttall, Newthorpe, Dale and Ilkeston — with an annual allowance of £5 to each.

There was also £10 to pay for the education of 36 to 40 poor children in the Ilkeston parish, and money for a similar purpose in Heanor, Awsworth, Newthorpe, Bilborough and Strelley.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

When the Commissioner who was conducting the inquiry visited the alms-houses he thought that they were so dilapidated that the safest place for their inhabitants to be was outside the houses.

The premises were a disgrace to the town and should be pulled down immediately.

“The inmates hardly looked like human beings, and would be much better in the Union” (that is the Workhouse).

In 1881 there was one trustee of Smedley’s charity remaining, and he explained that several of the alms houses had been allowed to remain empty and untended so that money might accumulate for the purpose of repairs.

On the 1881 Census five of the six houses were occupied.

The one-storied houses stood on a site, about 1000 yards in length, of valuable building land, and it was suggested that perhaps they could be pulled down and rebuilt cheaper elsewhere. A shooting gallery had been established on part of the frontage and was encroaching onto the property of the trust.

The teaching of the poor children had not been carried out for many years and the bequest for that purpose had simply been paid into the funds of the National Schools in the parishes intended to be benefitted — this did not go down well with many Nonconformists in the area !!

At the end of the 1881 Inquiry a number of questions was raised by the Commissioner: ……………

Most of the charities were managed by the Vicar and churchwardens.

Were these people best placed to fulfil this function?

Perhaps the management should be vested in a group of permanent trustees, with the present managers as ex officio members?

Aside from the charity income used for educational purposes, should the rest of the money be given in doles and flannel?

Wasn’t this degrading and demeaning to the recipients?

Could better use be made of the charities?

In 1883 the Charity Commissioners introduced several changes to the government of Smedley’s bequest. Included in these was that the houses should now accommodate a maximum of three alms people who would each receive an increased stipend when funds allowed. When a vacancy occurred at the alms-houses the trustees were required to advertise for applicants.

The trustees also had the power to sell the present property and invest the amount realised.

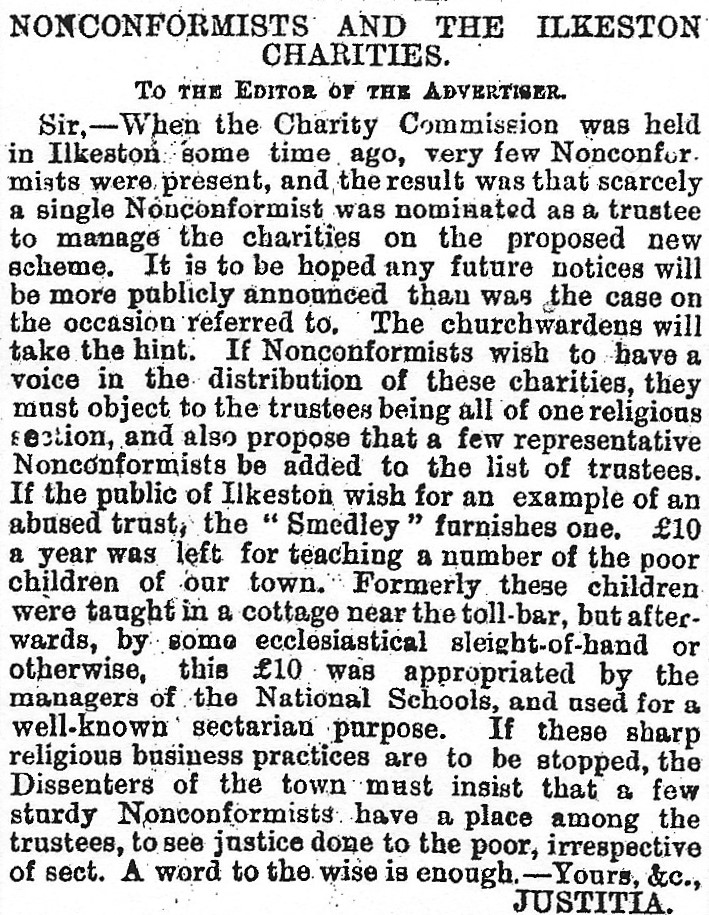

In September of 1883, following the inquiry by the Charity Commission, a letter-writer to the Advertiser raised the alarm for all Non-conformists in the town

After the work of the Charity Commission in 1883, an annual tea for the poor widows and aged poor of Ilkeston was provided at the Town Hall. On the second occasion the old people were “regaled with tobacco, &co., and a pleasant evening was passed with vocal and instrumental music”. Sufficient funds had been collected to later provide a tea for 400 poor children of the town also.

In December 1887 the Derby Daily Telegraph reported that the Charity Commissioners had just ordered the sale of building land, left to the poor of Ilkeston in the will of William Gregg (* above). It was in Park Road and was auctioned off by estate agent Edwin Sutton for £1320 to “Mr. Derbyshire of Nottingham”. This doesn’t quite fit in with the description of land (above) … was it a subsequent addition to the Charity’s holding of land but now sold off ?

Post script: In December 1932 the Pioneer noted that £104 was accruing annually from the sale of the almshouses and this sum was distributed by local dignitaries on the committee administering the charity to 400 recipients in the Town Hall.

“An interesting relic of the old Almshouses is the tablet in the Parish Church, which was removed when the almshouses were demolished”.

The alms houses were demolished in 1892.

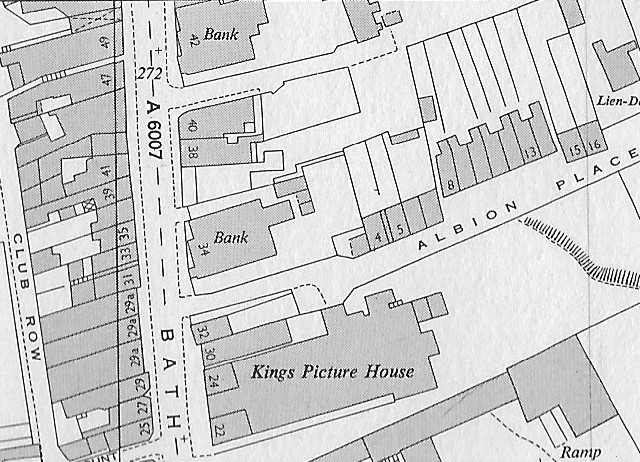

A branch of Crompton and Evans’ Union Bank then built on the site.

The Ilkeston Advertiser (1893) noted that “the new bank of Messrs. Crompton and Evans is rising into visible shape in Bath-street, and promises, when completed, to be one of the handsomest buildings in the town”. It opened for business in May 1894.

This joint stock banking company had been formed in June 1877 with the amalgamation of Messrs. Crompton, Newton & Co. of Derby and Chesterfield, and Messrs. W. and S. Evans & Co. of Derby.

On the right is the building in the 1970s (from the Jim Beardsley collection)

We have recently walked past two banks in this part of Bath Street … Samuel Smith & Co (at number 42) and Crompton & Evans, Union Bank Ltd. (on this page, at number 34). The latter later became the Westminster Bank and its careful demolition began in 1984

Here is a map (1959) to show their locations in a more modern setting. (Sadly the edge of the map cut off a bit !!)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Occupants of the Alms Houses.

Adeline recalls a few …. “Mrs. Widdowson, or ‘Weeping Mary’ as she was familiarly called, (a nurse) lived in one (of the alms houses);

a tall old lady – I forget her name – lived in another. To eke out her tiny income, she made small custards which she sold in the Market Place on Saturday nights. Her little stall was next to Charles Chadwick’s, the greengrocer. Her custards were much appreciated, and she usually disposed of her stock early in the evening.”

Mary Widdowson appears on the 1871 census, with her husband, at No 6 Alms Houses.

I believe that she was born Mary Ann Roome in Derby about 1812 and married widower and framework knitter William Widdowson in December 1839.

William died in June 1873 and in February of the following year Mary married Humphrey Rigley, coal carter of Nottingham Road. This was his third marriage but it was not to last long — Humphrey died in July 1875.

Mystery alert!! What happened to Mary?

Sheddie Kyme recalls two ‘Market’ dames, residents of the old Alms Houses, who made a display of confectionery, and when in season, stewed pears was a speciality of theirs at the Saturday markets.

“They would sit at the stall with their elbows in their knees, gazing into a coke fire, like witches into a cauldron”.

It seems that local shopkeepers would also supplement their trade with a stall at the Market. Bath Street tradesmen Charles Chadwick the greengrocer, Wilkinsons the pork butchers, James Henshaw, selling fish and rabbits, and South Street pork butcher Thomas Ball were all such tradesmen.

“Also living there was a blind man called Blind Billy.”

‘Blind Billy’ was William Smith, living with his wife Mary (nee Skeavington) in the house furthest from Bath Street.

The couple appear living at the Alms Houses on all censuses from 1841 to 1861.

Billy died at the Alms Houses of pneumonia on June 11th 1867, aged 64.

Thereafter Mary appears alone until 1881.She died there in September 1881, aged 73.

As an old resident recalled, the couple would sell ‘toffee, twist and drops’, and Billy would count out the sweets instead of weighing them. His best sale was in sticks, about six inches long, wrapped in paper and costing half a penny each.

“Many a time I have gone on Sundays to his house for a ‘penn’orth of ‘all sorts’ for Billy …was not averse to doing a trade on the Sabbath day. Hour after hour he has stood against the wall at the Bath-street end of the Alms-houses, listening to the footsteps of those who passed by, many of whom had a cheering word for the poor old blind man’. (a 40 years’ resident. IP 1900)

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

And we have at last arrived at Jack Lee’s Yard.