We leave behind Butcher Twells’ shop and field , and walking only a few yards we meet yet another butcher. As Adeline points out “the shop next to Twells’ field was a butcher’s shop”. Just so that you might locate where we are, on a modern map, we stand at the north corner of Bath Street and Northgate Street.

In 1840, this butcher’s shop belonged to William Riley and was approximately opposite to the Poplar Inn.

Born in 1813 William was the son of Bath Street grocer and butcher Thomas Riley and Hannah (nee Walker) and had been apprenticed to butcher Thomas Critchley of Ilkeston before setting up his own trade.

On December 27, 1836 he married Maria Straw, eldest daughter of lacemaker Thomas and Eliza (nee Pares), one of the several Straw families then living in Boot Lane (later Stanton Road).

In the Nottingham Review (April 19th, 1844) Thomas was described as “a thorough-going Churchman and old English Tory” who had just been appointed Churchwarden. And writing in the Ilkeston Pioneer of 1892, the anonymous correspondent Bath Street described William as ‘a capital man of business, an admirable judge of beasts and excellent company, but somewhat unfortunate’. Perhaps ‘somewhat unfortunate’ was a reference to the fact that in 1861 William was declared bankrupt when, at his bankruptcy hearing, he was described as a careless book-keeper.

William’s financial problems perhaps could be traced back to 1840 when he took ownership of these premises in Bath Street. And here we thank Jim Beardsley and his illuminating collection of documents from which the following account is compiled. Jim has kindly let me examine them on an extended loan period. Of course, any errors in the account are as a result of my misinterpretation and no-one else.

——————————————————————————————————————–

The Thomas Critchley Estate: Part 1

Living in Bath Street, opposite the Poplar Inn, Thomas Critchley was a prominent and prosperous butcher who died on September 2nd, 1839. His wife Ann (nee Critchley) had died three years before, in March 1836, and the couple were childless. In his will Thomas left some land to his nephew Samuel Whitehead, while the rest of his estate was entrusted to his two executors, George Blake Norman, surgeon, and Thomas Riley, grocer of Bath Street and the butcher’s nephew by marriage. The pair were charged with selling off the rest of butcher Critchley’s property and distributing the income between several of his relatives in the Whitehead and Higgitt families.

The gravestone of Thomas and Mary, standing in St. Mary’s churchyard and overlooking the lower Market Place

Thus it was that, just over two weeks after Thomas’s death, the executors offered for sale, by auction, all of the late butcher’s furniture, brewing vessels, linen, various live animals, hay, a quantity of manure, some fruit and cheeses, a cart and some fencing. This was followed by a second sale, two months later and again by auction, of much of the butcher’s land estate, divided into four parts.

Part 1 was a messuage with outbuildings, together with a neighbouring orchard and croft, all close to Ilkeston Baths. (… and a pew with an excellent situation in Ilkeston Church was included !!). As we shall discover later, this property lay along the north side of what is now Northgate Street.

Part 2 of the estate was described as a piece of grassland, of three acres, adjoining the previous offering and called ‘The Slade’.

Part 3 was then another area of grassland, of two acres, adjoining The Slade and called ‘Whitehead Close‘.

And finally Part 4 was another piece of grassland, just over one acre in area and known as the ‘Near Cort Close’, described as well-situated for building purposes, close to the Baths and on an ‘occupation road‘.

1840 and William Riley moves in

I am unsure how successful this sale was, but it might be that at least part of the Critchley estate was purchased by a relative. This is because, eight months after the butcher’s death, in April 1840, the two will executors appeared at Ilkeston Manorial Court, which dealt with local contracts and land tenure, as well as settling disputes. At this court the pair effectively sold part of butcher Critchley’s ‘landed property‘ to butcher William Riley (the son of Thomas Riley and grandnephew of Ann Critchley) for £250. This property was a cottage, formerly a barn, together with its outbuildings, yard, gardens, etc. where William, his wife and son were currently living. (Part 1 above). Also sold to William was a piece of land in Top Slade, again currently used by the butcher. (Part 2 above)

To help finance the property purchase he had just made, William reappeared at the same Court and on the same day, with his wife Maria, to apply for a mortgage on the property. This was granted, the mortgagees being Mark Attenborough, innkeeper of the Sir John Warren, and his younger brother William Attenborough, a Toton farmer; the sum paid was £200. William Riley was granted the right to pay off the mortgage (with a stipulated rate of interest of course)

These details are all contained in two documents, both dated April 21st 1840. Also mentioned in the documents is a horse carriage way and footpath into and out of the Top Slade and which continued into two other closes, called Nether (Bottom) Slade and Whitehead Close. (These two areas were situated at the north end of what was later to be North Street, roughly where Carr Street was and the Tesco Supermarket is). This road/path seems to have approximately followed the later route of Chapel Street into North Street.

There is an added note on the second document indicating that the mortgage was paid off and “satisfaction duly entered on the Rolls”

1840-1855; William expands, and takes on more debt

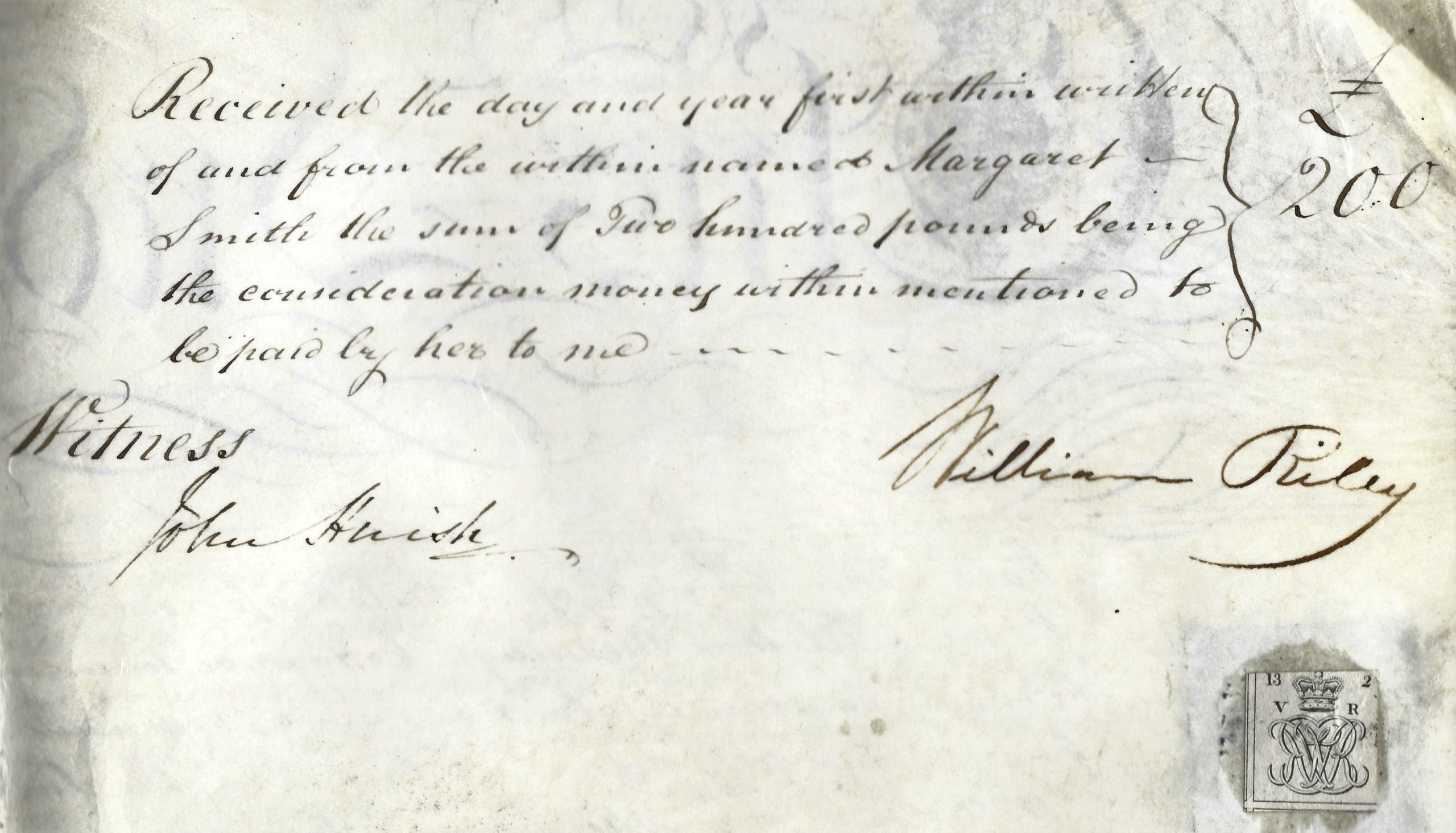

Within the next few years William Riley built a dwelling house and butcher’s shop, with outbuildings, on the yard of Thomas Critchley’s property which fronted Bath Street (Part 1 above). And in November 1843 he was back at the Manor Court where he borrowed £200 from Mrs. Margaret Smith of Bath, a widow, with William’s property as security. If he defaulted on the loan, then Margaret was granted the right of sale.

from the contract between William Riley and Margaret Smith, dated November 21st 1843.

And four months later, in a similar agreement, William and his wife Maria borrowed a further £400 from Margaret Smith, surrendering the Riley property to her as security until the money was repaid.

Margaret Smith died on January 30th 1850 and the executors of her will — Mark, John and Marcus Huish — agreed to the enfranchisement of Top Slade on October 28th 1853; thus it was converted from copyhold to freehold property. The loan of £400, earlier taken by William and his wife, was still outstanding, and the pair now borrowed a further £200 from the three executors. The security for the loan was the copyhold buildings occupied by William Riley plus the newly-enfranchised Top Slade.

In April 1854 and April 1855 two further loans of £50 each were made to William by the three executors, using the same copyhold and freehold property as security. On all these loans, interest had to be paid annually.

1860-1861 and William enfranchises, and takes on even more debt

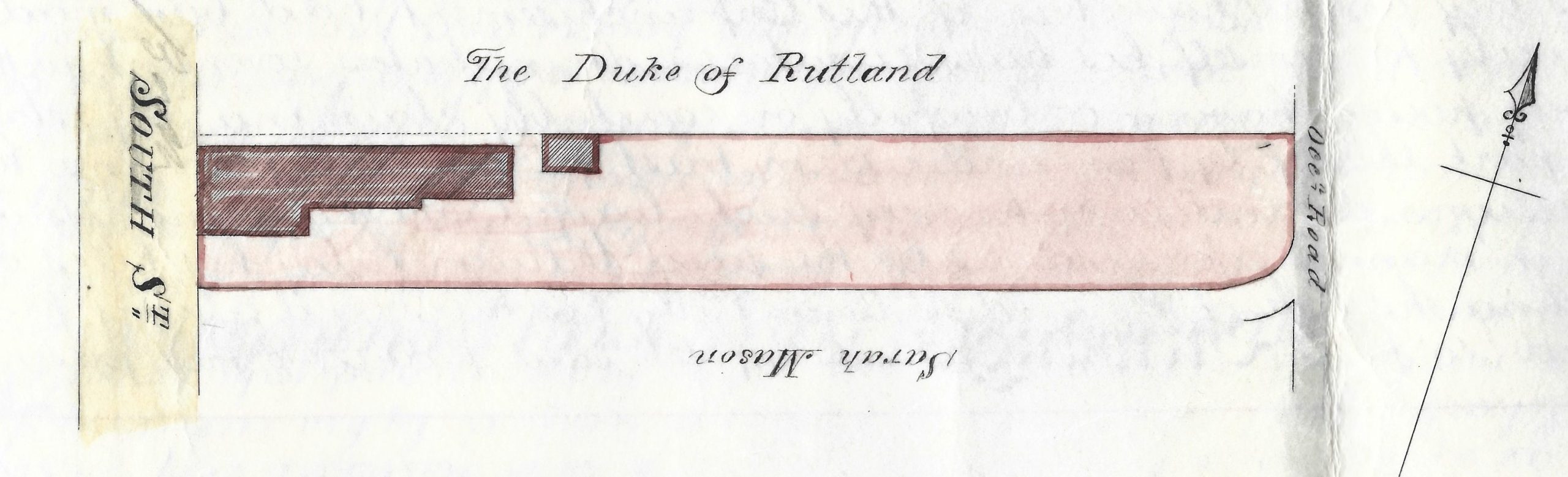

On March 8th 1860 William Riley paid a fee of £140 to Charles Cecil John the Duke of Rutland ‘and others‘ (namely Andrew Robert Drummond of Charing Cross, Frederic John Norman, Rector of Bottesford, and William Sloane Stanley of Paultons), and by so doing he enfranchised his property fronting onto Bath Street (see the sketch map below). This included the copyhold premises, formerly part of Thomas Critchley’s estate, and which William came to occupy in April 1840 — a cottage, outbuildings, yard, garden, etc — and also the dwelling house, butcher’s shop, and further outbuildings which William built on the original yard in the early 1840’s.

A sketch map showing the newly-enfranchised premises of butcher William Riley in 1860

I can only assume that the person who drew up this map was not familiar with Ilkeston; the street on the left was not South Street but Bath Street. William’s land is shaded and blocked. His southern neighbour was Sarah Mason (nee Lings), widow of Moses; she was to die in the following year. The lane between William and Sarah was later to be ‘North Gate’ or ‘Northgate Street’. And it would appear that Twells’ Field to the north, was still in the hands of the Duke of Rutland.

If you have been keeping count you will realise that at this time William Riley had accumulated a total debt of £700, owing to Messrs Huish, the interest on which he had paid regularly. Now, on April 2nd 1860, William paid off the principal of £700 to Messrs Huish, and just over three weeks later, he agreed a loan of £1411 15s 10d from Joseph Shaw, attorney and solicitor of Derby. In return William signed over the title deeds of his property as security. (This was the same Joseph Shaw, the High Bailiff of Derby, who in 1861 as we shall soon see, was implicated in financial impropriety — how are the mighty fallen !!?).

When the agreement between William Riley and Joseph Shaw was drawn up, on July 1st 1860, the sum borrowed by William had increased to £1600. Of this total, £400 belonged to John Adsetts, a land proprietor living in Duffield, Derbyshire; he lent the money to Joseph Shaw to help meet the full amount of the loan and so he too now had a claim on William Riley’s property. (John Adsetts will reappear later in the story !!)

In return for this loan William Riley thus mortgaged ….

…. the Top Slade,

…. the Public house occupied by John Trueman (later known as the Durham Ox — had William recently built or converted this ?)

….. seven houses recently built and adjoining the inn (in Belvoir Terrace/North Gate area), then occupied by his eldest son Charles William Riley, James Beardsley, William Bennett, Charles Stevens, Thomas Calladine, Charles Peters, and one other

… the original cottage with its yard, garden, outbuildings etc, acquired by William in April 1840

…. the dwelling house, butcher’s shop, outbuildings, yard etc. added by William in the early 1840’s

(It was noted that the latter two pieces of property had now been joined together to form one living area which William occupied)

…. all rights of way through and near these premises, together with any of outbuildings attached to them’

William agreed to repay the loan by January 1st 1861, and if it wasn’t paid by then, William would continue to pay the interest on the loaned amount or what was left owing. He also agreed that all the premises would be insured against fire, sufficient to cover the cost of the loan.

By January 1st 1861, William had not repaid the loan though he had paid the interest. Now he was asking Joseph Shaw for a further loan of £50 plus interest, a request which Joseph agreed to. He would now have possession of the Riley property until the total loan of £1650 was paid off. All other aspects of the previous agreement remained the same.

Not only had William Riley previously failed to repay the loan of £1600 to Joseph Shaw on time, but now he failed to repay the extra £50 loan at the stipulated date. His ‘careless book-keeping was showing‘ ?

1861; A financial maze

On February 15th 1861, Joseph Shaw himself was in need of a sizeable sum of money. Thus he asked William Riley to repay £900 of the loan he had made to the Ilkeston butcher; William was unable to repay. Joseph therefore applied for a loan from William Sampson, a prosperous farmer of Bent House in Church Broughton, Derbyshire. This was agreed and as a result, William Riley’s property mortgage and debt with Joseph Shaw, on July 1st 1860, was now fully transferred to William Sampson, as security for the loan of £900 to Joseph Shaw. As usual there was a proviso made that the lendee could repay the lender and thus absolve the debt; in this case however, the debt was not repaid on time.

(In March 1861 Joseph Shaw, then an attorney and solicitor practising at 36 Full Street, Derby, was appointed High Bailiff of Derby County Court)

Now John Tompson, a maltster from Erdington, Birmingham, was brought into the financial maze, He was owed several hundred pounds by Joseph Shaw who thus agreed, on July 13th 1861, to pass over his stake in the William Riley loan.

And at this point Herbert Wright, Birmingham attorney at law, entered the story. He was owed £790 by Joseph Shaw, and in a complicated arrangement, drawn up on September 20th 1861, he was included into the mortgage agreement of William Riley’s property. In future, if there was any default on loan repayments, then it was agreed that the property could be sold, and from the receipts, firstly the £900 would be repaid to William Sampson, then the money owed to Herbert Wright would be repaid, and finally any surplus would go to Joseph Shaw.

1861; William is bankrupt

But all this had caught up with the Ilkeston butcher. About March 18th 1861 William Riley was declared bankrupt but arguements over his property did not end. John Harris esquire of Nottingham was appointed the Official Assignee — it was therefore his job to distribute William’s assets to his creditors. Philip Potter, Ilkeston coal master, and Robert Harrison the younger, coal agent of Eastwood, were both appointed as Assignees for the Creditors, tasked with pleading the case of those owed money by William.

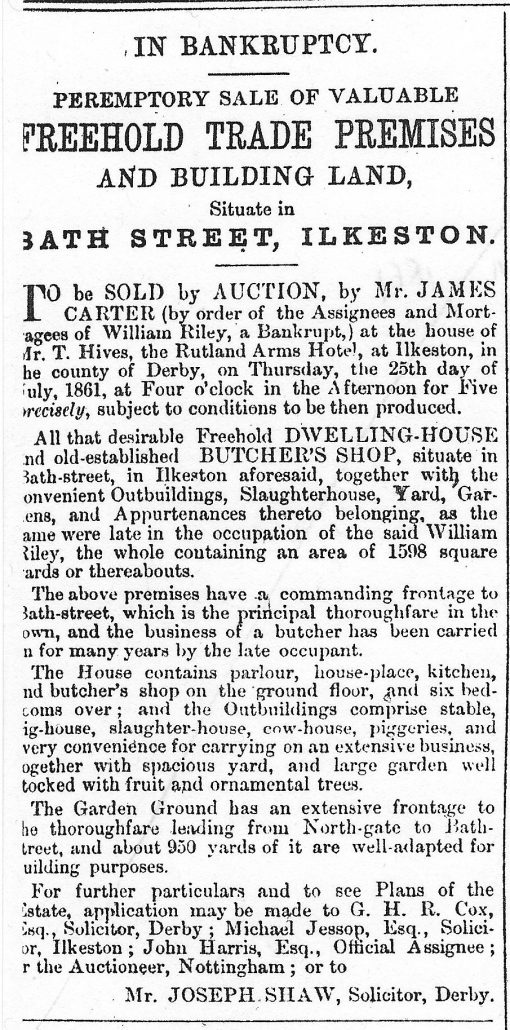

The butcher’s premises were subsequently sold at auction.

The description of them to prospective buyers listed a dwelling house with parlour, house-place, kitchen and an old-established butcher’s shop on the ground floor and six bedrooms above, with a commanding frontage to Bath Street.

Outbuildings included a stable, piggeries, slaughterhouse and cow-house, with a spacious yard and a large garden containing fruit and ornamental trees.

This garden ground had an extensive frontage to the thoroughfare leading from North-gate to Bath Street, with about 950 yards well suited for building on.

The whole property covered about 1598 square yards.

The accommodation needed to be extensive to provide accommodation for William, his wife and ten children.

Right is the Notice of bankruptcy in the Ilkeston Pioneer July 11th, 1861

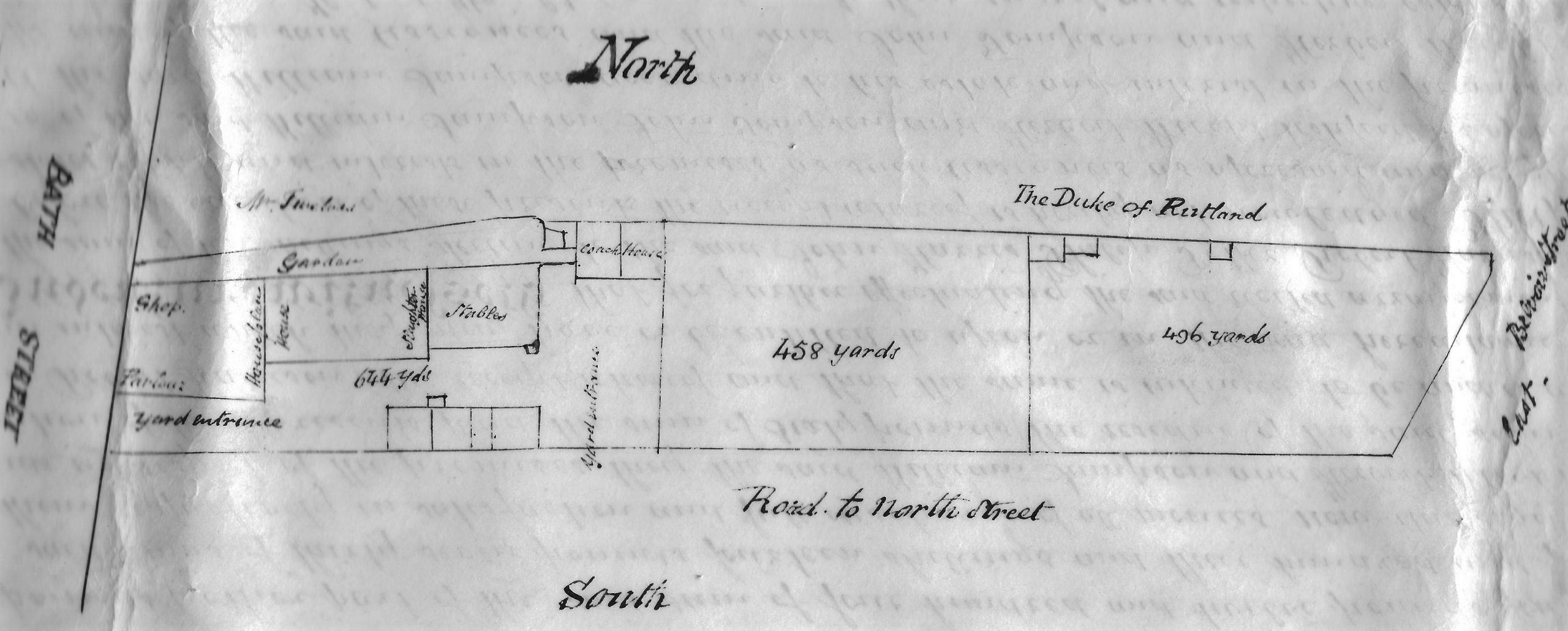

Although drawn a couple of years after the sale, the plan below gives an accurate view of what the Riley family were soon to leave behind.

Sketch of the Riley premises dated January 13th 1863

Reading from the left, which of course is West, you can see on the premises, a shop, parlour, yard entrance, houseplace, house, garden, slaughter house, stables, yard entrance, coach house.

The dimensions are clear, as are most of the features bounding the Riley premises, except, perhaps, Mr.Twelves in the North-west, and Belvoir Street in the East (This later became Wilton and Durham Streets).

————————————————————————————————————————————-

The Riley family leave Ilkeston … and England

Shortly after his bankruptcy William and many of his family left Ilkeston to settle in Berlin, Ontario, Canada and there “he spent his last days”.

His wife Maria died there, aged 50, in September 1867, “after a long and severe affliction”.

Daughter Hannah Walker Riley married potter Joseph Oliver Wade in November 1876 at St. Paul’s Church in London, Ontario.

‘Bath Street‘ again…. William “had a family of very intelligent children, Tom being, perhaps, the brightest. He told me a good story more than twenty years ago. When in Toronto he was fond of arguing on various topics, and could always hold his own. When asked where he was educated he said, “My father paid tuppence a week for me at a National School”. The work was done in the old school over the Butter Market, although it had no class-rooms, and the desks were ranged along one of the walls”. (see Education in Ilkeston).

—————————————————————————————————————————————-

This saga of Thomas Critchley’s Estate will be continued here.

————————————————————————————————————————————-

Looking out from Bath Street and across Twells’ Field we can locate John Trueman and the Durham Ox