I wonder how many times Adeline Wells paid a friendly visit to socialise with “the rest of the tenants (of Wakefield’s Yard) who were mostly Irish, and rather noisy, so also were the tenants of Evan’s Row.”

———————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Irish immigration to England dates back further than most people realise. Rather than as a phenomenon of the mid- to late- 19th century, the Irish had been migrating across the sea for centuries, usually in search of seasonal work or longer term opportunity. Some towns – especially London, Bristol, Whitehaven – had a population of middle class Irish traders as early as the 1650s (https://www.irish-genealogy-toolkit.com/Irish-immigration-to-England.html)

The Great Famine in Ireland in the second half of the 1840’s led many Irish families to seek a better life in neighbouring England. And quite a few came to Ilkeston.

An Irish Famine illustration from The life and Times of Queen Victoria by Robert Wilson (1900).

An Irish Famine illustration from The life and Times of Queen Victoria by Robert Wilson (1900).

One of these immigrants was Michael McMane who was living temorarily in Ilkeston in 1848. One Sunday in April he was on his way to Mass, having changed into his new trousers, when he remembered that he had left his purse containing three and a half sovereigns in his old trouser pocket. The money had come to Michael from his home in Ireland to help fund his emigration to America. When he got back to his lodgings he discovered that a fellow tenant, Patrick Fury, had removed the purse “for safe keeping”, and then had decamped with it. Michael’s trip to America was “put on hold”.

The 1851 Census records 59 Irish persons in the town, 34 of them working in the iron/metal trade (58%). By 1861 there were 151 Irish members of the Ilkeston community, 47 of them working in the iron trade (31%). Obviously, living in this part of the town, with its proximity to the ironworks at Stanton, would be very convenient.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————-

A very brief outline of the Stanton iron works

In 1846 Benjamin Smith of Chesterfield and his son, Josiah, established three blast-furnaces in the parishes of Dale and Stanton-by-Dale, by the Nutbrook Canal. Each furnace made 18 to 20 tons of pig iron per day. There was a small general foundry and local deposits of ironstone, while coal and limestone were transported to the works by the canal, and pig iron was sent to customers via the same route.

Three years later the firm took the name The Stanton Iron Company but in 1855 it was taken over and changed its name to The Stanton Iron Works Company. That was when George and John Crompton came to Stanton. George Crompton was born on October 13th 1823 and was educated at Rugby while Dr. Thomas Arnold was headmaster there, and then at Trinity College, Cambridge.

Between 1865 and 1867, Benjamin Smith’s original three furnaces were replaced with five new furnaces. This site becoming known as the Old Works. However the company soon experienced financial difficulties and there followed a series of take-overs, the business eventually being taken over by the Crompton brothers. Their family was to own the company for over 80 years.

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 created a huge demand for iron and the works grew rapidly with the construction of new furnaces and foundries (the New Works) alongside the Erewash Canal in the early 1870s. Ironstone properties were acquired in Northamptonshire, collieries were sunk in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. About 1875 house building for the workers was started — these workers often coming from Staffordshire, Shropshire and the Black Country.

In 1877/78 the Crompton partnership became a limited company and the title underwent another change to The Stanton Ironworks Company Ltd. George was then chairman of the company and held that position until his death, at his home of Stanton Hall on November 14th, 1897. By that time the ironworks had eight furnaces, each one double the capacity of the original ones. There were extensive works at Stanton by Dale and Hallam Fields, collieries at Teversal, Pleasley and Silver Hill, and ironstone mines in Leicestershire, Lincolnshire and Northamptonshire …. while workers (estimated to be about 5000) were provided with housing, institutes, churches and schools.

And in October 1898, at the Derby County Hall, the magistrates confirmed the granting of a licence to the new premises proposed to be erected at Hallam Fields by the Stanton Ironworks, to be known as the Railway Hotel. The licence had previously been granted by the Ilkeston Bench on September 1st and was now confirmed.

No sooner had it opened for business than ‘the Railway‘ ran into trouble. In January 1899 the manager of the hotel, Thomas Mee, was up before the magistrates charged with selling whisky and gin more than 25º under proof !! His defence was that it was entirely accidental, caused by a faulty hydrometer. In addition he was only the manager, employed on a weekly wage, and so did not order or pay for the spirits. The hotel was owned by the Stanton Company who bought in the stock and owned the defective hydrometer … so the fault lay with them. The Company admitted the error, expressed its regret, and paid the fine of 6d plus costs.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————-

The 1850s

Living in Wakefield’s Yard the Irish tenants, noisy or otherwise, included families Donald, Donohoe, Holloren, Kelly, Manion, McDonough, Moran, Quin and Regan.

1853. Jerry is the man!

In the early hours of a frosty, star-light, Sunday morning in January 1853, 25-year-old framework knitter William Bowskill, alias ‘Jerry’, was standing opposite the White Lion Inn, talking to Charlotte Hofton alias Stirland (nee Hooley) whom he had met walking from Baptist Chapel Yard in South Street.

The reason why Charlotte was strolling around the town at this early hour might be found back in East Street.

The pair chatted and were presently joined by framework knitter James Tunnicliffe. Suddenly two men came from the toll-bar direction and ran past them. Almost at once appeared a group of about a dozen Irishmen chasing the two men. But they didn’t run past but stopped at the chatting trio. There were cries of “here is Jerry! Jerry is the man! That’s him !” whereupon the latter was subjected to a vicious and unprovoked attack, beaten over the head with a coal hammer, a poker and wooden sticks.

Charlotte rescued ‘Jerry’ and took him, bleeding and dazed, to his nearby lodgings where his wounds were treated.

Later that day he complained of feeling unwell — not unsurprisingly as he was suffering from severe head injuries and a fractured skull — and within two days he was dead.

One witness to the attack was labourer Samuel Doar and like Charlotte, he ‘fingered’ Irishman John Divney, a miner at Stanton ironworks, as the wielder of the hammer. Further statements implicated other Irishmen.

After the attack but before Jerry’s death, parish constable George Small went to question John Divney and recovered a coal hammer from his ‘Quin’ lodgings at Wakefield’s Yard. John desperately tried to construct an alibi using the testimony of neighbour Mary Ann Taylor alias Hawley but the jury at the subsequent inquest was unconvinced and John was committed to trial at Derby Summer Assizes on the charge of Manslaughter.

At his trial another jury found him guilty. The Chief Justice remarked that he was extremely lucky not to have faced a charge of Murder in which case he would now be awaiting his execution. On this lesser charge John Divney was sentenced to transportation for life and he departed Portland prison in April 1855, on board the ‘Adelaide’* for Fremantle, Western Australia. He arrived three months later.

*Bound for the Swan River convict colony, W.A., the ‘Adelaide’ left Portland on April 10th 1855 and reached Freemantle on July 18th of the same year. It carried 93 passengers and 260 convicts (one of whom died on route).

John Divney aka Devney was listed as Convict No. 3527, aged 32, sentenced to life for murder at Derby Assizes on March 8th 1853.

He was described as 5 feet 5 inches tall, middling stout build, with dark brown hair, grey eyes, dark complexion and a long pockmarked face. (Convicts to Australia … Convictcentral.com)

On board the same ship was Thomas Copestake of Codnor Park, sentenced four months after John, at the same place, to 15 years for stabbing with intent. (see The Ilkeston Permanent Building Society).

1856 A brutal assault.

In 1856 the Pioneer reported an ‘English and Irish Row’ ….

“Michael Howard, Dennis Wood, Peter Conolley, Peter Coruton, Patrick Fitzpatrick, and James Kay, Irishmen, were charged with brutally assaulting Henry Harrison and Frances Syson on Saturday last, at Ilkeston.

Harrison and Syson were in Court, and their damaged frontispieces gave evident proof of the conflict they had had with the souls of Erin, some of whom had also been well mauled in return by the English.

The Magistrates considered that there was ample proof to implicate all six of the defendants, and adjudged them to pay 16s each, or be committed to jail for six weeks”.

1857. ‘I’ll have the law’ .. or perhaps not!!

Not always were the Irish of Ilkeston the sinners but were sometimes sinned against — or so they testified.

In an assault case of the following year Irishman Michael Connolly appeared in court at Derby Sessions to accuse Edwin Wright of maliciously wounding him with a knife — and Michael had brought his mates to back up and prove his claim.

Perhaps because of their accents, the way they gave evidence or what they said, they don’t seem to have been treated with much seriousness or respect by many in the courtroom.

Thus…William Manion, when asked what he was:

“An Irishman, and I’m not ashamed to own it”. (laughter in court)

“I live up a yard, at Divney’s lodging-house. I was sitting up the statutes night, at two o’clock in the morning, waiting for my brother who had come to the statutes. About twelve o’clock I heard a noise and went to the door, and saw the prisoner”. (more laughter)

“I’m not come here to be made ‘gam’ of and I’ll not be made ‘gam’ of. I came here to spake the truth, and although I am an Irishman I’ll have the law”.

William went on to describe how Edwin Wright, an acting Parish Constable, had come to the lodging-house in search of a suspect and had ended up assaulting William and his brother and then stabbing neighbouring lodger Michael Connelly.

He continued;

“There was nobody in the house but me and my brother Peter, for the others were in bed”. (laughter)

When asked how many were in the house, William hesitated: “I’ll tell you if you give me time to count them. (pause) I do not know if any of them were gone out, but if they were not, there were six men”. (renewed laughter)

“Me and my brother were sitting in what we call the kitchen in England but in Ireland we called it a ‘poltroon’”.

When Peter Manion was later asked if he was William’s brother, he replied ‘My mother says I am’. (much laughter)

When it came to the turn of the defence, several witnesses stepped forward to give Edwin Wright an excellent character reference, including constable George Small and Inspector Fearn of the Derby Police.

After a short consultation the jury acquitted the accused.

And again in 1857 … another intra-Irish disagreement.

Jan 17th at Smalley Petty Sessions, Michael Hays charged James, Thomas and Andrew Calla with assaulting him at Ilkeston on January 3rd — case dismissed.

James Calla charged Michael and John Hays with assaulting him at the same time and place — case dismissed.

James Calla charged James and John Hays, and Robert Walking with malicious damage to his front door on January 4th at Ilkeston — case dismissed.

The magistrates showed great patience and attention when investigating these cases, but recommended that the parties should now go home and be better friends in the future.

The 1860s

Michael O’Day and son.

Michael O’Day, his wife Mary (nee Hurley) and their children had left Ireland in the 1850’s and arrived at Evan’s Row where Michael worked as an ironstone miner. He also kept a lodging house to accommodate several of his Irish compatriots.

At times his younger son, Michael junior, officiated as a clerk at the nearby Roman Catholic chapel and ‘was highly respected among the Irish’.

In the 1860’s the family moved north where Michael junior found work at the Denaby Main Colliery in South Yorkshire.

On one of his rest days he was visiting Conisbrough Castle and chose to climb a tree to take a rook’s nest, but fell, broke a foot and ankle and had to have his leg amputated.

Sadly he died shortly after, of internal injuries, at the age of 19. He was buried at Doncaster.

Father O’Neill, Irish priest.

“In fact the Catholic priest was often called on to quell these noisy (Irish) people”.

In the mid-1860’s — when the Fenians were agitating for Irish independence — disruption often spread to Irish communities in England. At that time in Ilkeston, members of the police force were given permission to wear cutlasses for protection from any potential raging Irish Republicans.

One Christmas Eve, Inspector Brady led his men, complete with said cutlasses, to quell a serious disturbance, around the ‘Irish Quarter’ of Evan’s Row and White Lion Square. However the troublesome Irish did not readily respond to the Inspector’s order to ‘disperse; be goan’ home’ — he too was Irish.

It was only the appearance of another Irishman — Father Hugh O’Neill of the Roman Catholic Church — armed with his walking stick, which persuaded his flock to disperse.

Father O’Neill is perhaps the Catholic priest to whom Adeline refers (above) though she might have recalled Father Arthur McKenna, both of whom we have recently met.

1867. And a Merry Christmas to you all!!

Christmas Day of 1867 and peace and goodwill were far from the minds of some residents of this locality, chiefly inhabited by the ‘down-trodden inhabitants of sweet Emerald Isle‘. (IP)

At one o’clock in the morning a group of revellers — including a Corporal of the Grenadier Guards and a young man called Booth — was a short distance down Nottingham Road when a brick-end whizzed past the nose of the Corporal and struck poor Booth in the mouth, knocking him to the ground where he lay partially stunned. The Irish were immediately identified as the culprits of this cowardly ambush which could not pass without retribution.

The Corporal’s troops hastily armed themselves with hedge stakes and palings to make a vigorous frontal assault on the enemy position. Reinforcements were quickly called up by both sides and furious conflict raged for some time, ’the Irish men and women yelling like demons and brandishing their pokers and knives in all directions’. They were greatly outnumbered however and soon considered the best battle plan was a tactical and very swift retreat into their homes which were saved from severe damage by the arrival of the police.

The Corporal’s storming party was banished from the scene and made off towards the Market Place, but tempers were still raging and blood was up.

Possibly along South Street, a detour allowed the group to attack ‘Paddy’s residence by storm’, pelting doors and windows with stones carried there specifically for the purpose. A second intervention by the police calmed the fracas once more and the troops demobilised.

The Pioneer reflected on the Christmas morning scene…. several torn down palings, smashed windows and doors, large granite stones scattered in all directions.

The 1870s and 1880s

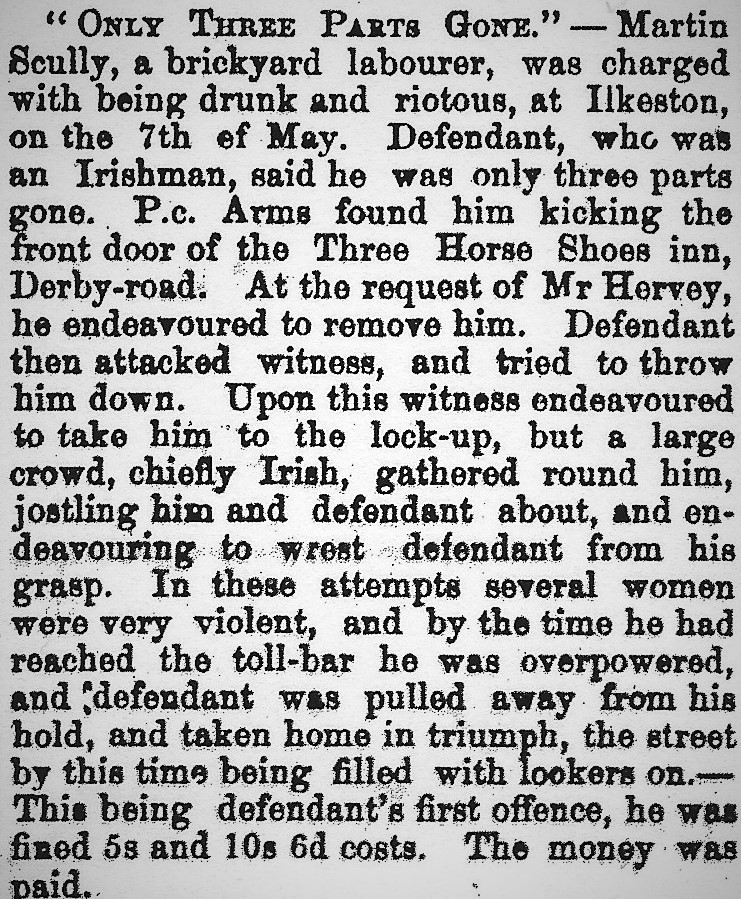

1874. Only three parts gone

from the Ilkeston Telegraph May 30th 1874.

Not the only occasion when Ilkeston’s Irish community demonstrated its solidarity.

Can I see my mate please sir ?

from the Ilkeston Telegraph June 13th 1874

Had Mick gone to see Martin ??!

1880. Kellys’ lodging house

For over 20 years Irish-born couple Margaret and Matthew Kelly kept a lodging house at Wakefield’s Yard which in 1880 was described as ‘not fit for any person to enter, and certainly not fit for human habitation’.

It was suggested that it ought to be pulled down to its very foundations.

These remarks came from the Coroner at the inquest into Matthew’s death. Margaret had died only a week before and this had left her sickly husband in a melancholy state. An ‘Irish Wakes’ was organised for Margaret at which Matthew, his son Austin, the latter’s wife Elizabeth (nee Devers) and several ‘neighbours’ consumed a significant quantity of liquor such that Sergeant William Colton had to be called to quell the disturbance. Matthew confessed to the sergeant and several others that Margaret’s death had left him tired of life and he would rather now be dead — a wish he achieved within days, after he cut his throat with a razor.

Despite the Coroner’s recommendation, the Kelly building wasn’t pulled down.

Soon after the deaths of his parents Austin applied to the Local Board for permission to run a public lodging house at the same address. The Board withheld its permission until such time as the drainage within the Yard was improved and almost immediately the Board began work on the sewers in this area.

Thomas Lally, labourer of Extension Street, was acting as night-watchman while the excavations were in progress when about midnight on Saturday Benjamin Hardy of Kensington wandered by. Thomas cautioned the stroller to be careful and Benjamin sauntered off in the direction of Stanton Road. Two hours later a semi-drunk Benjamin was back, spoke a little and staggered off once more. He was not seen alive again.

About half past seven on the following Sunday morning Owen Bloor of Regent Street, a clerk at West Hallam Ironworks, was walking down Pimlico and found Benjamin lying dead, embedded in a sewage ditch at the side of the lane — his body covered, neck to feet, in mud. There were signs that he had struggled violently but unsuccessfully to get out of the ditch.

Dr. Wood’s subsequent examination of the body revealed some blood marks and bruises on the nose and both knees. There were no signs of foul play. He concluded that Benjamin had died from suffocation and exposure to the bitterly cold weather.

Benjamin was about 66 years old and had recently left the Basford Union Workhouse to return to Ilkeston.

Austin Kelly had married Elizabeth Devers in 1866 at St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in Derby when his name was recorded as ‘Augustine’.

1881. An Irish mob.

The Irish were out in force in May 1881 when an estimated crowd of about 200 people, 150 of them Irish, turned out to watch Michael Grady trying to rescue his son John from the clutches of the police in the form of P.C. John Downing.

Irish John was drunk and had not only assaulted the policeman but his helmet and lamp as well, when his father intervened to attempt his premature release from custody.

Both father and son subsequently appeared at Ripley Petty Sessions where John was given several fines and a month’s term in jail while his dad’s 13 previous convictions counted against him and led to a two-month jail sentence.

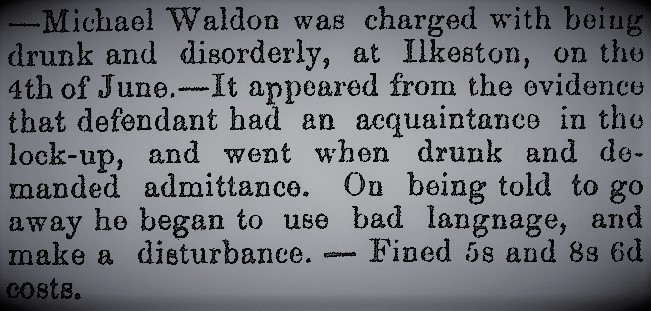

1885 Walter Lally, shoe seller

One Irish immigrant who successfully established a business in Ilkeston was Walter Lally who, by 1871, had arrived in the town with his parents and siblings … to settle initially at 8 Extension Street.

By 1881 Walter’s trading premises were on the west side of Bath Street, close to its conjunction with Mount Street, where he acted as manager for Thomas Brown, boot and shoe maker. By 1885 however, he had moved into his own premises in South Street, opposite pawnbroker John Moss — which was very fortunate for collier William Pickering. The latter came into Walter’s shop on New Year’s Day of 1885 and handed him a note from his ‘employer‘, Charles Baker, an underviewer at Oakwell Colliery, which stated that the bearer was entitled to a pair of boots to be paid for by the Colliery owner on the following Saturday. Walter duly obliged and another satisfied customer left his store … so satisfied that the collier immediately went over to the shop of John Moss and ‘pledged’ his new boots !!

It was later, of course, when Walter realised he had been duped and consequently charged William with obtaining goods by false pretences. By that time, realising that his ploy had worked so well, the next day the collier had ‘obtained’ a ham from the Bath Street store of provision dealer Enoch Carrier. And when he was charged, it was discovered that on New Year’s Eve, he had also acquired three picks and one tool handle from ironmonger John Andrews, again in Bath Street.

Now collier William had run out of luck and he was committed for trial at the next Quarter Sessions. He didn’t have long to wait … less than a week later he appeared at the Assizes and pleaded guilty to all three offences. He was sentenced to 18 calendar months imprisonment, with hard labour.

At this time Walter was living with his first wife Bridget (nee Mooney) and their two children. Bridget died in 1896, aged 43 and in 1898 Walter remarried, to Mary Mitchell (nee Cockayne). The bride had also recently been widowed when her husband, Abraham Mitchell Campbell died on July 31st, 1897 — he was a lacemaker though he came from a family of shoemakers/cordwainers. It would seem that stealing boots and later pawning them was a lucrative trade which some would choose rather than working for a wage, and Walter was to fall prey once more. He was still at his premises of 23 Bath Street in February 1899 when they were ‘visited’ by Catherine Smith of Daykin’s Yard, further down Bath Street. His son 19-year-old Walter Francis was serving in the shop and had hung a pair of boots on display outside the shop. When he came to bring them back inside, as the shop was closing at 6pm, he noticed that they had gone. The police were informed and although the boots had no distinguishing ‘private’ mark no one else in the town sold the same footwear; the Lallys had an agreement with the makers not to supply any other sellers in Ilkeston. The obvious place to start the search for them was at the local pawnbrokers and sure enough, a visit to John Eaton & Son at 18 Granby Street quickly located them and the person who had brought them in. Catherine was arrested and at the Petty Sessions was fined 10s with £1 8s costs, or 10 days in prison.

Walter Francis Lally continued the shoe and boot retailing tradition and returned to 23 Bath Street … there he died a bachelor on September 22th, 1956, aged 76

Above, the Lallys outside 23 Bath Street, with Mount Street on the right.

Right, waiting to be ‘converted’

John Francis Lally (1914-1994) was the son of plumber John Thomas Lally and thus Walter’s grandson … who developed not into a plumber or shoe salesman, but a respected and much-loved schoolmaster, and a fine artist too.

The Museum and Grand Hotel, Scarborough by John Lally, from the Erewash Museum Collection

1887 Jubilee Celebrations

Aged 33, Thomas Quinn, like all his siblings, was born in Ilkeston though had Irish parents. He also had a ‘criminal record‘ as long as your proverbial arm. In the previous 20 years he had over 20 convictions, the majority for being drunk and riotous, with a couple of assaults on the police, and a smattering of theft and wilful damage thrown in.

In June 1887 Thomas was determined to join in the town’s Jubilee celebrations for Queen Victoria. Already well on the way to total inebriation, he visited the South Street grocery and beer-off store of Richard Evans Brealey and demanded his “Jubilee pint of ale“. Richard’s refusal to serve him led Thomas to issue Richard with a warning : “look out for dynamite” before he then smashed the shop window and several jars of jam displayed there. Found guilty of ‘misdemeanour‘ Thomas was sentenced at the Quarter Sessions to three months in prison, with hard labour.

In April of the following year Thomas was back at the Petty Sessions, facing his 27th conviction, charged with vagrancy. However the magistrates decided to give him another chance and discharged him. Thomas left the court and immediately promised ‘to sign the pledge‘ for a year. That pledge lasted precisely one month … and then, on May 7th 1888, Thomas was back in court with his mate, George ‘Toby’ Wright, accused of once more breaking the shop windows of Richard Evans Brealey. The reason was as before — Richard had refused to supply the pair with drink. Thomas’s defence was that he was so drunk, he didn’t know what he was doing !!

At the Quarter Sessions in July of that year, Thomas was sentenced for this window-breaking — 12 months in prison with hard labour. His mate George was given six months and hard labour (presumably because he had fewer previous offences). In passing, it might be noted that, by 1890, grocer Brealey was insolvent … was it because of the expense of too many broken windows to replace ?!! — Richard blamed it on bad trade, poor health and his large family of a wife and eight children.

And who’s this, charged with drunkenness and using bad language in Park Road at a quarter to midnight, on May 25th 1889 ? Why, none other than Tommy Quinn !! Another fine — or 14 days inside. And in September Thomas was back at the Petty Sessions, pleading victimisation ! He had only been out of prison for a couple of months and the police had arrested him once more for drunk and riotous behaviour; they were always after him as soon as ‘he had a drop of booze’. Another fine and costs, or 14 days inside.

It appears that Thomas Quinn and George ‘Toby’ Wright were drinking ‘buddies’. They were out together again on November 18th 1889 and ended the night drunk and disorderly. At the subsequent Police Court, Thomas accumulated another fine but George had taken his drunkenness a step further and had ended up assaulting P.C. Andrew, for which he was given a one-month jail sentence with hard labour

The 1890s

1890 An Irishman on the School Board

On the evening of June 18th, Mary Ann Grady (nee Helbert) — the only one of her Oxford Street family born in Ireland — was in a large crowd of people assembled in the Market Place, awaiting the announcement of the election results for the new School Board. Several of those elected came out of the Hall to address the crowd, including the Roman Catholic candidate Father James McCarthy, When James started to speak, from the crowd Thomas Meakin junior shouted a threat, that he would pull the Father off the stage. Mary Ann intervened, to declare that the Rev Father had as much right as anyone to be there, and when Thomas jun. threatened her too, she cracked him over his head with her umbrella, splitting his head open.

At the Petty Sessions, Mary Ann was fined 2s 6d plus 14s 6d costs, or seven days in prison. She chose the latter.

And after serving her time, Mary Ann was back at the Sessions, in September. Her husband was accused of assaulting Mary Ann Connell, while the latter was accused of assaulting John’s wife, Mary Ann Grady, while the latter was accused of assaulting Mary Ann Connell. Much biting and gouging and hair-pulling were included, along with discreditable language and an assault with a pickled cabbage !! The magistrates described the arguments as fuelled by drink, while the residents were “a disgrace to the neighbourhood”. All charges were dismissed and each had to pay their own costs.

And then, at the same Sessions, there was, of course, Michael Waldron, of Truman’s Court but originally from County Mayo, only 40 years old, who was about to record his 31st conviction for drink and rioting offences. And by September 1891 Michael had managed to increase that number to 34, for which offence he was granted a stay of 14 days in prison.

1892: the pattern continues

Several members of the Durkin family (travelling Irish workers en route to Lancashire), already the worse for drink, entered the White Lion Inn; the waiter, Arthur Vose, refused to serve them, whereupon they kicked two plates of glass out of the Inn door, and then gave Arthur a beating, for good measure. In response to the disturbance, P.C Robinson was sent for and was soon on the scene; however he immediately received the same treatment as the glass door. “The constable gallantly maintained a struggle against desperate odds, against opponents fighting and kicking with the desperation of madmen”. Reinforcements then arrived and, kicking and screaming, the drunkards were carted to the cells of the Town Hall lock-up (as custom, followed by a substantial crowd of their supporters), there to be greeted by Inspector Daybell. The latter was writing down the particulars of the fracas, his back turned towards the ‘alleged’ culprits, when one of them seized his clog and with it, attempted to brain the Inspector. Fortunately the attending constables were alert to the danger and were on the assailant before he could carry out his intention.

The landlord, William Pounder, had tried to assist the police during the disturbance, but being affected with a weak heart, he quickly fell down and had to be carried to bed.

At the subsequent Petty Sessions, all the accused received prison sentences for the assaults, fines for the damages, though the drunk and disorderly charges were suspended for six months. AND who should appear at the same Petty Sessions ?? … you guessed it !! None other than Michael Waldron, now making his 36th appearance. He received one month inside for being drunk, and an extra seven days when he refused to pay the fine for costs and damages (to the door of a cell at the lock-up).

1893: Drinking buddies still

Tommy Quinn and George ‘Toby’ Wright were still out on the town together, still getting drunk together, and still appearing at Ilkeston Petty Sessions together, this time on August 19th, charged with …. need I continue ??!! And this time P.C. Gotheridge was kicked in the face and his watch broken. Sergeant Riley went to his rescue and Tommy ended up being taken to the police station on a stretcher. He later collected a sentence of over five weeks while George got a fortnight in jail.

May 1894: Tommy on his own this time

Another charge of drunkenness for the Irishman who didn’t even bother to turn up to the court. The charge was not only ‘being drunk and disorderly’ but ‘being drunk and refusing to quit licensed premises’, namely the Three Horse Shoes where John Harvey junior was landlord. The latter tried to eject Tommy who turned violent, threatening to break every window in the pub .. only failing to carry out his threat when John forcefully intervened. Tommy got another fine and another 14 days in jail.

Three months later and it was conviction number 46 … and a sentence of 14 days in jail for being drunk and disorderly. And in October number 47 followed. This was his fifth conviction for 1894 which ‘beat’ his average of four per year. But he didn’t get a gold medal, he got another 14 days in jail.

September 1894: A brutal son

And keeping up with Tommy Quinn was Michael Waldron. At the end of September 1894 he was at the Petty Sessions, charged with being drunk and disorderly, and now with over 40 convictions behind him. His mother also appeared there, with a black eye, explaining that she got it from her son while trying to get him out of bed … he just wouldn’t go to work !! Another conviction followed, with 21 days in jail and without the option of a fine.

Tommy and Michael were almost next-door neighbours at Trueman’s Court. Were they involved in an unspoken contest ?? If so, Michael was quietly catching up with Tommy … on November 20th, 1894 the former committed his 42nd ‘drunk and disorderly’ offence and spent another month in jail. He had been attending these Petty Sessions for just 20 years now. However Tommy made his half-century and then moved on to number 52 in mid-June 1895.

August 9th and 14th 1895: George ‘Toby’ Wright branches out on his own

George, as usual drunk and disorderly on August 9th at Ilkeston, added a new offence to his repertoire — begging under false pretences, on August 14th at Heanor. As most people in Ilkeston would know him, he had travelled to the neighbouring town to try his luck, carrying a card on which was printed “Awsworth Colliery, near Ilkeston — The masters have stopped the pits because they have no sale for the coal till trade improves. If you please could you give me a small assistance, which will be thankfully received”. He may have fooled some people there but he didn’t fool P.C. Cosgrove, who quickly took him into custody. George had never worked at the colliery but had simply bought the card at Derby for 6d, and was showing it around. This was his 34th conviction and he was given a total of three weeks in jail.

June 13th 1896: Tommy and his tin whistle … and later in November … and into the next year … and the next !!

Tommy Quinn made his 58th appearance in court, for being drunk and disorderly on June 13th in Nottingham Road. He had by now refined his ‘not guilty’ testimony. Tommy was claiming that his wobbling gait was because he was blind in one eye while the other was going .. so people thought he was drunk when he was really sober. In fact he argued that he could walk straighter when drunk than when he was sober. In the winter months he got his living by getting coal in, but at this time of year there was not a lot of coal to get in. So now he had to get his living by playing on his tin whistle along the road. He begged the magistrates to give him his ‘discharge’ now, and promised that he would leave the town for ever.

Once more he was awarded a month in jail, but it was deferred as long as he was of good behaviour. At first Tommy couldn’t understand the punishment and had to have it explained to him; then he thanked the judge and promised never to play his whistle in Ilkeston again.

And five months later, on November 26th, Tommy was trying the same defence at the same court for the same offence — his poor eyesight made him appear to be drunk. It didn’t work then and it didn’t work now. Between a fine and 14 days in jail, Tommy chose the latter.

Tommy was still playing his tin whistle around Ilkeston’s streets in August 1897 … and of course was still drunk and disorderly whilst doing so, at least according to PC Sissons who arrested him at the Tollgate area. In his own defence Tommy insisted that he had only thrown his cap on the ground, in “Lancashire style” so that people might spontaneously give reward for his playing, which he argued was as good as any Germans and Italians. He was just a poor lad, going blind, and wasn’t really drunk at the time … he had just been mingling with the aristocrats, getting their coal in, and had been offered a lot of beer in payment. His argument was that he had been in prison so often that he was so weak when he came out that he could stand no beer. This didn’t wash with the magistrates who once more fined Tommy, or else seven days in jail. The ‘musician’ asked for, and was granted, time to pay his fine.

In May 1898 Tommy was at the Petty Sessions for the 66th time, facing the same charge — “the police have got it in for me” — with the same promise to leave the town if he were freed. Which he was free to do, but only after he had served his 14 days in prison !!

By August 1898 Tommy had notched up 67 convictions and was in court for number 68 …. this time it was a rather more serious offence. As usual he was drunk and disorderly, this time outside the Rutland Hotel, and was insisting that he treat the patrons there to a few tunes on his tin whistles. When he was informed that they would rather forgo this pleasure, Tommy was most upset and ended up assaulting P.C. Wallis. and Fred Jolly, a waiter at the hotel. For the offence of drunkenness Tommy was awarded a month in jail, and for assault was given an extra two months, the sentences to be served consecutively.

At the end of May 1900, Tommy had taken to sleeping out-of-doors; he had been found in some outbuildings at the bottom of Queen Street, lying in straw. What alarmed the police constable who found him however, was that Tommy had a pipe and matches in his possession !! The Irishman argued that it was the Queen’s birthday (May 24th) and so he should be granted a ‘special discharge‘. He promised to leave Ilkeston immediately and not return before next Christmas. The magistrates had heard his promises many times before — this was his 74th appearance — and he was sent to Derby for seven days.

Another conviction for Tommy came up shortly after, in August 1900, when he was at the Travellers’ Rest once more, this time fighting with his brother John. At this time Tommy declared that he was blind in one eye, had heart disease and a bad leg, so that he would be unable to work if sent to prison. If the magistrates could only find it in their hearts to bind him over, then he would try and reform. In his defence he stated that he had never been convicted for felony, until Inspector Lakin reminded him of a two months’ sentence for theft !! This time he got 12s costs to pay, or 14 days inside.

Tommy made his 82nd appearance — this one for drunk and disorderly — on December 27th, 1900. He stood at the Petty Sessions and outined his defence.

Tommy: I was going up South Street to play my whistle and they (the police) made after me. Then of course I got a little bit agitated, and I suppose they thought I was drunk. If they had followed someone else instead of me there would have been a bit of sense about it. I mean somebody that would have paid a bit of money when brought up.

It is now four months since I came out of prison, and my trade, that of coal getting-in, is a bit more lively now. This is the first Christmas I have had out of prison in five years, and on this occasion in celebrating the event, perhaps I had a drop too much. I have enjoyed myself, as I hope you have done. I wish you a ‘Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year’. I tried to enjoy myself. I’m sure, and I hope you will consider my case and be easy with me.

Magistrate: What is the date of the last conviction ?

Inspector Lakin: He has been convicted five times previously this year, the last date being on the 2nd of August.

Tommy: I remember last August, because when I went to Derby I was among the “toffs and swells,” and wore a red suit when the prisoners were taking exercise.

Magistrate: You will have to go again for 14 days.

And so, Tommy welcomed in the new century from his cell at Derby jail.

By January 26th Tommy had been released from jail, had committed the same offence once more, and was back at the Police Court, facing his 85th appearance (according to the Nottingham Journal). This time there was no option of a fine — Tommy was a town nuisance and was given another month in prison.

August 1899: something needs to be done to protect the police

When Sir Herbert Croft, Inspector of Constabulary for the North of England, recently visited the town, he commented on the number of assaults made upon the police in the Ilkeston district and stressed the need for greater protection for the members of the force. He asked Superintendent Daybell to bring this to the notice of the magistrates. Which the superintendent did …. unfortuneately for Patrick Finan.

On the night of August 4th Patrick’s wife, Kate (nee Crow), was arrested and locked up by P.C.Ryan for drunkenness, and Patrick was determined to get revenge. Later in the evening he singled out the P.C. at White Lion Square, walked up behind him, withdrew a poker from his sleeve and brought it down upon the policeman’s head. P.C. Ryan’s helmet saved him from serious injury. Patrick’s defence was that he was drunk, a condition denied by the arresting officer.

Later in court the Superintendent reminded the magistrates of their duty to protect the police. They did this by sentencing Patrick to one month in prison with hard labour. At the same court Kate Finan was sent to jail for a 10 days for being drunk and disorderly, as she wouldn’t pay the fine and costs.

Patrick was born in Roscommon while his wife Kate was born in Ilkeston to Irish parents.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Of course, the anecdotes above give a distorted picture of the Irish contribution to Victorian Ilkeston life. The majority of the town’s Irish folk were law-abiding and hard-working … and leading mundane, boring lives (??!!) so that they do not appear in the pages of the local press.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Let’s visit neighbours Hithersay, Brand and Raynes