My thanks to Katherine Ellis for providing such interesting detail on this Haslam family.

Walking from the old White House we come to the premises of George Haslam.

The Haslam family members

George Haslam was born in Mapperley on May 27th 1841, about four miles from Ilkeston, He appears on the 1841 census (June 6th) for Mapperley Village, aged one week old, living with his parents, coal miner John and Diana (nee Godber), and siblings Mary Ann and Eliza.

John and Diana had married at St. Mary’s Church, Ilkeston on December 24th 1833 — she was the eldest child of James and Ann (nee Lawrence), married on June 25th 1811 at St. Leodegarius Church, Basford.

Most of the Haslam family remained living at Mapperley while as a youth George was apprenticed to wheelwright Joseph Watson in Heanor. In 1864 he married Sarah Ellen Wright, the daughter of blacksmith Edward and Mary (nee Henstock), at the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in Ripley. They remained in Heanor, where their children Mary Hannah (1865), John (1866), Sarah Ellen (1868) and Elizabeth (1870) were born. There seems to have been a short-lived trip up to Bridlington where the family appear on the 1871 census and where son William Arthur (1872) was born.

Bertha (1873) was born in Heanor while the subsequent children were born in Ilkeston — Ann Eliza (1875), Florence Ethel (1877), George Edward (1879), James Godber (1880), Ada Gertrude (1882), twins Alice Wright Hilda and Martin Luther (1883), and Joseph Owen.

From the left, on the back row..

Ann Eliza (Nancy), remained a spinster and trained as a nurse at Bagthorthe Hospital in Nottingham.

Bertha married Harold Freer Sanders at the Bath Street Wesleyan Methodist Church in 1897. He was Professor of Theology at the Congregational Institute in Nottingham. She died in 1930. There was one son, Stephen (1898)

This could be John who was an architect’s assistant and became a partner with his father and brother William Arthur in 1892. However he died of typhoid fever at Euclid House on May 7th 1893, aged 26. (This could be William Arthur)

Mary Hannah (Polly), the eldest child, married James Thomas Stafford in 1895 at Ilkeston Independent Chapel. There was one son, John Thomas Wesley (1897)

Sarah Ellen (Nell) married William Manaton, a tailor and outfitter, at Bath Street Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in 1890. They then lived at Braunton near Barnstable. Their children were Fred Haslam (1891), George Aubrey (1892), Arthur John (1894), Doris (1896),

The next young man could be William Arthur, also an architect’s assistant and partner with his father and brother John, and who died in July 1894, aged 22, also of typhoid fever. He was shortly to be married. (This could be John)

On the end of the back row is Elizabeth (Lizzie) who married Edgar Thomas Slack, an ironmonger’s assistant, in 1897 at Bath Street Wesleyan Methodist Chapel. Their children were George Edgar (1899) and Doreen (1901).

Seated in the middle are George Haslam and Sarah Ellen (nee Wright). Between them could be son James Godber (1880) who died in 1903, aged 22.

Crouching on the front row are ..

Florence Ethel (Flo) who married joiner William James Fritchley in 1911 at Bath Street Wesleyan Methodist Chapel.

Joseph Owen (Joe) emigrated to Australia and can be found on the Electoral Register of Georgetown, Kennedy, Queensland as postmaster in 1934. He died on June 14th 1959 at Oaklands Park, Springbank, Adelaide, South Australia, aged 74.

George Edward (Ted) married Ellen Selina Webb in 1911 at St Mary’s Church in Ilkeston. Their three children were Helen Mary (1912), Dorothy (1914), and George Aubrey (1916).

Ada Gertrude (Gert) married schoolmaster William Henry Hollis in 1903 at Bath Street Wesleyan Methodist Chapel. Their children were Edna (1904), William Gordon (1906), Joan Elizabeth (1914), and Sheila Gertrude (1922)

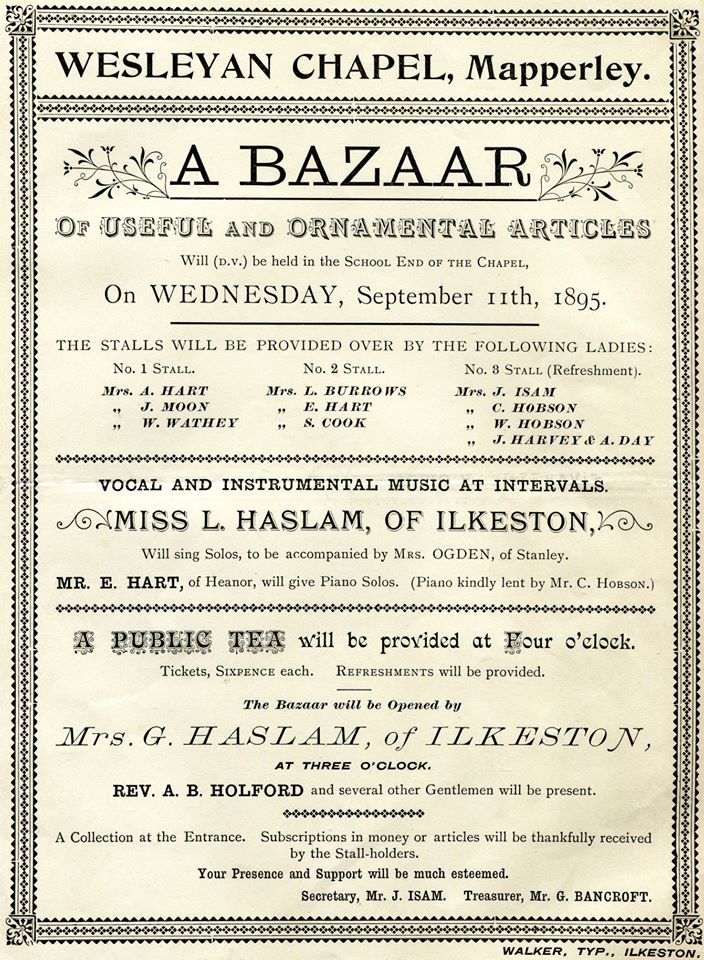

November 1893 : Success of an Ilkeston vocalist at a Nottingham Competition. At the first Midland Counties Solo and Choral Contest held under the auspices of the Nottingham Philharmonic Society, for contraltos and tenors, Lizzie Haslam secured the first prize, singing Joseph Leopold Röckel’s dramatic song, “Angus MacDonald”. Mr. Henry Miles, Mus. Bac., Oxen. F.C.O. was the adjudicator.

The Haslam family homes

When the famiy arrived in Ilkeston in the mid-1870s, the first residence was at No. 5 East Street, Ilkeston (below) ……

By the Spring of 1884 George was building a new house and shop in South Street and in June of that year his son, six-year old George Edward, was on the building site, walking on the scaffolding around the half-complete premises, when a plank lifted and sent him falling nearly 30 feet from the top of the building into the cellar. The lad fell on his head and injured his skull, such that it was feared ‘the worst consequences may ensue’.

They didn’t !

Their new South Street home was Euclid House — named after the Greek ‘Father of Geometry’ — at the southern corner of South Street and Queen Street. (photo below 2016 — note the symmetrical design).

On July 22nd 1884, George’s mother, Diana, died at Euclid House in South Street. She was aged 71. She was packing up her things, preparing to leave for a day or two, when she quite suddenly collapsed and died almost instantly.

George’s career

In November 1875 George was appointed Surveyor to Ilkeston’s Local Board, a post which he had relinquished by August 1881. This was not before George was awarded a ‘bonus’ of £150 in August 1880 for his plans and extra work in connection with the projected sewerage scheme for Ilkeston. Several Board members were not happy with this and as the town entered a more financially precarious period, George’s salary was reduced to £120 (June 1881). In 1884, when George had been succeeded by Charles William Hunt, the salary was confirmed at £120 p.a. although the Surveyor was relieved of the duty of collecting rates !!

In May 1881, at the first annual meeting of the Ilkeston Mechanics Institute, George was elected its Secretary.

In August of that year, as architect employed by the Local Board, he had drawn up plans for the extension of the town’s Gas Works, in Rutland Street, which had recently been purchased by the Board. They were subjected to extensive scrutiny by some of the more parsimonious members. For example Henry Clay questioned the need for glass in the roof of the coal-house and maintained that there would be sufficient light without it. George’s reply was that the men employed at the works had asked for some source of light — if no glass was provided then gas-light would have to be used — and this would mean extra expense of course ! The only alternative source of light was through the openings in the side of the coal-shed some seven feet high. When coal was stacked there, it might extend to that height and so cover thoses openings. And then came George’s plans to stain the woodwork of the shed — wasn’t this rather expensive and unnecessary ? George argued that it was just as cheap as painting it., but the retort came back — Why bother to do either ? And it was rather late in the day for all this discussion — and too late for any alterations. The plans had to be voted upon, which is what happened — the plans were passed, but George was not the most popular man with several members of the Board. “It’s sickening. I’d as soon go and get drunk”, murmured one.

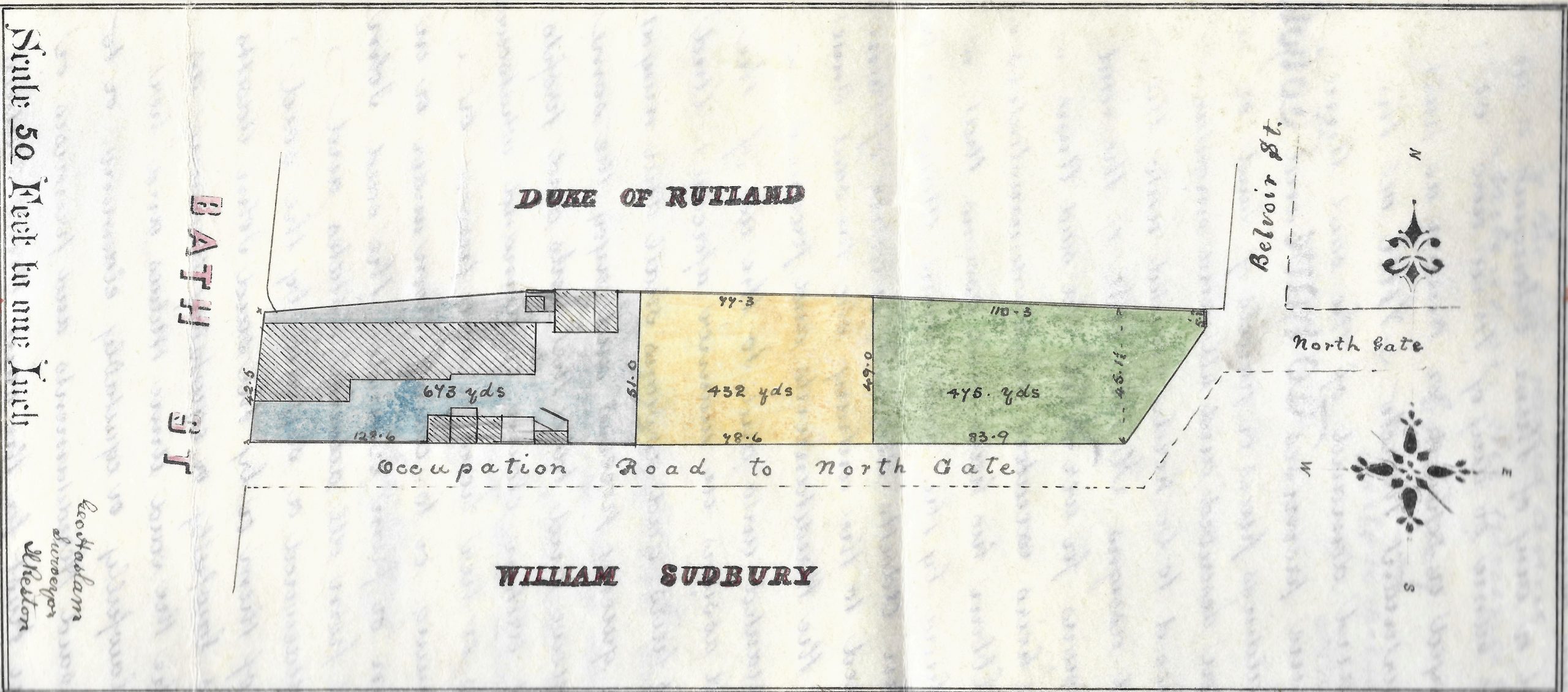

Below, on a Conveyance of Bath Street Property, dated November 2nd 1881, here is an example of George’s private work (from the personal collection of Jim Beardsley — many thanks !!)

And by May of 1882 George, ‘late surveyor to the Ilkeston Board’, had just worked on designing the plans for a new sewage scheme for the old Ilkeston Board, which had been adopted by that Board and sanctioned by the Local Government Board. However since that time, a new Local Board had been elected and this had repudiated George’s scheme. George was furious and was now demanding £50 as payment for the time and effort he had already expended or else he would pursue his case in court. There was ‘animated discussion‘ within the new Board and it was decided that George would be paid — but only after he had lodged all his drawings and tracings with the Board. The ‘Liberal-leaning’ Ilkeston Advertiser, opposed to the new Conservative-dominated Local Board, felt that George was being ‘ill-used’ in that his payment was being deliberately delayed, out of spite or jealousy of his success.

In November 1882 Herbert Tatham died and this left a vacancy on Ilkeston School Board. A special meeting of that board, chaired by Charles Woolliscroft, was convened at the end of November, to elect a new member to take Herbert’s place. The Rev. John Fleming of the Congregational Church and Stephen Keeling both supported the appointment of George, as did the Chairman who was his close friend. All, of course, were Non-Conformist in religion and Liberal in politics. Charles described George as “a very suitable man in every way, seeing that they were about to build another set of schools … he was to a great extent a self-educated man, and a man of great energy and business habits. It was a matter of necessity to have a man of business capabilities, and one punctual at his post…. they would have such a man in Mr. Haslam”. The ‘Liberal’ Ilkeston Advertiser also believed that George ‘will be an active, practical, and valuable member, and one in whose judgement and efficiency the ratepayers will feel perfect confidence’. George was elected unanimously.

There was a second place available on the Board, resulting from the resignation of Samuel Streets Potter (who was off to America) and at this same meeting, this place was filled by the Rev. John Francis Nash Eyre. This meant, by agreement, one place for each of the Liberal and Conservative candidates.

In April 1884 George was appointed onto the Ilkeston Local Board… at the ‘election’ only five candidates were nominated for six vacancies !!!

April 11th… On the Good Friday night of 1884, about one am., architect and surveyor George Haslam was sleeping lightly in his bedroom at No. 5 East Street when he was awakened by a noise. Looking out his window and seeing nothing amiss, he was reassured to return to bed and to his slumbers. Had he investigated further he would have discovered the broken pane in his shop window and the absence of several pairs of the family’s footwear.

On that same night, about an hour later, PC. Payne was patrolling his path down Bath Street when who should he meet but James Noon. Perhaps it was the lateness of the hour which aroused the policeman’s suspicions, or, more likely, the 15 pairs of boots and slippers he was carrying under his arm. Recognising James as a returned convict he took him into custody. And later, architect George was reunited with his missing property.

Thus his craving for other folk’s footwear led to another appearance at the Assizes for James where he pleaded guilty and was back ‘inside’ — now for five years penal servitude.

(At this trial an alias of ‘James Alexander’ was mentioned though its source is not clear to me).

In February, 1885, as Hon.Sec. of the Ilkeston Liberal Association, George wrote to Lord Hartington, Spencer Compton Cavendish, Secretary of State for War, asking his lordship if he would consider becoming the Liberal candidate for the newly-formed Ilkeston constituency. Lord Hartington had had several competing offers and so he refused George’s plea … Hartington eventually chose the Rossendale Division of Lancashire, and was elected as M.P. there in the December 1885 Election.

George then approached Thomas Watson, a businessman and J.P. in Rochdale, who accepted !! Thomas won the Ilkeston seat in the 1885 Election, retained it in the 1886 Election, but died the following year.

In September 1887 George was elected as a member of The Society of Architects at the Annual General Meeting.

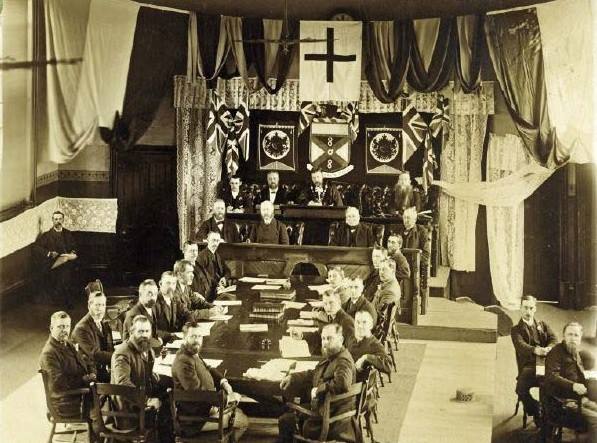

1887 saw the incorporation of Ilkeston, an event which meant the demise of the Local Board and the birth of the Town Council. But what did it mean for George ?? The answer can be found in the following two photos.

The last meeting of the Local Board in February 1887.

Seated are front row left to right: Charles Haslam, William Wade, William Sudbury, Francis Sudbury, William Tatham and Isaac Attenborough and unknown. Second row left to right: Walter Tatham, Charles Maltby, Frederick Beardsley, Samuel Richards, Samuel Robinson, George Haslam, unknown, Wright Lissett and unknown. Behind second row left to right: William Fletcher, Edmund Tatham, Joseph Shorthose, Edwin Trueman and three unknowns.

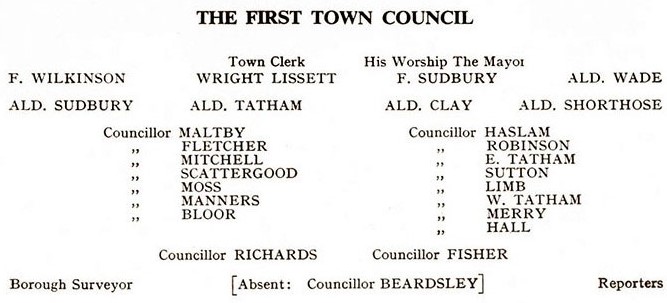

Ilkeston became a municipal borough on January 31st 1887 and this necessitated council elections to pick 18 members to sit on the new Town Council. Therafter the first Town Council met on May 9th of that year (photo above). If you follow the seating plan you should find George quite easily.

In the May poll to elect the councillors, George had gained the most votes. During the election campaign George had been aided by his wife Sarah Ellen and family who had all canvassed for him, and this had caused some rancour amongst other candidates. One of them — Richard Riley, an outspoken Radical and ‘Working man’s’ representative and, as it turned out, beaten candidate — later attacked George at a public meeting in the Town Hall, after the election. “Was it right to make it a matter for family prayer and supplication to be placed at the head of the poll ?” asked Richard. George was indignant. He was not ashamed of saying that he prayed for success in everything he undertook. As to his wife and family, all honour to them if they chose to go out and make him known to all his constituents. No reasonable argument could be brought against them for doing so.

In 1888 George was the Mayor’s auditor.

George had a tandem tricycle, worth £20, which was allegedly stolen in the summer of 1890.

It turned out that it hadn’t really been stolen but merely ‘borrowed‘ — by a young man named Arthur Middleton of Hallam Fields who was variously described as ‘a lunatic‘, ‘not fully responsible for his actions‘, ‘very peculiar‘, and ‘of weak intellect and deficient memory’ — take your pick !!

When Arthur appeared at the Summer Assizes in Derby, the magistrate asked him what his defence was, and Arthur replied “I would like to get off, sir”

And get off he did … not having intended to steal the vehicle.

As a post-script …. Arthur was a few days later apprehended at Chesterfield because of ‘his strange behaviour‘ and taken to the Workhouse, where he was assessed as a suitable candidate for Mickleover hospital. However before he could be conveyed there, he managed to escape from the Workhouse by squeezing between iron bars only nine inches apart.

Arthur did reappear, living in a hut on No-man’s Lane, Dale Abbey, and found himself once more in court — on June 6th 1895 — now being described as a ‘kleptomaniac’ but still of ‘weak intellect’. He had stolen a wheelbarrow from Councillor Charles Mitchell at Hallam Fields, a grafting tool from Stanton Ironworks, and a spade from Luke Marshall at Stanton by Dale. “I will try and do better in the future if the magistrates will let me off with a fine” promised Arthur on his arrest. He was committed for trial at the upcoming Assizes, and there he was sentenced to serve three months in jail for each of the three offences, the sentences to run concurrently.

And poor Arthur !! He really couldn’t keep out of trouble ! In January 1898 he was discovered “wandering abroad” on the Uttoxeter New Road at Derby in the early hours of the morning. He was taken to the nearby lock-up where it was discovered that he was wanted for stealing tools belonging to the Stanton Ironworks Company at Ilkeston. He was remanded in custody, escorted back to Ilkeston, and was later remanded to appear at Derby Assizes; there he pleaded guilty and his sentence was deferred until the next day.

And by the next day the judge had had chance to review Arthur’s previous testimony. The lad had claimed that his wife was in a serious condition and that his father had just died and was about to be buried. He had produced a letter, written in his own hand but supposedly copied from one written by “the Rev. W. Evans, Vicar of Ilkeston” (though the Vicar was ‘E.M. Evans’) which pleaded that Arthur be allowed to attend his father’s funeral. The judge believed none of Arthur’s assertions, though he knew that Arthur had been twice an inmate at Mickleover Asylum, in 1891 and 1893, but this didn’t stop him from assessing that the accused was “an artful, cunning person“, perhaps of weak intellect, aided by excessive drinking. He had no pity on Arthur who was sentenced to six months with hard labour.

And by the end of that same year Arthur had acquired an alias — Arthur Branston — and was appearing at Loughborough Petty Sessions, charged with stealing a pair of gloves, a collar and a necktie at Shepshed.

Courtesy of the Malcolm Burrows Collection held by the Ilkeston and District Local History Society

In November 1893 a bye-election was fought in the South Ward of the Town Council, necessitated by the retirement of Walter Tatham. George had been temporarily absent from the Council but now decided to try to join it once more, and so he put himself up for election. Standing against him was one other candidate, an official Liberal, John Hancock, hosiery manager of Holmdale in Station Road; he had been nominated by the South Ward Liberal Association, which meant that George, also a Liberal, had to stand as an ‘Independent’. John had the support of Benjamin Gregory, the local miners’ leader and Town Councillor, while George had a good many Church folk and Conservatives backing him. On election day (November 28th) polling stations were set up at the Market Hall in the Market Place, at Gallows Inn and at Hallam Fields. The local press reported on ‘little public interest‘, so not a lot of votes to count ?! Only 495 took time to vote, out of a total electorate of 1196 — 41%, not bad by modern standards ?? In the event, George came out victor, with 332 votes to John’s total of 159.

And in January 1897, George was advertising his talents in the Ilkeston Circuit Wesleyan Methodist Church Record

September 17th 1896 … and still a keen cyclist, George was on business in Leicestershire, cycling to work when he was discovered unconscious by the roadside near Castle Donington. As he was approaching the Station Hotel the front wheel of his cycle gave way and George fell heavily, fracturing his lower jaw. He was taken to a nearby residence while his family in Ilkeston were informed by telegram. His wife and a daughter drove over to find George in “a precarious condition”.

In May 1898 George chaired a meeting of the Committee promoting better accommodation for the south end of the town at the South Street Schoolrooms. George had recently been to London and had met with the general sub-manager of the Great Northen Railway Company but had been somewhat disappointed in the plans of the company with respect to the town.

In 1902 the Town Council had plans to build a Library for the town, with a market area adjoining … but it needed to borrow funds to do this. So, in February a Local Government inquiry was held in the Town Hall to explore this idea…. and George was present. There was plenty of available land as the houses bordering the south edge of the Martket Place, had long been taken down. Andrew Carnegie, the Scottish-American industrialist, had offered £7500 to finance the building of a free library, on condition that the town provided a site for it. George was a member of the Library Committee and he strongly supported purchasing the site in the Market Place area.

On July 17th 1903 the foundation stone of the library was laid by Walter Foster M.P. for Ilkeston.

The Library was built and opened on August 24th 1904 by the Marquis of Granby

George’s legacy

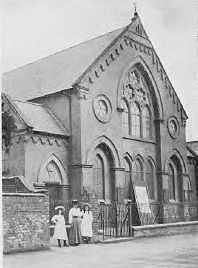

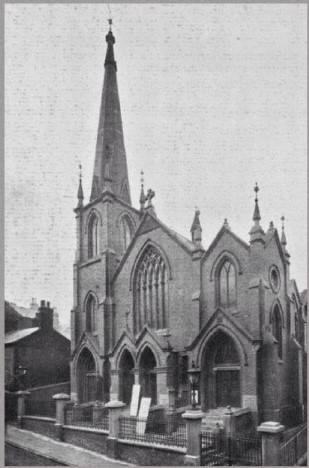

On March 11th 1886 the new Wesleyan Methodist Chapel at Stapleford, designed by George and seating up to 450, was officially opened. It was in ‘the Gothic style of architecture‘ with two main entrances, one to each side, and a large six-light window in the fascade. The schoolroom was at the rear, with the floor of the school level with the gallery floor. Internal fittings were of varnished pitch-pine and deal.

Stapleford Wesleyan Methodist Church

http://staplefordlocalhistory.org.uk/stapleford/religious/methodist.html

The Chapel was built by the Harper Brothers of Ilkeston and the woodwork was by William Richards also of Ilkeston.

*** My thanks to Alison Reid whose comments revealed that I had originally included a photo of Sandiacre United Reform Methodist Chapel, dating from 1866 (on Station Road by the Erewash Canal) and not Stapleford Wesleyan Methodist Chapel on Church Street in Stapleford. I have corrected this mistake (April 2022). Today, Alison and her family operate a business from these Sandiacre premises.(Colin Reid Bespoke Furniture Ltd.)

The Chaucer Street Board Schools

Towards the end of Summer 1887 the Town Council approved the site which had been purchased by Ilkeston School Board for a new school in Chaucer Street. George had by then prepared plans for the building.

The site for the new school, in Chapel Street East (ie Lower Chapel Street), was officially signed off by the Town Council in September 1887. It was agreed that it would accommodate 300 boys, 250 girls, and 300 infants. By October 1887 George was the only architect to have provided plans for a new schools and so they was chosen almost by ‘default’.

In May 1888 slightly amended plans were laid before the School Board — now the proposed Chaucer schools were to house 900 infants. The plans were passed unanimously and sent off to the Education Department where they were judged to be “convenient in almost all features”.

Tenders were now sought and, with a bid of £4032, William Small was initially chosen. However he couldn’t supply the necessary bond and the alternative tender of Samuel Shaw was therefore chosen, just over £200 more expensive. Shortly after this the School Board agreed that a loan of just over £5000 would be taken out to meet the cost of building the new schools.

In August 1889, William Edward Barton of King Street was appointed as the caretaker for the new schools, at a wage of 13s per week. And in December, Arthur William Higgett of Brixton was appointed Master of the new school

taken from the junction of Lower Chapel Street (left) and Cranmer Street (right)

a view of the school, the photographer standing in Byron Street. (Jim Beardsley‘s collection)

the school as we walk down Chaucer Street (Jim Beardley‘s collection)

The ‘new’ school was opened in September 1889 with Arthur W Higgitt as Head, and 4 assistants. A girls’ school extension was agreed and signed off in January 1892, and in November 1892 the tender to build the new extension submitted by Benjamin Keeling, master builder of Radford, Nottingham, was accepted. The new building was opened in 1894.

All the schools were demolished around 1980, and the site subsequently used for housing. A new Chaucer School was built nearby.

Kathleen Trueman has written (1988) an excellent account of the history of Chaucer School — “From Slate to Software, (another Chaucer Tale)” — original price of £2.50.

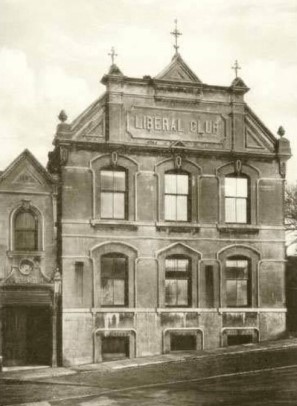

The Liberal Club designed by George Haslam

The original idea for a Liberal Club in Ilkeston came from William Tatham, lace and needle manufacturer of Stanley House, in 1886. A limited liability company was then formed, to raise finance for the scheme, and George was appointed as architect, his brief being to draw up plans for the alteration of a tumble-down property on the site to the requirement of the Liberal Club.

Many years before, the Anchor Inn had stood on this site, but this was followed by a shop and several dwelling houses belonging to Matthew Hobson and then to Paul Hodgkinson. These premises were purchased from the latter in 1886 for £2200 and it was these premise that were the basis for the new design, “which will show a handsome frontage to the Market Place”.

Built in 1887-8 by George Good, it was designed to accommodate all the Ilkeston party members … 300 in total. “The exterior of the club is of a neat and imposing character, and it is quite an ornament to the Market-place.The interior consists of entrance-hall, two spacious billiard-rooms, reading-room, committee-room, lavatory, and every other reasonable convenience.” (Leeds Mercury)

The building was officially opened on 31 May 1888 by the Marquis of Ripon and Walter Foster, M.P. for Ilkeston.

It was closed as a Liberal Club in December 1955. The building was demolished in the winter of 1960-1.

Adapted from the ‘Views of Ilkeston’ Series.

The basement was devoted to cellarage. On the first floor, a refreshment room and bar (19ft x 13ft 6in), a committee room (13ft x 12 ft), a billiard room with two tables (46ft x 18ft 6in). On the second floor, a reading room, a smoking room, another large billiard room.

The Long Eaton Advertiser (February 4th 1888) was generous in its praise of ‘the handsome and commodious club-house‘ … “the architect has worked a wondrous transformation with the materials at his disposal for what was a miserably forlorn building is now architecturally handsome and decoratively beautiful. …. there is no part of the club to which the honorary member is entitled to go, but the ordinary member has an equal right. The building is open to all members alike; the reading room will be prserved from the two practices to which some good souls object — drinking and smoking, but elsewhere the member will be at liberty to sip their beer, or indulge in the fragrant weed …”

The new Wesleyan Methodist Church in Bath Street … not the first one but the second one !!!

The 1870s were years of some turmoil within the Wesleyan Methodist Church following splits which had appeared among the members. And during this period there was some ‘interchange’ of chapel buildings

A (first) new Wesleyan Church in Bath Street was built, — on the site of the Fletcher factory. Initially a plot of land was purchased in Station Road but this was then thought to be no better a chapel site than their present Market Street home.

Subsequently, in the summer of 1872, the lace factory and land of the Fletcher family in Bath Street came onto the market and was purchased ‘by the Wesleyans of Mr. Richard Evans’ — for £495 — who enfranchised the property and conveyed it as freehold.

Soon thereafter the building of this new Wesleyan Chapel began, standing back from the main road to ensure quietness and privacy. This would be at the rear of the present Wilkinson store.

In 1875 further land was purchased, adjacent to and in front of the chapel where some old houses stood …. for £375.

And yet more land was similarly added in 1881. But it was to be 15 years later that the ambitions of the Wesleyans led to a second Bath Street Church being built — and its architect of this one was George Haslam.

The memorial stones for this new Church, built by John Henry Vickers and Son of Nottingham, were eventually laid in October 1896 and it was formally opened in March 1898.

Laying the foundation stone of the Wesleyan Methodist Church, October 14th 1896. (courtesy of Ilkeston Library)

We are looking towards Bath Street, at the premises of Leeds and Leicester Boot Co. (46 Bath St.) and at the Queen’s Head Inn, now much closer to the road (48 Bath St.) .

The new church of Gothic design, constructed of red bricks with terracotta and stone dressings at a cost of £5500, had a spire 120 feet above the street level and which caused some controversy at the time.

William Smith (1909) writes that “some of our friends were a little doubtful about the spire, but there was a purpose in it and it was meant to show all around what was going on”.

The same writer also records that many a traveller on the Erewash Valley line of the Midland Railway enquired what the spire was. One man, when asked was given the reply, “It‘s the new Wesleyan Chapel in Bath Street”.

“No, tisn’t”, said a boy correcting him, “it’s the Wesleyan Church in Bath Street”.

“Ilkeston was our climax, and we may fairly assume that for any time within vision so far as church building goes we have seen an ‘end of all perfection’, and no attempt will be made to rival or even come within ‘measurable distance’ of that noble building”.

There was seating for 940 adults and it was then the largest church building in Ilkeston. It was closed in 1968 and its demolition started in 1971.

The original chapel — the one built in 1872/73 — then became the Sunday School rooms for a new Central Methodist Church, built at the front of the same site.

————————————————————————————————————————————————

and on to the Nag’s Head in South Street.