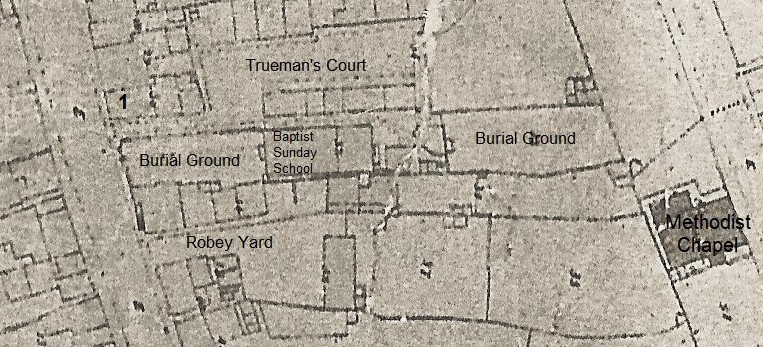

We shall pause at this point to consider the Baptist Chapel, wedged between Robey’s Yard and Trueman’s Court.

The map above is adapted from the 1866 Local Board map. The Baptist Sunday school was previously the Baptist Chapel until a new chapel was built in Queen Street. In 2023 that building still stands and is at present “the Latch Lifter” at 75 South Street.

1766-1820: Beginnings.

Adeline points out that “opposite the South Street Wesleyan Chapel was the Baptist Chapel. This was a very old place of worship.”

There is evidence that about the mid-eighteenth century there existed a small Baptist community in the Ilkeston area.

In May 1766 members of a General Baptist group, led by minister Nathaniel Pickering, came from Castle Donington, to preach at a dwelling house in Sawley but were prevented in their aim by the curate of the parish and a group of ‘drunken local rowdies’. Nathaniel was put in the stocks while his congregation was mobbed, their faces soiled with dirt thrown at them and with a bucket of blood from the butcher’s shop poured over them. “Hand bells were jingled in the streets and a merry peal was rung from the church steeple as if a glorious victory had been achieved by the Episcopalians over the Nonconformity intruder”. The same Baptist group then turned its attention to Dale Moor where the members achieved more success, such that a small meeting place was erected at Little Hallam in 1766. Some source suggests that there was a burial ground attached to this Little Hallam ‘sanctuary’ where some Ilkeston folk were buried. The Derby Mercury (May 29th, 1846) referred to this lost burial ground, “where a considerable number of persons had been buried“, and had been informed that the place had been ploughed over, “not a sign betokens where the dead rest“.

The successful work of this Baptist group led to two young churches being established firstly at South Street in Ilkeston (1784) — when the ‘chapel’ at Little Hallam was thus taken down — and later at Smalley (1790).

The Ilkeston chapel (below) was built on land sold to the chapel trustees by Joseph Simpson on August 6th 1784.

Edgar Waterhouse writes that the founders of the Chapel were Christopher Harrison and Thomas Woolley of Smalley, William Greasley of Stanton, John Stenson and Joseph Parkinson of Sawley, Vincent Wizar (or Wisser or Wizard or Whysall?), John Orchards and Joseph Harrison of Ilkeston, and John Bakewell and Thomas Dunnicliffe of Castle Donington.

At that time both Ilkeston and Smalley were branches of the church at Castle Donington and so, on special occasions members would walk to their ‘mother’ chapel in the morning and walk home again in the evening. Within a year however that situation was changed. The minute books of Ilkeston Baptist Church suggest that a year after its founding the Ilkeston church was now separated from Castle Donington.

“The Church at Ilkeston first established distinct from Castle Donington, May 22nd 1785”

Fifty three members attended this first Ilkeston church — 27 men and 26 women — coming from Cotmanhay, Shipley, Cossall, Sandiacre and Greasley, and because of the distance which some of them were travelling they met only in the afternoon. Mornings and evenings were reserved for outreach preaching, work that was shared with the Smalley group of Baptists, and was continued until 1822.

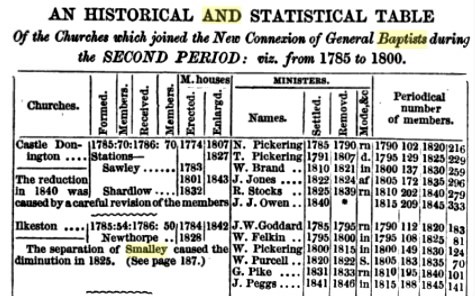

This accords (almost) with the detail in the table (below) discovered by Roger Purcell.

Pastors Goddard, Felkin and Pickering

From 1785 the Ilkeston pastor was John Waters Goddard who left the town in 1794 to reside at Kegworth and then Rothley where he died in 1812.

In the first five years of the church 72 adults were baptised, usually in the River Erewash at ‘Gallas Inne’, where large, inquisitive and sometimes boisterous audiences would gather. Doubtless in those days the Erewash was a ‘limpid stream‘ and not ‘first cousin to an open sewer’ as it was to become 100 years later.

The Baptists were vigorous and hardworking evangelists, accepting that they would have to travel many miles to spread their ministry, regularly going to places like Eastwood, Chilwell, Horsley, Coxbench and Heanor.

At such places they would build up contacts — hold meetings, visit homes, set up schools — and eventually and hopefully establish a chapel, an outpost to their mother church which might one day stand alone as an independent Baptist chapel. In this way the Ilkeston Baptists became linked to Smalley (1785), Derby (1790), Stanton (1791), Cotmanhay (1796), Mapperley (1798), Beeston (1802), Heanor (1812), as well as Stanley Common, Horsley, Awsworth, Newthorpe, Eastwood and Little Hallam.

Shortly after pastor John’s departure William Felkin was appointed in his place, holding office until October 1799 before he too departed for Kegworth where he died in 1824. He had lived in a cottage at the top of Bath Street, nearly opposite the end of East Street, which he purchased from Benjamin Goddard, a knitter, in January 1796 (writes Waterhouse) … Benjamin may have been the brother of John Waters Goddard.

Succeeding William Felkin as pastor in 1800 was William Pickering, a ‘zealous preacher‘ from Ashford/Bradwell in the peak disitrict of north Derbyshire, sometimes styled ‘The Apostle of the Peak‘. He ended his time in Ilkeston in 1815 at which time his salary appears to have been £52 p.a.

Strongly influenced by the Sunday School movement of Robert Raikes, it was William P. who had established the South Street Sunday school in 1807. This annex was added to the South Street building, nothing more than a lean-to on the south side of the Chapel, in Robey’s Yard, seating 80 scholars (now the site of the Health Centre). This was on land also previously owned by Joseph Simpson but later sold to wheelwright Ralph Shaw junior.

The trustees of the Chapel at this time were knitter Joseph Harrison, tailor William West, miners John Trueman and William Wrigley, all of Ilkeston, John Orchard of Little Hallam, knitter Christopher Harrison, brickmaker Thomas Woolley, and Samuel Cresswell all of Smalley, miner Stephen Barton of Greasley.

William Pickering died at Sneinton, Nottingham on February 19th, 1848, aged 81. He had been born in Castle Donington and baptised there at the age of 14. Leaving Ilkeston in 1815 he went to Staleybridge, Yorkshire and then, aged 55, went to oversee the Baptist Chapel in Stoney Street, Nottingham, remaining there for the rest of his life. He was buried at that chapel.

1820-1851: Growth.

Membership flourished such that by April 1822 the Ilkeston and Smalley churches felt sufficiently established to survive as independent communities and so agreed to a separation … property and debts were divided fairly and amicably between the them.

Before the establishment of the two independent churches, combined membership was nearly 150; in the year following the split the membership of the Ilkeston church alone was 123. After some internal problems and a fall in membership in the early 1830’s the church again recovered in the 1840’s, under two very successful ministers….

…… James Peggs (August 1841-1846) .. He arrived from the General Baptist Chapel at Bourn, Lincolnshire after about seven years service there, and had been a missionary at Orissa in India where apparently the misery and deprivation he had to witness there forced him to return to England. Not the most gifted pulpit orator he was a very amusing platform speaker and a self-denying devoted Christian. At the end of February 1846 he left for Burton upon Trent.

……. Caleb Springthorpe (August 1847-1853) … arriving in Ilkeston from the Baptist College in Leicester, greatly appreciated by the congregation whilst serving in the town, and sorely missed at his departure for West Yorkshire. On December 28th, 1848 he had married Mary Ann Yates, eldest daughter of Leicester stone-mason Joseph at the Baptist Chapel in Dover Street, Leicester.

These Ilkeston Baptists were Arminian in theology — basing their beliefs on the doctrine of the Dutch theologian Jacobus Arminius of ‘free will’ and universal salvation. Thus they were General Baptists holding that the death of Christ meant redemption for everyone.

(In contrast, Particular or Calvinist Baptists were influenced by the theology of John Calvin, and believed in ‘limited atonement’, that Christ had died to save only particular persons who were predestined to be saved, those whom God had chosen.)

The effectiveness of the Baptist publicity can be gauged from the Minute books of the Church…

“Lord’s Day, May 1, 1841. Seven friends were baptised in the Erewash. About 1500 spectators…who behaved very orderly”

“Lord’s Day, September 19, 1841. Several (four) were baptised in the Erewash. Mr. Pegge preached in the chapel and addressed the audience by the waterside. Probably 1200 persons were present”. This ceremony had been organised by pastor James Peggs who had very recently arrived at Ilkeston.

Membership was growing….113 in 1842, 141 in 1845, up to 181 by 1851.

Another result of the growth was that in 1842 the Ilkeston Baptist church building was extended, and a gallery added. The chapel reopened in September of 1842 with public dinners, teas and suppers being offered. Collections totalling £26 were taken.

New members had to travel to the Erewash Canal at Gallows Inn to be baptised but this ceased in 1848 when the comfort of a baptistry at the South Street chapel was introduced.

And on July 23rd, 1843 “a neat little chapel was opened by the Baptists at Kensington. No expense had been incurred”

Public baptisms continued, as in December 1846 when nine new converts were immersed in the Erewash canal — after the ice had been broken !!! As usual the event attracted a large crowd.

In the 1851 Religious Census the South Street chapel is listed as having accommodation for 300 persons (104 free and 196 other).

Sunday morning attendance was 91, with a Sunday School of 107, an afternoon School of 122 and an evening congregation of 204.

Baptist minister Caleb Springthorpe of Lawn Cottage supplied these figures. He left Ilkeston to take up a post at Heptonstall Slack General Baptist Chapel, West Yorkshire, in August 1853.

‘Free’ sittings were those which were not permanently rented to particular individuals – anyone could have access to them. ‘Other’ sittings were those which were let or had become private property.

Here is a photo of the old chapel taken from Robey’s Yard. (North East Midland Photographic Record)

The 1850’s: T R Stevenson and a new chapel.

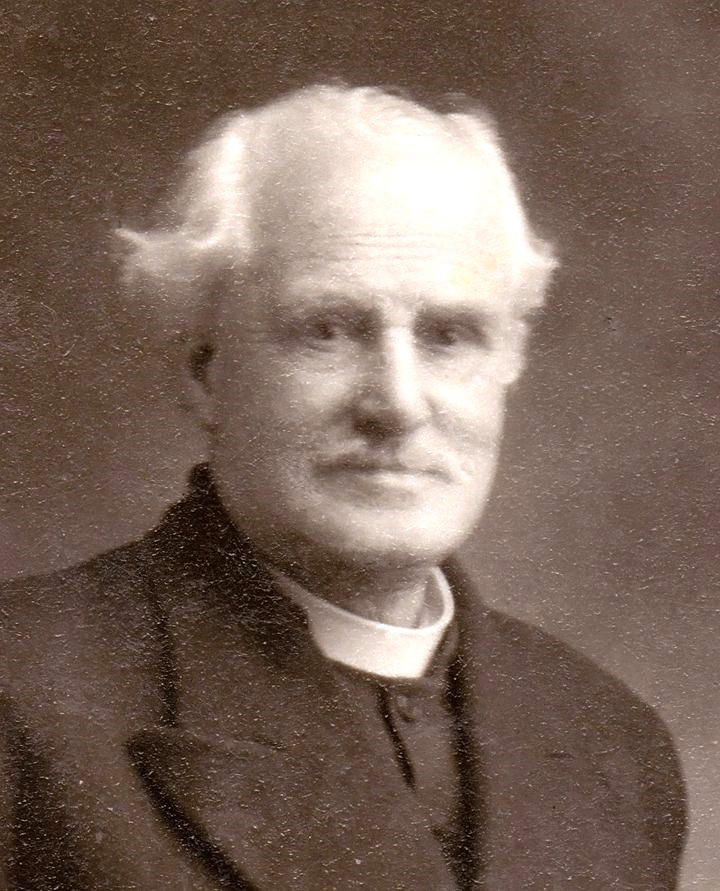

Succeeding Caleb Springthorpe as minister in 1854 was Thomas Roberts Stevenson, “a young man fresh from college, sanguine, earnest, genuine, and a very interesting preacher … with genial humour, sparkling wit, amiable temper, … downright honesty, .. fearless advocacy of the claims of the poor, and .. thorough sympathy with the working classes”. (IA 1881 An Old Resident’s letter*)

Also a man of great energy and innovation he introduced evening observation of the Lord’s Supper, standing up for singing and prayers, the practice of new tunes by choir and congregation, the singing of hymns in their entirety – and a new harmonium, in 1855!!

He was in office in 1857 when the continued growing numbers at the chapel finally necessitated a new building. By that year it was clear that the accommodation provided by the South Street Meeting House was inadequate to fulfil the needs of Ilkeston’s Baptist community

(*N.B. Ilkeston had no shortage of ‘Old Residents’ eager to share their views with the wider public. The Advertiser’s Old Resident should not be confused with the one writing to the Pioneer and cited elsewhere … see Sources. Don’t you just love pseudonyms!!).

Adeline points out that “when the new chapel was built in Queen Street, the congregation removed to it, and the old chapel was used for the Sunday School.”

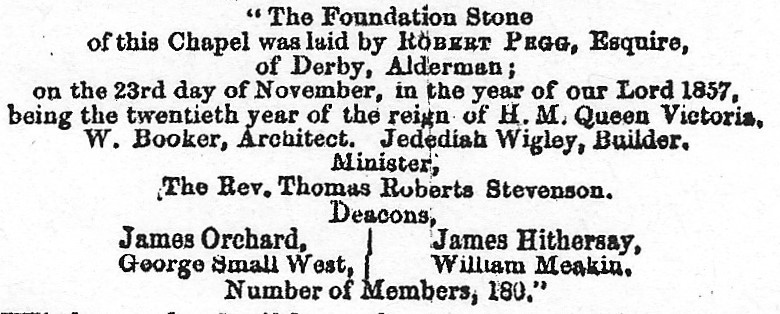

The corner stone of the new Baptist Chapel in Queen Street (above) was laid at half-past three on a beautifully fine Monday afternoon, November 23rd 1857, a ceremony performed by Alderman Robert Pegg of Derby and witnessed by representatives from nearly all of Ilkeston’s dissenting churches as well as from the Established Church. Under the stone was placed a document recording the event, the names of the builder and designer of the church, some of its officers including deacons James Orchard, James Hithersay, George Small West and William Meakin, and the size of its membership (180).

An hour later about 200 guests were tucking into a public tea in the South Street chapel to celebrate the occasion.

A public meeting at the same place followed in the early evening, led by the Rev. Thomas Roberts Stevenson.

“Most certainly the whole proceedings connected with the laying of the corner-stone passed off with great éclat”.

Jedediah Wigley had been awarded the contract to build the new chapel, which was completed in 1858 at a cost £1400, and seated 400.

The opening ceremony took place on Tuesday, June 22nd, 1858. William Henry Booker of Nottingham, the architect of the building would not have been pleased with some descriptions of his creation. For example, the Pioneer records – 23 years after the chapel’s opening — that “of the many places of worship which have sprung up in our town, this is certainly the least attractive; some people think it positively ugly and repellent, and we have heard it likened to an engine shed. Perhaps the greatest defect of the building (it has many) is its bad acoustics; for a disagreeable echo makes it an almost painful task to listen to even the most accomplished speakers”. (April 28th 1881)

The first baptisms in the new church — on September 20th 1858 — were those of Frederick Cook, grocer of Awsworth Road, his wife Mary (nee Hartshorn), and William Wright Turner, grocer’s assistant of Regent Street.

Frederick was elected a deacon in 1862 and William became Church Secretary in 1863.

After the opening of the new church the old South Street building was kept as a children’s Sunday School, as Adeline suggests, and a period of continued growth led to the school’s expansion in 1866.

Adeline remembers that “the Rev. Thomas Stevenson was a Pastor at the new chapel in Queen Street.

He was a real live wire, but the people were too apathetic, and soon the Rev. Thomas removed to a sphere where his energies were more appreciated”

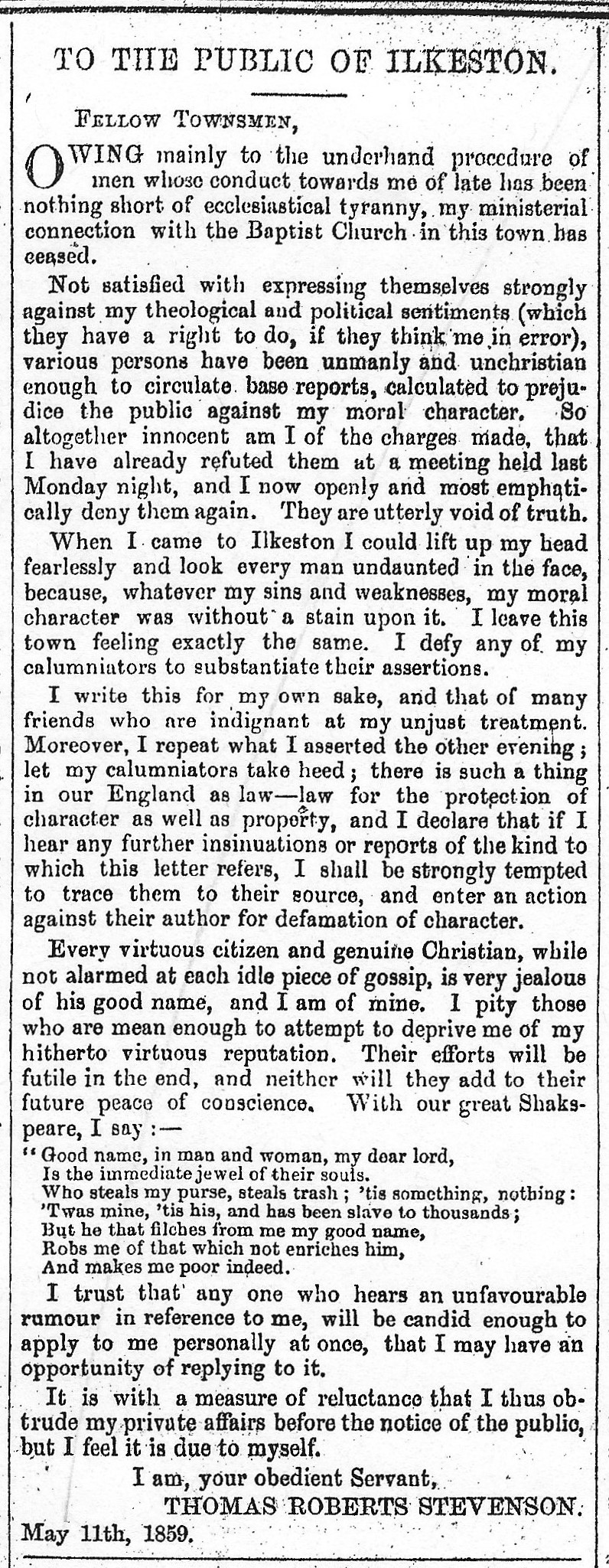

The building of the new chapel left the Baptist community with a large debt to service and thus a period of severe and prolonged pay restraint was introduced. Consequently when the Rev. Stevenson requested a salary increase in early 1859 it was promptly rejected. This may had led to his subsequent clash — in May 1859 — with certain influential members of the Baptist Church and then his expulsion, an action which divided opinion within the community.

A meeting at the Old Baptist Chapel was organised at which his supporters showed boisterous support for him. Several guest speakers gave testimony to his character and qualities.

For example the Rev. James Stevenson – no relation!! — from Nottingham described Thomas as “an independent thinker…. he borrowed not his opinions, nor his faith, from others….he waited not for what great men had to say, but having made up his mind, he stated his opinions roundly and boldly, in hard round English words that hit”.

To avoid a split in the church Thomas was determined to leave the town. But not before he penned a caustic letter to be published in the Pioneer. (right)

A gift of a purse containing 15 guineas, ‘subscribed by scores of the working classes’ was presented to the pastor before his departure.

Thomas left to go to a church in Burnley; he later moved on to Luton, Colombo (for seven years), and back to St. Mary’s Gate Baptist Chapel, Derby.

1860-1881: Comings and Goings … and Divisions.

“The Rev. William Anderson, a Scotsman, was Pastor for some time.

His sister, Miss Anderson, became the senior Mr. James Hithersay’s second wife.”

A short period of upheaval at the church was followed by the appointment of William Milroy Anderson of Hawick to the pastorate in August 1862, commencing his duties on the first Sunday in September. His sister was Helen.

The Hawick Advertiser reported that Mr. Anderson had been a pastor at the Baptist Church there for nearly ten years “and his constant and untiring exertions for good have for him the high esteem not only of those belonging to his congregation, but of all classes of the community ….quiet and unassuming in his deportment, he was at all times ready to aid and to forward any movement in which the welfare of his fellow townsmen was concerned…..we regret the loss to our own community of so valuable a member ….just before his leaving Hawick he was presented with a purse containing ten sovereigns”.

“With no brilliant preaching power .. he was nevertheless a thorough Christian gentleman, a most hardworking and indefatigable pastor, visiting the homes of the people with a loving sympathy..” (an Old Resident’s letter IA 1881)

However two years later, William’s resignation from the church and departure from Ilkeston in July 1864 was also occasioned by an inability to increase his salary.

“But some time after, differences occurred among the congregation, resulting in many returning to the old chapel, where services were resumed.”

After a brief ‘inter-regnum’ Pastor John Stevenson of Derby (1866-1872) then came to Ilkeston, having served at Borough Road Church, London, and St. Mary’s Gate Church in Derby … and “a more loving spirit, a more amiable temper, a more genial friend and companion, a more self-sacrificing, Christ-like man never laboured in the midst of the people” (Old Resident IA 1881)

Having begun to restore the church’s finances mainly ‘through self-denying liberality’ Pastor John was faced once more with divisions within the church and ‘sought another field for usefulness’.

In his place — after another brief pastor-less period — stepped John Wild of Hucknall (1873-1877) “a man of stern integrity, and much devotedness … a pulpit orator, a thorough, powerful preacher… but too tame” to reconcile the forces of division. (Old Resident again.)

There followed students from the Baptist College, Chilwell (1877-1879), serving at Ilkeston before the arrival in December 1879 of Arthur Charles Perriam (1879-1884), “a man of refinement and ability” but whose countenance “indicated habitual melancholy. He was a man of lovable disposition and a good preacher, but his nature was too highly-strung and sensitive to stand the wear and tear associated with the pastorate of a poor and unbeneficed church”. (RBH)

Arthur Charles arrived with his wife Marianne Roslina (nee Scammell), daughter of London bootmaker Richard and Elizabeth, and whom he had married in 1868. However a year after their arrival — on November 13th 1880 — Marianne died at their Stanton Road home, aged 34. “Originally an apprentice to tailoring in London, Arthur Charles experienced a ‘call’ to the ministry, and for a number of years officiated at the old place of worship off South Street. The salary was very small, and the position by no means a bed of roses. It must indeed have been a struggle for him to maintain a delicate wife and several young children, and at the same time keep up the essential appearance of respectability required by his profession mon the stipend he received.” (RBH)

For a while the Baptist Chapel flourished.

In April 1881, at the anniversary of its Sunday School, a large new area between the Stage and the auditorium was filled with 120 scholars singing with “precision and good taste, a choice selection of hymns”.

The chapel was filled to capacity such that many members of the public were left outside.

Stalwart of the Chapel, James Hithersay, offered a gift of £50 to help erect a much-needed gallery – an offer gratefully accepted – and there followed much effort to add to that sum, to reach a total of £400, about enough to convert it into a “neat and commodious place of worship”.

1881-1884: Split.

The personality and style of management of the new pastor were not to everyone’s liking.

Strains between Arthur Charles and the Church deacons soon appeared, and in September 1881 53 members of the congregation (including two deacons – one who had served for 30 years, the other for 20 years) seceded from the church and were granted permission by the Trustees to meet at the old South Street Chapel.

“The secessionists are for the most part the influential members of the place”.

“A number of the teachers and scholars in the Sunday-school threw in their lot with the secessionists, and as the chapel school is conducted (in the old schoolroom), the spectacle has been presented of a divided school, inasmuch as a number stop for worship in the schoolroom, whilst the others, (with the pastor) walk in procession to the Baptist Chapel”. (IP)

A week after this report it was arranged that the Sunday School would meet at the Queen Street Chapel.

An appointed Board of Arbitration saw this split as a brief temporary arrangement — one that was to last for nearly 40 years!

At the end of October 1881 the Board gave its judgment;

“The arbitrators … expressed their pleasure at the fact that no charges had been preferred against the minister of unsoundness in doctrine or general unacceptableness in preaching or pastoral labour. The grievances alleged related chiefly to the differences of opinion on church management or hasty reflections on individuals. They gave it as their opinion that a proper amount of Christian patience and charity at an early stage of the unhappy difference would have prevented the secession which appeared to be impending. Believing that no impardonable offence had been committed on either side they exhorted the two parties to mutual acknowledgment and forgiveness. When however it appeared that an immediate reconciliation was impossible they recommended that for a season the two parties should work and worship separately.

“It was advised that for the future Mr. Perriam and his friends should hold their Sunday services and conduct their Sunday school in Queen-street, and that the seceders should worship and conduct their school in the old chapel, in South-street. It was advised that the church in Queen-street should amicably dismiss the members meeting in South-street in order to (facilitate) the formation of a new General Baptist Church.

“(The arbitrators) considered Mr. Perriam still worthy of the affection and confidence both of his own friends and of the General Baptists denomination”.

The great majority of the church congregation agreed to accept these recommendations and Mr. Perriam now thought the dispute effectively settled!!

From 1882 Ilkeston had two Baptist chapels when the South Street premises were sold to the seceders for £200. With this money, swelled by public contributions, the Queen Street Church added a new gallery and new schoolrooms at the west end of its building, while its seating was increased to 500 although its membership numbers had plunged since the secession. The building work was entrusted to Frederick Shaw of the Manor House at an estimated cost of £1000. (Robert Argile of Ripley was the architect).

And a third chapel was added (below), built on Norman Street, Cotmanhay in 1882. Can you see how similar its fascade is, to the original South Street chapel (at the top) ? I’m afraid I know nothing of this chapel at the moment. Can anyone help ?

In 1883 Arthur Charles Perriam married his second wife Jane Ann Weatherhogg, daughter of Granby Street pawnbroker Thomas and Phoebe (nee Foster).

The Perriam couple left Queen Street in August 1884 when Arthur Charles took up a pastorate at Dewsbury, Yorkshire.

When he had arrived at Ilkeston the debt of the Baptist Chapel was £200 which the alterations he had undertaken raised to over £1400.

At his departure that debt had been reduced by more than £800.

In May 1883 the Advertiser recorded the marriage of Elias Barnes and Sarah Briggs of the Potteries at the old Baptist Chapel in South Street — in fact the bride was Annie Briggs.

The newspaper included the detail that the chapel was 100 years old and that this was the first marriage there for 99 years.

In April 1884 services were held at the Old Baptist Chapel in South Street to celebrate its centenary of public worship. The collections taken were to help fund a new roof and ‘other needful repairs’.

1884: Young Charles Aked arrives … and soon leaves

“The Rev. Chas. Aked, afterwards Dr. Aked, was a Pastor at Queen Street Chapel. He ultimately went to America, where he became very popular. He married Mr. Jas. Hithersay’s granddaughter.”

In July 1884 Charles Frederick Aked, ‘a lanky, hollow-cheeked, impetuous youth’, arrived at the Queen Street Chapel from the Nottingham Baptist College, to hold a student pastorate at Ilkeston for a year.

He was born in Nottingham in 1864, the son of Charles Aked, hosier and later a licensed victualler trading at the Poplar Tree Inn, and Ann (nee Minion). Charles was first employed in Nottingham as a junior clerk in a coal merchant’s office. However he later trained as an auctioneer and was articled to a Nottingham auctioneer who was also sheriff’s officer. Apparantly this involved ‘some exciting and distressing experiences in the way of execution of warrants from the sheriff’. Then becoming an auctioneer, for a few years in the early 1880’s he had traded as such in London Road, Derby, in the employ of the sherriff’s office for Derbyshire, often selling off seized goods.

Charles then toyed with the idea of emigrating to New Zealand before deciding to train for the Baptist ministry. As a boy he had been brought up within ‘the Church of Christ’, was a Sunday School scholar and a teacher at the meeting house in Sherwood Street, Nottingham, where he had been baptised. And it was from that city that Charles came, at first as a visiting speaker, to Ilkeston.

In his time at Ilkeston Charles Frederick was wooing Annie Hithersay, daughter of (the late) Nottingham Road grocer James and Mary (nee Whitehead).

On one occasion, when scheduled to preach at Kimberley, Charles chose instead to spend the Sunday evening with Annie and secured the services of a young Arthur Copley to act as his substitute preacher. It would seem that Charles impressed Annie — the couple wed in 1886.

Cyril Hargreaves describes Charles as “a fiery and enthusiastic speaker with unashamedly Radical views, who lived to become one of the greatest preachers of his day’” while Charles’s brother-in law, Richard Benjamin Hithersay, saw him as “bold and aggressive, and not at all calculated to be disturbed by chapel squabbles or adverse criticism from any quarter. — His vigorous personality and obvious intellectual power attracted the Queen Street congregation. It was not long before he made his mark in the town as a preacher of exceptional force”. However “he was by no means a modest flower, content either ‘to blush unseen or waste his sweetness on the desert air’ of Ilkeston at one hundred pounds per annum”

Thus after his marriage he continued his progress, onwards and upwards.

Leaving Ilkeston for a short-lived pastorate at Syston, Leicestershire (1886-1888), Charles Frederick was then appointed to the Baptist Church at St. Helens, Lancashire (1888-1890). It was there, in August 1890, that a ‘curious incident’ occurred — perhaps illustrative of the character of the preacher at this time. Accompanied by his nephew, Albert Edward Newton (of Lincoln Grammar School), he was taking a stroll in the nearby countryside and aimed for a spot of fishing at Eccleston Mere.

Photo by Michael Heavey (2006)

As they came to Eccleston Mill dam, they saw a man’s clothing draped over a fence. However, as there was not one soul around, they assumed something might be amiss, and peering into the deep waters of the dam, something ‘very white’ could be seen deep down. Charles Frederick quickly disrobed and, accompanied by a newly-arrived local, he dived into the water — what they found was the dead body of a young man Thomas Jameston, who, it transpired, had lived about half a mile away. Had he drowned while taking a very early morning bath ?

The cleric next arrived at Pembroke Street Chapel, Liverpool at the end of September 1890 when his first morning sermon was on ‘The Good Old Days‘. His evening sermon was entitled ‘The Parliament of Labour: its Power and Promise’ to which ‘trades unionist were cordially invited’.

He had opinions on many issues of the day and was not unafraid to voice them; he spoke in favour of Oscar Wilde, against the Second Boer War, in favour of the complete secularisation of state and rate-aided schools, and against intoxicating liquor, ‘Britain’s worst curse’.

May 26th, 1897 was a “red letter day” in the history of Queen Street Baptist Chapel, according to the local press — the day when the Rev. Aked paid a return visit to his former chapel, to deliver a sermon in the afternoon and a lecture in the evening. The latter event saw the venue crowded with a “highly intelligent audience” whose members listened, in rapt attention for an hour and a half to this “youthful, energetic and intellectually brilliant pastor“.

Less than a year later Charles Frederick returned once more to Ilkeston, this time to preach and deliver a lecture on “the call of the 20th Century” in the newly opened Wesleyan Methodist church in Bath Street. Amongst his large audience was Ilkeston’s M.P. Sir Walter Foster. And then in December 1898 he was back at the same venue delivering his ‘popular lecture‘ entitled “The Strongest Man on Earth” and spoke for one and a half hours, without hesitation or any notes, quoting both Socrates and Henrik Ibsen.

The Temple College, Pennsylvania conferred a degree — D.D. — upon him, an act which provoked some criticism among contemporaries and led Charles in May 1906 to publicly deny the ‘honour’, a degree which ‘he ought never to have accepted’.

The Derby Daily Telegraph commented upon Charles’s action: ‘The interesting cleric whom we are accustomed to know as ‘The Rev. Charles F. Aked, D.D.’ is now to be known as ‘Mr. Aked’. He voluntarily submits to a process of decapitation and curtailment. He wishes his friends to drop the ‘D.D.’ and the prefix ‘Rev.’ as well. Evidently the ungenerous discussion of .. the degree has annoyed him and he says ‘the time has come for him to repudiate the degree, …. it was conferred upon him in recognition of efficient public work as a Minister of the Gospel by … the biggest Baptist institution on the face of the earth’.

Subsequently Charles accepted the invitation to be pastor of ‘the Millionaires’ Church’ of the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church (known as the Rockefeller Church, heavily endowed by John D. Rockefeller, ‘the richest man in the world’.) in New York in 1906, with a home on that avenue and ‘a fabulous number of dollars per annum’.

His salary was a reported £2000 per annum.

By 1912 Charles had moved on to the First Congregational Church in San Francisco and in 1913 became a full-fledged American citizen. He later moved on to Kansa City and finally to All Souls’ Church, Los Angeles.

In August 1923 Charles returned from the United States to visit Ilkeston with his wife Ann and to receive a civic welcome in the town.

The Pioneer revealed that he was the author of numerous religious works and hymns and that “in America competent critics have rated him as the greatest living pulpit orator”.

Also by that time he had received the degree of Doctor of Laws (1913) from the University of Nevada, held a triple doctorate of Divinity, and had been minister of the First Congregational Churches in Kansas City and San Francisco.

On the return journey, on board the Empress of France, Charles preached before the Prince of Wales — who was travelling incognito as ‘Lord Renfrew’. The Manchester Guardian was sure that ‘Baron Renfrew’ would have heard a good sermon ‘for Dr. Aked would have to try very hard to preach a bad one’.

In 1933 Richard Benjamin Hithersay recounted his most recent meeting with brother-in-law Charles.

“Two or three years ago I lunched with the ‘Rev. Dr.’ and Mrs. Aked at a London hotel, and I left the hotel with the strong impression of the truth of the age-old saying ‘Vanitas vanitatum, omnia vanitas est’. (Vanity, vanity, everything is vanity.) Years of indifferent health, accompanied by a gradual failure of sight which the most famous oculists in America seemed powerless to arrest, and which was naturally a source of acute and constant anxiety, had combined to effect a striking metamorphosis in the one-time buoyant, brilliant and ambitious young preacher”.

Charles Frederick died in Los Angeles in August 1941, aged 76 and was buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale. (www.findagrave.com)

Annie Aked (nee Hithersay) had died in June 1934 and was interred at the same place.

the 1890s: the church in flux

In 1894 the Queen Street Baptists co-operated with the Heanor Derby Road Baptist Chapel with a view to securing the oversight of a regular pastor for the two churches. As a result the Rev.George Dean Jeffcoat of the Midland Baptist College in Nottingham was appointed.

April 1896 .. and time to have the Queen Street chapel thoroughly cleaned. But how to pay for it ?? The answer of course was to organise a bazaar. And so it was …. held in the adjacent schoolroom, over two days,and organised by the Rev. Jeffcoat. There was a “Church stall”, a “Sunday School” stall, a “Band of Hope” stall, refreshments and ice cream, a book stall, an art exhibition, a bran tub and a weighing machine, and a galvanic battery.

Adeline then continues: “After some years it was decided to close the old chapel, and for many years it was deserted. But about 1900 or thereabouts, the old chapel was put in order, and services were resumed. I went into the chapel in 1914 and was very pleased to see how nicely it had been restored to its former state, and was shown the different seats where people sat who had returned to their first love.”

Membership at the Queen Street chapel continued to fall or remain small but this was reversed by the arrival, in 1898, of Arthur Copley as lay pastor, whose work once again began to fill the church and eventually, in 1920, led to the unification, once more, of the Ilkeston Baptists. When Arthur arrived the spirit of the Baptists was at a very low ebb, and they were finding it impossible to maintain a minister. Services were sparsely attended and empty pews preponderated. The new arrival sought to turn around the chapel’s fortunes and did so with untiring, arduous and self-sacrificing effort. Within two years a remarkable improvement in the Baptist fortunes could be clearly seen.

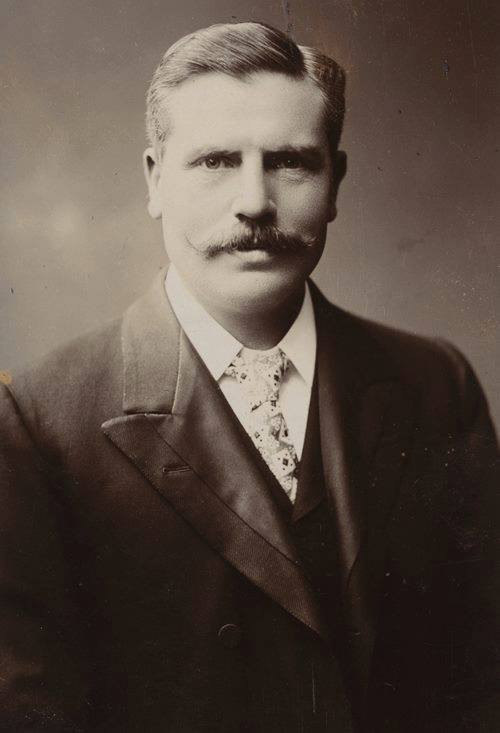

Rev. Arthur Copley (1862-1938)

“Rev. Copley took up the ministry at Queen Street as the church was adopting what it called a ‘Forward Movement’ of radical change in the work of the church and during his forty year ministry this new approach found its expression. More music was used in services and an organ was purchased in 1917. The work of the church appears to have been ‘opened up’; various practical evening classes were set up, a ‘Men’s Own’ formed in 1903 and clubs for running and football established. The popular May Festival became an annual feature in the Church calendar”.

When Arthur Copley accepted the permanent pastorate at the chapel in December 1899, he was joined in a public tea and “housewarming party” by Elijah Higgitt, one-time tailor and hairdresser of Bath Street, and a long-time member of the chapel, who had retired to Kegworth. In the short time that Arthur had been at the chapel, membership had increased from 80 to 400.

Sunday, November 25th, 1900 was Arthur’s 38th birthday, and to mark the occasion and thank the pastor for his endeavours in ‘rescuing’ the chapel, a silver purse filled with gold was presented to him at a special tea, organised for the following day. Arthur and the guests could also tuck into to a sumptuous birthday cake (two tiers !!) donated by William and May Lamb of the Lord Haddon Café in Bath Street.

If you wish to follow the history of the chapel after this, I would recommend you start with the pamphlet, “Two Hundred Years of Baptist Witness in Ilkeston” (from which the previous paragraph was taken)

———————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Before we continue our walk along South Street, towards the Market Place, we will pause to reflect upon the life of William Felkin, son of the Baptist Minister mentioned above …

… or if you are feeling thirsty, we can visit the neighbour of the old Baptist Chapel, the Prince of Wales … but not the one to whom Charles Aked preached in 1923.