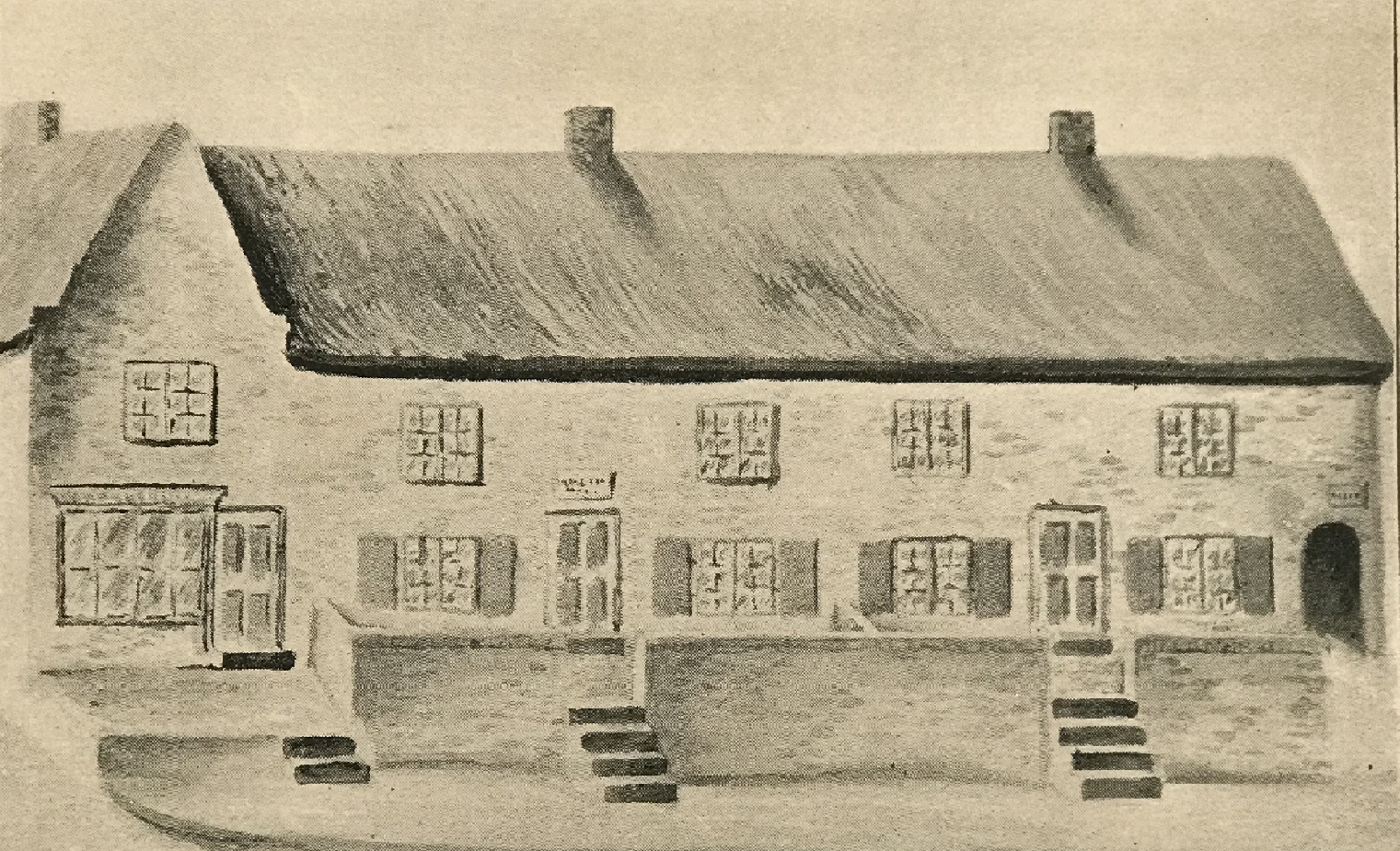

Before its building the site of the Town Hall was occupied by three or four old thatched and white-washed cottages belonging to farmer Mr. John Taylor of the Manor House, at the north of the town. The premises had been with his family since the time of his grandfather. John sold the land for £800.

Adeline recalls the buildings next to the Sir John Warren inn … “At the beginning of Pimlico, next to the Sir John Warren Inn, was a plain windowed shop, linked with three cottages built on the original bank. This was where the Town Hall now stands. These were separated by walls, and approached by steps.”

A sketch purporting to show the town hall cottages

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Fred Mitchell, shoemaker

“The first, for some time, was occupied by Fred Mitchell and his family. Fred was a shoemaker.”

Born in 1832, Fred Mitchell was the elder son of Abraham and Ann (nee Campbell), South Street shoe makers, menders and vendors, and the nephew of Alice Mitchell who had married Mark Attenborough, next door.

In 1852 Fred married a West Hallam-born girl, Cassandra Lee, daughter of framework knitter George and Judith (nee Wheatley).

After the death of his widowed mother in 1871, Fred and family went to live in the family home in South Street.

“He had four children”.

Ike, the eldest, who was rather slow.

Their first-born, Isaac (Ike), died as a young man, aged 22, in January 1876.

Emma, who married a Mr. Clark,

Only daughter Emma married Leicester-born clerk George Samuel Clarke in November 1873 and for a time the couple continued to live with father Fred, providing him with grandchildren, George Augustus, Agnes Gertrude, Frederick William and John Edward, before Fred died in August 1884 in Gladstone Street, aged 52 and five years after his wife Cassandra.

Harry and Aby or Abie

Two other sons were Henry (Harry) and Abraham (Aby or Abie) Campbell, the latter being given the surname of his paternal grandmother.

Harry worked as a shoemaker/boot repairer in Ilkeston and married Frances Louisa Bourne in 1884.

Abraham Campbell married Mary Cockayne, daughter of glove hand William and Mary (nee Henshaw) in February 1882, whilst working as a lace hand at Long Eaton — where the family remained for a few years before moving back to Ilkeston in the mid-1880s.

— Fred and Cassandra had two other sons …..William Campbell and Thomas Campbell … but both died in infancy as did daughter Sarah Ann.

Also living in Pimlico and trading as a shoemaker was Frederick’s uncle William.

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Thomas Mather, tailor

“The next tenant was Mr. Mather, tailor.”

Pigot’s Directory of 1835 lists Thomas Mather, tailor, living in Ilkeston, while the 1841 and 1851 censuses show him in Bath Street, residing with Mary Gregory (nee Skevington), widow of Isaac and daughter of Robert and Elizabeth (nee Garton).

In December 1851 Thomas married Elizabeth Straw, daughter of miner Joseph and Hannah (nee Shaw) of Club Row.

Elizabeth brought to the marriage her two illegitimate sons — John (born in 1847) and Thomas junior (born in 1849) — both of whom continued to live with their mother and adopted the Mather family name.

In September 1855 Thomas junior was riding a donkey near to the gas-works when he fell off and broke his arm.

In employment John was also a tailor while Thomas junior was a miner.

Subsequently the family grew and moved into Albion Place, thence into the Market Place while the 1861 census shows them in South Street, at the location suggested by Adeline. The family remained in this area for many years but moved into Burr Lane in the early 1880’s.

Whilst trading in South Street, Thomas senior and Elizabeth seem to have supplemented the family income by selling groceries.

One Saturday morning in 1872 Elizabeth was in a back room folding clothes when she heard someone at the shop-door. She looked through into the shop and saw a stranger lean over the counter, take a loaf out of the window and leave the shop. She followed him out, shouting ‘Police’, and overtook him in the street, just as he was tucking into the bread. Grabbing his jacket, she challenged him and asked why he had stolen a loaf.

“Because I was hungry”.

P.C. Baker then arrived on the scene just as the thief took another mouthful, and an arrest was made.

In court a few days later the prisoner — a young man named John Scott — told a sorry story. He had recently been at Leeds where he was laid up with fever for two months, and then, with a couple of shillings in his pocket, he had left to make his way to Birmingham. Just over a week ago he was in Southwell, with only a couple of pence left, and travelled to Ilkeston where he arrived, soaked to the skin, and tried to get a bed at the lock-up.

On the Friday he had hardly anything to eat and wandered the streets that night before stealing the bread the following day, a crime which brought John some relief — as he was sentenced to a week in prison.

During a violent summer thunderstorm in June 1880 a large piece of stone from the parapet coping of the United Methodist Free Church School-room was dislodged and smashed through the roof of Thomas’s shop next door and into his bedroom. Fortunately it was early evening and the bedroom was vacant.

Lightning from the same storm entered a telegraph wire at the Market Place post office, lifting up the pavement outside the Old Harrow Inn where the current entered the ground. Damage was also caused to the roof of labourer John Lally’s house in Extension Street while a fire was started in the roof of the General Havelock Inn which also lost a chimney stack.

Perhaps one of the very few people out during the storm was Irishman ‘Deaf Jack’ who was unluckily knocked down, close to his lodgings in South Street by Richard Birch Daykin’s hansom cab, one of the very few vehicles out at the time. Being deaf, Jack had not heard the approach of the cab.

I remember two children, Frank and Fanny.

Fanny Eliza was born in 1852 and Frank alias Francis Samuel in 1858, though these were not the only other children in the family.

Fanny married lacemaker Charles Trott in August 1870 and went to live in Lenton while Frank, also a tailor, remained in Ilkeston.

Another in the family, two years younger than her sister Fanny, was Martha Ann who married needlemaker George Huskinson Bartlam in 1877 — we met briefly with George earlier in East Street.

After marriage they lived in Belper Street and Martha Ann died there, at number 41, in 1941.

Other surviving children were Herbert, Betsy and George.

—————————————————————–

Whatever happened to father George ?

Thomas Mather senior was the son of George and Elizabeth (nee Hirst) who were married on October 11th, 1800 at Nottingham. At that time George was working as an iron founder at Ilkeston. Their first child, Samuel, was born in 1801 while they were living in Cossall.

Their children, Mary and Ann were born in 1803 and 1804 respectively, at Derby.

George, Elizabeth, Thomas and Fanny were born between 1807 and 1813, in the Somercotes /Alfreton area.

And finally John was born in 1815 while the Mathers were at Eastwood, Nottinghamshire.

And then George disappears !! His wife Hannah can be found living in Ilkeston, without George, (on the 1851 census she is a widow) until she died and was buried in Ilkeston in 1853. But what became of George ?

John Daniel has been looking for his death for a very long time … He writes I believe that George Mather (husband of Hannah Hirst) died/was killed under dubious circumstances. I have a couple of newspaper articles (Derby Mercury and Nottingham Gazette) relating to a chap by the name of John Walker being charged with the ‘killing and slaying’ of George Mather in Somercotes in 1815 following an inquest held by the coroner of the time (George Gent). Other than this, I cannot find any follow on reports. It seems that John Walker was released ‘No Bill’ which apparently means insufficient evidence. I have tried to find out more about this case and what actually happened to George Mather but have hit a total blank. The County Records office tell me all old inquest documentation was pulped during WW2. I’m pretty convinced I have the same George Mather as he was an iron founder in Somercotes and didn’t father any children beyond 1815 (as I presume he was killed and slain!).

I think it will remain a mystery. I actually went to a meeting of the Somercotes Local History group once and specifically asked about a burial. I think they told me that the church in Somercotes hadn’t been built then.

Its a bit disappointing that the newspaper editors of the time didn’t give the full story. Reading the published articles in isolation wouldn’t mean very much i.e. no build up and no conclusion.

When I contacted the Records Office in Matlock they initially told me about the pulping in WW2 but said to try the coronor’s expenses claim as they sometimes give brief details of the inquest there. No joy!

This ‘George Mather’, killed in Somercotes in 1815, must have been buried somewhere, perhaps in Eastwood ?

John Daniel also writes of one of the illegitimate sons of Elizabeth Mather (nee Straw) ….

My great grandfather was Thomas Straw Mather who was the illegitimate son of Elizabeth Straw I believe.

His son, from his marriage to Sarah Beardsley, is Arthur who is my grandfather. Arthur died in 1955 before I was born.

My problem relates to the 1911 census for my grandparents – Arthur Mather and Elizabeth (Hartshorne) – which states that at the time of the census they had had 9 children, 4 living and 5 that had died. These children would be my Aunts and Uncles. Obviously, I know of the survivors but I had no idea of these deaths until seeing this census and, on and off for the last 5 or 6 years, have tried to establish who they where without total success.

I believe one was an illegitimate daughter named Florence (I don’t know for certain if this was Arthur’s daughter or Elizabeth’s but I have found a birth in 1896 with a surname of Hartshorn(e) which may or may not be her. I cannot locate a death record though. She appears on the 1901 census as a “Boarder” but then disappears. On this census, Arthur, Elizabeth and Florence are boarders at Elizabeth’s parents on Lord Haddon Road. Florence’s birth is stated as Ilkeston and, at the age of 5, would have been born before Arthur and Elizabeth married.

I have found two Mapperley Parish Church records which confirm that two of the unidentified birth/deaths were Catherine (1898) and Arthur Henry (1899/1900).

Can you help me identify who my remaining two Aunts/Uncles may be and shed any light on what happened to Florence.

I realise I could purchase copy birth certificates but I don’t know which to ask for as there are numerous Mather births within the period I am looking and don’t particularly want to speculate by buying numerous ones.

Following the 1911 census, Elizabeth and Arthur went on to have another 6 children – including my mother – of which another 3 died in infancy.

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Samuel Rice, grocer

“Mr. Rice opened the third as a grocer. The wall had been taken down and a large window put in the front room. He afterwards removed to the shop on south side of Park Road.”

Samuel Rice was the son of tailor Richard and Hannah (nee Meer) and worked as a stone miner.

Having previously lived in Bath Street, Chapel Street and Club Row, in the mid 1860’s he was living in the Market Place and a few years later was styled as a grocer.

By 1868 he was trading as such in Park Road.

In March 1860, still working as a miner, Samuel had married Mary Shaw, the daughter of labourer William and Mary (nee Mather). Thomas Mather was her uncle.

This Market Place shop had previously been occupied by William Robinson, needlemaker, before he moved to Extension Street. His son Samuel Robinson was born on the site of the future Town Hall on November 24th 1855 — a Hall where he was to preside as Mayor in 1898.

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

James “Jimmy” Johnson

Also in one of the cottages was joiner James ‘Jimmy’ Johnson, alias ‘’Squeeze-me’, and his family who lived there before moving to Ebenezer Terrace in the late 1850’s. He took part or ‘supervised’ several bonfire celebrations at November time on the Market Place. For eaxmple, in 1846 “ a large bonfire blazed in the Market Place. A tar tub, in flames, was rolled about the streets. Guns, pistols, and fireworks were discharged in rapid succession, to the satisfaction and delight of the inhabitants“. (Nottinghamshire Guardian)

————————————————————————————————————————————————-

We shall now walk across the Market Place and back to East Street to meet up with George Bunting and his neighbours.