1849-1930

Using a batch of documents kindly offered from the personal archive of Jim Beardsley, let’s have a look at how some new housing was developed in Station Road, when and by whom. Like so many property deals at this time, conducted without estate agents, you will see that land changed hands regularly, and it is often difficult to keep up with its ownership. Many loans were involved, of small and large amounts, a few houses were erected and at least one street was constructed during this time.

————————————————————————————————

1865: Welcome to Robert Knighton Skeavington

Robert Skeavington was a prosperous Cotmanhay farmer who died on November 13th 1849. In his will, he left a number of monetary bequests to his illegitimate and legitimate daughters, all born to Mary Knighton — whom he had married in September 1825, and to whom he left all his real estate, so long as she lived, or did not remarry. Mary did not remarry, and died on May 24th 1861, at which point the estate passed to the illegitimate and only son of Mary and Robert, named Robert Knighton or Robert Knighton Skeavington (born in 1822).

On April 18th 1865, Robert Knighton Skeavington paid a fee of £412 at Ilkeston’s Manorial Court to enfranchise part of his inherited estate. It was called Barn Close or Pithills, and occupied about 4¼ acres.

Have you any idea where it was ? …. a clue: why has it been included here ?!

On the day of enfranchisement, Robert also mortgaged this property for £1800 with Alice Emery, a widow living in Derby … she was born Alice George in Arnold, Nottinghamshire, in 1798, her paternal grandmother being an Ilkeston Skeavington, and probably a relative of Robert (although I haven’t yet quite worked out the relationship)

Alice died on November 17th 1874 and in July of the following year Robert paid £2100 17s 3d to the executors of her will, being the principal plus interest still outstanding on the mortgage. The property was thus fully back in his hands.

This was not the end of Robert’s financial business however. At the Ilkeston Court Baron on April 18th 1876, he surrendered some of his inherited copyhold property to Matthew Hall of Granby, Nottinghamshire, for £1500, borrowing a further £150 from the same source a little while later. And by October 1879 all that money was still owed. At this time, to act as security, Robert’s Barn Close was made over to Matthew Hall. Because of the sale of some parts of it, the size of the Close had by that time been reduced by almost an acre.

By April 1881 Robert had been unable to pay his debts and so filed for bankruptcy … and a month later the Bankruptcy Court’s liquidator began selling off Robert’s assets which of course included his real estate.

——————————————————————————————————-

1881: Welcome to Charles Hiram Gregory

Robert Knighton Skeavington’s land subsequently passed through a series of convoluted financial agreements and various pairs of hands until Charles Hiram Gregory acquired part of it on December 14th 1881.

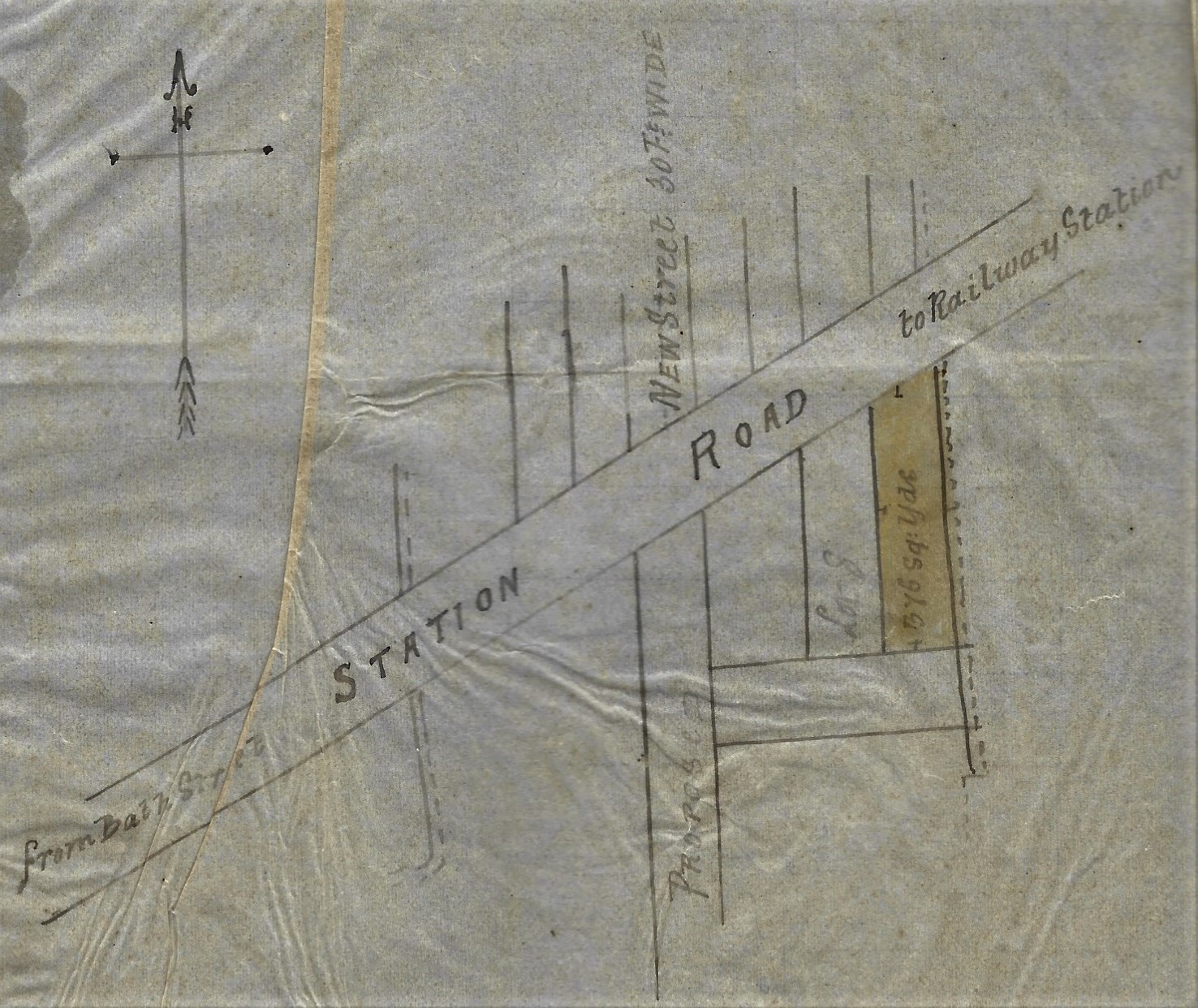

At this time a diagram of the area acquired by Charles Hiram was drawn on tracing paper (on the left).

Part of the area was coloured yellow and was described as on the south side of Station Road and abutting that road, and being on the east side of a plot of land marked Lot 8 on the plan.

It was approximately 376 square yards in area

I hope you can make out these features.

You will also see that there is a ‘proposed new street 30 feet wide‘ which is shown crossing Station Road … have you any idea where we are now ??

——————————————————————————————————————-

1882: Welcome to Frederick Henshaw

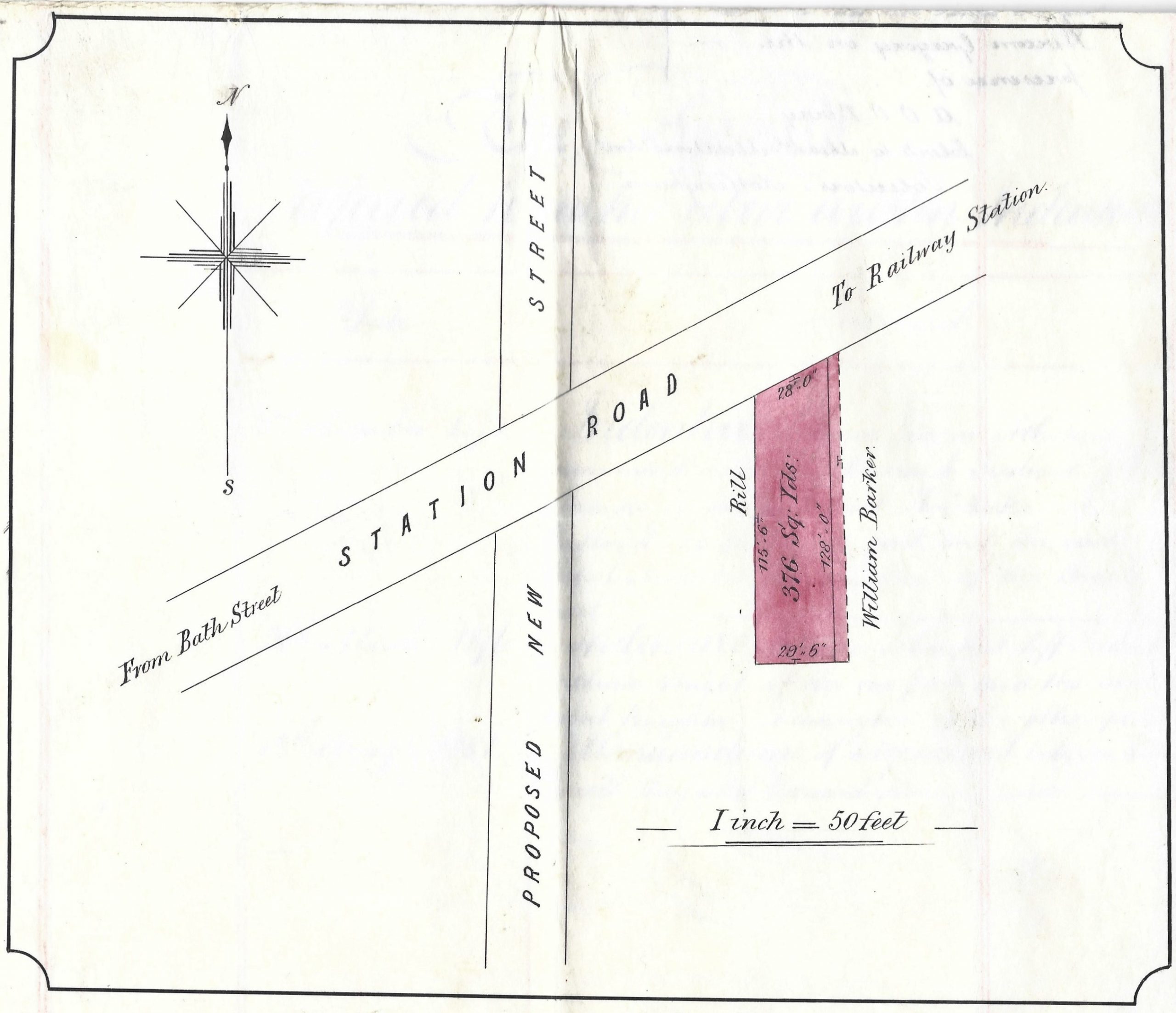

On March 17th 1882, for £3600 and interest, Charles Hiram Gregory mortgaged most of this land to Henry Abel Smith, a banker of Nottingham, who, on November 8th of the same year, conveyed the yellow-shaded portion over to Frederick Henshaw for £56 8s. This portion was still about 376 square yards and shown on the plan below, with its boundary ‘neighbours’.

Plan appearing in a Conveyance Agreement between Frederick Henshaw and Charles Hiram Gregory and his Mortgagee (Henry Abel Smith), November 8th 1882

On acquiring the land Frederick immediately started building two houses there, and four weeks later arranged a mortgage of £220 for the two premises with the Rutland Lodge Friendly Society, (based at the King’s Head), through the Society’s two trustees, William Ball and John Mellor. After this, Frederick paid the interest on time, though the principal remained outstanding.

The two houses were later numbered as 105 and 106 Station Road.

——————————————————————————————————

1886: Welcome to King Street

Frederick Henshaw acquired further land in this area, built a further three houses here, and on August 24th 1886, took out another mortgage with the same Friendly Society, this time for £80. (Note that trustee William Ball had died on February 2nd of that year and his post as trustee was taken by John Moss)

The proposed new road, shown in the plan above, had now been constructed, 30 feet wide, and was called — or was to be called — King Street. And it now formed the eastern boundary of Frederick’s new parcel of land, which measured 295 square yards. The remaining boundaries were occupied by land belonging to John Hallam, Enoch Waters and Thomas Smith.

On September 14th 1893 a further £70 was raised by Frederick, from the same Friendly Society and on the same terms (John Mellor had died on November 30th 1892 and had thus been replaced as trustee by John Ball). And then a further sum of £25 was raised via solicitor Frederic Cattle on May 19th 1896.

—————————————————————————————————–

1897: Welcome to Walter Bonsall

On September 25th 1897 Frederick was able to pay off all the money owed by him, and this was signed off by the Trustees of Rutland Lodge Friendly Society — by then they were John Ball, Robert Wood and Charles Maltby.

Two days later Frederick sold his two houses in Station Road to Walter Bonsall, for £450. It was still 376 square yards in area but now with new neighbours — it was bounded on the south by the land of Isaac Fox, on the east by land formerly of William Barker but now of William Holbrook, on the west by the land of William Rice, and on the north by Station Road. In the two houses, with their yards, gardens, greenhouses and outbuildings, lived Frederick Henshaw and Joseph Rice, the latter having the ‘lock-up sale shop‘ of Mrs Ann Barnes at its front.

————————————————————————————————————

1898: Welcome to Thomas Samuel Sisson

And then — on August 11th 1898 — for £300 plus interest, Walter Bonsall mortgaged the same Station Road property, together with his cottage at the rear of the New Inn in Bath Street which Walter had inherited recently from his father James. This cottage had a frontage to Wilmot Street. (You can see a detailed plan of this Wilmot Street property here) The mortgagee was Thomas Samuel Sisson of 5 Heanor Road, and a couple of months later, a further £100 was added to the original mortgage agreement.

————————————————————————————————————–

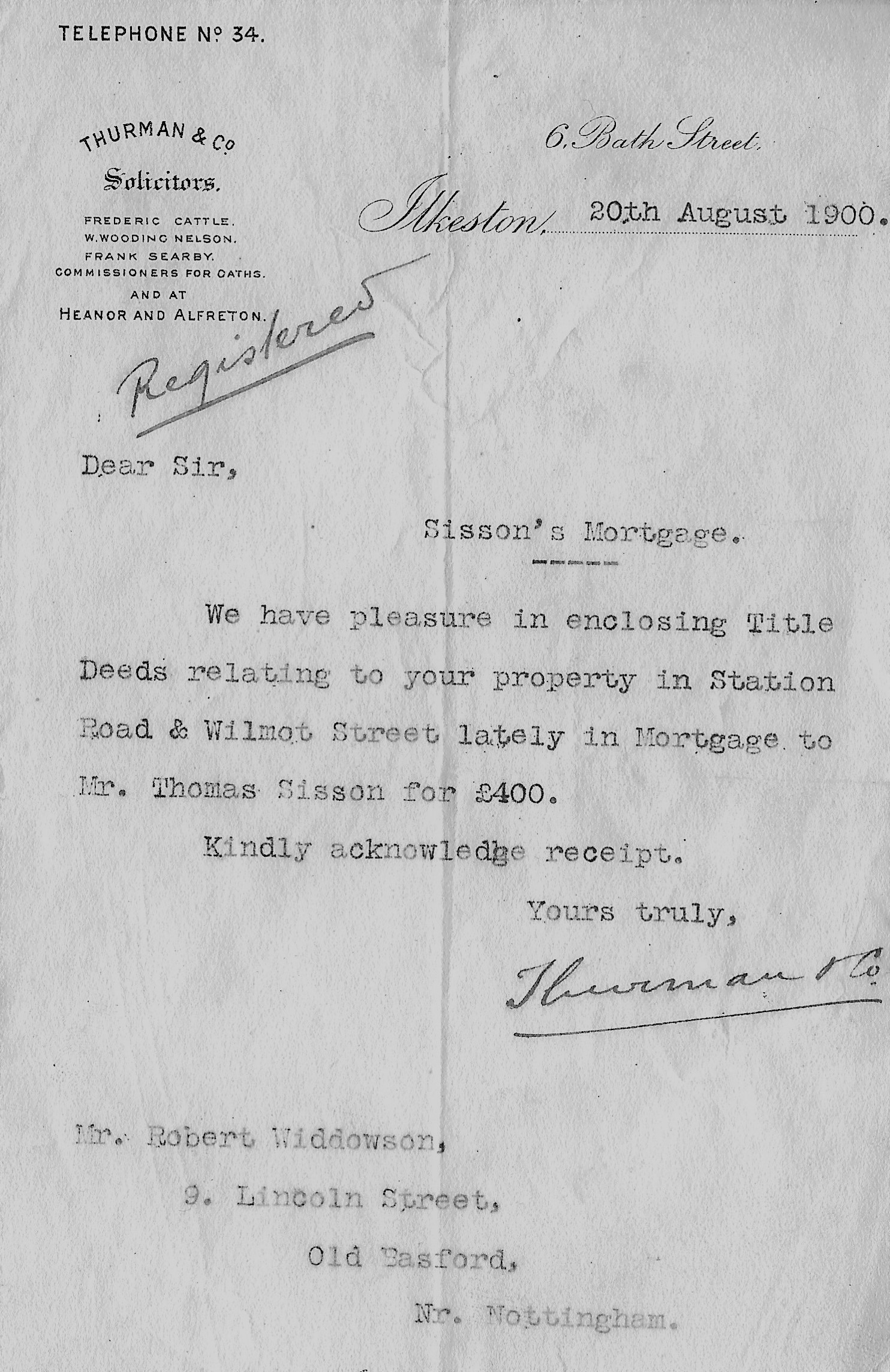

1899: Welcome to Robert Widdowson

On February 4th 1899 all his Station Road property and the cottage in Wilmot Street were conveyed by Walter Bonsall and his mortgagee Thomas Sisson, to Robert Widdowson, a grocer of 9 Lincoln Street in Old Basford. (Walter was now living at Highfield House in Marlpool). The price had now risen to £650. Of this, Thomas Samuel received back his loan of £400 and Walter got the remainder– £250. And of course Robert got the property.

Two days later Robert Widdowson mortgaged the Station Road and Wilmot Street properties to the same Thomas Samuel Sisson (!!) for £400. And just over a year later — on August 13th 1900 — Robert paid off the mortgage in full and thus the properties were reconveyed to him.

1900 .. Letter confirming Robert Widdowson’s ownership of the Station Road property

And Robert retained possession of the Station Road property for the next 30 years, at the end of which time he had left behind the grocery trade at 9 Lincoln Street in Old Basford and retired, (then working as a nurseryman), to Holbrook Lane in Belper.

On November 17th 1930 he sold the land, still of 376 square yards, together with the two houses, one still with a lockup shop to Arthur Cole, a tax collector living at 135 Hawton Crescent in Wollaton Park, Nottingham. The houses were at that time occupied by James Wright and F Thornton. The price was £350.

1930: Goodbye to 105 and 106 Station Road

——————————————————————————————–

And here is King Street, no longer a proposed new street 30 feet wide, but fully developed (Jim Beardsley archive)

————————————————————————————————————————

Frederick Henshaw, mentioned above, was born on June 15th 1853, the oldest son of John and Eliza (nee Straw). On April 17th 1876, he married Emily Aldred, daughter of James and Eliza (nee Thompson). They had two children, Henry (1881) and Eliza Ann (1884). Frederick and Emily both died at 24 Howard Street, Nottingham, in 1925 and 1935 respectively; they are buried together in Park Cemetery, Ilkeston.

1891: Home sweet home … at No 109 Station Road

Before we move on, we will linger for just a short time in this part of Station Road —just a couple of doors away, at number 109 Station Road. On the 1891 census this property housed the family of coalminer Edward Aldred, born July 6th, 1862; his wife Frances Ellen (nee Fox), born January 26th 1865; son George Arthur (April 22nd, 1886); Gertrude (January 25th 1888); and Margaret (May 24th, 1890). The two front rooms of this five-roomed property had just been let out to another family — lace worker Fred Lowe, his wife and newly-born son.

In early June, Fred discovered that his watch was missing, and through Bath Street pawnbroker John Parkin, discovered that Frances Ellen had most probably taken it. Fred confronted her, she denied the theft, but appeared mortified by the prospective shame of being accused of the theft.

A day later, two railway workers were busy on the Midand Railway line, near Ilkeston Park, the home of Mrs. Annie Potter, widow of John Cecil, when they heard cries coming from the direction of the Erewash Canal, 200 or 300 yards away, somewhere between Potter’s Lock and Station Road. This was about mid-afternoon. They ran past Park Farm, reached the canal, and saw Frances Ellen and baby Margaret in the water. Immediately, both managed to pull out the mother, and only then noticed the baby, floating on the opposite side of the canal. The child was retrieved when one of the workers jumped into the water but she was sadly and obviously dead. Frances Ellen was carried to a nearby cottage– the home of Pharoah Burrows in Sough Closes — where hot bottles to her feet, hot flannels to her body, and artificial respiration eventually led to signs of life. But this seemed to cause her great distress — “Let me go !!” she cried as she was then taken into the care of Alice Dean, matron of the Cottage Hospital in Station Road.

Later, a note was found at the canal bank, pinned to her hat and addressed to her husband though its contents were not immediately revealed. In the local press the ‘unhappy woman‘ was described as ‘widely known and highly esteemed‘, ‘most respectably connected, and has always borne an excellent character’. However a slightly different story was told by some witnesses at the subsequent inquest into the death of infant Margaret a few days later. Her neighbour, Eliza Williams of 50 King Street (her back door faced the Aldred house), testified to how distressed Frances Ellen was at being accused of theft, of how she was innocent of that crime but of how she could not face her husband. She told the same to her sister, Elizabeth Emma Long (nee Fox) who lived just round the corner, in Taylor Street. And then, when asked about the domestic circumstances of the Aldred family, her sister told of how Frances Ellen was most miserable — her husband Edward would not allow her enough to live on, and she had seen marks of abuse upon her, although she had never witnessed her being mistreated. And in his later testimony, Edward denied any physical mistreatment of his wife.

The inquest jury had no option other than to return a verdict of ‘wilful murder’ in this case; it wasn’t the duty of the inquiry to judge the state of her mind or to take that into account. This judgement however did not undermine the deep sympathy felt for Frances Ellen throughout her nighbourhood.

And once more, a few days later Frances Ellen was formally charged with murder, at which point she wrote a lengthy statement …

Frances Ellen was still too weak to attend any hearings, remaining at the Cottage Hospital. She was also several months pregnant with a fourth child. The local sympathy for her continued, such that a public fund was set up to receive donations for her defence.

That sympathy continued and was evident when Frances Ellen appeared for trial at Derby Assizes on July 20th. The prosecution counsel spoke of the mother’s clear love for her dead child, but if she took that child’s life as alleged, then she is guilty of wilful murder, no matter what misguided motive drove her to do it. Sympathy should not warp the judgement of the jury.

The trial then went through all the witness evidence, some of which confirmed the claims made against her husband by Frances Ellen in her letter, which was read out in court. Dr John Joseph Tobin was also called to describe her condition and state of mind — he described her as of a decidedly nervous disposition, with a temporarily ‘unhinged mind’, and with a tendency towards hysteria. Following this, several possible but unprovable scenarios of how and why Frances Ellen was motivated to enter the canal, were presented by the defence — probably designed to raise questions and doubt within the minds of the jurors, especially concering whether she wilfully and with malice aforethought did kill and murder her child. In his summary, the judge dwelt some time on discussing the behaviour of the husband, before returning to what might be considered by the jury in reaching its decision.

And then a decision was reached — after a quarter of an hour deliberation — not guity. And, amid applause, Frances Ellen walked free from court. She returned to Ilkeston by the 4.09 train, to be welcomed by a crown of several hundred, mostly women. On the same train, but far less ‘free’ was husband Edward Aldred; he received a completely different ‘welcome‘, being mobbed, struck with umbrellas, and pelted with stones and dirt, only to escape under police protection.

And now retribution !!! Edward got it ‘in the neck‘ from the local newspapers…. the human brute to whom Frances Ellen was married and who had subjugated her to domestic tortures and tyranny….. a ruffian who had impelled her to kill her child by his cruelties. An unmerciful beater of his wife .. he should be tied to a cart-tail and well-thrashed from the top to the bottom of Bath Street. It was hoped that the local populace would shun him, and eventually force him out of the town. He did lose his job and according to his mother, just rambled around the fields for a while.

Shortly after, it was rumoured that Edward had gone ‘over the sea‘ just as his wife was charging him with assault and seeking a judicial separation. In his absence he was sentenced to six months in jail with hard labour — the maximum allowed by the law for this offence — and ordered to pay 10s per week to his wife, who was given custody of the two children. The separation was allowed !! As the Derby Daily Telegraph pointed out, “Of course, she will have to whistle for this allowance, but the woman will be freed from a hateful presence, and, aided by the sympathy of her friends and neighbours, may yet be able to live in peace and comfort”. To facilitate this, a public subscription was organised by the Rev Edward Muirhead Evans, Edward Miller Mundy of Shipley Hall, and the Mayor of Ilkeston, William Tatham. With such ‘lofty’ sponsors it couldn’t fail, and within a few weeks over £500 had been ‘invested’ for the family’s future.

At the end of the year, Frances Ellen gave birth to her son, Sydney Edward Aldred who was baptised with his sister, Gertrude, on June 5th, 1892, at St Mary’s Church. Sadly, he died on June 22nd, aged 7 months.

In 1894 Frances Ellen was living in John Street, off Station Road, using her fund and any income she could earn from taking in lodgers. With her were John Booth, a postman, and his younger brother William. There were rumours of ‘impropriety’ which Frances Ellen emphatically denied, but as the end of the year approached it was clear, at least to some, that she was pregnant once more. On December 10th Elizabeth Moon, a neighbour and Jane Bennett, a ‘midwife’, were called to her property where they found that she had given birth to a daughter who had almost immediately died. When Dr. John Joseph Tobin subsequently carried out a post-mortem, he concluded that death was caused by suffocation, though there were no marks of violence on the body. The child was fully developed and had had a separate existence. Frances Ellen had not tried to conceal the birth however as she had engaged a midwife during her confinement, showing that she had every intention that the child should be born alive. At the inquest into the death, held at the Durham Ox, the Coroner was suspicious, largely because of the previous history of the mother; there was a lack of any evidence however to be definitive about how the suffocation had occurred. This didn’t stop the jury recommending that Frances Ellen should be severely censured — she should have sent for help earlier in the day !!

On December 27th, Frances Ellen and John Booth stood together in the dock, at Ilkeston Petty Sessions, she accused of murdering her infant daughter and he of aiding an abetting her. At the hearing the two women who had attended Frances Ellen testified that the child had been born before they arrived and they found her dead. Dr. Tobin confirmed that the child had lived perhaps for about 30 minutes, though he could not be sure of that time, and had died of suffocation. After a further hearing, the two accused were committed for trial at the Derbyshire Assizes, just over two calendar months later. By that time, rumours had been circulating in Ilkeston — that John was the dead infant’s father, that Frances was living ‘immorally’ with him, and that he had admitted to a midwife that neither he nor Frances Ellen wished to let the baby live. The Assizes lead magistrate submitted that they were not present to pass judgement on the couple’s morality and it was clear that neither had tried to hide the pregnancy nor the birth. The Grand Jury very quickly established that there was no case to answer and both were immediately discharged.

On the 1901 census Frances Ellen is recorded as the ‘wife‘of postman John Booth, about 20 years older than her, living now at 139 Nottingham Road. With them, are her children George Arthur and Gertrude, and now a daughter, Mabel Fox Booth, born in 1899. The family can also be found on the 1911 census, where daughter Winifred Booth, aged 8, also appears.

I have yet to find a marriage for John and Frances Ellen.

————————————————————————————————————————

Let’s now wander over to the north side of Station Road and see the development taking place there in the late Victorian period